A dispatch from the Zoom life.

By Amber Auslander

Once a week, a package arrives on my doorstep. Art prints fresh from friends’ Etsy pages. Holographic stickers to plaster on my laptop. Small gifts to myself, their presence announced by email notifications, or my roommate’s tiny Maltese mix, Dellie, frantically barking at the door.

In this new world of Zoom parties and endlessly updating group chats, many people are returning to hobbies of the heart and hand. My roommate, Dmitri, has started a small porch garden and is mending socks, occupying time previously spent in a vanished job. My other roommate, Taty, fills the kitchen with dishes and scents to rival the most extravagant of eateries, leaving brownies on the table with a handwritten note and a smiley face. My friend Ivy invites us to join him on video as he sews an endless array of colorful scarves.

“[These things] are almost like stimming,” my online friend Vin Tanner muses as we discuss this over Discord, referring to the grounding, repetitive physical behaviors most associated with autism. “Knowing you exist beyond typed words.”

It is the 42nd day of quarantine. I am sitting on my carpeted bedroom floor, which at this point hides too many memories of Pop-Tart crumbs past. I am imagining a time where the first thing that comes to mind is not this ever-looming pandemic. I am waiting for a day where the first and last things that occupy my hours do not involve sitting in front of my laptop or scrolling endlessly through my phone.

But this feeling is not new to me. I spent four years of high school sleep-deprived, mostly friendless, and perpetually online: nestled in my basement, sneaking blue-tinged Skype messages back and forth between e-friends and enemies. I became intimately aware of the ways in which technology can bring us together—teenagers baring their souls in text and digital drawings, pouring our hearts and traumas into one another like so many mother birds. I became just as familiar with the ways it can wedge us apart, spending enough hours burning my eyes against a bright white screen that I barely spoke with any of my real-life, fast-fading friends—an Ouroboros of isolation.

My mother used to question the presence of “the real” in my online friendships. “You don’t even know these people,” she’d scold, exasperation masking her lurking curiosity. “How do you know they’re not older men? How do you know they’re not trying to hurt you?”

What she was really wondering about was what any of our interactions truly meant—what does it mean to cry, to laugh, to be present in a space where hands or shoulders cannot touch?

This semester—my final semester at the University of Pennsylvania—I was given the opportunity to conduct research on Virginia Woolf, the letterpress, bookmaking, and paper under and for essayist and novelist Beth Kephart, whose class I had taken the year before.

One cold afternoon in late January, Beth and I explored the press firsthand through an introductory workshop at the University’s Common Press, crafting a collaborative broadside with the workshops’ other participants. Each of us was given an opportunity to craft a single sentence and place it upon the page, themed to the poetry of a season. Mary Tasillo, the studio manager, guided us patiently through the history of the letterpress, the supply and imperfections of the type available to us, how to place our text upside-down on a composing stick before finally inlaying the page with furniture.

For spending three hours in this underground room, our reward was two-fold: we were given the freedom to use the press however we would like (during open workshop hours, of course), and we left that day with a copy of our finished broadside. It sang verdant, inked in Kelly green, with all the petrichor of spring. My hands smelled of lead for hours afterwards, despite repeated washings. The press had embedded the smallest pieces of itself into me.

a ray of

HOPE

rare soft birdsong

I still miss

knowing you less

everything could

happen unless

nothing does

Cherry blossom,

I await your arrival

IMPATIENTLY

Daffodils pop up

to say HELLO!

The days march on. Barred from the letterpress by the pandemic and penned in my room, I find myself returning again and again to that three-hour eternity, to the scrape of the ink knife against the palette. To conversations I had with letterpress-owning women, who spoke with me about the tangible we now all so crave.

Lauren Faulkenberry, a North Carolina printer, told me, “I feel like the printer puts her mark on works that are made by hand, and when you hold a book that is letterpress printed, you get to experience some of what the printer experienced while making it. For me, there’s no substitute for feeling the various textures that you feel in a handmade, hand-printed object. It has a special kind of life in it that you feel when you hold it in your hands.”

Another printer, Joey Hannaford, contemplated the appeal of the press: “Setting type is physical, time consuming, and therefore a contemplative activity. For many people, the slow, deliberate process of setting type can increase one’s awareness of the deeper meanings of words and their relative range of interpretive possibilities.”

Holed up inside my bedroom, I am weightless in a way that leaves me prone to wonder, the curious counterpart to mind-wandering anxiety. Where I once blitzed through a book at breakneck speed, I take time to think about the other fingers that may have graced the page. I consider the placement of each word in poetry, the potent intricacies of white space.

Transient traces of human presence, a friendly bookshelf haunt. I think of the ladies of the letterpress sitting in front of their keyboards, the way I am sitting in front of mine, and I try to remember the scent of air when tinged with metal and ink.

Dellie’s anxious barking pierces through my fog, and a bolt of instinctual alarm drives me to my feet. Down the stairs, just past the door and the wide-eyed dog, kneeling to retrieve the package left by some quick-moving delivery driver.

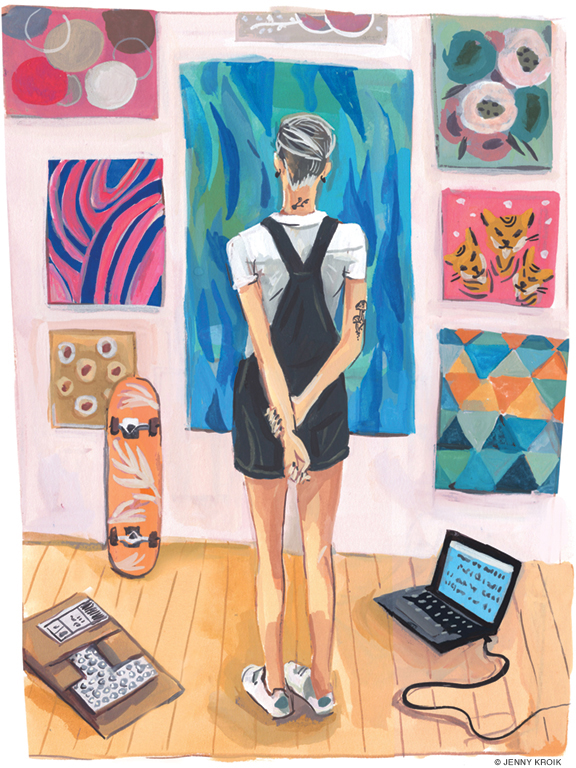

The most exciting part of any birthday party is fumbling through the wrapping paper to the prize beneath. Dashing back up to my reluctant refuge, I rip past the brown cardboard envelope flap and peel my gift from its container: a new print from Vin’s Gumroad store, a digital drawing of a woman disappearing into a virtual forest. I scan the edges of my room with a smile, wondering where its golden tint might best catch the sun.

Here is the present. Here are the flags and prints that line my walls, the overexposed Polaroids from long-ago sunlit days. Here is this new piece of art, in its vibrant yellows and greens and blues, a friendly name staring back at me. Here is a single tree outside of my bedroom window, in my backyard where the sun barely brushes.

Here are its blossoms, patiently blooming.

Amber Auslander C’20 lives in West Philadelphia.