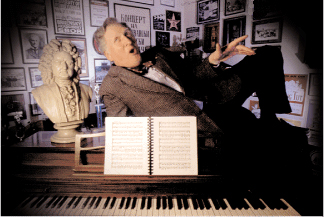

Bruce Montgomery is laying down his baton after half a century at Penn. In a spirited interview, he talks about his musical triumphs, tribulations and travels.

By Samuel Hughes | Photography by Candace diCarlo

The Zellerbach Theatre of the Annenberg Center. The curtain is up, and backstage, a mess of props and wires is visible to the audience. A ghostlight plays on the stage. From the downstage pit rows, the orchestra strikes up the overture.

Suddenly a door to an upstage hallway flies open; a bright light streaks across the stage; and there, in silhouette, is the handsome, vital visage of Bruce Montgomery. A thunderous applause mixed with shouts and cheers greets him; it is a good two minutes before he can speak. He walks on into pools of light.

Monty: Wow! Is this really how it all happened, how it all started 50 years ago?

He walks into the next light and begins to sing, to the tune of “All I Need Is the Girl”:

Got my tweeds pressed,

Got my best vest,

All I need now is a club …”

—From The Fool Monty, written and directed by Bruce Montgomery, performed in February 2000.

For those who have never spent any time with Bruce Montgomery—and until recently, I was one of them —it may be hard to grasp just what a remarkable soul the University is losing to retirement. At first blush, the very idea of a Philadelphia blue-blood who goes by “Monty” directing blazered young men in songs like “Hail Pennsylvania” and “Bury Me Out on the Lone Prairie”—not to mention all those Gilbert & Sullivan operettas with the Penn Singers—may seem too retro for words. That he has been doing so for more than four decades might be chalked up to good genes and tenacity, until you think about it a little—at which point you realize that glee clubs around the country have been dying off in droves since the sixties. Keeping the program not just alive but thriving into the new millennium could only have been pulled off by someone with extraordinary passion, vitality and flair.

Since 1959, when he first took the Glee Club on the road, they have traveled to some 30 countries on five continents, spreading the gospel of song. Their adventures have ranged from harrowing to hilarious to almost unbearably moving. Throughout, he has practiced what might be described as sing-song diplomacy, winning over hearts, minds and news media.

Example: In 1989, when a mob celebrating the overthrow of the pro-American Papandreou regime descended, loudly and somewhat menacingly, upon the Glee Club in Syntagma Square, Monty had his singers break into the Greek national anthem, followed by a Greek folk song. The next day, an Athens newspaper, Apogevmatini, suggested on its front page that the United States government “would be very wise to try a 10-year experiment of doing away with all professional diplomats and sending the Penn Glee Club on tour.” (For more travel stories, keep reading.)

At Penn, his irresistible showmanship has been anchored by a profound attachment to his students, who have become a kind of extended family for him. They, in turn, regard him as somewhere between a delightful deity and a theatrical Mr. Chips.

But even the best shows stop running eventually, and on June 1—half a century after he began at Penn, five weeks after the Glee Club Graduate Club’s emotional farewell concert at the Zellerbach, and 10 days after his final Commencement—the man they call Monty will retire. (During Commencement, the Glee Club will once again sing his “Academic Festive Anthem,” which features his music and Benjamin Franklin’s words.) Sometime after he steps down, the University is expected to name his successor. But no one can really replace him.

Bruce Eglinton Montgomery: The name is layered with culture and social distinction. Eglinton is the Montgomery family’s ancestral home in Scotland, and its magnificent ruined castle inspired him to pen an eponymous work for the Concerto Soloists Chamber Orchestra. One of his cousins is Robert Montgomery Scott, former president of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Monty was born with a silver pitch pipe in his mouth. Both parents were opera singers: His father, James, sang the leading tenor role in virtually every opera in the regular repertoire, as well as all 13 extant works by Gilbert & Sullivan; his mother, Constance, would also have been a professional had she not forgone a career to raise the family. Monty’s earliest memories are of hearing them sing the great operatic duets together, and he acknowledges that for his entire childhood, he was “surrounded” by music.

He wrote his first piece of music when he was five—“The Sea,” so named because he wrote it in Atlantic City—and every Friday afternoon he would be excused from his kindergarten class at Germantown Friends School to hear Leopold Stokowski conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra. That same year, he made his stage debut in the Philadelphia Orchestra Opera Company’s production of Gilbert & Sullivan’s Trial by Jury. (He played a naughty, disruptive child, and still has the blue Kodak camera that he purchased with that first paycheck.)

He was six when he wrote his first operetta, “The King of Arabia,” which included a scene wherein the young hero received a letter from a rival kingdom. “You are invited to a war,” it said. “If you do not accept, you will become lame.” Young Monty of Arabia delivered a ringing denunciation of war; fell to the ground, lame; then, after a silent, kneeling prayer, got up, shook his legs and exclaimed: “Golly, that was quick work!’”

After graduating in 1945 from Germantown Friends—where he had what amounted to private tutoring in music theory, composition, and counterpoint, as well as painting and lithography—he made a last-minute decision to forgo Yale University and its flood of returning soldiers. Instead, he spent four blissful years at Bethany College in Kansas, studying music composition and sculpture and painting. (Later this month, he will deliver Bethany’s Commencement address and receive an honorary degree.)

In 1950, his father founded the Gilbert & Sullivan Players—“which, in its day, was one of the best and most famous companies in America, because they did the real thing. They didn’t hokey it up at all.” James Montgomery directed the company for five years—then, on the opening night of Patience, suffered a fatal heart attack. His dying words to his son—who was playing the role of poet Archibald Grosvenor—were, incredibly: “The show goes on.”

That it did. Monty was thrown into the breach of directing while “trying to be funny” as the Idyllic Poet, even as he grappled with his father’s death. “That was a little rough,” he allows.

By then he had already begun his half-century career at Penn as assistant director of the Cultural Olympics—a “terrible name for a very good program” that featured dance, drama, painting and music. When the program was terminated in 1955, he put in a year’s stint as assistant to Donald T. Sheehan, Penn’s first director of public relations, before being asked by then-president Gaylord Harnwell if he would take over the University’s extracurricular musical activities. His response: “Of course!”

It hasn’t all been song, dance and klieg lights. In 1951, he was drafted and sent to Korea. “I don’t usually talk too much about my Korean experience,” he says quietly. “I was in the 45th infantry division; I fought hard; I was a good soldier. The scariest day of my entire life was my 25th birthday, as I waded ashore at Inchon, with bullets going all around. The water was still cold, but it was warm around me—I was very scared.” He had several horrible experiences, including one in which he was “literally buried alive for about 30 hours with a dead guy” in his arms, not knowing whether he would ever be found. He still wakes up at night screaming Get me out!

But while Monty is not one to duck questions or stifle emotion, he is hardly the sort to dwell on unpleasantness. He alchemized his loathing of war into Why Me?, his 1967 musical set in the Korean War, and Herodotus Fragments, written for a full symphony orchestra and two choruses, which the Philadelphia Orchestra premiered in 1970. (That piece was directly inspired by a visit to the pass at Thermopylae, where in his mind’s eye he could still see Xerxes’ arrows blocking out the sun, and where a stele still read: Stranger, go tell the Spartans we lie here, obeying their laws.) And now, winding up a resplendent career at Penn, he is brimming with plans to travel and compose and paint—the latter activities, as always, to be carried out on his private island off the coast of Maine.

Back in February, we sat down in the living room next to the Faculty Club (where one of his Maine watercolors hangs), and for two hours Monty—wearing a creamy tweed jacket, green vest and bow tie—showed his mettle as a raconteur. The imaginative passion that he brought to his recollections was astonishing. On several occasions he found himself on the verge of tears, a sentiment that was as catching as his ebullient humor. What follows is an edited version of that conversation.

Gazette: What other musical activities besides the Glee Club were going on when you began?

Monty: Nothing like what there is today. At that time, about 400 members of the freshman class would line up on the Schuylkill River and go into a great phalanx across the campus, trying out for everything. I would always audition three or four hundred people for a relatively few slots in the Glee Club. Nowadays, there are, I think, 36 extracurricular musical organizations—which is astonishing—and many of them were started by Glee Club people. I directed Mask & Wig for years, and I worked with a number of the smaller a-cappella groups and arranged things for some of them. And I’ve been musical director of Penn Players and stage director for Penn Players for a number of their productions. So I’ve kept my finger in a lot of pies. Fortunately, I was one of those first-cousin kids, so I have 14 fingers.

At that time, I also did the band—I was probably the worst band director that ever worked on Franklin Field. Penn Singers [née Pennsyngers] was just getting started as a female chorus, and they found that they sort of outnumbered their audiences every time they performed—there really wasn’t a great demand for it here. So I got rid of their director and took it over myself and turned it into a co-ed chorus.

The very first program I think I ever conducted of theirs we called “Three Ages of Faith.” The first half was early music by Buxtehude, a Schubert Mass and nine movements from the then-popular Jesus Christ Superstar, complete with rock band. After the intermission we did the one short Gilbert & Sullivan show, Trial by Jury, and we sold out before we opened. The following Tuesday was our next rehearsal, and I said, “OK—you’ve done romantic music; you’ve done contemporary stuff; and you’ve done light opera. Which direction do you want to go?” And they all said, “Light opera.” So we did Gilbert & Sullivan every spring from that moment on.

Gazette: But you don’t monkey with the script.

Monty: No. Never. The closest I ever came to that was in, I think it was 1972. We did Patience in the Zellerbach. This is a show that literally laughed the Pre-Raphaelite movement out of existence. Really—the aestheticism of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, and the affectations attendant thereto, were absolute parallels to the flower children of the late sixties and early seventies, and Oscar Wilde and Algernon Swinburne and people like that were the [Allen] Ginsburgs and the others. And so, just for fun—I didn’t change one note or one syllable, but we did Patience with the two poets wearing pink turtlenecks and pink jeans and sitting on a ladder with an electric guitar. And—again, not changing a single syllable—the women were the flower children of the 1960s and early 1970s.

There’s a transformation at the end wherein Grosvenor realizes that this is a ridiculous affectation, so he and his women followers go through a complete change. And I brought all the women in in mini-skirts with high white-plastic boots and clear plastic umbrellas; we brought in a huge rolled-up Union Jack, which unrolled all the way down to the footlights; and in came Grosvenor in a leather jacket with studs all over it and Wellingtons with a British Flag painted on the front—and it was absolutely as appropriate as the day Gilbert & Sullivan wrote the opera. It was astonishing.

Gazette: With the Glee Club, you’ve been described as someone who “takes ordinary young men and molds them into an extraordinary program.”

Monty: I appreciate that comment. There certainly has never, in the history of this University, been anyone who has enjoyed working with extraordinary people the way I have. And yes, they all pass an audition vocally to get in, but they end up being the most remarkable young men I can possibly imagine working with. And that was true, believe it or not, during the late sixties and early seventies, when it was the time of “Do your own thing,” and joining an organized group was taboo, verboten. And they continued to join, and we continued to do, I think, meaningful statements on the conditions of the world, on the Vietnam War, on prison riots, on pollution, on whatever—and remained viable that way. So we never suffered the slump that other choruses around the country did—glee clubs were rolling over like dinosaurs and dying, literally by the hundreds. I was on the board of the Intercollegiate Musical Council for years, and that was made up of the directors of all the male choruses in the country, and it got to the point where there just weren’t many left—enough of an attrition where we terminated the program. The IMC doesn’t meet anymore.

Gazette: Beyond tradition, what is the appeal of an all-male glee club?

Monty: The sound. It’s absolutely unique. For years, earlier in the women’s lib movement, I would get a visit every year from the new head. And we would always chat amicably, and I would mention that it’s perfectly possible for a fine tuba player to wish to play with the Budapest String Quartet. It can be done, but it certainly changes the sound. And there’s something very special about the Budapest String Quartet, or the Juilliard String Quartet or the Curtis String Quartet. There’s something very special about the sound and the repertoire of a male chorus. And we already have a bunch of other mixed choruses; why destroy one just to be P.C.?

Gazette: Tell me about some of the early tours with the Glee Club.

Monty: Well, before me, there were no tours. And in 1959, the alumni were meeting in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Leonard Dill [C’56] was the head of the Alumni Society, and I went to Len and said, ‘Wouldn’t it be interesting if the Glee Club were to show up in Puerto Rico, and sing for your final banquet?’—which coincided with our spring vacation. So he thought this was a wonderful idea, and I got all sorts of assurances that the Alumni Society would help, and the University would help underwrite the thing, and all this was going to be fine. We rented white dinner jackets for everyone in the club, instead of the black with which we normally sang at that time, and we went down and stayed at a hotel very near where the alumni were meeting. And it turned out that nobody picked up any tabs, so I ended up paying for the entire Glee Club to go there, to stay there, and to come back. And it was the best investment I ever made. It absolutely clinched the Glee Club and its self-esteem and popularity with the alumni.

We had wonderful experiences, including doing a television show in San Juan on the state-owned station, and just before leaving the station, there was a message on the loudspeaker system that there was a telephone call for me, in the engineer’s booth; I went in there, and it was Pablo Casals, at that time probably the greatest cellist in the world. He lived in Puerto Rico, and he said, “What are you doing tomorrow morning?” And he invited the entire Glee Club out to his home. We made music together, and he and his wife gave us lunch, and it was a wonderful experience.

The most exhausting trip we ever took included Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Soviet Union, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia and England. And we were gone for close to five weeks—that’s too long for any collegiate tour.

As soon as we arrived in Leningrad, now St. Petersburg, we were introduced to Zoya, the gal who was going to be with us every waking moment of our lives there. Zoya had taken Harrison Salisbury around when he was writing the book, The 900 Days, about the siege of Leningrad during World War II. We got along beautifully, but she was very unmoving about one subject. I told her how everywhere—in Ecuador, in Peru, in London—if we’d see a crowd, we’d stop and sing on a street corner, in a schoolyard for kids, workers in a park, whatever. [He assumes a Russian accent] “Not in Soviet Union.” She was very adamant about that. We sing exactly where we are told to sing, and no other places.

On about our third or fourth day in Leningrad, we had a free morning, and we went out to the Piskariovskoye Cemetery. It’s a war cemetery; it has mounds that stretch almost as far as the eye can see, and they claim that under every mound are 40,000 bodies. These are people who did not survive, civilians and military. And just as you enter this cemetery, there’s a plaza with a sunken pit, and in it is the eternal flame, and she said, “When we come here, we observe a minute of silence at the eternal flame before going down the steps to the cemetery proper. Would you care to join us?”

We did. Incidentally, Zoya had lost her entire family during World War II. She survived by eating sawdust and rats, but the rest of her family was wiped out completely. So she was very anxious that we see this cemetery; it meant a great deal to her. So we ringed the eternal flame, and I was standing next to Zoya, and after a minute or so, I said to her very quietly, “In 1963, NBC hired me to make a [choral] setting of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, to be filmed on the battlefield at Gettysburg, which is, of course, a war battlefield also. And it had been received very well by everyone; may we show our respects by going to those steps that lead down into the cemetery, and sing that?”

And she thought for a minute, and she said, “I think that would be appropriate.”

So we went to the steps, and within a few measures, there were some people stopping to listen. And in a few more measures there were 100 people. And then there were 500 people. And then there were 1,000 people—probably not one of whom understood what we were singing, but they sure knew the intent. And our guys would have tears in their eyes—I’m getting misty just thinking about it, I’m sorry—our guys would have tears streaming down our cheeks. There were a couple of guys who sat down on the steps—they couldn’t even sing anymore, they were so moved by the emotion of this moment.

And after we finished that, we got back on the bus. Zoya had been with this robust, rowdy bunch of guys for three days, and it was a trip back to Leningrad in utter silence. She was very much moved by this, and when we got off the bus at our hotel, I was the last person to get off, and she waited until the last student went by and said: “From now on, you sing wherever you wish.”

In Primorsko, Bulgaria, we were swimming in the Black Sea, and we were playing with frisbees on the beach. I always bring about a hundred frisbees with us to any foreign countries we go to and leave them behind, and they have a little thing silk-screened on them: Gift from the University of Pennsylvania Glee Club, Philadelphia, Pa., USA. And we got them involved, and one of the Bulgarian students, in rather halting English, said, “Are you here for the tournament?” and we had no idea what tournament he was talking about. And it turned out to be an international, open basketball tournament. So we put together a basketball team on the shores of the Black Sea, and entered the tournament. And I don’t remember the actual statistics, but the Penn Glee Club beat, we’ll say, three East German teams, a couple of Russian teams, five or six Bulgarian teams, a Yugoslavian team, and we came in third! And I have a photograph of the three tiers as you find in the Olympics, with Terry Tucker [C’74] standing there with a garland of flowers and holding a medallion for the basketball tournament, which I have framed on the wall of my office.

As a result of that, our last night was a concert in an open-air theater that was supposed to hold about 2,000 people. Well, according to the Voice of America, there were 3,000 people who jammed themselves into it. And afterwards, a group of Bulgarian students came to me with an interpreter, and said, “Some of us came here tonight to spoil your concert with shouts of ‘Vietnam.’ But we saw nothing but love. We will talk of Vietnam tomorrow.”

Gazette: That’s extraordinary.

Monty: It is extraordinary. And so many experiences like that. I’ll never forget one in Lima, Peru, where we were booed and hissed so that we couldn’t sing. And I immediately changed it to their national anthem, and they shut up, and we sang some Peruvian songs, and we sang on for another hour. And our first secretary of the embassy came up to me afterwards—wearing a tee shirt and blue jeans; he didn’t mind looking American, but he didn’t want to be looking too official—and he said: “As you know, we told you not to come here, but thank God you did. You’ve done more in 24 hours than we’ve done in 24 years.”

You see, I had received a telephone call in Ambato, Ecuador, from our ambassador, saying that he’d taken it upon himself to cancel our tour of Peru because of the anti-American feeling. And they closed the embassy, too. And I said to him on the telephone from Ecuador, “Are you telling me we cannot go? Are you ordering us not to go?” And he said, “No, I can’t order you not to go.” And then I asked, I thought, a very telling question: “Obviously, I cannot take other people’s children’s lives in my hands, so can you assure me that our lives will not be in any greater danger, say, than in West Philadelphia?”—which I thought left him a bit of latitude. And he said, “No, your lives won’t be in danger, but your presence will be the cause of some demonstrations.” And so we thought a little bit, and I called him back from Cuenca, Ecuador, and said, “We’ve decided to come.” And he said, “Well, I won’t say no. The embassy will be closed, but come ahead if you wish.” And then he did a very, very smart thing. He spread the word to the government and to the newspapers that we were defying our government. So consequently, we were heroes from the moment the plane hit the tarmac in Lima. And just before we left Ecuador, our bus was bombed—we weren’t in it, fortunately, at the time. This was 1969; it was a very volatile era. And when we arrived in Lima, we were heroes because of the news he had spread. So the newspapers and television cameras rushed out to the plane, and then they put up a hurriedly called news conference with ropes around it in the airport, and then we were rushed to the state-owned television station, which had sort of their version of Johnny Carson, the most popular program in Peru. They came on singing, and then the club went into a hum for 19 seconds, and for those 19 seconds I turned around and faced the camera and also the large studio audience, and said: “Buenas noches, damas y caballeros. Es un gran placer que el club de cantar de la Universidad de Pennsylvania ha venido para compartir su música y su sincera amistad con sus amigos en Lima. Y ahora, amigos, El Glee Club de la Universidad de Pennsylvania.” I turned around, and the guys burst into lyrics again, and we finished the song, and for the next four or five minutes—live, on camera—I was trying to convince them: “I have memorized 19 seconds worth; I don’t know one more syllable of Spanish.” And a fellow named Juan Arcé, a member of the studio audience, jumped onto the stage and convinced the host that I had memorized this, that I don’t speak Spanish. And of course I could see it back and forth, something like, “But he just did!” and that sort of stuff. And then Juan left his job for the next two weeks and became our interpreter, came with us everywhere we went, and the Peruvian Air Force gave us the best bus in all of Peru, and we had that at our disposal so we wouldn’t miss anything for lack of transportation. And we were all over the place because of that.

Gazette: I gather that one night there, the show almost didn’t go on?

Monty: Oh, that’s another story. In 1987, we went back to Peru, at the request of the wife of the president, Señora García, who asked us to come back and raise money for her favorite charity, which was La Fundación de los Niños—children’s villages of orphaned kids.

We had performances in Trujillo, and between Lima and Trujillo we stopped for lunch in Huanchaco, which is a seaside town. And we all, as one does at a seaside town, had fish—which was all bad. It was horrendous. And every single guy in the Glee Club was sick. And in Trujillo we had two performances, one at 7 and one at 9:30. And you never saw people try so hard to put on a performance when they felt so bad. There would be long moments when I would see two-thirds of the Glee Club on stage, knowing full well that the other third was back there vomiting and with diarrhea, and they were just having a ghastly time. And just toward the end of the first performance I had to vomit, and did something I have never done before and never will again: I swallowed my own vomit rather than spray it all over my orchestra-pit kids.

And during the intermission everyone was lying on the stage backstage, after the curtain had fallen after the first performance, knowing that in another three-quarters of an hour, up it went again. And I’ll never forget Brendan O’Brien [W’88], who was the president at the time—his face looked like it was made of chalk, and he was lying back there and he had the whole club gathered around him, and he said [in a feeble whisper]: “Gentleman, Monty will tell about this to Glee Clubs of the future for decades. Let’s get up, and DO it.” And he struggled to his feet, the whole club struggles to its feet, and on went the second show. And again, we were sick as could be, but everyone was on stage doing this show. And I’ve been talking about it ever since!

Gazette: That’s heroism.

Monty: Yeah, it was heroism. It was absolutely, unbelievably remarkable. Talk about the show must go on.

Gazette: You were in Hungary, too, weren’t you?

Monty: The day we arrived in Budapest was the very day that the first democratically elected president in 42 years took office—that very day. So it was a country of euphoria, and we traveled all over the place, to a very, very receptive audience everywhere. And for one segment, for about a week I guess, we stayed in sort of a summer camp on the south shore of Lake Balaton. And we got to know the kids, and they ranged in age from about maybe eight to 15. And we got to play with all the kids, and they challenged us to soccer; we challenged them to basketball. They always won the soccer games, we always won the basketball games.

And the last night we were there, we came back from a concert around midnight, and they had dug a deep hole and lined it with stone, and had built a big bonfire. And all the kids were sitting all around it, and it was a goodbye party for us. So we sat around with them and then sang—and sang, and sang, and sang. And at the end of it, it was getting sort of late, so I walked over to the soccer coach, who spoke some English and I’d befriended several days earlier, and I suggested that it was getting a little late for some of these kids. So we ended it by singing a Hungarian folk song, and then our national anthem, and then their national anthem. We do that, incidentally, everywhere we go.

After their national anthem was finished, there was a brief pause, and then one little girl, with this high, ethereal soprano voice started singing something. And a little boy joined her. And then someone else joined the two of them. And then it started spreading, and everyone was singing it. I turned to the soccer coach and said, “What is that they’re singing? They started so tentatively, and they all started joining in with great robustness.” He said, “That’s the Transylvanian anthem, which they haven’t been allowed to know existed for 42 years.” And in every family, parents had been passing it down secretly to their kids, and now it was a free democracy, and they were all singing this Transylvanian anthem.

[Emotionally] That was below the belt. Every experience of that sort just knocks me for a loop.

Gazette: What do you see for the future of the Glee Club?

Monty: I wish I could tell you, Sam. This is my major concern about leaving. When one has been here for 50 years, you build up sort of an empire or a domain that is sort of hands-off. I’ve never had anyone breathe down my neck, and I’ve never had a boss to whom I had to report and all that. I’m sure I would have if I hadn’t been

producing, but apparently people have been happy with what I’ve done, so I’ve had a tremendous degree of autonomy. And as a consequence, longevity itself has enhanced the position. My big worry about leaving is: Is my successor going to get the same respect? Is the Glee Club going to be the thing they think about when they want to do a major thing, such as next Thursday [February 24, see “Gazetteer” on page 20] when we sing for the president of the United States? When the Shah of Iran came, it was the Glee Club. When Lech Walesa came, it was the Glee Club. When Lord Louis Mountbatten came, it was the Glee Club. It’s always been thought of for the important occasions to represent the University at its best. My fear is that someone will say, “Well, thank God, we finally got rid of Montgomery, and now we don’t have to think about this all the time.” But I think, and I hope and pray, that my successor, whoever that may be, will be given the same respect by the club as well as by the University; will have the same imagination and the same desire to do the best he possibly can do and to get students to do something beyond their capabilities. It’s like the bumblebee—aerodynamically, a bumblebee can’t fly with that size wing and that size body. But the bumblebee doesn’t know that, so he flies. I think there’s almost nothing you could ask of students of this University that they can’t do if you challenge them to do it. And if my successor will approach the job with that attitude, I’m convinced that it will never sag.

Gazette: Any final thoughts on what the University has meant to you?

Monty: [With wicked amusement] Hmm-hmm—mostly unprintable. No, you know that’s not true! Really, without sounding like Pollyanna or something, the University has been my life, my entire adult life. As I said to Judy Rodin, when I first approached her about this retirement, June 2, 2000, will be the first day of my life in a non-academic atmosphere since kindergarten. Which is astonishing. I’m retiring because I have so many other things I want to do and places to go and things to see, books to write, paintings to paint and sculpture to sculpt—music to write. If I don’t retire, I won’t be able to do these things.

And the one thing I cannot possibly imagine, in my wildest flights of fancy, is how I’m going to miss the kids, how I’m going to miss the students. Because they’re all my kids. They’re all my sons and daughters. And that’s something I dread.

This sounds terrible for someone to say, but I wake up every morning and as I’m shaving, I look in the mirror and say, “You lucky son of a bitch. Wow—I can’t wait to get in and work with students.” And I don’t know many people who are that happy. And it means giving up most nights, virtually all weekends, most vacations except the summer vacation—but I would do it again like that [snaps fingers] if I were 21 and starting all over again, and knew what I had ahead of me.

Gazette: Somehow I don’t think that all those students are going to be gone from your life forever.

Monty: Well, I hear all the time from students that I’ve had for the entire expanse of my time here. But I won’t see the new ones come in every year—the new crop of freshmen that adds so much to my life every year. And as I’ve said so many times, and I mean so sincerely even though it comes out as a line on a sampler: I’ve loved teaching here, but I’ve learned so much more from students than I’ve ever taught them. It’s just astonishing how much I’ve learned from them. And how much I love them. [Whispers] God, I’ve been so fortunate.