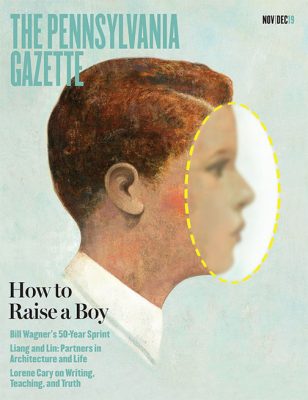

What boys need, Wags is a wow, fighting lullaby, and more.

Great Article!

Congratulations and appreciation to the Pennsylvania Gazette! After finishing (absorbing!) the article “Toward a New Boyhood” on Michael Reichert’s book How to Raise a Boy [Nov|Dec 2019], I sat for over an hour letting memories and emotions escape (for lack of a better description) over remembrances of the course of my male upbringing in the classic Darwinian tradition. I could use the words epiphany, enlightenment, or just hard-core experiences brought back to life, but regardless it was just remarkable going back to the grammar school era and the ensuing voyage that we all had to travel (endure!) to reach our manhood and success, whatever that was or is!

Probably one of the best articles that has been written in the Gazette since I began receiving it upon graduation from University of Pennsylvania. Having given much thought over the years to the circumstances described by Michael Reichert in his book, I have come to many of his conclusions in trying not only to understand (justify) my upbringing but also our society in general today.

I was fortunate to be raised in a small town with second- and third-generation families never leaving. In my personal case, my grandfather and father were both loving and mentoring at all times. Both were the classic war veterans (World Wars I and II) and Great Depression survivors—as most if not all of my childhood peers’ families were also.

Our upbringing throughout most of those times could be described as, or compared to, “Boot Camp” when it came to dealing with our emotions, relating to our fellow classmates, and athletics. In the 1950s and ’60s it truly was the best of times growing up and going to school. However, the concept of Reichert’s peer discussions at Haverford, which I think is fantastic, probably wouldn’t have been as effective as they are today!

With all the societal problems that we see today (too many to list) Reichert’s concepts are definitely headed in the right direction to improve many of the current dilemmas we are facing not only in child behavior but adulthood also! Great article!

Mark Judy D’71, Laguna Beach, CA

Missing: Role of Fathers, Impact of Divorce

Michael Reichert’s blueprint for raising the next generation would have more credibility if he (and journalist Trey Popp) showed a little more appreciation of boys’ needs for a positive paternal role model. The word father appears in the article only a few times, and then mainly in reference to negative qualities of Reichert’s own father.

All the emotional group therapy and catharsis in the world is a poor substitute for the often absent father in the contemporary household. Divorce, and “never married,” have become terrible norms in our society. But while the word father at least makes a brief appearance in the article, the word divorce doesn’t show up even once. If Reichert’s book gives the matter its due, then Popp has done Reichert a disservice. If the apparent unimportance of stable two-parent homes represents Reichert’s own work, then I’m inclined to discount much of the rest of his new age therapy.

Steve Stein W’61 L’64, Larkspur, CA

Skip the “DNA Damning” of Boys

It was interesting to see the cover of the Pennsylvania Gazette, revealing an article inside entitled “Toward a New Boyhood”—an article following one I happened upon in the October 2019 issue of Commentary magazine by Mary Eberstadt, “The Lure of Androgyny.” Clearly, the #MeToo movement has spawned a new cottage industry, dedicated to examining, recasting, and expounding upon the urgent molding of the role of the future or present male child, in an age where, as proclaimed by the grande dame, Hillary Clinton, “the future is female.” Although Reichert’s book, How to Raise a Boy, compared to Eberstadt’s Commentary article, can fairly be deemed “Androgyny Lite,” what is behind the immediate and sudden need for us to focus upon reconstituting and refiguring today’s boys in a manner reminiscent of a quasi-feminized and gentle sociological and psychological manufactured Frankenstein? Of course there are, and have been, delinquent male youths, as there have been naughty girls, but the overarching truth is that there is nothing inherently, chemical or otherwise, demonstrable in the male child today, or in the past, that needs a psychological DNA damning.

Joel Lewittes C’56, Aventura, FL

A Mother—and Feminist—on Raising Boys

I commend Michael Reichert’s work with young men on developing emotional sensitivity. I was sensitive to the mentioning of the meeting at Haverford School—where my son and his fellow soccer teammates from Archbishop Carroll had to put up with Haverford soccer player brats calling them “poor boys” throughout the game! Coincidentally, I too have visited Kamloops, BC—mentioned in the article—but no similar experience with the Sorrento Centre.

The “learning style” Reichert and others lament is so simple. Visual, auditory, and kinetic modes of learning? I am a visual learner. I am a former elementary school teacher and a mother of one boy, now a 34-year-old man and a first-time father. His father and I divorced when he was four, but we co-parented very well. How my son parents his eight-month-old son is something beautiful to behold. I am a feminist and I know that that played a role in my son’s emotional education.

The title “How to Raise a Boy” strikes me as Stepford-like. Something like “Raising a Boy” might have been better. Something missing from the article is even a small mention of raising a boy from birth. As many people now know, the years from birth to three are critical. How boys are spoken to, handled, what TV programming is allowed, encouragement of friendships with boys and girls, are all critical factors. Beyond the earliest phase, I like how the writer Calvin Trillin put it: (paraphrasing) If you don’t make your children your life, you may as well forget it.

For boys to fully develop their masculine and feminine sides, they need adults in positions of authority who show some vulnerability, who they can actually like and admire. I am in absolute agreement that boys/young men “have a right to be happy … and a right to feel good.”

Vicki Rothbardt Oswald GEd’89, Wyncote, PA

Comment

I found only one sentence in need of comment in this article: “Michael wasn’t a big kid, but that didn’t stop him from throwing the shot put on his middle school track team …”

No one throws the shot put; the Shot Put is the name of an athletic event. There is no such thing as a “shot put”; one puts the shot. The shot was the ball that was put into a cannon and shot out to hopefully kill the enemy.

I realize that it is expensive to have actual editors who read the stories first, but … wait. The author is an editor. Let me edit my last sentence: I realize that it is expensive to have a competent editor read the stories first.

The rest of the article is what it is.

Sheldon Waxman W’72, Livingston, NJ

Missing Ingredient

As board chair of a nonprofit helping hundreds of recovering heroin addicts in the difficult struggle to overcome their addiction, we have found that peer counseling sessions for these men, who average 33 years of age, are very helpful largely due to needed encouragement. But I don’t know how Michael Reichert can discuss boys growing into fully functional young men of distinction without even mentioning the importance of the Word of God in their lives. Extensive studies have shown that spirituality (yielding to a higher power) is the most important ingredient in the transition.

J. Philip Robertson WG’60, Dayton, OH

Kudos for Trying

Trey Popp wrote a meaningful piece. Top drawer stuff! I also loved reading about Michael Reichert and what he has been through. Quite a guy.

I am 75 now. I was molded by WWII heroes: my dad, uncles, friends’ dads … No one will ever convince me that these men had not earned the right to raise their kids in the image of what they had learned was crucial for survival on this tough planet. There is nothing anyone can ever say to persuade me that it is wrong to stand up straight, shoulders back, to look people in the eye, to keep your wimpy mouth shut when you’re at the dentist or getting a flu shot, and, most important, to live by a code of honor to always do the right thing regardless of your selfish, creature comfort desires.

On the other hand, when I think of the asshole coaches (my idols, they were—I hung on their every word) who belittled me, a fat little boy trying so damn hard, but endowed with no athletic talent—I want to puke. I would have done anything to sit down with my peers and tell them how badly that hurt, but there was no exhaust valve in those days. It so corrupted me, I forced myself to get into shape physically, but never emotionally, to play football at Penn State in the early ’60s. I thought that was the only way to become a man. Then I became an Army Ranger, Purple Heart, blah, blah, blah, and my life was forever locked into the male model.

Finally, though, in med school at Penn in my mid-30s, I realized I wasn’t so tough in the face of real tragedy—wards of tormented patients, and more importantly, helpless, anguished families. I handled it poorly by getting angry at the doctors who didn’t give a rat’s ass about the people who looked to them for solace and hope. I talked back, hissed, and pressured, driven to throw their insensitivity back in their faces. It was the natural extension of the macho model I had forced myself to live by as a kid.

On the flip side, when I sat by the bedside and held hands with a cachectic, elderly woman with but hours to go, the nurses whispered I was a weakling; some even reported me to the course director—laughing that I had done a poor job hiding moist eyes. And they were even tougher on the female students, who quickly learned to go along to get along.

Now my precious wife is dying of cancer and, even after 40 years as a physician, I still detest that medical mind set, in both male and female doctors, for their bullying, aloof, privileged demeanor, and their lack of attention to my wife’s needs. They consider only what the algorithm—malpractice insulation—specifies, never providing a shred of hope, a warm hand on the shoulder, a promise to never allow my wife to suffer along the way. The medical pedagogical model is the distillation of Reichert’s argument against the traditional male paradigm of child rearing, but that poison is woven so umbilically into every society, I despair there will ever be a change.

I have blathered on for decades in the medical journals about this. But I am pounding sand. As we all know, it takes eons to change human thinking. At least Michael Reichert is trying. Kudos to him.

Bill Gould M’81, Gold Bar, WA

A Role Model for All College Sports Coaches

I would like to thank the Gazette for the article “The Unlikely Legend” [Nov|Dec 2019]. I played for Coach Wagner for three years in the 1970s and can tell you that he was then, and has continued to be, a role model for all college sports coaches. As players we learned many life lessons from Wags, including how to be dedicated in a team effort to a common cause. But more importantly he taught us that we were at Penn primarily to get an education and what we did as part of the lightweight (sprint) football team was an added bonus and should not take precedence. To this day my experiences as a member of his teams remain the highlight of my days at Penn.

Richard F. Gargiulo C’79, Medford, NJ

Long Live Sprint Football

Wow! What a nice tribute to an about-to-be legend at Penn after this year. Really good stuff about Bill Wagner and his alumni and their love of him; and, of the game.

Long live sprint football and the CSFL, where little guys get a chance to live the game they love that owes its heart and soul today to another Penn great, John Heisman L1892 [“Heisman’s Game,” Sep|Oct 2019].

Very touching, with humor that brings tears to our eyes. Yeah, that one, where we’ll find sympathy in the middle of tears and the other end—in the dictionary!

Peter Clark C’60, Lawrence Township, NJ

Iconic Impact

Kudos to Wags’s iconic 50-year sprint football coaching career and his impact on so many alums. In this age of “one and done,” then jumping to the pros, thanks for the reminder that collegiate sports is really all about camaraderie, competition, and per Steve Galetta C’79 GM’87: “Life Lessons.”

John Paul Lin C’79, Laguna Beach, CA

Justice Done

I just read the Gazette story on Wags and had to reach out …

I must admit that I wasn’t sure how you could capture it all—the longevity, the humor, the unqualified love and appreciation we all have for Wags—but I think Dave Zeitlin did it.

I laughed out loud and teared up several times. Thank you for doing him justice.

Steve Barry W’95, Cherry Hill, NJ

Sleep, Sleep, Sleep, Pennsylvania!

Believe it or not, when I babysat for my infant and toddler grandchildren, I used to sing and walk them around with the Penn fight song [“Gazetteer,” Nov|Dec 2019]. It was the best calming song in my repertoire. The fussy babies turned into a delightful audience and, so far, one of them is a proud Penn grad.

Selma Roseman Davis CW’62 G’62, Bala Cynwyd, PA

Bittersweet Era Captured

One more word on the 1959 Championship football team [“Gazetteer,” Nov|Dec 2019]. I had a front row seat to Penn football during the 1950s as a Munger Man and assistant football coach from 1954 to 1959. It was a bittersweet era with much drama and turmoil at the end of the Munger years. Dave Zeitlin’s article captured the 1959 championship year, the time before and thereafter. More drama and turmoil!

The ’59 team are winners on and off the field! They created a scholarship fund in honor of their coaches (Steve Sebo and assistants) to aid Penn football players. Two or three players receive aid every year.

Contributions can still be made.

Dick Rosenbleeth W’54 L’57, Bala Cynwyd, PA

Gifts with Strings

I will always love Penn and Penn Law but feel compelled to point out that in non-academic circles, a transaction in which $125 million is exchanged for an eponymous name change to one of the oldest, greatest, and most hallowed institutions of legal education in our nation’s history is not referred to as a “gift”—it’s called a quid pro quo.

Charles G. Kels L’03, San Antonio, TX

See this issue’s “Gazetteer” for the details on, and reactions to, this “transaction.”—Ed.

In Praise of Looking Up

Bravo to Jacob Gursky for saying so eloquently, in his essay “The River’s Edge” [“Notes from the Undergrad,” Sep|Oct 2019], what many of us feel in today’s smartphone-obsessed culture! When I drive to work in the morning, I pass a bus stop where nine kids stand, motionless, with their heads buried in their respective phones. No one is interacting with—or even acknowledging—one another. When I was a kid and waited at the bus stop, I choreographed dances, climbed trees, and crafted bracelets out of grass with my bus stop mates. In my 40s, I’m too young to be waving my proverbial cane and grumbling “kids today,” yet here I am. I’m grateful that I’m not alone in my sentiments.

Dara Lovitz C’00, Philadelphia

Keep Presenting the Past

I don’t know if you’ve been including a historic photo at the end of the magazine for very long, but I noticed it in the Sep|Oct 2019 issue [“Old Penn”]. I wanted to let you know how much I enjoyed it. The history of Houston Hall is interesting and particularly so for me as a restoration architect.

I hope you continue to share these 19th century views of the campus as I am no longer in Philadelphia to access the University archives.

Andrea Mones CW’72, Bethesda, MD

A Terrible, Valuable Experience

Kudos to Malcolm B. Zola on his letter regarding national service [“Letters,” Sep|Oct 2019]. I would add military service as well. As a young man I was inducted into the military at the age of 18 and served two years, with a one-year tour of duty in South Vietnam. The majority of people I served with there were underprivileged and came from the inner cities and rural areas of the deep South. Many, too many, were African American. During that time we were a family: we were exposed to and learned each other’s culture, had each other’s back, and worked together toward a common goal—to see that each member made it back to the “world” alive and in one piece. That mission was not always accomplished, but we never stopped trying. That experience, as bad and as terrible as it was, enabled me to develop the interpersonal skills that to this day allow me to understand and appreciate all of my fellow Americans.

Richard T. Harvey WEv’80, Ft. Myers, FL

McHarg in Full

As one of the two surviving members of Ian McHarg’s first graduate landscape architecture class, I enjoyed JoAnn Greco’s portrayal of McHarg in “A Man and His Environment” [Sep|Oct 2019]. I had never known that Mrs. Barnes had been our benefactor. McHarg would not reveal her name, saying she preferred anonymity.

I responded to an advertisement in the Architect’s Journal, a UK publication, which invited applications to a graduate program in landscape architecture at Penn, offering tuition and a $2,400/year stipend. Those with an architectural degree could complete the program in “one year.” To a young English architect, $2,400 was a lot of money, which is why McHarg dangled the bait overseas, knowing that to an American $2,400 was not much of a stipend! McHarg had another reason for wanting architects to apply: we would be able to prepare professional quality drawings that would help him gain ASLA accreditation for the new program. I was accepted at Penn and invited to apply for a Fulbright Traveling Scholarship, which paid my way to and from the US.

Of the eight original graduate students, six were architects, one had a degree in horticulture, and I had degrees in architecture and city planning. Two were from Scotland, four from England, and one each from Australia and Holland. There were also four American undergraduates in our group; they did the same classwork but received BLA degrees.

Things got off to a rocky start when we discovered that Penn was going to take tuition out of our stipends. Tuition at that time was $600 per semester, so all our stipend money was committed for the duration of the program. Also the program would be an “academic year,” which was four semesters lasting a year and a half. Not to worry, said McHarg: he would find us part-time jobs in Philadelphia. And he did. Most of us worked in architectural offices and were receiving salaries equivalent to McHarg’s Penn salary!

Initially, the new program’s agenda was similar to other landscape programs in the US. Our early projects included an urban subdivision, urban park, rehabilitation of an industrial island on the Schuylkill River, and a plaza design for the Seagram Building taught by Phillip Johnson. In spring semester, however, we started to tackle a design involving natural processes: this was a project sponsored by the National Park Service to articulate a development strategy for the North Carolina Outer Banks. It was McHarg’s first opportunity to teach his theory of design with nature. But there would be many more iterations of his method before Design With Nature was published and became the agenda for the Penn program.

Following graduation the Scots returned to Scotland, the Australian to Australia, and the Dutchman to Holland. One English architect remained in Philadelphia, one returned to London and opened a landscape practice, another took a teaching post in landscape architecture in Edinburgh. With McHarg’s help I began a teaching career at the University of Georgia. In 1973, I became the second dean of the School of Environmental Design and set about adjusting the curriculum to emphasize design using natural process. With McHarg’s advice I hired five Penn graduates (20 percent of my teaching staff). Today, and following the tenures of four subsequent deans, the school has become the College of Environment and Design and is one of the leading programs emphasizing natural process in its design curriculum.

In 1965 I invited McHarg to be our featured speaker at the annual alumni reunion. He agreed to come “for expenses only.” I also invited Eugene Odum, the very distinguished professor of ecology at the University of Georgia, to attend. McHarg knew of Odum, but was surprised to find he was at Georgia and going to be in his audience. This caused him to consume a bit too much alcohol before his lecture. As he gave his lecture, his Scottish brogue became much more pronounced and a wee bit slurred. The audience loved it, even if they could only understand half his words. Odum was enchanted and they both talked for a long time after the lecture.

In 1997 Ian McHarg returned to the University of Georgia at the invitation of the Institute of Ecology, for a lecture promoting his book A Quest for Life. His fee was $10,000. I asked him how he could charge so much. He said his secretary now booked his speaking engagements, and she had found that each time she asked for a bigger fee, no one ever refused!

Next morning I invited McHarg for breakfast. He consumed almost an entire jar of Scottish marmalade! And that was the last time I would ever see Ian McHarg. I miss him. He (and Mrs. Barnes and the University of Pennsylvania) put me on the path to professional success. I am grateful to all of them. Each year I make a donation to Penn in Ian McHarg’s name and to repay the funds that helped me through Penn and established my career.

Robert P. Nicholls GLA’57, Athens, GA

The writer is dean and professor emeritus at the College of Environment and Design (formerly School of Environmental Design) at the University of Georgia.—Ed.