Penn alumni are at the forefront of a growing movement to make socializing safe for the world’s nerds.

By Caren Lissner Matzner | Illustration by Graham Roumieu

Inside a dimly lit bar near the Brooklyn waterfront on a blustery October night, young professionals are sitting at small tables, drinking and checking each other out in two reflecting pools near the front of the room. A young man with a master’s degree in digital media walks onto a stage to give a slide presentation on the history and utility of infographics—and the crowd goes silent.

For 20 minutes, the man presents charts covering everything from worldwide farm production of soybeans to why there aren’t enough single datable black men (just to mix things up a little).

When he finishes presenting and departs the stage, Matt Wasowski C’96 walks on. Tall and blond, he is lit by the stage lights and appears again in the reflecting pools.

“Before the presentation, I asked how many of you knew what an infographic was, and six people raised their hands,” he says. “How many of you feel like you know what infographics are now?” He pauses to survey the raised hands. “That’s way more than seven people!”

Wearing a button-down shirt, his hair cut boyishly short, Wasowski looks professional and eager, but he’s not what one would think of as a nerd. Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary defines a nerd as “an unstylish, unattractive, or socially inept person, especially one slavishly devoted to intellectual or academic pursuits.” Wasowski not only follows sports, he’s written a book on the subject. (True, the title is It’s Okay to Like Sports: How Women, Intellectuals, and Artists Can Find Cultural Value in Athletics, but still.) And he’s presumably even kissed his live-in girlfriend (Sarah Brockett C’99), who plays bass guitar in an indie band.

But Wasowski is a nerd. More than that, he is officially the “nerd boss” of New York.

Over the last decade, Wasowski has been part of a group of Penn acquaintances who helped pollinate America and then the world with a series of events called Nerd Nite (nerdnite.com) that urge participants to “be there and be square.” The monthly nights of learning (and drinking) have launched in nearly 30 cities around the world, from Amsterdam to Wellington, New Zealand (though most venues are still in the US).

Nerd Nites in New York and San Francisco have routinely lured as many as 300 attendees, leading many to ask why people are willing to pack rooms on weekend nights in order to learn from scholarly presentations. Some credit the Internet with making it easier for formerly isolated brainiacs to find each other. Others point to computers, but in a different way—they note that yesterday’s tech-nerds have become today’s Fortune 500 billionaires, so it’s become more acceptable to be smart and weird. Still others find it enthralling to simply consider the evolution of once pejorative terms like nerd, and to wonder what it says about the direction of society.

So how did an insult that once typically accompanied being shoved into a school locker become a term with which people proudly self-identify, and what does it mean for the future of community and communications? And, well, is it still an insult?

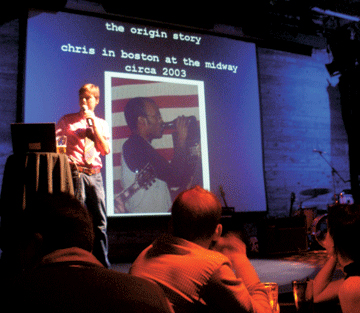

The first Nerd Nite was held in Boston in 2003. Chris Balakrishnan C’97 used to hang out at a bar, the Midway Café in the Jamaica Plains section. He was earning his PhD in biology at Boston University and often took trips to Cameroon to study the evolution of birds.

“I’d disappear from the scene for three months at a time every year,” explains Balakrishnan from his current home base in Illinois, where he is doing post-doctoral work. “They’d be curious about what I did, the owners and the bartender. One owner said I should give a slide show at the bar. So you can imagine, it’s kind of a dive bar, and they have a stage, so usually there are kind of terrible bands, noisy rock and roll. I went home and I thought, ‘I could get people to tell about the weird things they do with [their] lives.’”

Balakrishnan—who is listed on the group’s website as “Nerd Nite guru”— set up the first Nerd Nite. He expected only a few of his graduate school friends to come out.

“I was like a nervous teenager who tried to have a party,” he says. “I wasn’t sure anyone would show up. We got a good crowd. Probably around 30 people showed up the first night. The bartenders and audience members felt comfortable asking questions, cracking jokes, heckling. We try to keep that going at all the Nerd Nites now, really casual and light-hearted and funny.”

In fact, there is an element of low culture in the Nerd Nites, with the presenters and audience members often invoking either excrement or sex in otherwise scholarly presentations. The most popular subjects have mixed high and low culture, like the history of the world as seen through barbecuing, or the sociology of sex robots. Animal sex is a frequent theme.

“My presentation was on indigobirds, which is one word, and they’re an unusual kind of bird,” says Balakrishnan. “They’re known as brood parasites, so instead of raising their own, birds lay eggs in the nest of another bird and the other bird raises them.”

Nerd Nites began running monthly in Boston. Balakrishnan knew Wasowski from Penn and encouraged him to bring Nerd Nite to New York, where Wasowski had been running team trivia nights since 2001.

Bar trivia, in fact, is the likely father of Nerd Nite—perhaps the first hint that young professionals wanted to do something in a social setting besides drink and strike out with the opposite sex. “Quiz nights” began at pubs in the United Kingdom and exploded in bars in Philly in the late 1990s, drawing players from the colleges nearby. Penn students could play in a different bar almost every night.

The practice was a bit slow to catch on in New York; there were only a few such nights when The New York Times wrote about the trend in 2001. In 2000, Wasowski, who had come to New York from Philly a year earlier to work for an educational software company, brought trivia to a bar on the Upper West Side.

Over the next few years, he also visited Balakrishnan and attended the Boston Nerd Nite, but thought, “No one in New York would ever go to this.” The nights in Boston were scientific, fueled largely by graduate students. But Balakrishnan kept trying to convince Wasowski. So Wasowski debuted the New York version in 2006, and added side attractions like speed dating and jugglers.

Since then, Wasowski—who also holds the title “big boss”—has trained a cadre of fellow “nerd bosses” who have taken the event to cities around the globe, using an “official Nerd Nite starter kit.”

Though he ranked seventh in his class of more than 700 at Lakewood High School near Cleveland and was president of the National Honor Society, Wasowski didn’t get bullied in school due to his smarts—unlike some of the other Nerd Nite fans.

“I always thought Matt was cool,” says George Pasles C’97, who reveals that he was beaten up on the bus as a kid because he spent his quality time with computers, and who has frequently attended the New York Nerd Nites since the premiere in March 2006.

The idea quickly got noticed by local publications and gained a big enough following to outgrow its first home in the East Village. Wasowski moved it to Galapagos, a large art space among the brick-lined waterfront streets of the artsy Brooklyn neighborhood known as DUMBO, short for Down Under the Manhattan Bridge Overpass. The monthly event began selling out, with 300 people buying $10 tickets to see three slide shows and socialize.

Besides infographics, presentations have focused on the iconography in Michael Jackson videos, hunger and obesity in Harlem (that one by JC Dwyer C’00, who works in policy for the Texas Food Bank Network and also runs Nerd Nite Austin), and something called “sexual robotics” that became an instant classic—at least as far as Pasles was concerned.

After this presentation, in which NYU medical anthropology scholar Laura Duncan touched on items such as “drilldos” and women’s health, Pasles was intrigued. In true nerd fashion, he emailed her in the middle of the night and expected not to hear back. Two years later, they live together.

“She asked me out,” Pasles maintains.

Of the propensity for sex and scatology in otherwise intellectual presentations, Wasowski says, “Sex is popular with everyone. In scientific terms, you can say ‘procreate’ and ‘masturbate’ with more of a straight face. We’ve had cephalopod sex presentations. Fish and birds. Insects. Name the species and there has probably been a presentation about it having sex.”

He also noted that in New York, people are “notorious for having four-second attention spans,” so a base topic certainly piques one’s interest.

But perhaps there’s something more at work. Joking about sex or toilet habits is a way to show that you’ve grown out of your awkward adolescent shell.

Lucy Laird C’96 runs the nights in San Francisco, where they debuted in 2009. Attendees pay an $8 cover charge. They have lured 150 to 350 people per night.

“It was just really awesome and it had a great vibe and so many people showed up,” Laird says of her first Nerd Nite. “We’ve had so many good presenters. A guy last year was a specialist on the atmosphere of Mars. He was very nerdy and sits in an office all day, looking at numbers. But he was just hilarious on stage. He had a great sense of humor but deep, deep nerdiness, and he was able to draw the crowd into that.”

Michael Nierenberg C’05 actually had no idea that the Nerd Nite concept came from Penn grads when he gave a presentation on predicting mortgage performance last February (he learned about the event from a non-Penn alum co-worker at his financial firm). He says that San Francisco is the perfect place for Nerd Nite because so many people are in technology and academic fields.

“Even if they’re not a nerd, they’re nerd-curious,” he says, without a hint of irony.

Author and commentator Stefan Fatsis C’85 says the popularity of Nerd Nite is a sign of changing times and changing technology.

He gave a presentation at Nerd Nite DC in 2010 about the history and culture of Scrabble, which was also the topic of his best-selling nonfiction book about competitive Scrabble, Word Freak, which came out in 2001 and was republished in its 10th edition this year [“Man of Letters,” Sept|Oct 2001].

“It seems to me there is a natural curiosity that a lot of media don’t satisfy, to be able to listen to interesting people who have eclectic passions talk intelligently with a sense of humor in a collectivist setting,” Fatsis says. “I think that’s incredibly appealing to a culture that can marginalize and discount and make fun of unusual interests. And it’s fun to get together in a cool environment and have a beer and just learn about something you didn’t know about.

“It’s not just journalists. It’s actually people who are in these worlds. It’s a wonderful reminder of how diverse and colorful life is outside of our own little bubbles,” he adds. “We are more willing to learn about something we wouldn’t have considered in the pre-digital age. We’re more open to this vast trough of ideas and information we can access instantly now. Maybe what Nerd Nite does is take people who have become accustomed to seeing and reading and learning about disparate subjects and bring them together in a physical place.”

Jane Willenbring, an assistant professor of earth and environmental science at Penn—who says she was picked on in school in North Dakota because “I was a good student … and I also had odd teeth.”—presented at Philadelphia Nerd Nite in October. “What I did definitely notice was it was a packed house. I couldn’t believe there were so many kindred spirits out there,” she recalls. “I was talking about how we can use the past, like the geologic record, to figure out future warming scenarios that would affect the East Antarctic ice sheet.”

Willenbring says the meaning of nerd has definitely shifted. “I think that it refers to people who really get into one specific topic quite a bit, and other things take a back seat. Steve Jobs could be considered a nerd, but in the last 10 years or something like that, people have just started to value getting into one specific line of work,” she says. “I don’t really know what constitutes a nerd, but it seems like you get so into something that you let other parts of your life sort of flounder. People don’t dress very well or they have odd [habits] because they don’t care about certain parts of their life. But that’s more acceptable nowadays, that you don’t have to have everything together if you are attached or motivated to work on one specific thing.”

There are various theories about where the term nerd came from. Dr. Seuss mentioned a character called a “nerd” in his 1950 children’s book If I Ran the Zoo, although there was nothing special about the nerd (it was just part of a rhyming sentence). A year later, Newsweek said that among teenagers in Detroit, “Someone who once would be called a drip or a square is now, regrettably, a nerd.” The slang got reprinted elsewhere, including in an Associated Press story three years later.

Some believe it’s not possible for the Seuss character and the Detroit term to be linked because the terms were too close in succession. Ben Zimmer, the former New York Times “On Language” columnist, wrote in August in an essay in The Boston Globe, “Speculation about the word’s origin began brewing in the 1980s. [Some believe] nerd had something to do with Mortimer Snerd, the dummy used by ventriloquist Edgar Bergen beginning in the late 1930s … Nerd has also been explained as a variation on nert, surfer slang for a nut … And then there are the acronyms, always a popular source of faux etymology—for example, ‘Neurotic Engineers in R&D.’”

While the term’s origin may be disputed, most agree that it caught fire in the 1980s, an era in which pop culture exploded. Cable television expanded, computers became accessible to the average youth, and suddenly, there were shows and movies focusing on those teenage computer users. TV programs like Whiz Kids and Square Pegs and teen films like Sixteen Candles and The Breakfast Club highlighted different social groups in schools, including jocks, cheerleaders, and nerds. And of course the Revenge of the Nerds film franchise—the original appeared in 1984, followed by sequels in 1987, 1992, and 1994—put nerds front and center.

By the time the generation of 1980s nerds grew up, they began having a sense of humor about their youthful struggles to fit in, and perhaps a sense of pride of having overcome the taunting. Even Hollywood icons like Nicole Kidman and Sharon Stone started claiming they had been outcasts in school, while it was the rare starlet who would admit to having been Homecoming Queen.

Brainy outcasts had been around for decades, including Dalton Doiley in the Archie comics (who was an inventor), but nerds represent something new in the culture. “I don’t think [the word nerd] was around even when I was a grad student,” says Mitchell P. Marcus, the RCA Professor of Artificial Intelligence in Penn’s Department of Computer and Information Science (and an A-list nerd based on that title alone), who has been teaching linguistics and computers here since 1987. “It really has changed. It’s one of those situations where people have taken a word applied to them that’s negative and turned it into a positive by kind of taking it over. I was at the [MIT] Artificial Intelligence Lab in the early ’70s and the word people used to refer to themselves in the same positive way was ‘hacker,’ which originally meant something quite positive. Then it became a quite negative word.”

These days nerd is mostly used “with a heavy dose of irony,” Fatsis says. “My nerd passion, Scrabble, is something easily mocked. If you mention that you memorize tens of thousands of words to play a game, you get lots of looks. Or, you used to get looks. But I wrote a book about that. It made people appreciate a world they didn’t know about. Hundreds of thousands of people now play Scrabble because it’s easy to do it digitally. Nobody sort of laughs about this game anymore, except the recent news about some guy who asked [officials] to strip search his opponent because he was accused of hiding a tile.”

Most of those interviewed agree that Nerd Nite is a sign of the Internet making it acceptable to love one unique thing. But Pasles says he was still taken aback by hearing the term used in a positive way.

“That’s one of the things that’s hard to get over,” he says. “As someone who had a Commodore 64, I was brutalized for being a nerd. A few years ago, Time Out New York or New York Magazine had a picture of a hipster with the words, ‘Nerd is Cool.’ It was hard for me to take. Now, everyone is using a computer; all movies are based on comic books. Nerd is not a putdown anymore. It’s a word that has no meaning beyond describing someone who is interested in something.”

The ease of communications, and the accessibility of technology, has changed worlds in more than one way. Pasles might not have had the courage to go right up to the dark-haired girl who presented a slide show on sex and technology, but e-mail was the great equalizer. (For those wondering, his missive said something like, “Your presentation was shocking to most of the people there but I wasn’t shocked.”)

Future generations of Penn students will likely be filled with many whose parents met, in some form, because of the Internet—not just from computer dating, but because of activities that were publicized or popularized over newsgroups, Facebook, and social networks yet to come that allow people with unique interests to find each other.

“You hate when something obscure and cool like a band no one’s ever heard of becomes a catch phrase,” says Lucy Laird. “I hope kids these days understand what being a nerd is about, rather than thinking it [only] means being really smart and making a lot of money in technology. It means being very passionate and consumed by knowledge, and taking everything to the next level.”

At October’s New York Nerd Nite, Wasowski announced that a small publishing company had made a deal to start a bimonthly Nerd Nite magazine—the old-fashioned, printed kind—so that people in one part of the world can learn the same things as those in another. Subscription cost is $40 annually, according to the Nerd Nite website. Promised for the first issue, scheduled to appear in January, are articles on Stomatopods (aka “mantis shrimp”)—“thumbsplitters of the briny deep”—and “Jumpsuits! The garment of tomorrow, today.”

“We think every single person on Earth, in some form, is a nerd,” Wasowski says. “Every single person knows one thing at least more than anyone else does. Probably someone like [New England Patriots quarterback] Tom Brady, the typical definition of an anti-nerd or jock, could tell you how to run the exact pass route to avoid a safety 12 yards from the line of scrimmage. No Trekkie or scientist can tell you that.

“The big point the publishing company made is, most things now really do tend to skew and cater toward the lowest common denominator,” Wasowski adds. “This shows people want to be challenged.”

Fatsis sees a bigger picture, that the evolution of the word nerdreflects shifts in the way people communicate, learn, and meet. Future generations will look at knowledge differently. “It’s exposure,” he says. “Everything has an opportunity now to find a community. The Internet serves that very democratizing effect.”

Caren Lissner Matzner C’93 lives in Hoboken with her family and writes novels. See carenlissner.com for more nerdery.