After a century and a half, Penn’s oldest performing arts group is still going strong.

By Molly Petrilla

They’re calling this the “Year of Glee.”

The term has been used to end emails and to start conversations. It’s one of the first things their director will mention when you meet him, and there it is just above the official Penn Glee Club coat of arms and the words Celebrating 150 Years on their website page linking to a list of events marking that significant milestone. During 2011-2012 Penn’s all-male Glee Club has ambitious plans to celebrate its past successes, uncover more of its extensive history, and reconnect with long-lost alums.

But tonight, with the opening of their fall show fast approaching, they just want to practice their boy-band medley.

Scott Ventre EAS’13, a spirited high tenor, demonstrates the heads-down move that will end the number. They’ve re-appropriated the millennial classic “It’s Gonna Be Me” from ’N Sync, turning it into “It’s Gonna Be Glee,” and Ventre wants to see all heads snap down on the word glee. The 30 or so guys on stage practice the move with varying levels of ease, simultaneously hitting their harmonies.

As the head snapping continues, Glee Club Director C. Erik Nordgren Gr’01 steps in with a request of his own: “I’m still not hearing the gl- when you sing glee,” he says. “Explode the gl-.” Gl-s explode accordingly.

Clad in T-shirts, many of them advertising the show for which they’re rehearsing, the guys run the medley again. Voices high and low blend into a single, strong chorus, filling the empty theater that in two days will hold a sold-out crowd:

Don’t you know it’s true?

We sing and dance for you.

Not gonna lose pitch,

’Cause we’re not like that …

Baby, when you finally

Get to love somebody

Guess what?

It’s gonna be Glee.

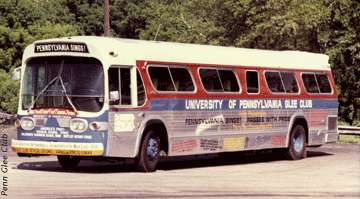

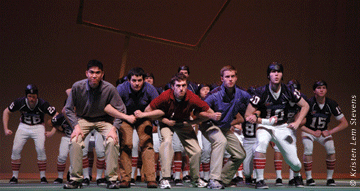

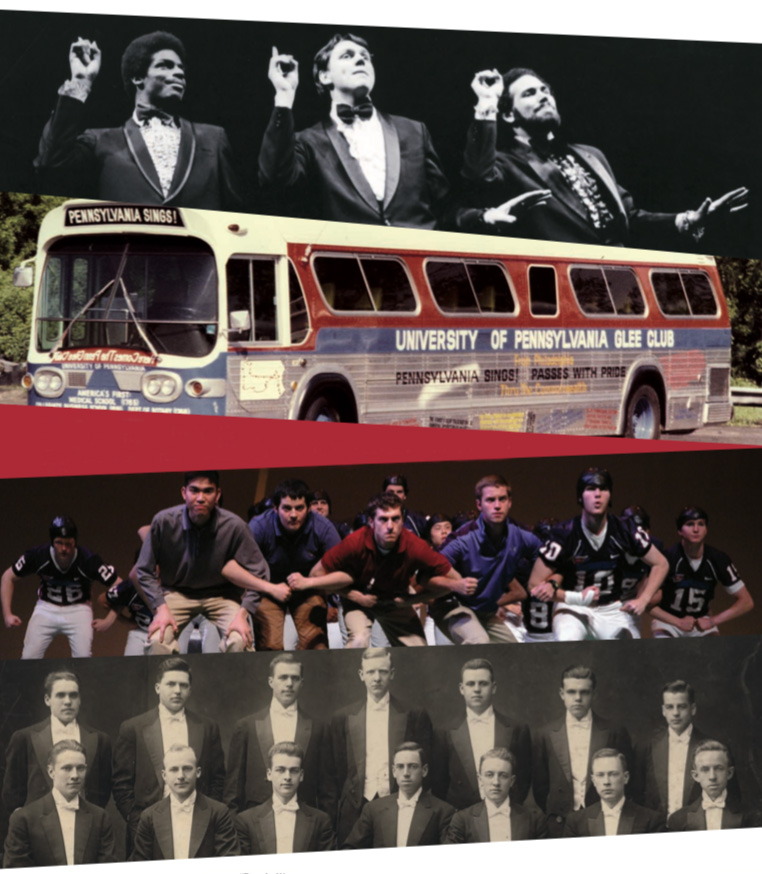

From left: Three Pennce—David Vaughn C’76, David Klipp, and Gene Schneyer C’75—perform “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy.” In 1976, the Glee Club toured Pennsylvania in the “graffiti bus,” a SEPTA loaner they had to repaint before returning. Guys & Balls: A Football Musical, Spring 2011.

But with all their trials, no men in College have a better time than

the members of the Glee Club, and as the tuneful ones of ’87 bid farewell

to these pleasant associations they cannot but sing to those left behind,

“On, gallant company !” and as the walls of “Old Penn” grow dim in

the distance, there will float back the answering refrain—

“Ben Franklin was his name,

And not unknown to fame;

The founder first was he

Of the U-ni-ver-si-tee.”

—1887 yearbook

It’s impossible to sum up the Penn Glee Club with a single adjective, or even several. But here, according to Nordgren, is what they’re not: They’re not stuffy or boring. They’re not a bunch of Ivy-League dweebs who turn up their noses at the thought of singing pop music. And, as much as it’s helped their image in the last few years, they’re not the toothpaste-commercial teens from the FOX TV show Glee, either. “I guess I’d say we’re a hybrid of the two stereotypes,” Nordgren adds. “We’re much more fun than the ‘boring’ stereotype, but not quite as Hollywood as the TV show.”

The Glee Club is the oldest performing-arts group at Penn and one of the oldest glee clubs in the country. While the emphasis clearly rests on vocals, they do other stuff, too: dancing, acting, writing skits. They sing songs from Broadway and Michael Jackson, along with serious classical pieces and spiritual works. They’re graduate students and engineers-in-training. Finance majors and budding biologists. Computer scientists and future lawyers. They grew up as far away as South Korea and Singapore and as close by as Philadelphia and New Jersey. They have girlfriends and they have boyfriends. Some listen to Bach, others to Lady Gaga.

“The diversity of the organization is what’s so lovely about it,” notes Eduardo Placer C’99, a Glee Club alumnus who now directs the group’s annual spring show. “What we share is a love of music and the ability to sing and harmonize with each other. It’s amazing how that just transcends anything else—academics, race, sexuality.”

Over the last 150 years, the club has performed with Frank Sinatra and Bill Cosby, appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show and Today, and sung and danced in multiple Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parades. They’ve given concerts alongside famous opera stars and in front of foreign dignitaries, and they’ve jetted off on performance tours around the United States and to more than 40 other countries.

The names and faces change from year to year, but even over so many decades, the group hasn’t strayed far from the combination of musicality and brotherhood that led eight undergraduates to found it in 1862. As the Civil War raged and a smallpox epidemic hit California, the Penn Glee Club prepared for its first performance. In a chapel at Ninth and Chestnut streets, the newly minted club sang in late 1862 for “an audience that was unusually select and large, the Hall filled to its utmost capacity.” Each singer wore red and blue ribbons in his buttonhole, making the group the first at Penn to wear those colors as part of its uniform.

By the end of 1865, the Glee Club had 20 members—more than any of the campus fraternities. (Remember that in those days, each class had only about 25 students.) It had also added a full board, including a business manager, and received top billing in the yearbook’s “University Record” of campus happenings. There, the group is described as having “already won for itself honourable laurels” and praised for earning more than $200 in a single concert.

Things hit a bit of a slump soon after that. In its yearbook, the class of 1872 credits itself with “reviving” the floundering Glee Club. That year, nearly every man in the senior class got together weekly to “pour forth the beautiful strains of Gaudeamus, Litoria, etc.” As a result, they write, “The Glee Club has brought us together, we have learned to know and love each other as we never could while merely meeting in the recitation room.”

The same 1872 yearbook lists separate Glee Clubs for the junior and sophomore classes, and the graduating seniors note that “we only hope that they will keep up the singing interest, (we are glad to know that their glee clubs are at least organized,) and if they arrive at a higher point of musical excellence than ourselves, we will not begrudge them the honor, since it will all redound to the glory of our well-beloved Alma Mater.”

By the turn of the century, a University-wide Glee Club had taken shape, replacing the class-specific ones. In those early days, the Glee Club offered one of the only outlets for musically inclined Penn students. A banjo group and mandolin club also existed, but the singers were consistently heaped with the greatest “honourable laurels,” as it were. They performed joint concerts with nearby colleges and traveled through the state on multi-city performance tours. They also sang at the Academy of Music and, by 1930, boasted a membership of more than 150 singers.

In the decade that followed, membership retreated to about 50 singers—much closer to the range it now hovers in; this year there are 41 singers—but the club’s performance schedule remained busy: local colleges, Philadelphia Orchestra collaborations, tours through the southern states.

“In the late 1940s, people didn’t travel as much as they do now,” says John Reardon W’51 WG’56. “When you grow up in a small rowhouse in Germantown, only going into Philadelphia a few times a year, Atlantic City seems like a pretty exotic place. The Glee Club took us out of our small bubbles and showed us the big world out there.”

During the academic year, Penn Glee Club members rehearse anywhere from six to 30 hours each week. That’s not including the time they spend performing—shows in the spring and fall; guest spots at University functions; singing tours around the world. As Glee Club alumnus Mark Glassman C’00 puts it: “We say that everyone who was in the Glee Club at least minored in it. Some people majored in it. And some of us are doing post-baccalaureates in it.”

Indeed, involvements with the club often last far longer than four years. Glassman has written the club’s spring show every year since he graduated, making this his 12th consecutive script. Robert Biron C’91 GGS’92 G’97 has choreographed the annual tap-dance finale since the late 1980s. Erik Nordgren joined the club as a singer in 1992 and has been its director for the last 12 years.

And then there’s the Granddaddy of Glee himself, the late Bruce Eglinton Montgomery. “Monty,” as he was re-christened at some point along the way, directed the Glee Club from 1956-2000 [“Monty in Full,” May|June 2000]—though, as several alumni say, “directed” seems like too narrow a description of his role.

“In many ways, Bruce taught us how to be men,” says Marc Platt C’79, now a prominent film and Broadway producer [“Passion Plays,” May|June 2006]. “We learned to walk tall and to be proud of who we were and what we were doing. Bruce also instilled a lot of creativity in me, and the notion of putting on a show. He cared about every performance as if it were opening night on Broadway—he was that professional and that focused. That had a tremendous impact on me.”

Most conversations with Glee Clubbers present and past invariably drift to Montgomery, who quite literally wrote the book on the Penn Glee Club. (It’s called Brothers, Sing On! and was released in 2005, three years before his death.) Even those who didn’t sing under his baton are fascinated with him—and yes, several admit, jealous that they didn’t get to know him personally.

Though there had been one foray into a staged production—1928’s Hades, Inc.—when Montgomery took over the club in 1956, they still gave traditional, stand-on-risers-in-a-blazer concerts. Not a single choreographed boy-band medley in sight. He quickly beefed up their concert schedule—by 1960, they were performing more than 50 times a year—but interest in old-school glee clubs like Penn’s had plummeted by the end of the decade.

“It was the height of the Vietnam War, and the concept of an all-male glee club was becoming an anachronism,” explains Robert Hallock W’71. “There was much less interest in choral singing or in any traditional organized activities on campus, so there was a lot of apathy—and at times antagonism—toward what were considered establishment-type activities. Bruce Montgomery was very savvy with regard to creating excitement around concerts, and he knew that we had to do something to increase interest.”

They decided to create a themed show that would be more like a night out on Broadway than an all-male choir concert. Calling it Handel with Hair, they cast aside the choral risers and built colorful wooden cubes and ladders. They swapped their dressy clothes for more modern ones: vests, shorts, bellbottom jeans. And perhaps most significantly, they closed the show with a medley (and corresponding moment of nudity) from the year’s edgiest Broadway musical, Hair.

“All over the country, glee clubs were rolling over and dying like mastodons,” Montgomery writes in Brothers, Sing On! “With Handel with Hair, we proved that we were a valid voice for more than just singing.”

Many alumni say that the transition from concerts to shows was one of Montgomery’s greatest legacies, rivaled only by the hundreds of songs he arranged for all-male voices. “Before Monty,” adds Robert Biron, “the Glee Club was a stand-up singing group. He re-energized it with a sense of theater and a larger mission of bringing music to the world through song and dance.”

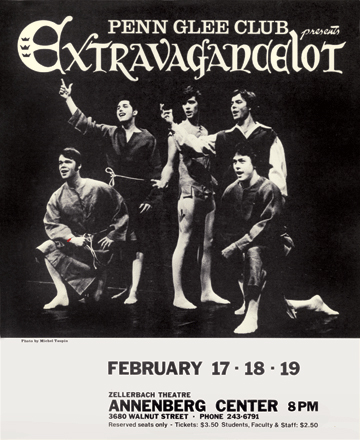

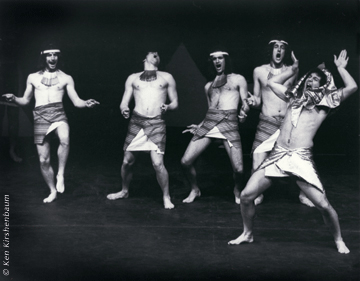

Starting with 1969’s Handel with Hair, the Glee Club updated its image with themed shows. Later shows continued the word play—like Extravagancelot in 1977, 1979’s Sing Tut (below), and the Fall 2010 show, Rock Hard Cafe (above right)—but dropped the nudity.

After Handel with Hair, the new show format continued. Yet even as more modern music joined the club’s repertoire, Montgomery refused to oust the older, more traditional songs that he loved. “The shows became more relaxed and entertaining, but we still kept the elements of classical choral singing as at least part of what we did,” Hallock notes.

In 2000, exactly 50 years after he came to Penn, Montgomery retired. Members from that time remember it as tumultuous and sad. They worried about what would happen to their club—Monty’s club. Monty worried, too.

He decided to turn things over to his student director, a talented and devoted graduate student named Erik Nordgren. Always one to embrace his own flair for the dramatic, Montgomery wanted a Big Reveal moment to announce his successor and chose his final show with the club to do it. He writes:

“At one spot in the program—not even announced to the singers ahead of time—I mentioned to everyone that I had been blessed for some years with a truly outstanding student conductor, and I called on Erik Nordgren to conduct ‘Ride the Chariot’ while I stood in the chorus and sang. He did his customary fine job and bowed appreciatively to the enthusiastic applause. Then I put my arm around his shoulders, walked him down to the front of the stage, and said, ‘And ladies and gentlemen, now that you’ve seen Erik do what he does so well, let me re-introduce him as my successor: the next director of the University of Pennsylvania Glee Club.’ The place went wild!”

Nordgren has led the club ever since, maintaining the blend of Broadway showmanship and challenging classical music that Montgomery instituted. “He always had a knack for stagecraft and making a presentation very appealing,” Nordgren says of his predecessor. “I like to think that I’ve continued to build on the transformation that Monty began.”

The girls in the audience scream or cry or, in more than a few instances, both. It’s the late 1960s, and a group of young men, singers, have traveled abroad to perform in Lima, Peru. The audience is too large for the city’s downtown theater, so an outdoor stage has been erected instead. After the show, screaming fans race up to the young men, clawing at their clothes and begging them for autographs.

Who are the young men inducing this fervor? The Penn Glee Club, of course.

As a club member recalled in the 1970 Penn yearbook: “We were really, truly, like celebrities. The girls swooned over us wherever we went. As we walked off from our last concert … the girls grabbed our clothing and our matriculation cards. They wanted everything we had. One girl ripped off Mr. Montgomery’s shirt front and asked him to autograph it. This attention we’ll never get at Penn.”

Maybe not, but a similar scene erupted exactly three decades later when the club traveled to Japan in 1999. “For reasons that I still do not understand, we were extraordinarily popular and extraordinarily well-received there,” Mark Glassman recalls. “Girls were screaming and crying. We would look at each other and be like, ‘Why are we the Beatles right now?’ It was a very odd phenomenon that had many of us contemplating canceling our flights home. You’re probably hard-pressed to find a group that loves itself more than the Glee Club, so it was really nice to have other people shower us with the praise that we always knew we deserved, particularly when those people were members of the opposite sex.”

Aside from introducing scripted shows, Montgomery also brought the club on its first international tour—a tradition that endures to this day. The emphasis on travel was, and still is, a big draw for new members. Biron, now the president of the Glee Club Graduate Club, still remembers the marketing flyer he received just before heading off to Penn in the late 1980s: Join the Glee Club and Sing the World … Is More Than Just a Slogan. (Monty, a one-time PR staffer at Penn, was never at a loss for a stirring call to action.)

In Brothers, Sing On!, Montgomery makes frequent reference to the club’s role as unofficial diplomats on these trips. Along with the rock-star moments, he also notes that the club’s journey to Latin America in 1969 coincided with a period of strained relations between the US and Peru. The US ambassador to Peru had warned Montgomery that traveling there could be dangerous, but the Glee Club made the trip anyway and swiftly won new admirers. In fact, a Peruvian college student approached them after a performance and said, in English: “If President Nixon had sent you before tonight, we would not know hate in governments—we would know the love of people.” And following that now-legendary trip, TheNew York Times wrote that the Penn Glee Club “has created greater understanding between the United States and the people of South America than would be possible at this time on higher diplomatic planes.”

Two years later, the Glee Club headed off on a 1971 European tour and captivated another continent. According to Montgomery, a Finnish singer even remarked: “You must enjoy a happy place at your university for it to send you on such a wonderful tour. But I wonder if they know how much better we understand Americans now because you have been here? We will talk about this for a long, long time.”

“We sort of refer to ourselves as being the ‘musical ambassadors’ of Penn,” Nordgren explains. “I don’t think any administrator at Penn has ever used that term, but we certainly say that about ourselves, and I think we can legitimately claim that there’s a lot of truth to that.

“There’s a cliché about music being the universal language,” he continues, “but we really see where that comes from when we travel. We perform in places where the audience clearly didn’t understand the [English] lyrics we were singing, yet they appreciate so much what we’re doing. They get it. Our performances cross the boundaries of language quite easily.”

Biron recalls one such moment from a trip to Hungary in 1990. The club stayed at a campground during summer-camp season and put together a huge campfire at sundown. “The whole Glee Club was there with dozens of these camp kids, and we wound up exchanging music with each other,” he says. “We would sing a song to them, then they would sing a song to us. That went on well into the night. At one point, this one little boy was shyly singing some song and then a little girl joined him and then a few others and a few others. We got wind that it was the Transylvanian Anthem, which had been banned for half a century. It was incredible. That’s exactly what music can do—it can break down barriers and bring everyone closer together.”

And there was the occasional non-musical crosscultural experience, too. On the same 1971 tour that earned them their Finnish fan, a Yugoslavian college student approached the guys and asked whether they were in town for an international basketball tournament. “We learned that it was an open tournament and, with a borrowed ball, we put together a team on the spot,” Montgomery writes of the incident. The impromptu Glee team came in third place.

But really, whether they’re headed overseas or just up the New Jersey Turnpike, “the locations are never that important,” Greg Suss C’75 admits. “It’s more about the experience of getting on a bus, getting on a stage, staying in a hotel. You learn a lot about each other on those trips. You see each other at best and at worst, and that promotes these deep relationships.”

The glee in Glee Club actually has nothing to do with its members’ exuberance. In the case of a singing group, glee goes by another definition: a song scored for three or more voices, spanning any number of genres and typically sung without accompaniment.

“I was always drawn to the all-male choral sound,” notes Scott Ventre, the junior who currently serves as the club historian. “Men can sing very high, men can sing very low, and men can blend, too. When you listen to an all-male group like ours, you really get the full range of what a chord can sound like.”

“I wasn’t looking for the all-male sound,” Biron says. “I think the all-male sound found me. The [tenor 1, tenor 2, baritone, bass] arrangement is a wonderful part of the musical lexicon, and it’s a great sound. There are so many wonderful arrangements for T-T-B-B that it’s great to keep that strong. Having a group that can produce that sound is not as common now, but it should still be available and enjoyed.”

“There is something about the anonymity in the group—the way your voice is masked by the voice of 40 other people—that’s really magical,” adds Placer. “You produce your own individual sound, but it becomes part of something bigger. It’s humbling, and it’s really magical to give over to something like that.”

In addition to its unique all-male sound, the club is known for its enormous repertoire. By the time a Glee Clubber graduates, he’ll have learned about 100 songs, according to Nordgren. About 20 of those songs have been taught to all members since the 1950s, including the Afterglow, Grace, and Toast that Montgomery wrote and the centuries-old University spirit numbers.

“We truly have a song for every occasion,” Biron says. “When we traveled to Austria and Hungary my junior year, we would find ourselves just walking around Budapest, and we could park ourselves at a square and just start singing. We could sing for an hour straight, easy, and we did.”

That same shared musical lexicon often leads to spontaneous outbursts of song, prompted by one guy shouting out a cue line from the club’s latest show or simply holding out a first note. “Singing is what we do, and whenever we’re together, that’s what happens,” says Michael Keutmann C’05 GEd’09. “Whether it be in a car or on a bus or up on a stage, we’re singing.”

It’s not unusual to spot Glee Clubbers hanging out in small groups around Penn, even when they aren’t performing or rehearsing. Stroll around campus for a few hours, and you’ll probably see two of the guys grabbing lunch together in Così or maybe a trio waiting for crepes in Houston Hall.

“I think the Glee Club has a really special way of combining the music aspect and the social aspect,” Nordgren says. So it’s sort of like a fraternity, but with show tunes? “We do have some fraternal aspects in place for the sake of fostering brotherhood,” he responds, “which in turns improves the quality of our performances.”

As Keutmann notes, “It’s hard for me to distinguish Glee Club from college because my Glee Club friends were also my best friends, and whenever I went anywhere I was hanging out with Glee Club people.”

And because of the music that binds them, the feeling of Glee-based brotherhood transcends individual graduation years, Biron says: “When we have alumni events, alumni come from across decades—many of whom have never met before—but they can all come together and sing the same songs.”

In February, the Glee Club will celebrate its big anniversary with a gala in the Zellerbach Theater and a new show focused on its storied history. Then in May, alumni and current members will head off on a cruise—destination not yet finalized—to perform both officially and casually.

And beyond that? “Much like with Darwinism, if you can’t adapt to changing conditions, then you’ll go extinct,” Nordgren says. “One concept I can’t take credit for—Monty relayed it to me—is that the Glee Club needs to be adaptable and flexible to remain relevant. It couldn’t be the Glee Club of 1900 in 1950, and it can’t be the Glee Club of 1950 in 2000. Pop culture shifts. People’s attitudes shift. Musical tastes and cultural influences are constantly shifting, too.”

Still, even as it evolves, the club in many ways remains the same. “The thing that I think is so amazing about an institution like the Glee Club is that the sound of the group hasn’t really changed,” Placer says. “For 150 years, men ages 18-22 have come together in song. We as individuals graduate and move on, but the core sound stays the same.”

“One of the things the club likes to do a lot is talk about how old it is, especially compared to other groups at Penn or other glee clubs,” Mark Glassman adds. “It is in fact very old. But it’s not a surprise to me that it’s 150 years old, and I wouldn’t be surprised if it continues in very good health for the next 150 years, if not more. There really is something to be said for singing in harmony with your friends.”

Molly Petrilla C’06 writes frequently for the Gazette and oversees the magazine’s arts & culture blog.