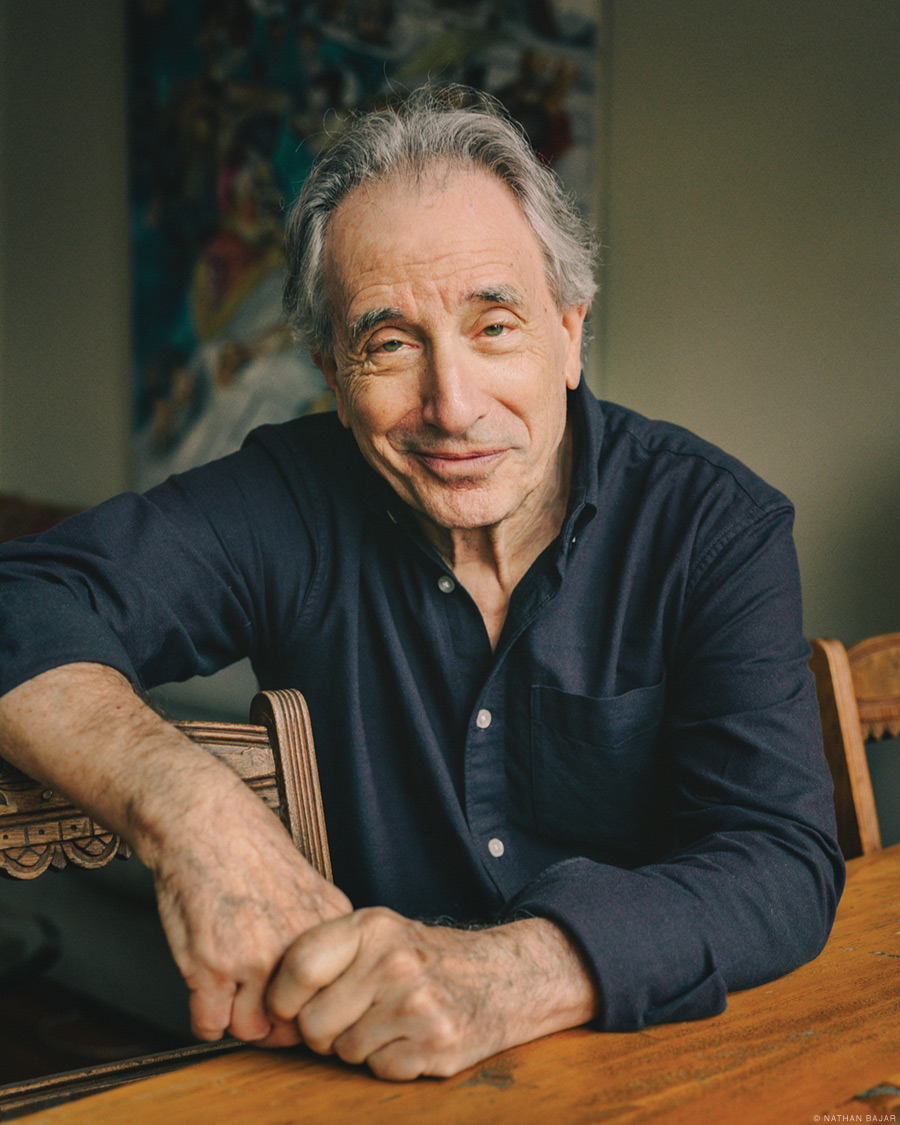

His acclaimed starring turn in Harmony was cut short by the harsh economics of Broadway musicals, but the theater, film, and TV stalwart is still looking ahead after seven decades in the spotlight.

By Jonathan Takiff | Photography by Nathan Bajar

Chip Zien C’69 has been having senior moments. The very best kind. Repeatedly.

At the tender age of 76, he’s gotten to bask in the biggest, juiciest role in his near-lifelong career as a theater, film, and television actor and singer, top-billed in Barry Manilow and Bruce Sussman’s ultra-tuneful Broadway musical Harmony.

Painfully, the show’s run abruptly ended in February—a victim of the post-holidays Broadway sales doldrums. But Zien’s tour-de-force performance is still resonating in the minds and hearts of those lucky enough to have witnessed it live or relish it via the original cast album—available on streaming music services and CD. And the stage turn still seems likely to earn him a Tony nomination for “Best Lead Actor in a Musical” when announcements come on April 30, if not the whole megillah when the awards are presented in June.

“This may be the best part I’ve ever been given,” Zien mused after an early December Sunday matinee at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre. “It’s a big story with a vital message. And to get this opportunity and responsibility at this stage in my life … well, it’s really been kind of overwhelming.”

First downtown and then on Broadway for a collective 170 performances, Chip Zien both stopped the show and stitched it together—singing and dancing, jesting and lamenting as the lead character, nicknamed Rabbi and officially Josef Roman Cycowski, a Polish cantor who’d rather sing secular. Harmony relates the true saga of the Comedian Harmonists, a globally acclaimed six-man singing and clowning ensemble spawned in Weimar Germany. Zien was on stage throughout, both narrating this memory piece (as its 87-year-old, sole surviving group member) and shadowing his young adult self. And to make sure he never caught his breath, Zien also popped up—surprise!—in a variety of cameo roles portraying famous figures of the period for extra comic and dramatic effect. (As many as five “carefully choreographed” hair and costume people swarmed around him backstage to make the transitions possible, he revealed.)

Half-Jewish, half-gentile, the Comedian Harmonists were a world-class study in cultural assimilation, brotherhood, and sweet, sweet vocal harmony. The “Boy Band of their day” (as Harmony show marketers liked to say), they traveled well, headlining at Carnegie Hall in 1933 and co-billed and performing with Josephine Baker in the Ziegfeld Follies of 1934. As their tributetells it, the group could have carved out a permanent career in the US, but foolishly went back to Germany just as the Nazis were tightening their totalitarian grip and ramping up their Aryan purity campaign. The Harmonists were initially granted a propagandistic “pass” as cultural ambassadors and naively hoped the hatred would pass. But when they dared to mock the repressive regime in song and dance routines, their numerous recordings and films were confiscated and burned, the group forced to disband, flee into exile, or (in some family members’ cases) suffer extermination. Today, for 99.9 percent of the world’s population it’s as if this popular entertainment phenomenon never existed.

“So this is more than just the Harmonists’ story,” Zien reflected. “It’s also about a moment in history when democracy slid into a fascist dictatorship and did some of the worst things imaginable, and the Harmonists were witnesses to it. And with antisemitism rearing its ugly head again, the timing of the production seemed prescient.”

Long a beloved figure in the New York stage community, with more than 15 Broadway productions under his belt, Zien has enjoyed originating major roles in significant stage shows before. Most notably he played the neurotic psychiatrist Mendel in William Finn and James Lapine’s Falsettos (1992–93) and the story-catalyzing Baker in Stephen Sondheim and Lapine’s fairytale mashup Into the Woods (1987–89).

In both outings, Zien experienced the thrill of having material tooled specially to suit his talents.

“When Steve [Sondheim] came to an Into the Woods rehearsal to first play us ‘No More’”—the show’s deepest diving, second act ballad—“my heart almost stopped,” Zien recalled. “He’d set it in my optimum singing key—D-flat.”

Zien was likewise a key figure in the 10-years-plus shaping of Falsettos, having played principal roles in the three prior one-acts (collectively referred to as The Marvin Trilogy) that then coalesced into a Broadway triumph.

At nearly three decades, Harmony’s development saga stretched even longer, and the latest version seemed to have been reworked specifically to exploit Zien’s versatility as a brash comedian; dramatic actor; big, belting singer; and decent hoofer. His plot-stitching role as the elder Rabbi (he prefers “Rabbi Emeritus”) didn’t even exist in earlier renderings of the show—not the regional productions in San Diego (1997), Atlanta (2013), and Los Angeles (2014), nor in celebrations of the material by popmeister Manilow on his 2004 Scores album and tour.

Zien’s character was introduced only in 2022 “after Warren Carlyle came on board as a workshop director,” he said. “That’s what the workshop was basically all about, to see if the device of having an elder narrator threading in and out of the action worked.”

Carlyle, who was already a creative collaborator of Zien’s dancer/choreographer spouse Susan Pilarre on a New York City Center “Encores” show, knew just the guy for the job. And Manilow was instantly on board. “When we first chatted by phone, Barry let me know right off that he’d enjoyed my work in multiple shows,” Zien said. “My mind was blown.” He had the same feeling again when struggling with radical tempo shifts on some material and Manilow graced him “with a private recording of all my parts. Him singing it through, just for me.”

The workshop morphed into an intimate downtown New York showcase production in the 350-seat theater of the Museum of Jewish Heritage that ran from March through May 2022 and was very well received by critics. That paved the way for a larger-scale, $15 million Broadway rendering, which opened last November (after a month of previews)—to a decidedly mixed bag of notices, though Zien consistently reaped praise. The New York Post and Chicago Tribune reviewers were positive, with the latter’s Chris Jones calling it “an emotionally powerful musical of the greatest import.” The website New York Stage Review gave it five stars, while Deadline called it “stirring and compelling.” But reviews in the almighty New York Times and Washington Post were just so-so. The Times’ Jesse Green admired the music but groused about underdeveloped characters (not every Harmonist gets equal treatment). And he seemed to be expressing fatigue from an abundance of Jewish-themed stage productions—maybe because the critic had just finished a huge magazine piece on the subject for the Sunday Times?

“Jesse didn’t really grasp what our show was about,” Zien shrugged. “‘Too much hope and not enough fear,’ as our historic consultant put it. And it’s a musical with a brilliant, period-appropriate, new score, written, to many people’s surprise, by Barry Manilow. Actors usually have a fair assessment of the show they’re in. I’ve been in poorly reviewed shows before, but this time [with Green’s notice], I was completely taken by surprise.”

In the show rewrite, Zien’s Rabbi functions dramatically as the Harmonists’ most fervent celebrant and guilt-stricken conscience whose “‘punishment is to never forget.’ Not really a stretch given my heritage,” mused this mensch of an actor. His ruthlessly bitter, remorseful, vocally taxing 11 o’clock number “Threnody” was especially gut-wrenching, literally stopped the show, and left theatergoers in tears, leading more than one reviewer to compare the moment to the iconic “Rose’s Turn” from Gypsy.

A Life in the Lights

An actor’s life is not for the faint of heart, Chip Zien counsels. In a world where flops greatly outnumber hits and the competition for parts is fierce, “you need a thick skin, an even temper. Connections help—you need to meet the right people—and there’s also a large element of luck. I’ve managed to survive when better actors have not.”

Zien heaps extra praise on his supportive spouse, Susan Pilarre—a longtime (now retired) New York City Ballet dancer, instructor, and re-stager of George Balanchine classics—for broadening his purview and always endorsing his bicoastal work choices, certainly stress-inducing as they’ve raised two daughters. The couple have been together since 1971, meeting just months after his arrival in New York.

It may be a key to his professional longevity that Zien clearly loves the work, the sense of adventure and discovery in the creative process, and the temporary family he gets to embrace in a production. “There are 16 Broadway first-timers in Harmony to tell my stories to,” he shared with bemusement. “Even when a show is lacking, the camaraderie isn’t … Chitty Chitty Bang Bang [which had an eight-month run on Broadway in 2005] “was not the kind of intimate, boutiquey, sung-through musical I normally gravitate to. The flying car was the star,” said Zien, who had a supporting role as a bumbling spy. “But backstage was such fun, a circus every night.”

“It may sound odd,” Zien added, “but the most comfortable and alive I feel all day is under the lights, especially on stage, less so in front of a camera. To me, that’s a wonderful place to be, a safe space. I know the lines yet don’t know what’s coming. I’m dependent on others. We’re all in this emotional moment, on this journey. It brings out my best, truest self.”

His Penn Station

Before he got seriously down to business with acting and singing coaches, started scoring some decent (initially off-Broadway) parts, and could quit his day job selling shoes, Zien “had fears, nightmares that I’d peaked at Penn,” he confided.

For certain, those undergraduate years were ultra-supportive ones for the younger him, officially known to the University registrar as Jerome Herbert Zien though answering to any and all as “Chip,” a nickname first laid on him by his dad. No one at the Daily Pennsylvanian ever wrote that he was “a miserable excuse for Jimmy Durante,” as the acerbic New York magazine critic John Simon would when Zien made his Broadway debut at 27 in a one-night-disaster of a Samurai musical (no joke) called Ride the Winds in 1974.

“Mr. Simon also wrote the best thing about the show was the dog that barked on cue,” Zien said with a laugh. “Danny DeVito was smart enough to walk away after the production’s first table reading. I was not.”

While small in stature like DeVito (“then five-six, lately shrinking”), Zien was a big man on campus. He had a leadership role on the Houston Hall Board, which booked and welcomed Spring Fling/Palestra acts Simon & Garfunkel and the Supremes, and was also a member of the Sphinx Senior Society and Phi Epsilon Pi fraternity. A studious history major, his initial post-Penn game plan called for “law school then maybe something government related.” Back home in Milwaukee just after graduation, Zien “ran a Congressional campaign. My guy lost by half-a-percentage point. If he’d won, I’d probably have followed and worked with him in Washington, done Georgetown Law School at night, and my life would have turned out totally different.”

But first in his heart during his time at Penn was Zien’s “ever-joyful” four-year participation in the famed musical comedy troupe Mask and Wig, which culminated in a starring role in The Devil to Pay and his election as the club’s chairman in his senior year. “I was the first Jewish guy ever elected to the post, in a time when I still couldn’t step foot on the Locust Walk front porches of the Saint E’s [Elmo] or Saint A’s [Anthony] fraternity houses, though a lot of those frat guys were in Mask and Wig, too.” (While chairman, Zien was also an early proponent of making Mask and Wig coed, as he wrote in a letter to the editor following the group’s decision to accept all genders starting with the 2022–23 academic year [“Gazetteer,” Jan|Feb 2022].)

Longtime Mask and Wig coproducer and historian Steve Goff C’62 remembers that Zien had special star power “even in the freshman show” and was so good in his senior show “we took the production on tour all the way to California for the first time ever. Until then, we’d never gone further west than Chicago.”

Zien’s college pal Susan Schwartz Goodrich CW’69 recalls taking a bunch of girlfriends to Mask and Wig, “and when Chip sang a romantic song called ‘A String of Pearls’ they all swooned, were begging me for an introduction, all wanted to date him.”

This writer was a fan and minor league rival, too. As codirector and performer in “The Underground,” an alternative comedy revue in the Catacombs Coffee House (in the back-end basement of the Christian Association), I secretly wished Chip would jump ship and join our little pirate brigade. Fat chance.

“I loved everything about the Mask and Wig,” Zien recalled. “Our own little Center City clubhouse at 310 South Quince, dressing up every night in tuxedos, meeting the alums who came to see us, hanging out around the piano after the show, having a drink or snack.” The kidder sometimes fooled with the Old Guard alumni by introducing himself as “Weightman Hall, Jr.”

Another good friend and castmate, William (then Billy) Kuhn W’69, remembers how, “after the curtain came down, the show just kept going for Chip—entertaining the rest of us cast members with Broadway songs from My Fair Lady and Annie Get Your Gun.” Attuned and sympathetic to how Zien was being pulled in multiple directions, Kuhn would later make a radical career change himself, quitting the family retail business to enroll in rabbinical college in his thirties, eventually becoming Senior Rabbi of Congregation Rodeph Shalom in Philadelphia. “So now I’ve been able to tell Chip how proud I am of him for finally becoming a rabbi, too,” he jokes.

“Chip was and is a trailblazer in a lot of ways,” Kuhn adds. “Mask and Wig had a lot of talented people but no one else up to Chip’s level. Such a positive, upbeat guy. Extremely witty, with a dry sense of humor, but also capable of being quite serious, an outstanding person with a lot of depth. You can see it in the range of roles he’s taken on.”

There were, however, challenges amid the acclaim at Penn. Sophomore year was an especially gloomy one for Zien, when his mother and chief cheerleader Phyllis Zien succumbed to the rare, paralyzing disease polymyositis on March 20, 1967—which was her son’s 20th birthday.

Merrily He Rolled Along

As revealed in his one-man (plus band) cabaret show Seriously Upbeat—also available for your listening pleasure on music streaming services—Zien hardly fell into Mask and Wig by happenstance. He was virtually born with a song in his heart and microphone in his hands. And in his Penn years the guy “secretly harbored” dreams of a mixed bag career “as a nightclub singer/lawyer” who played the Copa and argued cases before the Supreme Court “in the offseason.”

As a single digit tyke, Zien first caught the showbiz bug from his big sister Barbara’s Broadway cast albums, memorizing entire scores and singing along in a sweet soprano voice that got his mom Phyllis thinking “this could be a good outlet” for her small, then “hobby-less” child. Becoming “as much of a stage mom as you could be in Milwaukee,” cracked Zien, Phyllis signed him up at age six to perform on a local TV show—the Tiny Tots Talent Contest—where the kid knocked ’em dead singing a cowboy song, decked out in full Western regalia and shooting off cap pistols at song’s end. “My prize was a giant bag of potato chips. When the host asked what I’d do with them, I said I’d eat them for breakfast because my mom never gets up to feed me. That was a lie, but it got a big laugh—which really pumped me up and taught me that sometimes fibbing is a good thing.”

Next big stop: his summer stage debut at age nine as the half-Polynesian Jerome (a fit made even better with mom’s application of bronzer!) in Milwaukee’s Melody Top theater-in-the-round production of South Pacific. “My big number was ‘Dites-mois.’ The show director suggested that if I moved to New York, I could get work, and my mom said, ‘Chip, do you want to go?’—which I emphatically didn’t. I yelled ‘Mom, are you trying to give me away?’”

Still the stage nurturing continued. His parents—dad Allen was a heating and AC contractor “with a great sense of humor,” Zien said—sent Chip off to a boys-only overnight summer camp where there was always a big musical production. His still pre-pubescent singing voice brought him lead roles he didn’t totally relish—Eliza in My Fair Lady, Lola in Damn Yankees, Annie in Annie Get Your Gun. It took a temper tantrum over the typecasting by Zien, and his mother’s intercession with the camp director, for him to finally be given a male lead, as Howard Hill in The Music Man.

So when Zien landed at Penn, the notion of playing female roles in Mask and Wig revues was not a totally foreign concept for him. But “Chip was too good to waste on that kitschy stuff,” said Bill Kuhn. And Steve Goff “can’t remember him ever being” in the traditional show-closing “female” kickline.

Curiously, when the new rewrite of Harmony first tried out downtown, Zien’s surprise cameos included a wickedly funny Marlene Dietrich impression. (Historically, the Harmonists got a big break backing her up).

Alas, when I saw the show again on Broadway 18 months later, the Dietrich shtick was gone. “The bit got yanked four days before the first preview,” said Zien, whose other cameos included Albert Einstein and Richard Strauss. “Marlene was my favorite,” he added, “but the producer decided to cut it for what I’d call ‘political reasons.’ There had been some complaints downtown that this was an inappropriate thing for me to be doing. There were fears this could come back to haunt us.”

Off and Running

Three law schools admitted Zien. But in the heat of the Vietnam War, Uncle Sam wanted him too. So after running that Congressional campaign, he signed up to teach sixth grade in Milwaukee (a draft-deferrable gig) and started studying for a teaching degree. Then he ended up with a draft lottery number high enough to permanently keep him out of the Army’s clutches. After one teaching year he felt free to take up an interesting offer from a stepsister, also theatrically inclined, who was directing a company of recent University of Wisconsin grads at a “kind of dinner theater” playhouse outside Chicago. She wondered if Zien could substitute for an ailing actor as the lead character Little Chap in Leslie Bricusse and Anthony Newley’s intimate musical Stop the World: I Want to Get Off. Zien went, killed it with the show’s most-famous number, “What Kind of Fool Am I?” and then …

“One night we went out to eat, came back to the theater and discovered it engulfed in flames,” he said. “Everyone had been living there and lost everything but our two cars. Half the cast drove to California to try their luck and were never heard from again. I went with the other half to New York City, started borrowing couches from old Penn pals and looking for work.”

Soon after, Zien fatefully managed to crash an audition for You’re A Good Man, Charlie Brown that “was supposed to be just an Equity call-back” for previously screened Actors’ Equity-card carrying actors. “I claimed there was some misunderstanding and they let me audition.” He scored the role of Snoopy for a production at Ford’s Theater in Washington, wangled his Actors’ Equity Card in the process, and was off and running in the wonderful world of professional show business. “I continued to put off law school. Finally, after four years, the last school I was still dangling, Wisconsin, sent me a letter: ‘Mr. Zien, We’re beginning to doubt your sincerity in attending. Either come now or drop out.’ So I chose the latter.”

A Lifetime of Great Stories

One of Zien’s Harmony costars, Julie Benko—who played Ruth Stern, the Jewish wife of a non-Jewish Comedian Harmonist, in the show, and also starred as Fanny Brice during the recent revival of Funny Girl—said working with him has been “one of the greatest experiences” in her life. “He’s such a brilliant actor,” Benko said. “He’s so funny but then he just rips your heart out. … To watch him and learn from him and collaborate with him has been the gift of a lifetime.”

Zien has lots to share offstage as well as on. Even disasters have their bright side, he believes.

The guy still gets giggly over the night at Into the Woods when “the smoke machine wouldn’t quit, and the entire theater had to be evacuated.”

Or his scary first night as a cast replacement in Les Misérables, when Zien called another character by the wrong name “and no one would help me out of the predicament. There were ‘dead’ characters lying on the stage, shaking with stifled laughter.”

After a chance 1974 encounter near Bloomingdale’s—where it turned out their ballet dancer wives knew each other—Dustin Hoffman offered a then-new-on-the-scene Zien a great learning experience as a dramatic actor, understudying several roles (and briefly touring) in a show Hoffman was directing called All Over Town. “When we were first introduced, Dustin asked me what I did and I sheepishly said, ‘I work nights.’ I couldn’t bring myself to say I was an actor.”

When he was cast as a nervous, irascible film producer in an all-star 2008 revival of Clifford Odets’ The Country Girl, director Mike Nichols gave Zien some practical advice: “Just vary your delivery from slow to fast, soft to loud and you’ve got the makings of a great performance.”

Zien was reluctant to step into the role of tap-dancing (and terminally ill) bookkeeper Otto Kringelein in the musical version of Grand Hotel but loved every night of his two-year stint in 1990–92. He credits staging master Tommy Tune “for coming up with moves that let me pass for a dancer, though my wife would dispute that achievement.”

Screen Gems (and Rhinestones)

While mock-bemoaning that no one’s ever let him “play tall”—maybe code for being a leading man—Zien has long been in demand as a utility player in TV and film roles that call for brash (or quiet) authority, comic cynicism, high anxiety, or all the above—often with a hearty dose of Jewish ethnocentricity.

“When I finished my last indie film Simchas and Sorrows” in 2022, in which he played the devout father of a son about to take a gentile wife, Zien said, “I swore to myself I wasn’t going to take any more elderly Jewish guy roles. Then Harmony came along and how could I turn this down?”

On the small screen, his favorite gig was as a glib, neurotic, chauvinistic scriptwriter on the mid-1990s CBS sitcom Almost Perfect. Premised on a female-led creative team writing a TV cop show, the comedy died a premature death halfway through the second season after network interference caused the show’s high ratings to plummet, he said. Zien also played a hard-bitten DA on Cagney & Lacey made-for-TV movies, a slick ad agency exec on NBC’s Love, Sidney, and a noxious gossip columnist on the daytime soap opera All My Children, among many other TV roles.

On the big screen Zien exuded confidence as the president’s chief of staff (and relished shooting scenes with Denzel Washington) in The Siege (1998), and that same year played a pugnacious sports agent helping cover up a major military/industry scandal in Brian DePalma’s Snake Eyes, going nose-to-nose with crime investigator Nicholas Cage. “I thought I was on a film career roll then,” he said, “but for some reason the train stopped.”

Zien didn’t actually appear in his most infamous film role, as the voice of the titular Howard the Duck in the rare George Lucas/Marvel movie flop of 1986. “A casting director came backstage to the La Jolla Playhouse where I was doing the first revised version of Merrily We Roll Along,” Zien recalled. “She said I had a voice that could pass for a duck, and would I like to audition to be the voice of Howard. Initially I was offended, then found out everyone in town was vying for the part.” Zien initially lost out to Robin Williams, but the comedian/actor quit after a few frustrating days on the job and Zien got the call back.

“My first few days, I didn’t really think it was good either,” he said. And there was no way to fix the dry, often humorless dialogue, as the animated duck’s mouth moves had already been filmed. But he “eventually convinced myself it was the greatest thing ever,” he said, “what I now diagnose as my Howard the Duck Syndrome.”

The critics were cruel, the public stayed away in droves, “but decades later the movie became a cult hit with a new generation of 12-year-old Marvel comic fans. And the fat paycheck from Lucasfilm covered the down payment for a ‘classic six,’” Zien said, referring to the Upper West Side apartment he has shared ever since with Susan and their two now grown daughters.

Zien’s film career has also suffered from having some of his “best parts” left on the cutting room floor. In the 2006 9/11 docudrama United 93, you’ll find him pivotal to the plot but with virtually no dialogue as the passenger in first-class whose throat is cut by a terrorist.

In a decorative but flimsy 1994 flick about Dorothy Parker and the Algonquin Roundtable, Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle, Zien played powerful newspaper columnist Franklin P. Adams. But in the final edit he was mostly reduced to looking dapper, smoking a cigar. “The director Alan Rudolph came up to me before the first screening and confided, ‘Several actors are going to be very upset tonight because their parts have been slashed to the bone.’ I foolishly presumed he wasn’t talking about me!”

While the dark film comedy about elderly people seeking euthanasia, Grace Quigley, proved no laughing matter to critics, Zien (who played a psychiatrist) loved hanging out with its stars Nick Nolte and Katharine Hepburn—especially watching and learning from Hepburn in what would be her penultimate screen role. “After one take, the director said to her, ‘That was a little fancy.’ So the next take, she made her performance smaller and more simple and more powerful. I’m still working on doing that.”

Zien also had private time with the Hollywood legend. “Kate insisted on meeting anyone she was doing scenes with, so I was invited to her New York brownstone,” he recalled. “We went into the garden—this amazing inner courtyard shared by the whole block of townhouses, like walking back into 1938. She said, ‘Do you know who my neighbor is? His name is Stephen Sondheim, and he’s a horrible person because he plays his piano at three in the morning. One night I climbed his rose trellis and pounded on the glass and shouted, ‘Stop playing!”’

Not long after, Zien got to visit Sondheim’s residence to go over material, again found himself in the shared courtyard, and asked the question in reverse, pointing to Hepburn’s place: “Do you know who lives there?”

“‘It’s the witch next door!’ Steve bellowed. That line later worked itself into Into the Woods, uttered by my wonderful stage partner Joanna Gleason,” Zien said.

Coda

“Closing shows is really complicated. Every time is a little different. This one really hurts,” Zien shared, shortly after producers sprung the February 4 closing on the Harmony cast.

Just a few weeks prior the money guys had predicted the run would last “until the Tony Awards”—and then hopefully get a big sales bump from their show exposure and victories. The Harmony score is likewise a strong Tony candidate. “I hate the whole ‘nomination disease’ that infiltrates every production at every level,” Zien grumbled. “On the other hand, I’d really like to win.”

Hindsight is 20/20. But what if Harmony had followed the popular practice of opening in the spring to be closer to the Tonys? Could they have advertised it differently? “Many people believed they were coming to see a show about a BOY BAND singing Barry Manilow songs,” ruminated Zien in a late-night email (because he was trying to save his voice for the final performances). “It was a conscious decision to push that simple idea to the exclusion of so many deeper issues.”

On the upside, Zien has now established himself as a mature persona who can carry a show on his shoulders, though he modestly characterizes it as a team effort. And what’s next “is always a pleasant possibility. I’m not retiring … though being 76 does make it harder. Harder to maintain your body, harder to maintain your voice. I wonder, how many shows can I do? Might this be it?”

Tony Randall once counseled Zien that, “If, in an entire career you get a couple Broadway shows, maybe three, where you get to introduce a really great role, consider yourself lucky.”

With Mendel, the Baker, and now Rabbi, Chip Zien has clearly been there, done that.

Jonathan Takiff C’68 is a longtime entertainment reporter/critic.

A Zien Sampler

Want to belatedly catch up on Chip Zien’s career? A video recording of Harmony is available for free, in-person viewing at the New York Public Library For the Performing Arts’ Theatre and Film Archive at Lincoln Center (nypl.org/locations/lpa/theatre-film-and-tape-archive). The original 1987 stage production of Into the Woods is ready for renting on the streaming sites BroadwayHD, Prime Video, and Vudu Fandango.

Almost Perfect episodes are available on YouTube. Zien’s “Cagney and Lacey” made-for-TV movie turn—True Convictions and The View Through the Glass Ceiling—are on free, ad-supported streaming services including Tubi and Roku Channel. His feature film appearances are all accessible on pay-per-view streaming services. —JT

We at Mask & Wig are proud to call Chip a member!

– Peter Kohn C’89

Historian, Mask & Wig Club

Exuberant, exhilarating and epic article. Thank you!

Great interview Chip!