By Samuel Hughes

Sidebar | Love Story

Wicked’s witch is taking off: rising up into the stage sky in a shimmering plume of smoke, clutching her broomstick as she belts out her triumphant message to the pursuing Ozian guards below:

To those who ground me,

Take a message back from me!

Tell them how I am defying gravity!!!

I’m flying high defying gravity!!!

It’s a sense-blasting moment, and as the billowing curtain-map of Oz comes down on Act 1, the applause is electric.

The houselights brighten. The audience buzzes and stirs, some heading toward the lobby to buy a Wicked T-shirt or the bound-for-platinum CD. Every one of the Gershwin Theatre’s 1,933 seats has a person in it, as they have had during every performance, day and night, week and weekend. Despite mixed reviews from theater critics, Wicked has been packing them in for better than two years now, and looks as though it will be for years to come.

Wicked “sells like rock salt on the cusp of a blizzard,” noted The Washington Post in December. “The numbers tell a breathtaking success story, of a magnitude the theater has not witnessed since the peak years of The Phantom of the Opera.”

It didn’t just fly into Broadway on a Nimbus 2000. Having begun life as a novel, it reached out a green hand and grabbed the gut-strings of Marc Platt C’79, then president of production for Universal Studios. Through him it mutated into several stillborn film screenplays, until a phone call from composer Stephen Schwartz helped transmogrify it into a musical. Since then it has been revamped and retooled, sucked up $14 million from its investors, won some awards—and earned the fanatical devotion of its audiences. Now it’s a certified Monster.

From my $110 seat in the Gershwin, I’m still transfixed by the curtained stage, which is framed by a series of vine-tangled cogs and wheels. They’re supposed to suggest the political machinations, in a setting of threatening wildness, at work in Oz. But with the houselights on, those outsized cogs could also stand as a symbol of the grinding machinery behind the glitter of Show Business.

“What I love about being a producer is that first comes passion,” Platt is saying. “Now, your passion does have to be informed by intelligent thinking. It does have to be informed by business, by the marketplace, by financial analysis. But I’m lucky that everything I do starts with passion. I get to pursue stories or individuals—talent—that stir my insides. Being in a position to be the facilitator of that—of taking that passion or someone else’s passion and talent and translating it into something that can be shared by the world—is an exhilarating process.”

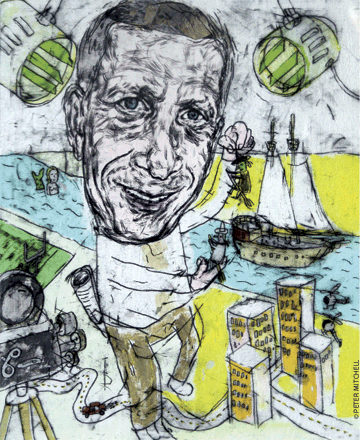

He is sitting in an empty conference room in Marc Platt Productions’ East Coast offices on West 44th Street in Manhattan, talking animatedly about his rather extraordinary life as a show-business producer. He’s dressed casually in jeans and a gray fleece jacket, which goes nicely with his healthy head of short silvery hair. On the table before him are a script, a pencil, and a BlackBerry, which every now and then he checks discreetly.

For a guy who works mostly out of the spotlight, he’s quite at home in an interview. Toss him a question and he’ll answer that one and four or five others on your list without catching his breath. Though he talks quickly, and occasionally karate-chops the table for emphasis, he has his engine under control. Which is a good thing, because that motor clearly revs at a very high speed.

Consider what Marc Platt Productions has going on right now. There’s Wicked, of course, which now has three companies bewitching the nation, and is streaking toward a September opening in London. Also across the pond, a Matthew Bourne ballet production of Edward Scissorhands recently performed to mostly glowing reviews around the United Kingdom, and will open in the U.S. in December. Last month, Richard Greenberg’s Three Days of Rain, starring Platt’s old pal Julia Roberts, opened on Broadway; the entire run sold out before the first performance. Then there is the ABC miniseries about the 9/11 Commission, starring Harvey Keitel, which will air, fittingly, the second week of September. (Platt doesn’t venture into television very often, but a week after our January interview, he was on TV accepting a Golden Globe for Empire Falls, his HBO movie with Ed Harris, Paul Newman, and Joanne Woodward.)

That list doesn’t even touch on the long string of film projects in various stages of development, or the even longer string of smash hits (Legally Blonde, Sleepless in Seattle, Jerry McGuire) and artistic triumphs (The Silence of the Lambs, Dances with Wolves, Philadelphia) he has produced with Marc Platt Productions or, before that, as a top executive with Universal Studios, Tri-Star, and Orion. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

“I often characterize my days as: I get up and I get to work and I run as fast as I can all day long—and about 10 times a day I run smack into a brick wall, and it knocks me down on my rear end,” Platt says. “But every so often when I hit the wall, there’s a door there. And I get to run through the door. It only happens infrequently, but once you run through that door, it’s quite glorious.”

If The Marc Platt Story doesn’t come to your neighborhood multiplex anytime soon, it won’t be because the subject isn’t an engaging and intriguing character, or that he doesn’t have an outstanding supporting cast. He is, and he does. But if you’re looking for a storyline with conflict and crisis, failure and redemption, you’ll have to juice the facts a little. Because the basic arc of Platt’s life so far has been a steady, hard-working, turbo-charged ascent into the Successosphere.

He has always loved telling stories—all kinds of stories, in all manner of media, from a variety of vantage points. As a little boy in Baltimore, and later in high school, he often found himself directing plays—sometimes just neighborhood kids in backyard productions, sometimes on real stages with curtains and sound systems and lights.

“I clearly liked being in charge, so I guess that still remains in my personality,” he says with a laugh. “It sounds silly, I suppose, but a play is a play, whether it’s in your backyard or a high-school stage or in the Quad or on Broadway. When you’re learning in all those environments, it all adds up to helping one become a good storyteller.”

April 1976. Platt, still a freshman, is trying to figure out how to stage a production of Peter Pan, which he is directing in the Quad for the Quadramics. As he walks around the lower Quad, his eyes light on a small courtyard, with little bay windows and porches around it, at the eastern end near 36th Street. A klieg light goes on over his head.

“It had a sort of Victorian, English feel to it,” he recalls, “and it just hit me that I could actually use the structure of the Quad as the set. And when Wendy’s looking at Peter Pan, she actually stood on the porch and looked up at the sky. So I didn’t have to build much of a set.”

That performance of Peter Pan took place during Spring Fling, which must have made for some interesting audience participation, especially since the curtain time was something like 11 p.m.

The character of Mrs. Darling, incidentally, was played by a fellow freshman named Julie Beren C’79, who now goes by Julie Beren Platt [see sidebar]. Perhaps not surprisingly, she remembers the production as a “terrific, fun experience.”

The eccentric structure of the Quad offered other opportunities for the resourceful showman. When the Quadramics staged A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, which requires three doorways, Platt incorporated the three archways that lead from the Upper Quad into the Triangle.

Then there was the nightclub.

“There was a basement in a building that leads into the lower-level Quad that a group of us turned into a nightclub of sorts,” he recalls. “We got some money from the University, refurbished it, put in lights, and had weekly coffeehouses and cabarets and performances. So the production of that entire coffee-shop venue, and producing the performances every week, was, without really realizing it at the time, a terrific education, involving creative decision-making, logistical challenges, people problem-solving—all elements of what I do as a producer.”

Among those in the club’s opening-night lineup was Paul Provenza C’79, now a film producer and comedian [“Is Nothing Profane?” Nov/Dec], who says that the experience he gained in that venue helped him break into professional stand-up comedy. That it happened at all, he adds, “was in no small part thanks to Marc’s vision.”

Unlike some students, Platt didn’t drift about in search of a calling—even though his calling was not directly related to his academic studies. He was a Phi Beta Kappa sociology major and, in retrospect, something of a poster boy for a liberal-arts education.

“What was great about Penn was that I was able to follow my academic pursuits, which were not in the entertainment arena,” he says. “And yet I could still exploit my creative desires to the maximum. I’ve always felt that that better prepared me not just for law school but for being a storyteller, because I was exposed to so much. What I loved in particular was the vibrancy of the student performing-arts culture, and that there were so many opportunities to produce and direct and act, because so many of the programs were student-run.”

The summer after his freshman year, Platt auditioned—successfully—for a way-off-Broadway musical called Frances. Though it’s a stretch to say it changed his life, it certainly helped focus his ambition.

“That production was very well received in Philadelphia, so the director was talking to me about what to do about it,” he recalls. “My entrepreneurial side came out and I thought, ‘Well, maybe there’s a way to take this to New York.’ And so the marriage of entrepreneurial endeavors and creative endeavors sort of cemented [in me] at that time.”

Paul Provenza remembers that side of Platt emerging: “Marc and I used to watch each other perform quite a bit, and we talked a lot about our dreams and desires to get into show business—and how we were both setting the stage to do just that by getting involved in as many projects as possible at Penn.” While Platt was a “very gifted singer and performer himself,” Provenza adds, “he was very clear that the business of show interested him more—he knew even then that he would rather produce and create projects and help bring other people’s visions to reality than perform himself.”

By his senior year Platt was traveling to New York three times a week, and he managed to raise enough money to put on “an off-Broadway equity showcase” of Frances.

“It was during that experience that I realized being a producer was a very exciting thing,” he explains. “It satisfied my creative needs; it let me be in control; and it allowed me to satisfy the business side that interested me. Dealing with lots of people, and having a very large vision of something—I found that more satisfying than being an actor.”

Frances was “very successful” in its relatively small venue, says Platt, and its success prompted him to try to move it to a larger venue “where it could really have a commercial run.”

Enter Reality, stage right.

“I was confronted with agents, and managers, and lawyers,” he says. “I knew what to do creatively; I knew what worked on stage and what didn’t. But I didn’t really understand the business vernacular; I didn’t know the issues; and I lost the opportunity to move that show to a larger venue.”

He pauses, just for a moment.

“I vowed then and there that I was always going to be the smartest guy in the room,” he says. “Because I wasn’t going to work so hard in a creative pursuit and then not know how to facilitate it to becoming a commercial success.”

A few steps were necessary before Platt, already a very smart guy, could walk into a room and know that he was the smartest guy at the table.

His first stop was NYU Law School, where he made the Law Review his first year. By the following summer he had landed an internship position with Elizabeth McCann and Nelle Nugent, then among the premier producers on Broadway. The experience he gained while interning for them the next two years “taught me the Broadway business,” he says simply.

His goal on graduating from law school was to start working as a Broadway producer as soon as possible. But when McCann suggested that he practice entertainment law for a while to get some practical experience, Platt took her advice. After about a year in the trenches of entertainment law, his lucky phone rang. On the other end was Sam Cohn of International Creative Management (ICM), one of the top agents in the business, with a large and glittery stable of clients.

“I need to hire a lawyer who can sit at my desk and negotiate on behalf of my clients, because I have so many of them,” Cohn told him. “It’s a full-time job just being on the phone with me and then taking the deals I make and translating them into contracts.”

Platt was intrigued by the opportunity, and so, at the ripe old age of 25, he found himself at the table with Mike Nichols and Woody Allen and Meryl Streep and Robin Williams and Whoopi Goldberg and Arthur Penn and Peter Yates and Robert Benton …

“It was a wonderful time, a very exciting time for me,” he says convincingly. “I got to know Bob Fosse very well, which was a thrill for me. Jessica Tandy and Hume Cronyn, two great stage actors, adopted me as sort of their grandchild. I learned an awful lot, not just about the business of Broadway but the business of film—which, it very clearly and very quickly became apparent to me, was a much bigger business in some ways than the Broadway business.”

At that point the Siren song of Hollywood began to reach his ears.

“I started to get offers to come out to Los Angeles, first as a lawyer and then as a production executive,” he says. “That is essentially a creative producer working on behalf of the studio—hiring a producer and director, deciding which films get made, supervising the development production and post-production of films on behalf of the studio, which served as both the bank and the distributor. That was something that I took to with much ease, quite frankly.”

By then he and Julie had their first child, Samantha C’05. “We decided, ‘Let’s try L.A. for a year or two, and then we’ll come back to New York,’” he recalls. “That was 18 years ago.”

He started as vice president of production with RKO Pictures, then took the same title at Orion Pictures, whose management he knew from having represented Woody Allen for ICM. “It was a fantastic company,” he says. “Woody made all of his movies there.”

Two particularly memorable projects came across his desk there. One was a film about a disillusioned Civil War veteran who heads West and forges a new life among the Sioux. Actor Kevin Costner, who had never directed a film before, brought in the screenplay, half of whose dialogue was in Sioux.

“Kevin brought it into Orion Pictures and said, ‘Not only is this film three hours long, and not only is half the film not in English—it’s subtitled—but I’m going to direct it and star in it,’” recalls Platt. “And thank goodness all of us at Orion bought into it, and he made quite a great film and won eight Oscars, and the rest is history.”

For Platt, it was, once again, a matter of following his passion.

“When I have thought with my heart over my mind—and not just with Dances With Wolves—I’ve often done great work and had great success,” he says. “That’s the scariest place to be because—especially when you’re on the business side of things—you tend to inform everything with your mind. What looks good on paper, what makes economic sense, what is the right résumé for a project, is not necessarily a recipe for success.”

The Silence of the Lambs was originally brought to Orion by Gene Hackman—who “ended up falling out of the project,” says Platt, at which point “we gave it to Jonathan Demme.” The result was a multiple-Oscar-winning thriller whose main serial-killer character, the cannibal Hannibal Lecter, became a household icon of terror and transformed Anthony Hopkins into a superstar. It was also widely viewed as an artistic triumph.

With two huge hits already on his resume, Platt, at the age of 31, was promoted to president of production at Orion. (In Hollywood, the terms president and president of production are often used interchangeably.) He was, by his own account, “at the pinnacle of film-making in Los Angeles.” And he was just getting started.

“You fellows don’t write, you don’t act, you don’t direct, you don’t sell the pictures. I can’t figure out your job. Oh, yes, now I get it: You fellows are the producers!”

—Groucho Marx at a 1950 awards ceremony.

The producer may not have the least understood role in show business. (I nominate best boy.) But it’s definitely up there. Especially for someone like Platt, who has moved seamlessly from off-Broadway plays to films and TV to Broadway, and enjoyed dizzying success in all of them. What, I wonder, are the ingredients of a successful producer?

“There are many elements,” he answers. “It’s the ability to facilitate—to facilitate individuals, to facilitate talent, to recognize good stories and special talent, to navigate a business with something that’s intangible, whether it’s a play or a film. To navigate the film business, the studio system, the marketing distribution, the pressures that come to bear when you work with a studio.”

In his case, the formula seems to be equal parts talent, drive, and people-skills.

“There are two ways to survive in Hollywood,” says Stacey Snider C’82, who worked with Platt as president of production at Tri-Star and later at Universal; she is now co-chairman and CEO of DreamWorks. “One is, if you have the best project, you win, because people are always drawn to great projects. Marc’s got really unique skills, in that he has great taste and is always attracted to interesting, provocative, ambitious pieces, and he is very hands-on when it comes to production. He is there when you need him—and that’s what you want from a producer: someone who manages the larger vision but also keeps an eye on the details.

“On a personal level, Marc is tenacious and hard working, and he is also a very fair and loving and soothing person, so people want to go out of their way to make sure he does flourish,” she adds. “If it’s a close call, people tend to give a break in Marc’s favor because they like him.”

But at the heart of Platt’s success is his skill in telling a good story and his savvy in getting it to people. “It’s having a vision and knowing how to bring that vision to fruition,” he says. “Getting people to do what you need to do—and picking the right people. Especially the right filmmaker, director. Then, knowing when to say, ‘Go with the director,’ or when to overrule the director. When to continue cutting the film or taking out scenes or when it’s right. What the right music is, when to release the picture.

“What’s interesting is nobody really has the monopoly on the right answer,” he points out. “I always say my friend and mentor Steven Spielberg sort of does, but most people don’t, because there’s really no such thing as a bad idea in my mind. It may not work, ultimately, but ideas are just that—they’re ideas, and they can come from anyone and anywhere.”

Asked what was the most challenging film he’s produced, Platt doesn’t hesitate. “Philadelphia,” he says. “Nobody wanted to go near it. To make a movie about a gay attorney who’s wrongfully fired because he had AIDS—this is in 1990, a very different time in our country—it’s hard. In 1992, even at my own company—I was president of Tri-Star at the time, and I worked for Sony—and even Sony had very, very significant barriers and challenges that many times almost prevented that movie from getting made. It took commitment and passion, not only from myself but from the filmmaker [Jonathan Demme] and the writer [Ron Nyswaner], and the actors [Tom Hanks and Denzel Washington], both of whom worked for far less than their usual fees in order to make the film work.”

“Marc believes Philadelphia is the most important movie he’s ever made,” says Julie. “He’s extremely proud of it. It brought the face of AIDS to the American movie-going audience.” The Platts, along with Demme and some of the other notables behind the movie, were invited to the White House by President Bill Clinton for a private screening, she adds. “It was such a significant film that he wanted to watch it himself.”

Oddly enough, one of Platt’s personal favorites—“a little tiny movie” called Rudy, about an undersized kid whose goal in life is to play football for Notre Dame—was also one of his biggest box-office disappointments.

“I loved that movie,” he says. “Loved everything about it. I was president of Tri-Star at the time, and when I was testing the movie, the market-testing consistently scored as the highest movie I’d ever tested. Higher than Sleepless in Seattle, higher than Silence of the Lambs, higher than Jerry Maguire. And yet when it opened at the box office, it was not successful at all. It was a big disappointment.

“What I have since discovered is that somehow, through the life of DVD and cable television, this film is actually a widely known and beloved film. That’s a great joy to me.”

Having gone from president of Orion to president of Tri-Star in 1992, and to the same slot at Universal four years later, Platt had compiled a dazzling filmography. By his third year at Universal, though, he was getting restless.

“When you’re an executive, the more successful you become, the further removed you get from the creative process,” Platt points out. “You can own something to a certain extent, but it’s very different from being in the trenches and being on a set every single day or being in rehearsal of a play from morning till night. I’d been an executive for many years and quite frankly I tired of it. It wasn’t satisfying me.

“I was ready at this point in my life to own what I was successful or not at and have found that to be just enormously satisfying,” he says. “Both in success and failure. You know, the failures hurt deeply but they’re mine. And I like that.”

Marc Platt Productions is located on the grounds of Universal Studios, which gets first dibs on all of his projects. If they turn one down, he’s free to peddle it elsewhere. He did that with Legally Blonde, which first came across his desk at Universal, and which ended up being financed and distributed by MGM.

“Legally Blonde is a film that I always believed in, and there was only one person that I wanted to play that role—period,” he says. “It was Reese Witherspoon, and she was, at the time, not a star. She’s a very, very smart woman, very eclectic taste. And she wasn’t interested in Legally Blonde. And I pursued her and pursued her and convinced her that not only was she the only one to play this role, but by her playing the role she could create something quite memorable.”

“Platt is renowned as a producer of films for teenage girls,” wrote Dade Hayes and Jonathan Bing in their 2004 book, Open Wide: How Hollywood Box Office Became a National Obsession, which chronicles the high-stakes production and release of several 2003 summer big-budget films, one of which was Legally Blonde 2: Red, White and Blonde. Noting that two of Platt’s five children are daughters, the authors added: “he excels at devising what he calls ‘character environments’: settings where audiences want to spend ninety minutes and people with whom they would want to be friends. Though no one in the film business would want to admit it, it’s the same operating principle that governs TV sitcoms. Though Legally Blonde remains his high-water mark, his résumé includes rocker-girl romp Josie and the Pussycats and Flashdance-y hip-hop melodrama Honey. Even Wicked … turns on the catty rivalry between Glinda the Good and the Wicked Witch echoing scheming snob Selma Blair’s rift with Reese Witherspoon in Legally Blonde.”

Though the book on the whole portrays Platt quite sympathetically, that description does pigeonhole him and, in the process, short-changes him a bit. It may also explain why at one point in our interview he emphasizes the need to explore new styles and contents.

“For a little while, every movie about a young girl or female empowerment came my way because of Legally Blonde,” he says. “And that’s all well and good. It’s a market I understand really well. But it’s not my only interest. As a producer, you’re lucky to get to pursue lots of different ideas and genres and tones.”

It wasn’t a surprise that Marc Platt Productions would hit pay-dirt on the big screen. But Platt himself still had some unfinished business.

“My whole tenure in Hollywood, while successful—and I was lucky to be involved with many well-known films—I did sort of look over my shoulder a lot of times and think: ‘What’s going on on Broadway? Am I ever going to get back to what I initially thought I wanted to do?’”

Platt first read Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West while he was at Universal. Having sensed right away that there was something huge lurking in Gregory Maguire’s strange blend of folk-tale fantasy, political parable, and pop-culture witch-bonding, he wanted to be the one to bring it to life.

“My heart told me, ‘This is a story that’s going to work on many levels,’” he says. “I thought it was going to be a film first. I requested and was given that project to be the producer and develop some screenplays. But they just weren’t satisfying to me. Something was missing.”

Not long after he moved to Marc Platt Productions, he got a call from Stephen Schwartz, the composer and lyricist. “He said, ‘I know you’ve got the rights to Wicked. Did you ever consider making a musical?’” Platt recalls. “And the moment he said it, the light bulb went off in my head, and I realized that what’s missing is the music. It’s a world that wants to be musicalized. It’s a fantasy.”

Bringing it to the stage proved to be “a really intensely creative and enormously rewarding experience,” he says. In addition to Schwartz, Platt brought in Winnie Holzman, a playwright who had created ABC’s My So-Called Life. (“I knew she’d understand the two girls and their angst,” he says.) The three of them spent months in Platt’s L.A. office “beating out the story,” sometimes following the novel faithfully; sometimes not.

“Marc is really the one who created the show, along with the authors,” says David Stone C’88 [“Dramatic Entrance,” June 1998], the other lead producer of Wicked. “I actually think that what is on stage is as much, if not more, Marc’s vision than Winnie or Stephen’s or [director] Joe Mantello’s. He’s so involved in shaping a show. We’re all involved creatively, but I’ve never seen anyone who’s so good with a script and material as Marc is.”

“We discovered that we had this great opportunity of really delving into the rest of the characters of The Wizard of Oz and telling the origins of these characters,” Platt explains. “Also, the relationship between the wicked witch and the good witch really took shape, and as long as those two characters were together we realized it was very exciting.”

The story of the two girls—the green-skinned, outcast, Animal-rescuing Elphaba and the blond-haired, hyper-popular Glinda—required a “lot of inner dialogue,” he adds. “In a film, it’s very hard to get at inner dialogue. You either have to have a voiceover or you have to create the best-friend character you can tell your thoughts to. In a musical, you can literally sing what you’re feeling.

“It seemed like the perfect idea,” he concludes. “And, as it turns out, it was.”

It wasn’t all smooth sailing. “It was pretty close to a five-year process before it got on stage,” says Julie Platt. “It was not quick and it was not easy. Many times Marc said, ‘This is a train wreck and it’s never going to happen. I don’t know what I was thinking.’ But somewhere in his heart I think he always knew that this was the one.”

Platt doesn’t linger on the difficulties, but he doesn’t deny them, either: “When you have a strong director, as we did in Joe Mantello; strong authors, as we did in Stephen and Winnie; strong producers and designers—harnessing all of that energy and intensity was a challenge.”

Yet audiences responded passionately “from the very first reading we did, just actors sitting on chairs in Los Angeles,” he recalls. “And that was our experience every time we put it in front of an audience, in any version. Even when we put it in front of a paying audience in San Francisco and there were songs that didn’t work and the casting was wrong, the audience response was always through the roof.”

After that opening run in San Francisco, partly at the insistence of Stephen Schwartz, Platt shut down Wicked for three months, an unusually long time to retool.

“I decided there was so much at stake and the show was so complicated that before we ever went out of town, we should do something different,” he explains. “I said, ‘Let’s spend more money; let’s make our budget bigger; but no matter what happens in San Francisco, let’s shut the show down—move ourselves not in six weeks but a good three, three-and-a-half months. We’ll put the design in storage, and we’ll do the kind of contracts with actors that’ll allow us to get them back.’ That’s more expensive, but if there was work to be done, I didn’t want to feel like I was on a train that was traveling a hundred miles an hour, with no time to effect changes.”

It was a high-stakes gamble. Even before he made that decision, the budget was already a whopping $12 million.

“I convinced everyone that the way to protect the $12 million was actually to spend $14 million,” Platt says. “That was the additional San Francisco cost. Turns out, we used every minute of that three months. We did retool the script; we did change some of the music and orchestration; we did recast two of the lead characters; we did make scenic adjustments and enhancements. And I think the show benefited tremendously from it.”

The rest is Broadway history.

“Wicked is a very, very rare occurrence—an original Broadway musical smash hit,” points out Stacey Snider. “If you put all those words together, it’s something that happens once in a blue moon. You’re more likely to get hit by a meteor.”

“It is my lifetime dream,” admits Platt. “Ever since I was a kid, I wanted to be a Broadway producer. I didn’t realize it would be with Wicked.”

SIDEBAR

Love Story

Warning: This story contains high-fructose corn syrup. (Well, it could.)

It began their first week as freshmen in the fall of 1975. He had just moved into the Quad. She was still settling into Hill House. One night she ventured across Spruce Street, because she had heard that the action was in the Quad.

“I walked into a dorm room and met my husband,” says Julie Beren Platt simply. And the rest is history.

Though they didn’t actually start dating until the following spring, it’s fair to say that they hit it off pretty fast.

“I think that every woman has some kind of checklist in her head, hopefully one with shared interests and shared passions,” she says. “And it became evident to me very quickly that with Marc, I could check off every item on the list.”

That checklist included the word theater, of course. Asked if she acted, Julie responds: “I sing.” Whatever—she performed in a couple of the Quadramics’ plays, including the production of Peter Pan that Marc directed in the Quad [see main story]. “We were best friends,” says Julie. “And then we fell in love.”

They also sang a lot together, including in the Hebrew-music singing quartet that they formed, and they still love to sing—sometimes with their five children. (Their older son Jonah, now a sophomore in the College, sings with Off the Beat.) And in the spring of their senior year, they became engaged at Penn’s Hillel.

Considering Marc’s high-velocity professional life and hers—she’s a full-time volunteer fundraiser in southern California with a long list of leadership positions, not to mention a Penn trustee—one could be excused for wondering how they’ve managed to find time to raise five children.

“Both of us frankly, more than anything, just wanted to be parents,” says Julie (who had already advised her interviewer that if the phone was busy, it would be because she was talking to one child or another). “So it may sound like it’s something difficult, but it actually is the most pleasurable part of our lives.”

“They’re awe-inspiring as a family,” says Stacey Snider. “All their kids are talented, sweet, good kids—and with five kids that’s pretty remarkable. And Julie is really a great wife-friend-partner to Marc.”

“It is rare in the business in general to have someone who not only has talent but also has integrity and is a good person,” says producer David Stone. “Marc’s family is where his strength comes from. It’s a rough business, the entertainment business. He’s grounded because of that.”

Given their deep involvement with Penn and their long history with the performing arts, the couple recently made a major gift to create a home for student performing arts. The Platt Student Performing Arts House, which is scheduled to open in September, will feature some 13,000 square feet of much-needed office, rehearsal, and performance space in the lower level of Stouffer College House.

“Penn’s theater and music programs had a profound impact on our lives, not only in what we learned but also in the fun we had and the friendships we made,” explains Marc. “The programs gave us the invaluable experience of being part of a team—one where people share creative ideas and pool their talents to bring forth a full production that reflects the best of everyone’s gifts.

“There was a joke in Hollywood that to work for me, you had to have gone to Penn,” he adds. “So many of the people that I’ve worked with or hired—Stacey Snider [now head of DreamWorks]; Alli Brecker [C’85], co-president of production at Paramount; Kevin Misher [W’87, head of Kevin Misher Films, former president of Universal]—they all went to Penn. And the performing arts there played a big part in my life. I have always felt that the education I got both in the classroom and out of the classroom really contributed to the success I have today.

“So when this opportunity came up, Julie and I looked at each other and said, ‘We’ve enjoyed being benefactors to the University in other areas, but in terms of a very large gift, we couldn’t think of anything better than a student performing-arts center.’”

In the eyes of former Glee Club director Bruce Montgomery, who once wrote a part in a club musical (The Magus) to showcase Platt’s boyish, wide-eyed appeal, what’s most remarkable about his former student is how little success has changed him. “He’s the same now as he was then,” says Montgomery. “He’s just remained a loyal, wide-eyed, wondering friend. It’s astonishing. ’Cause he’s been everywhere and done everything—and everything he’s done has been successful.”

—S.H.