Arguing economics and life, missing the DP, Ernie Beck on AJ Brodeur and an old teammate, and more.

Inverse Relationship Between Value and Compensation

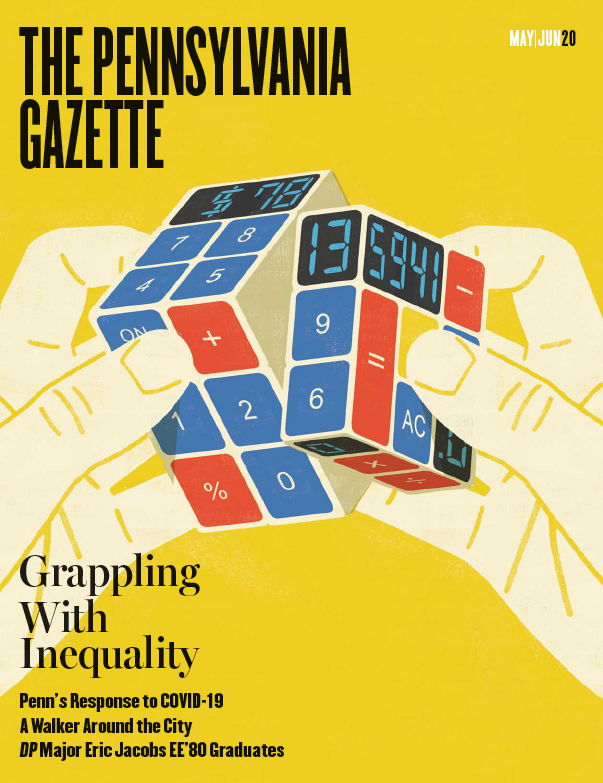

It was gratifying to finally read that someone on the Wharton faculty is focusing on the fundamental inequalities inherent in the US capitalist economy [“Inequality Economics,” May|Jun 2020]. Benjamin Lockwood’s examination of the inverse relationship between the value to society and the amount of compensation paid to working Americans is a long-overdue echo of the research done by Karen Ho more than a decade ago, which she included in her book Liquidated: An Ethnography of Wall Street. There is something fundamentally wrong with a system when the brightest and the best of our graduates are being siphoned off to the financial sector, when society would be far better served if they brought their energy and intellect to bear on the enormous problems that are created by unbridled capitalism (environmental, social, medical, public education, energy, waste management, and the list goes on … ). I hope to read more about Professor Lockwood’s work in future issues of the Gazette.

Helen E. Pettit CW’65 CGS’76, Lambertville, NJ

The Economy We Elected

If Professor Lockwood ran the economy, he’d tax Wall Street out of existence, or at least all of its most successful denizens. It is true that some folks on Wall Street have made billions of dollars. Some, I suppose, were privileged. Some were lucky. Some were just plain smart. I concur that some of these folks probably earn in excess of their marginal contribution to social welfare. That’s true of many of us. But I can assure the professor that for each individual who hits the jackpot there are dozens upon dozens—some equally talented and industrious—who struggle or go broke. That’s not necessarily fair, but that’s what drives our economy forward. In the hope of success, some people are motivated to risk everything against seemingly impossible odds. For whatever reason, some few succeed.

If I ran things, I’d leave Wall Street alone, and I’d tax the following industries out of existence: the cosmetics industry, the “fashion” industry, the firearms industry, the tobacco industry, the corn syrup industry, and, with the professor, the soda pop and bottled water businesses. Talk about industries that waste resources and generate negative externalities. I’d also take a close look at the economics business. Seems to me it hasn’t made even a marginal contribution to anything since Keynes and Hayek.

The great thing about our capitalist economy is that it is not run by me or by the professor or by any single individual or committee exercising arbitrary authority to decide what’s best for everyone else. Instead, it is guided by hundreds of millions of consumers and businesses who daily vote with their dollars for the kind of industries and academic disciplines they want and don’t want. For better or worse, then, the economy we have, like the government we have, is the economy we have elected.

Charles Cranmer WG’82, Haverford, PA

Donors Make Education Affordable

It is ironic that the May|Jun 2020 issue of the Pennsylvania Gazette has a cover story on grappling with inequality and also includes the latest data on annual tuition, room and board, and fees at Penn of $76,826, a 3.9 percent annual increase [“Gazetteer”]. This increase certainly exceeds inflation and the absolute value of it is outside the reach of much of the world’s population. Reference is made to $256 million of financial aid, which puts attendance at Penn within reach for many of the students. It is worth remembering that this education has become more affordable due to the generosity of donors who have funded an endowment that provides these scholarships and other forms of financial aid. The generosity of these donors, the group that is responsible for the inequality referred to in this article, is funding the education of our next generation. Thank you to them!

Paul C. Kelly WG’82, Longmont, CO

Life’s Inequalities

What’s missing from the article is a summary of the worldviews held by Professor Lockwood and his research colleagues. Those worldviews would help me, for one, get a handle on the conclusion that replacement of a bad teacher with an average one raises the future salaries of the kids in the classroom by $250,000 a year.

For that conclusion has no utility. Within any classroom there is an uneven mixture of talents and potentialities—aka students. They were not born equal (except in the sight of their Maker); they will not be treated equally in this life; they will not respond equally to whatever (and unequally) crosses their paths; and they will certainly not be evenly distributed over some income and achievement curve or another.

The inequalities of life—and life’s economics—are most easily understood by taking a hard look at the statue of The Sower who strides the Great Plains from atop the Nebraska State Capitol. Handfuls of seed are unequal in size and composition; where the seeds fall is up to gravity and the breezes of springtime; and how each seed fares after that is unknowable and unpredictable by mere man—let alone a teacher.

Better to ruminate on how to teach individuals to understand and use whatever The Sower’s broadcast brought to them than to fool around with more ways to tax individuals’ monies and properties for whatever government employees think.

Stu Mahlin WG’65, Cincinnati

Adult in the Room

The saga of Eric Jacobs’ tenure at the Daily Pennsylvanian was, indeed, “a marriage made in heaven” [“Paper Man,” May|Jun 2020]. The paper needed “an adult in the room,” who brought organizational and foresight expertise to a very popular and—in some cases—challenging campus publication. The paper had very difficult missions: (1) to publish daily; and (2) to “tell it like it is.” I’m familiar with this yin and yang, having been the editor in chief of the Pennsylvania News, the women’s newspaper, during the early 1960s. Jacobs’ influence on the DP becoming independent and “going digital” is to be highly commended.

Jacqueline Zahn Nicholson W’62, Atlanta, GA

Back to the DP, Briefly

Tommy Leonardi C’89, who photographed “Paper Man,” emailed this after the shoot, and later agreed to let us run it here.—Ed.

On the way to photograph Eric Jacobs, I experienced the freakish and disorienting sight of a near-empty campus on a sunny March afternoon. Having been at Penn as a student and a photographer consistently for almost four decades, I’ve developed an intuitive visual rhythm of the academic seasons. I know what the campus is supposed to look like just by the sun angle at any given moment. When I say “look like,” I also mean “feel like.” There is a completely predictable ebb and flow of energy—marvelous energy—at Penn. And I’ve fed off that energy for almost four decades. The emptiness I experienced this time felt so weird—and wrong.

I then walked up the stairs to the DP offices. Halfway there, I realized that I hadn’t trudged up those stairs while carrying photo gear since 1989. Before I had graduated, I had been (and still am) the most prolific photographer in the history of the DP. The DP is where my Penn photography life started. It was the place where not only did I learn photography, but where I learned how to be a professional photographer. At the DP, I quickly learned to be creative on demand, not only when I felt inspired.

And there I was again, inside the stairwell leading to the place that had shaped my career—on the day it felt as if it was suddenly gone.

I felt disoriented until I entered the DP offices. There was EJ! He smiled at me through the glass wall in his private office. He, of course, was a fixture at the DP when I was there. And he still had that same “EJ way” about him, too. You know how some people change—really change—when they get older? EJ hadn’t. Same person, same energy.

The familiarity of seeing EJ at this suddenly uncertain time was like a magnet. I walked quickly toward him and, being emotional, I approached to hug him as he stepped toward me, too. Two feet away, we both stopped in our tracks. We could not hug. Two Penn alumni with a deep connection during a scary time weren’t allowed to hug. Social distancing was the call of the day.

It took at least an hour before we even tried to set up the shoot. That’s because I quickly realized how “off” the Penn world had become to EJ as well. For over four decades, EJ had also lived off the Penn energy, but through a different, figurative lens. He knew when the students would arrive at the DP. It was entirely predictable. But it now was mid-March and the students were not there.

Instead, we talked about, well, everything. First the virus, then the current state of the DP, and then the memories. Through much of the conversation, we toured the offices, discussing the changes: the walls that were removed and added, and the people who used to work in each space.

That’s when I started to feel a bit normal again. Then we set up the shoot. I felt wonderfully light. I was able to “lose myself” in the shoot and the world was right again.

Just after the shoot, however, I looked at my phone. It had blown up with alerts of the latest coronavirus news. Reality came right back.

After I broke down my equipment, I was chatting a bit with EJ and another DP employee. I said, “I know that the idea of a ‘safe zone’ on campus is sometimes mocked. But if I could be back here at the DP in the late ’80s until this crisis ended, I would. Since that’s not possible, I guess I’ll have to go home.”

Tommy Leonardi C’89, Philadelphia

Winner, All-Time Record for Sportsmanship

I just received the May|Jun 2020 edition of the Pennsylvania Gazette and was happily surprised. Normally, as a 90-year-old graduate from Penn, I look first at the obituaries to see if any of my old classmates had recently passed away. Then, when I turned back to the sports section, there was a picture of me congratulating AJ Brodeur, now the all-time leading scorer in Penn’s varsity basketball history.

I was at the Palestra the night when he broke my record, having been invited to the game by Steve Donahue, who has done a great job in his years as head coach. The smile on my face is sincere for I had the scoring record long enough (67 years). AJ certainly deserves the honor for he is a well-rounded basketball player as not only a scorer but great as a passer and on defense.

Then, to top it off, I turned to an earlier page of the Gazette to the story “Those Woodstock Summers” [“Elsewhere”] and found it was written by Nick Lyons W’53, an old basketball teammate at Penn. He played on the freshman basketball team with me in 1949. Nicky was a tough little guard on the team. We could not play varsity because of the Ivy League rule in those days that freshmen could not play varsity but should concentrate on their studies first. We played our games at Hutchinson Gym, next door to the Palestra, against other freshman Ivy League teams because of the rule. Nicky also made the varsity, and we both played three years on the varsity basketball team. And we had a great coach, Howie Dallmar.

My scoring record was for three years, not four. Some consolation! However, congratulations again to AJ Brodeur.

Ernie Beck W’53, West Chester, PA

Beautifully Written

Thank you to Nick Lyons for “Those Woodstock Summers,” a beautifully written letter to his younger self and beloved wife. I can’t wait to read Mr. Lyons’s forthcoming memoir, Fire in the Straw: Notes on Inventing a Life.

Irene Jacobsen Gr’02, Urbana, IL

Outstanding Teachers, Different Eras

I enjoyed “Mind Traveler,” the short article on Renée Fox [“Gazetteer,” May|Jun 2020]. It brought back memories of my days at the medical school and Wharton grad in the latter ’60s and earliest ’70s when I first learned of her concept of the “training for detached concern” of medical students. This sociological concept that physicians needed to be able to blend a degree of emotional detachment with ongoing concern for their patients in order to prove effective resonated for me when I first became aware of it. I think it correlates nicely with the earlier stated concept of medical pioneer Sir William Osler, who taught at Penn in the 1880s, of equanimity in balancing a vigorous effort on behalf of patients, while realizing that eventual outcomes in patient care were often beyond the physician’s control and must be accepted for good or ill. Both have been outstanding teachers at the University in their respective eras. It is good to know that Renée Fox remains a vigorous “mind traveler,” although more restricted than earlier in her geographic journeys.

Peter L. Andrus M’70 WG’76, Lakeway, TX

Lasting Lessons from a Super Teacher

Henry J. Abraham [“Obituaries,” May|Jun 2020] was at the top of the super teachers I was blessed with at Wharton. He taught political science that stayed with me over the many years since I sat in his classroom in Logan Hall. Recently I came across an Abraham classroom video published by the University of Virginia, where he taught after Penn. There he was—all over again—endowing an entirely new student generation. It is teaching like Abraham’s that makes Penn-Wharton such a jewel in the crown of collegiate education. Henry lives on in the lives he enriched.

Walter L. Zweifler W’58, New York

Coming Through in Trying Times

Your May|Jun Gazette was amazing, showing once again how Penn comes through in trying times. Of course you cannot find mention of the 1918 influenza in your archives [“From the Editor”], because Philadelphia was the very epicenter of myopic indifference to the spread of this disease, as described in many accounts of the time. Similar misjudgments are occurring today, but Penn, as you know, will not stand by quietly. Thank you.

Ken Klein C’67, St. Paul, MN

Earth Day Memory

Your 50th year recollections of Earth Day 1970 [“Old Penn,” May|Jun 2020] brought back the memory of my own involvement on that day, which was not in Fairmount Park. I was in a party of about 50 who were sitting in at Philadelphia City Hall, bearing an eight-foot diameter version of an Earth Day button. I have been proudly donning my (smaller) version of that button every Earth Day since then.

Bill Tracy WG’75, Denver

Home Run

Nice job on your Mar|Apr 2020 issue. I read and enjoyed all four feature articles, a real home run.

Bill Mosteller C’71, Fairfax, VA

Decrease in Quality?

Overall, I enjoy reading many of the articles in the Gazette and, unlike some readers, am not upset by the, often liberal, views expressed by many authors. But the Mar|Apr 2020 edition, if you’ll pardon the expression, really takes the cake!

First, in “A World Without Prisons,” we have to put up with the claptrap of Angela Davis [“Gazetteer”]. She has been sounding off about everything that upsets her since the ’60s but has never amounted to much of anything other than noise. Really, does the Gazette have to make room for one of her diatribes?

Then, when I saw the cover, with the words “The End They Chose,” I thought I might be seeing a serious article or articles on end-of-life issues. Instead what we have is somewhat of a sob story about a new professor and her partner who (sad to say) passed away from cancer [“Finding Life in Death”].

I hope that we are not seeing a decrease in quality of this generally fine publication.

Joel Ackerman C’62, Jerusalem, Israel

What the Data Show

If Joanne Gover Yoshida [“Letters,” May|Jun 2020] has evidence to support her position that “there is a God who controls the climate … keeping it … preciously balanced,” please will she present the evidence for us to review? The data that I have seen so far are more consistent with the Christian theory (2 Peter 3:5-10), that God has again (cf. Genesis 6:11-13) lost patience with His creation and is burning up the world “with fervent heat.”

Henry Blanco White L’02, Collegeville, PA

Science and Prayer

Ms. Yoshida: How are you so certain it’s a He and not a She? Do you have any proof? You don’t take any science into consideration in the state of our climate. I am pretty certain that your studies at the Wharton School or the architecture program did not teach you your monotheist beliefs. Please keep the people suffering with the COVID-19 in your prayers. That would include my 88-year-old father in a nursing home. Appearance of your letter shows the Gazette’s balance in including a variety of opinions.

Vicki Rothbardt Oswald GEd’89, Wyncote, PA

On Climate, Influence What We Can

Regarding Rachel Frankford’s request to the Gazette to not give “climate hoaxers” a platform to express “their lies and conspiracy theories” [“Letters,” May|Jun 2020], she should be reminded about the First Amendment to the Constitution, which guarantees freedom of expression to all. Relative to those who believe in the anthropogenic influence on the Earth’s climate, carbon emissions can certainly be recognized as adding to climate change, but there are other greater factors which must be considered. Ten thousand years ago there was an Ice Age that came about with zero influence from man. (It is hard to fathom, but at one time there was estimated to be a mile of ice covering what is now New York City.) What followed that Ice Age and continues to this day is what is referred to as an interglacial (warming) period, which is a natural cyclical occurrence involving nothing anthropogenic. Approximately 141,000 years ago, another glacial period came to an end because of changes in the obliquity, or tilt, of the Earth. The smallest amount of tilt exerts a massive influence on climate, something the Inuits, who are very nature oriented, are well aware of. In the big picture, there are some influences on climate about which we can do something—specifically, carbon emissions—but there are other influences caused by our sun that are far more consequential over which we have no influence. Using our intelligence and vast resources to do things like planting one billion trees that sequester carbon dioxide will help to keep climate change at bay.

Sydney Waud C’63, New York

There, Pick a Side

John Silliman complains [“Letters,” Mar|Apr 2020], when referring to the climate crisis articles in the Gazette [“The New Climate Advocates,” Jan|Feb 2020], that there should be “two sides to every scientific or even political issue,” and lately the “right’s side of climate change is totally missing.”

That’s because when it comes to the actual science of anthropogenic greenhouse gases warming the planet and the urgency of reversing course, the “right’s side”—there is no consensus, not to worry, conditions haven’t “changed that much”—is dead wrong.

But since Mr. Silliman wants alternatives, here are two sides to choose from: side one—the people of the planet can work together with unprecedented determination and resolve to require the rapid transition to carbon neutrality through 100 percent green energy and sustainable practices. Only then do we stand a fighting chance of slowing, and even reversing, the impending climate catastrophe.

Or, side two—we can take the right wing approach, allow the powerful energy, industrial, and agricultural giants to continue their exploitive and profit-mongering practices at the expense of human health and the future of our planet. Meanwhile, the rest of humanity sits back helplessly as we pass every possible tipping point; and the world’s climate, ecosystems, habitats, plant and animal communities, ice sheets, coastal cities, and civilizations continue the gradual and irreversible death march towards destruction.

There, pick a side.

Ricardo Hinkle C’86 EAS’86, New York

Wanted: Fewer Words, More Action From “Climate Scientists”

Unfortunately, “The New Climate Advocates” was all hot air. While the Penn motto is Leges Sine Moribus Vanae, these writers should adopt Sermo Sine Actum Moribus Vanae. Words without actions are in vain. All pseudo-science and studies.

Like all “climate scientists,” they drive cars, take Uber, whisk to global symposiums, drink lattes in takeaway cups, run air conditioners in summer and heat to 72 degrees F in winter.

To paraphrase St. Paul, judgement will be by our faith and actions. Are they planting trees on the weekend? Cleaning the Schuylkill River of litter on Sundays? Have a pebble yard instead of grass for their children? Doubt it. Probably reading the New York Times and dismissing deniers

My American companies I started 30 years ago convert acid rain from electric power plants into synthetic gypsum to produce 3,000,000 tons annually for wallboard and cement substitution. Our investment, our risk, our time, our practical ideas. No government handouts, coercion or mandates … just citizen action. Another 3,000,000 tons is recovered from steel plants for reuse, and recovered copper slag and iron ore slag serve as raw material replacements into cement to reduce their carbon footprint. All practical applications without infringing on the rights or habits of others.

Currently I am a rancher in New Zealand, where we converted 1,700 acres from sheep and beef into a Radiata pine plantation for both carbon sequestration and wood to eventually replace cement and steel. Converting our home sheep station into a more environmental operation with less inputs was more challenging. In 2017, 2018, and 2019, we annually planted 3,000 native plants by hand to reduce excess water flow off the land and to regenerate marginal land into native bush. That was accomplished by planting for two hours every day after dinner for months. No government subsidies, no tax rebates, no assistance. Direct action. No handwringing or beseeching governments to intervene on private land and diminish or expropriate the rights of others

When I was raised by my parents (Charles P. Colgan C’49) and rowed at Penn with crew coach Ted A. Nash, the clear and unequivocal exhortation was that actions speak louder than words. Just think of all the carbon that would be saved if those confronting climate change actually did something physical about it. Why circumnavigate the globe for conferences when Zoom can be carbon neutral?

Sean P. Colgan C ’77, Napier, New Zealand

Revive Passenger Rail Service

This refers to the story “Flight Risk” in “The New Climate Advocates.”

Hoorah for Dan Hopkins for refusing to fly from Philadelphia to San Francisco for a conference. Professor Hopkins calculates the CO2 pollution generated by every gallon of jet fuel burned.

Several decades ago, Professor Hopkins could have traveled at relatively high speed from Philadelphia to San Francisco by rail (though not as fast as by air). If we had that level or faster service today he could enjoy traveling to San Francisco by train. Train time is brain time. With today’s computers, pads, and smartphones, he would have no problem working and communicating. And he would enjoy beautiful country scenery and the life and scenes of the cities passed through. You can’t see much at 30,000+ feet.

Professor Ryerson (also quoted in the article) recognizes the problem and suggests several means of avoiding the pollution that air travel causes, and that is good. But the article failed to mention and encourage a real solution to much of the increasing pollution of air travel.

That solution is passenger rail service, particularly high-speed rail, which every advanced country, and many not-so-advanced countries, already have. The United States has relatively few miles of high-speed passenger rail, in the Northeast Corridor. But it’s not really high-speed; not like that in other countries.

Why is the US the only advanced country without adequate passenger rail transportation? A little history: the Civil Aeronautics Board and the Federal Aviation Administration—unlike the Interstate Commerce Commission, which regulated rail (and bus) transportation—highly promoted air travel, in addition to regulating it, and the federal government still does. Added to this, the Eisenhower administration brought into existence the Interstate Highway System, which promoted and greatly improved auto and bus transportation. But improvement of passenger rail, the third mode of public transportation, was not included.

Through the mid-20th century, the railroads provided excellent passenger trains, which improved their image for freight, as well as passenger. But instead of considering passenger service as a by-product, running on rails that were there for freight anyway, they considered passenger service a burden. (Of course, the speedy trains needed upgraded tracks.). So passenger service was turned over to Amtrak in 1971, but Amtrak was, and still is, a mere skeleton of the former passenger service.

President Trump would like to curtail Amtrak even further. If Joe Biden, who appreciates passenger rail service, succeeds Trump in 2021, perhaps he will become the Eisenhower of passenger rail, and promote a comprehensive passenger rail system.

Let Penn, which recognizes the environmental damage of air transportation, be in the vanguard of promoting passenger rail service.

Theodore Otto Haas C’56, Haverford, PA

Marcus Aurelius on Change

Debate rages over the validity of climate change. Perhaps the words of Marcus Aurelius, Rome’s philosopher-emperor (b. 121 AD, ruling 161–180 AD), may place the issue in a more agreeable context.

Historians hold Marcus a man of reason, keen observation, and high personal discipline, with much appreciation for life and the universe. These writings came during encampment with the Roman Army north of the Danube, during the Quadi war. Comments are from the Penguin Classics edition of Meditations.

Among the truths you will do well to contemplate most frequently—all visible objects change in a moment, and will be no more. The whole universe is change (p. 64);

Observe how all things are continually being born of change; teach yourself to see that Nature’s highest happiness lies in changing the things that are, and forming new things after their kind. Whatever is, is … the seed of what is to emerge from it (p. 72);

To be in process of change is not an evil, any more than to be the product of change is a good (p. 73);

One thing hastens into being, another hastens out of it. … Change is forever renewing the fabric of the universe. In such a running river, in which there is no firm foothold, what is there for … man to value among all the many things that are racing past? Justice, kindness, belief in God, appreciating one’s place in the ever-changing world (p. 93);

Only a little while, and Nature, the great disposer, will change everything you see, and out of their substance will make fresh things … to the perpetual renewing of the world (p. 109);

Soon enough everything that now meets your eye, together with all those in whom is now the breath of life, must be no more. For all things are born to change and pass away and perish, that others in their turn may come to be (p. 183, italics added);

For a life that is sound and secure … put your whole heart into doing what is just, and speaking what is true; … know the joy of life by piling good deed on good deed until no rift or cranny appears between them (p. 186).

Richard Masella D’73, Boynton Beach, FL