As a nursing professor, Kimberly Acquaviva teaches students about end-of-life issues and hospice and palliative care. When her wife, also a leading hospice expert, was diagnosed with a fatal type of cancer, Acquaviva turned their home into a virtual classroom, inviting anyone on the internet to witness the intimate details of dying—while making a case for more varied and inclusive options for the terminally ill.

By Dave Zeitlin | Photo by Christopher Tyree

In the months before @Kathy_Brandt died, she liked to joke that she would make her presence known after she died by controlling the wind in our backyard. (Weird, I know). Now the sound of wind chimes makes me wistful.

—@kimacquaviva, January 12, 2020

There’s a painting in Kimberly Acquaviva C’94 SW’95 Gr’00’s house that she recently made. It hangs above the sofa where her wife, Kathy Brandt, spent some of her final weeks alive, beneath the skylight that Kim and Kathy would dreamily gaze through as they thought about the life they shared and when it would end. It consists of just four words, in big block letters, painted on a white background. A conversation starter, certainly, for anybody who’s since passed through the Charlottesville, Virginia home to offer their condolences. The words: Viagra Melts The Snow.

Kim created the painting not long after Kathy, her wife and partner of 18 years, died on August 4. Kathy was 54 and had been diagnosed with ovarian clear cell carcinoma a little more than six months before her death. Near the end, as her liver and kidneys shut down and medical marijuana coursed through her blood to alleviate the pain, Kathy began to spew things out that made Kim laugh through her tears. Like asking if Kim’s non-existent husband had a good job. And insisting that “we have to get rid of Pennsylvania—have to.” And the entire day that she was absolutely sure that Viagra could magically melt snow so children could play outside. “There’s humor,” Kim says, “in even the most horrible moments.”

The painting hangs in her living room as a reminder of that. More reminders can be found on the internet, whether on Kim’s Twitter profile (@kimacquaviva), her Facebook page, or the GoFundMe account set up by a friend to defray Kathy’s healthcare costs. It was there that Kim (and sometimes Kathy) documented, in intimate, painful, and often amusing detail, why Kathy decided to forego chemotherapy and later comprehensive hospice care (two decisions that surprised colleagues and cyber strangers alike), how to be a caregiver for someone at the end of life (with only modest assistance from a palliative care physician), and how to navigate the painful and profound moments that accompany dying and grief.

Few people could have been better qualified for such a mission. Kathy was a hospice industry leader who, most recently, had been tasked with writing and editing the latest edition of the National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care’s Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. Kim is a licensed social worker and nursing professor, first at George Washington University and now at the University of Virginia, who authored the 2017 book LGBTQ-Inclusive Hospice and Palliative Care: A Practical Guide to Transforming Professional Practice.

Already “beloved” by the palliative care community, according to Amy Berman, a senior program officer with the John A. Hartford Foundation (which is dedicated to improving the care of older adults), “Kim and Kathy making the choice to publicly share what they’re going through was a very brave act. But it was more than a brave act. It was a chance to really help inform people who may be going through these experiences.” Berman, who has been living with metastatic breast cancer for nine years, notes that palliative care—which aims to optimize quality of life and mitigate suffering for the seriously ill—is not well understood by the public and that caregiving information for non-professionals isn’t readily available. That’s why she too has been a vocal proponent of palliative care, and appreciated the honesty of Kim and Kathy’s public project.

“It was so much more than the illness,” Berman says. “It was about their relationship. It was about how they go through grieving, how they handle life, how they handle the challenges related to caregiving. It was such a profound gift to the world.”

The longest conversation I had today was with the person who delivered my groceries. The involuntary solitude of widowhood is too much introverting even for Big Ol’ Introvert me.

—@kimacquaviva, October 5, 2019

On the early January day I visit Kim at the University of Virginia, a steady snow falls on the picturesque Charlottesville campus. (It’s doubtful anyone has tried to use Viagra to melt it.) Students have yet to return from their winter breaks and some faculty members have begun to plot their escapes home. “We don’t do well in the snow here,” someone says. Others explain they have to get to the “other side of the mountain” before the roads get too slippery for their cars to climb. “I’m not sure where the mountain is,” Kim, still a Charlottesville newbie, tells me with a smile. Armed with a Jeep and a fierce devotion to her job, she probably wouldn’t have left early even in a blizzard. She enjoys the company of colleagues she calls “the greatest,” in part due to the warm welcome she received when she started there only days after Kathy died. “I’ll never quit UVA because of how they treated me,” she says. “Like, I will work here until I die.”

Kim wasn’t looking for a new job when, in early 2018, she came to UVA to give a presentation during an LGBTQ Health symposium. She was happy at George Washington, where she had been teaching for 15 years. But the invitation, she later learned, was part of a recruiting effort to expand the faculty beyond nurses. After returning for another campus visit with Kathy and their teenaged son Greyson later that year—and having her concerns assuaged about moving to a state where at the time someone could be legally fired for being gay—she accepted an endowed professorship, and the family began preparations to move from Washington, DC, to Charlottesville.

A few months later, on January 29, 2019—Kim’s birthday—Kathy was diagnosed with cancer. Her illness was terminal, their world turned upside down. Racked by sadness and stress, Kim wanted to back out of her UVA contract. But when Kathy asked if she was excited about the position, Kim responded, “Yeah, it’s my dream job.” Kathy, who always wanted to have a quieter life away from the city anyway, told her, “Then you’ve got to do it.”

Less than a year later, Kim is sitting in a large room inside McLeod Hall, where UVA Nursing is housed. She’s there for a start-of-the-semester meeting in which fellow faculty members, divided into small groups, are debating guidelines put forth by the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN). Against a drab tan-walled backdrop, Kim’s bright red sweater and pink mug make her stand out. So, too, do her contributions to the discussion. At one point, she playfully jabs the AACN for not using Oxford commas. (She’s passionate about punctuation; one day after Kathy died, she posted a photo of an urn along with this tweet: “I’m taking a brief break from crying to judge the Virginia Cremation Society harshly for their rejection of the #oxfordcomma.” She also hosts the grammatically named Em Dash Podcast, billed as “the healthcare podcast that gives you pause.”) At another, she says, “I thought nurses are fiery advocates,” claiming that the paper in front of her makes it sound like they should simply be “rules followers.” Later, she admits that she might “skew a little too radical”—though her colleagues, whom she says are “very social justice focused” like her, mostly nod in agreement to everything she says.

Kim has a different background than most of the people in that room. Describing herself as an “activist academic,” she believes she’s both the only out lesbian faculty member at UVA Nursing and the school’s only social worker serving as a tenured professor. It’s a career arc she wouldn’t have predicted when she first arrived at Penn in 1991, intent on studying art history and then going to law school. But her dreams of being an art lawyer faded during a tedious internship at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where she spent her time “editing a book on Dutch tiles in a closet office.” Deciding she needed a “more people-oriented major,” she shifted to sociology as an undergraduate, and then remained at the University continuously for almost 10 years, getting a master’s in social work and a PhD in human sexuality, with a focus on homeless women and HIV/AIDS. “Penn was interesting because I was trying to figure out who I was,” she says, calling it the “best decision of my life” to attend the University.

Kim was still working on her dissertation when she followed a girlfriend to Florida and began to work at Suncoast Hospice. There she met Kathy, who served as the hospice’s head of outreach—and had to deal with Kim pestering her about what her newly created job as a research director should entail. “I drove her nuts,” Kim says. “She made a duct tape line on the entrance to her cubicle office for me not to cross because I was bothering her so much.” Soon enough, Kim (who had since broken up with her previous girlfriend) broke past that line and the two became friends. Later, they started dating. When Kathy was recruited for a senior-level position at the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization outside of DC, they packed their bags together for the nation’s capital, where Kim landed a job at George Washington, first as a visiting faculty member and then as a tenured professor.

Life in academia has suited her well ever since. At UVA, she teaches health policy to undergraduate and graduate students, trying to “weave LGBT inclusion, social justice, and racial equity into every class.” And beyond the classroom, too. Shortly after the morning meeting ends, I follow Kim to a slideshow presentation she’s giving entitled: “LGBTQ-Inclusive Palliative Care: A Caregiver’s Perspective.” Right off the bat, she asks the UVA nurses and doctors in the room if they want a technical presentation or a more personal one. Every hand goes up for the latter.

So she tells them about Kathy.

Kathy and Greyson are taking disco naps. Listening to the two of them breathing softly, my heart sings. Then I remember that one of these gentle snores will fall silent soon and my breath catches in my throat. Still, there is joy in the now.

—@kimacquaviva, April 26, 2019

Although they’d eventually be dubbed a “palliative care power couple,” Kim and Kathy weren’t always as open about their relationships and sexualities.

As an adolescent in a conservative, religious family in Irving, Texas, Kim tried to repress her attraction to girls. It became too much while attending a private all-girls high school. At 15, she wrote a few notes, stuffed a bunch of Tylenol and Codeine into her mouth, and waited to die. School officials found her in the bathroom, not completely unconscious, and called her parents. Her parents took her to a doctor and later to a single counseling appointment but, to Kim’s dismay, not much else was said about the suicide attempt. It wasn’t until many years later, after Kim fled Texas for Pennsylvania—first to Beaver College (now Arcadia University), and then on to Penn as a transfer student—that she came out to her parents. Her mom’s response still baffles her. “She started to cry and said, ‘I never taught you how to make a good vinaigrette,’” Kim recalls. But thereafter their relationship grew stronger.

After her mother was diagnosed with a cancer similar to the type that would later befall Kathy, Kim returned from Philly to Texas to act as her healthcare surrogate. The experience would prove formative. For one thing, Kim realized that sometimes family members are better equipped than clinicians to answer more private questions (though she was still a “little mortified” when her mom asked her about vaginal dryness as a side effect of chemotherapy, after the oncologist had shied away from the topic). Secondly, she began to question the point of chemotherapy for the terminally ill. Her mom lived four years with stage IV cancer and “felt like crap” the whole time. And finally, she grew convinced that battle metaphors are the wrong way to think about cancer. Her dad, a Vietnam vet, immediately drew up a strategy to beat the cancer, even though Kim knew that wouldn’t be possible. “When we say things like, ‘You’re going to fight this, you’re going to beat this,’ it sets people up for failure,” she says. “And for many cancers, it isn’t an even match. No amount of will is going to cure a cancer that’s incurable.” Instead, she learned that hope can be found in little moments of perseverance and humor along the way. One of the last things her mom said before dying at 52, as she listened to family members talking about her by her bedside as if she wasn’t there, was: “You know, I’m not dead yet.”

Kim would draw on all of these lessons when caring for Kathy. But that wasn’t yet a flicker in her mind when the two were becoming friends in that Florida hospice. Her biggest concern then was convincing Kathy—who was seven years older—to finally come out to her own parents so they wouldn’t have to hide that they were dating. She also wondered how their relationship would work with the young child Kim had adopted with her former partner, before an ugly breakup left her temporarily as a single mother. Kathy had “never wanted to be a parent,” Kim says. “She always thought she would be a bad mom.” She was wrong. Kathy fell in love with Greyson, the two soon bonding through sports, comic books, and action movies. “Her skills were the perfect complement to mine,” Kim says. “My son likes to say that she was the fun mom.”

Kim’s father, Phil, also forged a strong connection with Kathy. Even though Kim says it was initially hard for him to wrap his head around his daughter’s sexuality, he adored Kathy—and her dry humor—from the start. “Don’t mess it up with this one,” he’d tell Kim often. Kim knew the feeling was mutual but was still surprised when Kathy asked for Phil to be with her in Charlottesville during their move while Kim stayed in DC to direct the packers. Phil, who doesn’t like airplanes, made the two-day drive from Texas to oblige, and the two set up lawn chairs in an empty house to wait for furniture to be delivered.

Kim, Kathy, and Greyson loved their new neighborhood and home from the start, but as Kathy wrote on the GoFundMe page (aptly named “For Quality of Life at the End of Life”),“nothing dampens one’s home-buying enthusiasm quite like realizing this is the house in which your spouse is going to die over the summer.” By the time they moved in, last June, Kathy didn’t have enough energy to navigate the stairs in front of the house or to get in the car, so they rarely went out in Charlottesville. She mostly laid on the sofa, binge-watching The West Wing or Grace and Frankie, but even keeping track of her favorite TV shows proved challenging as her condition deteriorated. In a post she wrote in May, Kim lamented: “I want to host Thanksgiving with Kathy and have a house full of family and a basket full of crescent rolls I burned because I was too busy laughing to pay attention to the oven timer. I want to sit next to Kathy on Christmas morning wearing dorky matching pajamas and opening stockings with Greyson. I want the house to be an envelope Kathy, Grey, and I stuff full of memories over the next twenty years. Knowing Kathy won’t be with us a few months from now to stuff that envelope makes my heart hurt.”

In her own posts, Kathy admitted to feelings of existential distress and sadness, writing, “There’s no roadmap for people like me who have a defined time when they will cease to exist.” But with Kim, she was determined to try to create one with the little time she had. “We wanted to show people the good and the bad because we didn’t know what it was going to look like,” Kim says of their decision to document what palliative care, instead of chemotherapy, looks like. “It’s shitty to find out you’re dying. But it’s less shitty if you and your spouse both work in this field and are open to talking about it publicly so maybe other people can learn something.”

Every day Kathy looks less alive when she sleeps. It feels like the universe is preparing us for her death by giving us daily dress rehearsals. BTW, dying is “slow and boring,” according to my always-on-the-go wife.

—@kimacquaviva, July 20, 2019

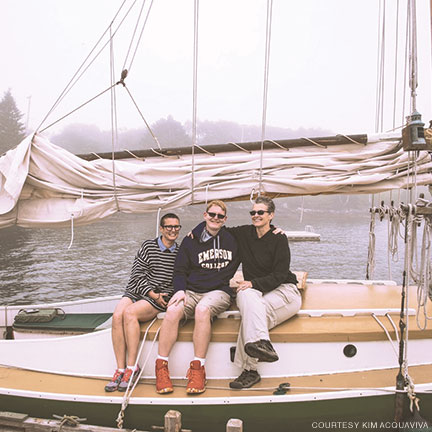

On their way to Boston to move Greyson into Emerson College in August 2018, Kathy fainted. She didn’t leave the hotel room for three days, vomiting most of the time, while Kim hauled boxes into a dorm room and gently teased her about it. “She was kind of a big baby when she was sick,” Kim laughs. “In the earlier years when we were together, I was like, ‘I swear, when you get old, I’m not going to be able to handle it,’ because she was a bit of a drama queen.” (In hindsight, Kim admits she was “not the best wife about it,” though Kathy’s disdain for feeling under the weather and going to the hospital would end up influencing their decision to forego chemotherapy and hospice.) When Kathy fainted again a few months later, Kim knew something was wrong. They hurried to get a medical scan done. The results were not good.

A day after the cancer diagnosis, Kim sent an email to an emergency medicine doctor at George Washington that she knew, thanking him for how they were treated and asking for an urgent referral to Sibley Memorial Hospital oncologist Mildred Chernofksy. “Kathy and I are both hospice folks—we know what all this means and it’s bad,” Kim continued in the email. “Kathy’s a realist … if this is Stage III or worse, she only wants to do surgery followed by aggressive palliative care.”

Though they were always clear about their plans to avoid chemotherapy or radiation, it still stunned a lot of people when they followed through. After Chernofsky performed the February surgery to try to remove as much of the cancer as possible, Kim says the oncologist told her she had never had a patient refuse chemo before and that she was crushed by Kathy’s decision. In a National Comprehensive Cancer Network poll of nearly 150,000 ovarian cancer patients from January 1998 to December 2011, fewer than two percent opted out of chemo. But Kathy had a rare form of it and, at stage III, it had already spread to her abdomen and liver. “It wasn’t a curable thing,” Kim says. Maybe, with chemo, Kathy could have lived an additional six months, which Kim realizes is something most people Kathy’s age might take. But given the side effects, “that wasn’t really a great deal for Kathy and I.” Kathy was steadfast, and Kim was supportive. Support often morphed into combat.

When a family member sent Kathy a message that said, “I know you think you’re too weak for chemotherapy, but you have to fight this,” Kim was furious. And don’t get her started about the contractor renovating their house in DC who left them a book about carrots curing cancer. Or the person who asked why Kim hadn’t seen the signs of Kathy’s cancer sooner, given that her mom had had the same disease. “Everything seems obvious in hindsight,” Kim retorted online. “For example, I just realized you have the emotional intelligence of a gym sock.” In another post, Kim wrote, “If y’all use war imagery in reference to her cancer—e.g. fight, battle, win, lose, etc.—I’ll punch you in the throat. Lovingly and in a super-Quaker way, obviously, but it’ll still hurt.”

Kim was less contentious, though equally unflinching, in explaining the couple’s choice to decline hospice care, which generally brings together nurses, doctors, social workers, and spiritual advisors to provide comfort to a dying patient at either the patient’s house or a facility such as a nursing home, hospital, or a hospice center. As the disease progressed, and Kim grew exhausted changing her wife’s diapers and turning her in the bed so she didn’t get pressure sores, many well-meaning people reached out to ask why she didn’t seek assistance from a professional. Kim responded in a post that her personal hands-on care constituted “intimate acts of love that I enjoy doing for Kathy,” adding: “We’re introverts and we have crazy dogs who bark at strangers and we’d rather not be bothered by regulatory-required nurse visits we don’t need.” But there was a bigger reason. “I don’t want hospice,” Kim continued, “because I know what good hospice care is supposed to look like and I don’t want to spend these last weeks with Kathy feeling disappointed, frustrated, or enraged by less-than-optimal care. Kathy spent her entire career advocating for exceptional end-of-life care and so have I. Nothing would increase her suffering (or mine) more than getting shitty hospice care. And shitty hospice care is a very real possibility, especially for us as a lesbian couple.”

As Kim found while researching her book, such bias might include a healthcare worker directing a question to a biological family member instead of the patient’s partner, or not calling a transgender patient by their preferred pronoun. In Kim and Kathy’s case, it mostly boiled down to nearby hospices lacking an LGBTQ-inclusive non-discrimination statement (meaning it didn’t include “gender identity” or “sexual orientation” next to “gender,” “race,” “religion,” etc.). “If you won’t take the time to change a few words in a statement, LGBTQ people have no reason to believe you’ll do a good job giving care,” Kim says.

Leslie Blackhall—Kathy’s palliative care doctor at UVA—had some concerns about managing Kathy’s care without hospice intervention. But having come of age in her profession during the 1980s AIDS crisis, she understood their position. She says the first hospice patient she ever took care of was told by a nurse that he was going to hell because he was gay. “It made me hesitate as to which hospice I can send people to,” Blackhall says. Given that hospice workers are tasked with meeting their patients’ emotional and spiritual needs, it’s especially a concern for LGBTQ baby boomers, who might be estranged from relatives and are used to hiding their identity out of fear of such religious judgments.

“If you think about end-of-life care, people only die once,” Kim says. “You really only have one chance to get that experience right. And for many of us who are LGBTQ, we’ve had a lot of bad experiences with healthcare providers.”

Last night in our house after we finally roused @Kathy_Brandt:

G: Mom, you SCARED us! We couldn’t wake you up. I even asked “are

you dead?!”

K, groggily: Did I say yes?

—@kimacquaviva, July 3, 2019

On the morning of August 4, Kim woke up at around 3:30 a.m. when she noticed Kathy’s breathing change. She talked softly to her wife about ocean waves and cobalt blue sea glass. At 4:51 a.m., Kathy took her last breath. Kim tucked her in, took a shower, and then made cinnamon rolls. She’s still not sure why—perhaps for some sense of normalcy.

Kim then called Leslie Blackhall, who had bonded with the family, to come to the house to pronounce Kathy dead. “It was singularly the best palliative care intervention ever,” Kim says, calling it a “real gift” to not have sirens or lights outside the house (it wasn’t an emergency, after all). “It was one of the more peaceful scenes I’ve ever walked into at the end of life,” Blackhall says. “There was grief, but the grief had been this ongoing process.” Kim and Greyson then fulfilled a promise they had made to Kathy and went out to eat, crying over their beet salad and burger.

Because they’d been so public on social media, the outpouring of support came immediately. After Kim tweeted that Kathy had died, one Twitter user replied, “I had a feeling when I woke today. What a wonderful testimony to her life you and your son have offered. In sharing you normalized death for so many others. I bow to you.” Another wrote, “Your family has provided us with a thing so precious I don’t think there is a name for it. Thank you from the deepest part of my soul.”

From the start of her social media updates, Kim had been surprised to learn how little people knew about dying. She tried to be as informative as possible. The day before Kathy died, Kim posted a video of the beginnings of her “death rattle”—the distinctive sound caused by the accumulation of fluids in the throat and upper chest. A day before that—and 48 hours after Kathy had last expressed a desire for ice chips or water—she explained in a tweet thread that when someone stops wanting food and water it’s their body “doing its best to die peacefully.” She compared it to a car not needing gas if it’s sitting in a garage, and called it an “act of love to listen to what their loved one’s body is telling them,” even if every instinct you have tells you to make sure your loved one eats and drinks.

Occasionally, someone would express alarm that beaming out intimate information to nearly 6,000 followers seemed exploitative. In response, Kim filmed a video of Kathy saying this was her wish. “She wanted people to see that death is not scary,” Kim says. Since then, Kim has received many more messages from people whose loved ones had also died. At Kathy’s memorial service in Washington, DC, at least one person showed up having only known Kim and Greyson through Twitter. “It’s helpful because you don’t feel like you’re quite as alone,” Kim says. “People have stories to tell, and they don’t get a chance to tell them very often.”

When one distressed parent reached out to her on Twitter with concerns about their child making a conscious choice to stop eating and drinking, Kim made sure to say that having a local hospice involved would be really important. She’s still a believer in hospice but would like to see more situations where people can take care of their loved ones in their homes “with hospice kind of backstage.” She’s also been pleased that some hospices near her have changed their non-discrimination statements to include sexual orientation and gender identity since she publicly raised the issue.

Blackhall, too, believes in hospice “because most people are not Kim” in terms of their caregiving abilities. But in addition to the LGTBQ issues that Kim has raised, which she deems “really vital and a perspective not often heard,” Blackhall hopes to see hospices become more inclusive in other ways. “How do you communicate with patients if they don’t speak English?” she says. “Do you have an understanding of cultural traditions at the end of life, and are you violating them by assuming they’re the same as yours?” Kim often hears clinicians assert that they’re not discriminatory because they treat everyone the same, but to her that means “they’re not open to learning how maybe treating everyone the same means you’re not treating some people the right way. Because not everyone is the same.”

Interestingly, Kathy never wrote or spoke of LGBTQ inclusion until she was dying. And she had kept her Twitter feed strictly professional until then, too. It was something they liked to laugh about in Kathy’s final weeks and months. They found even more humor in Kathy chowing down on a weed brownie on an airplane to Oklahoma to see Greyson win a film festival award or Kim learning to cook down marijuana to extract THC to bake those edibles. “It was like Breaking Bad in my house,” she says. (Kim’s two big future wishes for palliative care professionals: that they’re at the table when a patient with advanced cancer sets up an appointment with an oncologist and that they make more active efforts to legalize and decriminalize medical cannabis.) Those “funny weird challenges” are part of the reason why a terrible situation didn’t always feel terrible. When people ask Kim if it’s strange to sleep in the bed where her wife died, she tells them that it doesn’t feel weird or sad, “because nothing bad happened there.” Meanwhile, Greyson, who returned to college a few weeks after Kathy’s death, had his best semester last fall. “If you can find ways to laugh about things, it’s way better—and it certainly made life better for our son too,” Kim says. “It wasn’t that we were laughing and pretending like it wasn’t happening; we were laughing about the fact that it was happening. And that’s different than being in denial about it.”

Kathy, too, was cracking jokes until the end. She was still herself. “If we’d had six months or eight months when she’s coming home every day, and she’s throwing up from chemo, and she’s miserable—then I think the house would have sadder memories,” Kim says. “I mean, if I had to choose a way to die, I would choose how she went.”

There are some days that are hard, to be sure. New Year’s Eve was rough for Kim and Greyson. Kim melted into a puddle of tears taking down the Christmas decorations. She misses how Kathy would always encourage her to take naps on the weekends to help her spine condition, ankylosing spondylitis. But she’s found kindness from unexpected sources. After she broke down crying in a CarMax office because she saw a portrait of a kayak while selling Kathy’s car (“Kathy loved to kayak”), a CarMax employee surprised her by sending a watercolor of a kayak, along with a condolence note. Dyson shipped her a new vacuum when she broke the one Kathy had sworn by. And she likes to say the things that helped her the most while she cared for Kathy was not anything healthcare related but instead the dog kennel that kept their pups Dizzy and Mitzi (Rumi has since been added to the pack) free of charge for two months and discovering the Shipt grocery delivery service.

She’s kept busy too, throwing herself into her teaching at UVA and pushing other schools to weave LGBTQ inclusion into the curriculum. To that end, she’s getting set to deliver more presentations around the country, with upcoming stops in San Diego, Sacramento, and Philadelphia. At one of the first talks she gave after Kathy died, she recalls seeing people handing out Kleenex because they were crying—which was both a shock (“I’m used to no extremes of reactions in the audience”) and an eye opener.

“I’ve decided I think people change practice not based on facts. I’m starting to think people change practice based on stories,” she says. “Because I’ve been saying the same stuff. My whole career I’ve been trying to get people to make change. And no one really listened. Now they seem to listen because I’m talking about a person.”

Kim is thinking about that person near the end of my visit as we slush through the snow to get to The Lawn, a large grassy court designed by Thomas Jefferson more than 200 years ago. A few students are building a snowman while listening to Frozen music in the center of it, almost like they were pulled from a movie set themselves. That’s the way it always feels when she walks through the historic campus, Kim gushes, and Kathy would have loved their new life in Charlottesville just as much.

Not getting a chance to build those memories together will hurt forever, but Kathy still feels close. Always one to get in the last word, Kathy had scheduled emails to go out on certain dates in the future, after she had died. So when Kim checked her inbox on September 2, she blinked away tears as she stared at the subject line “Am I dead yet?” and the note that followed.

Hi honey,

I guess I can’t say “I’m not dead yet” anymore!

You are my one true love and I miss you already. I’m the luckiest woman who walked the planet because you were my wife. Cancer sucked, but it sucked less with you.

Your love, patience, hard work, humor are the only reasons I was

able to navigate this cancer and dying shit. Your love, tenderness, and

compassion made this bearable.

I love you forever and ever! k