It’s not just about the trophy. As a player and coach, John Heisman was one of football’s fiercest (and trickiest!) competitors and a great innovator, who championed multiple changes that made the sport safer and more exciting.

By Dennis Drabelle | Illustration by David Hollenbach

Warmup

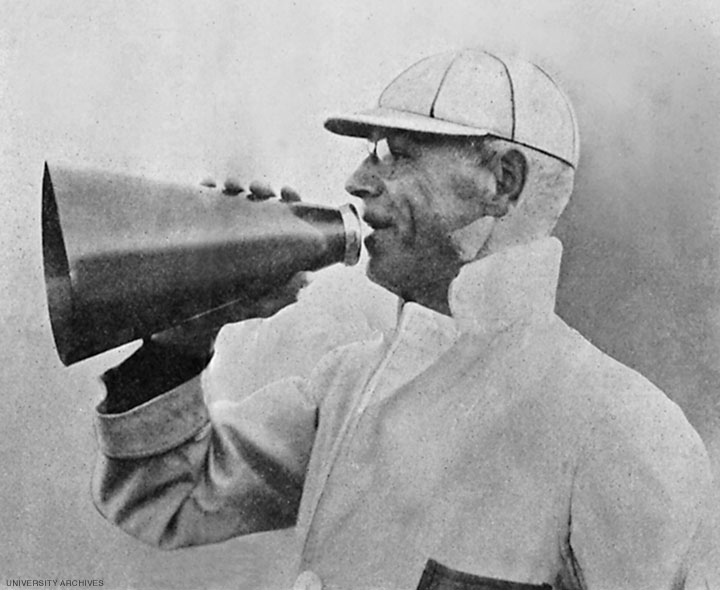

A “free and easy American interpretation of old English Rugby” is how John W. Heisman L1892 characterized the kind of football he played as a kid. By the time the adult Heisman hung up his cleats—and the megaphone through which he coached—for the last time, football and rugby had gone their separate ways. Heisman introduced several innovations to football, including the center snap, the audible “Hike” or “Hut” signal, and a shift that was a precursor to the T and I formations. He also delighted in bending the rules to fluster and deceive opponents. Heisman coached football as he’d played it, with brains (though not much brawn) and love.

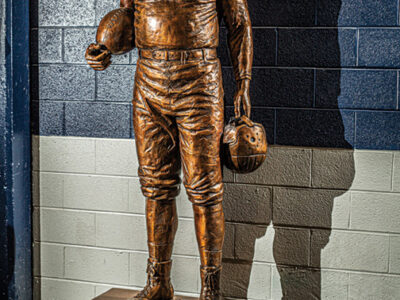

After proposing an annual award for the best college player, he was honored posthumously by having his name attached to it: the Heisman Memorial Trophy, which became one of the most iconic awards in sports. Lately, with football continuing to face scrutiny over concussions and other negative health impacts, some rules have been changed to make the sport safer [“Gazetteer,” Mar|Apr 2019], and more changes are likely to come. Against that background, a fresh look at one of the game’s founding fathers seems especially timely.

First Half

The Heissmanns (as the name was originally spelled) emigrated from Germany in 1858. Michael Heisman was working as a cooper in Cleveland when he and his wife had John, the second of their three children, in 1869. Five years later, the Heismans moved to Titusville, Pennsylvania, where the first successful oil well had been drilled more than a decade earlier. With containers much in demand there, Michael started his own barrel-making business and did well enough with it to send John off to college at Brown. As told in Heisman: The Man Behind the Trophy, a biography by John M. Heisman (a grand-nephew of the first John) and Mark Schlabach, almost every time the incoming freshman found himself between trains on the way to Providence, he sniffed out and joined a pickup football game.

Heisman did well academically at Brown, and despite standing only 5 feet, 8 inches tall and weighing a mere 148 pounds, he played football there as a lineman. (Club football, that is, the only kind the school then had to offer.)

At the time football was very much a work in progress: the center delivered the ball to the quarterback by rolling it to him on the ground, there was no blocking, and teams gained yards by forming a kind of human locomotive. According to the Heisman co-authors, “some runners even had leather handles from old suitcases sewn into their jerseys, so their teammates could haul them along at a more rapid pace.” At first, pads and helmets were considered unmanly; to give their heads at least a semblance of protection from prospective tacklers, players grew their hair long.

Early efforts to coordinate offensive plays were imaginative but risky, as witness an article Heisman wrote for the magazine Collier’s Weekly in 1928. “Messer, one of [Brown’s] gifted halfbacks, was a master of a number of forms of entertainment, among them being the ability to sneeze at will. We were quick to make use of his accomplishments. A sneeze from Messer meant that Fred Hovey, our fullback, was to punt. And all went well until, alas, one day … Messer turned loose an involuntary sneeze.” In the confusion, the punted ball hit a teammate, bounced back, rolled, and came to rest “within one short plunge of our goal.”

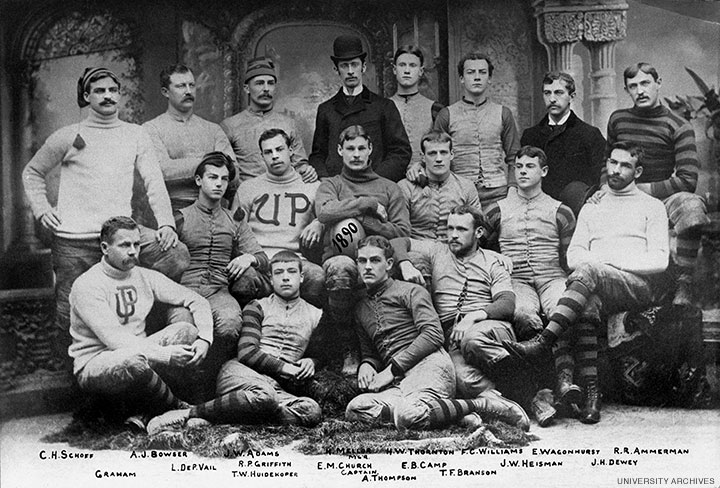

Two years later and 10 pounds heavier, Heisman transferred to Penn to study law, which Brown did not offer. But Penn’s intercollegiate football team undoubtedly figured in the decision, too.

Under a new coach, Ellwood “Woody” Wagenhurst, fin-de-siècle Quaker football was emerging from a period of underachievement. The stage could not have been more invitingly set for a player who brought as much passion and ingenuity to the game as Heisman did on arriving in 1889.

The Quakers went 7-6 in 1889, 11-3 in 1890, and 11-2 in 1891. Bypassing burlier candidates, Wagenhurst often started Heisman at left end. The final game of the 1890 season, against Rutgers, almost ended Heisman’s academic career. The game was played in Madison Square Garden, then an indoor arena at 26th Street and Madison Avenue in Manhattan, which had opened the previous summer. Warming up, Heisman ran under the Garden’s electric lighting system during a pre-game check. The lights came on, emitting fumes that got in his eyes and left him with blurred vision. He played the ensuing game anyway, but afterwards a doctor ordered him to give his eyes a long rest. That meant no reading, not even of textbooks.

Heisman compensated by prevailing on classmates to read the assigned material aloud and then discuss it with him. Impressed by his determination, the Penn Law faculty allowed him to take his final exams orally. On June 6, 1892, still suffering from blurred vision, Heisman was among the 37 recipients of an LL.B degree at the commencement ceremony held in the Academy of Music.

The slow recovery of Heisman’s eyes turned out to be a boon for football. Rather than go to work as a lawyer, with all the reading that would entail, Heisman accepted an offer to coach at Oberlin College, which had just started a football program. And by enrolling as a grad student in Oberlin’s art department, he was able to be a player-coach.

In lieu of sneezy signaling, he came up not only with “Hike” but also with coded directions for the plays themselves. So hairy were these formulas that his players carried around crib sheets to consult between classes. For example, a vowel in a shouted word referred to the right halfback, a consonant to the left halfback, and the formula “P 128 def” told the fullback to run around the left end. As Heisman warned three decades later in his book Principles of Football, players must expect “to learn complicated and puzzling signals, and to remember just what they mean.”

At Oberlin, all the memorizing paid off. That first year under Heisman in 1892, the Yeomen beat every opponent, including Ohio State and Michigan. (In those days, Oberlin had the most students of any college in Ohio.)

An incident from the Michigan game, played in Ann Arbor with snow on the field, exemplifies the Heismanized player’s creative approach to football. Oberlin was leading when a huge Michigan ball carrier went galumphing toward the goal line. He was finally brought down short of a score with his jersey rolled partway up and his belly exposed. A quick-thinking Yeoman grabbed a handful of snow and rubbed it on the guy’s bare skin. With a yelp, he dropped the ball, and Oberlin recovered it. The referee (there seems to have been only one) missed what Heisman called his team’s “cold-hearted trick,” and the Yeomen went on to win the game.

Paid only a token stipend by the financially strained Oberlin athletic department, Heisman moved on to Buchtel College (now the University of Akron). Coaching both baseball and football, he sized up one of his pitchers as prime quarterback material. At a height of 6 feet, 4 inches, though, the fellow had trouble bending down to pick up the ball at the start of a play. Heisman had the center toss the ball back and up to the quarterback—and thus the center snap was born.

A season later, Heisman was back at Oberlin, where he chalked up another winning season. His success was noticed, and in 1895 he accepted an offer to coach football at Alabama Polytechnic Institute, an early incarnation of Auburn University. Well aware of what the rules covered and what they did not, Heisman approved a hidden ball trick concocted by the team’s captain.

As Heisman recalled in an unpublished manuscript, during the second half of a game against Vanderbilt, his players “wheeled from scrimmage formation into a swirling ring. This ‘revolving wedge’ held the quarterback, Reynolds Tichenor, in the middle, with the ball. While they revolved and obscured him, he stuffed the ball up under the front of his jersey. Next he dropped [to] one knee and pretended to nurse a sprained ankle, while the circling mass sloughed away from him—likewise the Vandy tacklers who still strove to tear up our wedge. With the leap of a cat arose now the crouching Tichenor and ‘pussyfooted’ 35 yards to a touchdown.” Clever as the ruse was, however, the Alabamans still lost the game.

In 1900 Heisman was hired away by Clemson, where he coached a bizarre game that the opponents had no one but themselves to blame for losing. The Tigers traveled to Greenville, South Carolina, to play Furman on its home field, which had an unusual feature: a big oak tree growing at roughly the 50-yard line. Three different times, Heisman sent in a play that exploited the tree as a kind of screen, and Clemson won 28–0. “Not long after that game,” Heisman recalled, “the Furman authorities consented to the removal of the Monarch primeval from the football field.”

Heisman justified his tricks as weapons against teams fielding far bigger players than his. A squad that puts a premium on wits, he pointed out, “does not need to be composed of men as large as elephants to play successful ball.” But as football matured, new rules choked off more and more opportunities for elephant-taming. Today a field with a tree growing on it would be laughed out of the league, and a rule specifically forbids hiding the ball under your jersey. Players can make feints, and a well-executed double reverse can fake defenders out of their jocks, but the freewheeling chicanery of early football has been, as Heisman put it, “legislated out.” (In 1932, Harpo Marx revived the ball-under-the-jersey trick for the anarchic game between Huxley College and Darwin in the movie Horse Feathers. But then Harpo could get away with anything.)

A game that Heisman coached in 1916 left a blot on his record. A dozen years earlier, he’d moved to Atlanta to coach baseball and football at Georgia Tech. In the spring of 1916, his baseball Yellow Jackets had taken a drubbing from Cumberland College in Lebanon, Tennessee. Convinced that Cumberland had used non-student ringers, Heisman challenged the college to play football against his boys in Atlanta.

The game was the rout of all routs. The Georgia Tech Yellow Jackets led 63–0 at the end of the first quarter, 126–0 at the half. Cumberland fumbled and lost the ball 10 times. To put Cumberland out of its misery, Heisman agreed to end the game 15 minutes early, but by then the Yellow Jackets were ahead 220–0, making it the most lopsided victory in college football history. When pressed for an explanation, Heisman claimed he was trying to cure sportswriters of their penchant for adding up a team’s scores for the whole season, as if the total had some great significance. Say what you will, though, 220–0 smacks of sadism.

Of more importance to football was a reform adopted shortly after Heisman took over at Georgia Tech. The sport had become lethal, costing at least 45 players their lives between 1900 and 1905. Heisman viewed the carnage as a corollary to football’s reliance on beefy men gaining yardage en masse. His recommended solution was a rule-change to legitimize the forward pass, which was then not allowed.

In late 1905, President Theodore Roosevelt summoned a few prominent coaches to the White House for a meeting on how to make football safer. Though Heisman was not among the consultants, a year later he got his wish: the forward pass was in. The death toll declined, and one of football’s greatest strategists had a new dimension of complexity and finesse in which to experiment.

Halftime

There can’t be many other college football coaches who played Hamlet onstage professionally, as Heisman did. He taught oratory at some of the schools where he coached, and acted in summer stock. He got good notices, notably as a light comedian, and his acting brought him in contact with a fellow thespian named Evelyn McCollum Cox, whom he married in 1903. As John’s career branched out—in addition to coaching, teaching, and acting, he dabbled in advertising and speculated in land—he thought he would have more opportunities in the Northeast. With Evelyn determined to stay in Atlanta, they agreed to divorce in 1919. He later remarried.

Second Half

Among Heisman’s many victories during his long tenure at Georgia Tech, where he coached from 1904 to 1919, two stand out. First was beating his alma mater in 1917. Penn had become a football powerhouse, though recently its power was waning. With football still considered a Yankee specialty, the Yellow Jackets’ 41-0 victory over the Quakers was a coup for the South. That year, Tech went undefeated for the third season in a row, including a climactic 68-7 triumph over Auburn. Since the two teams were regarded as America’s best, the Yellow Jackets had a right to call themselves the 1917 national champions.

On learning that Heisman was leaving Georgia Tech and eager to resettle along the Eastern seaboard, Penn hired him as its football coach ahead of the 1920 season. It didn’t work out. The Penn student body was not running the high football fever that Heisman had got used to in Georgia, and he complained that his players weren’t giving him their all—probably as a result of the long hours they put in on their studies. “How am I to conduct practice when only half the squad is able to be there?” he lamented to the Philadelphia Inquirer after a 1920 loss to Penn State. The complexity of his plays exacerbated the problem. When a frustrated halfback wailed, “C’mon guys, just hand me the pumpkin and let me run,” Heisman said, “No … you must learn to hop like a chickadee.”

That avian simile had to do with all the shifting around that Heisman asked of his backfield before the ball was snapped. The hopping was curtailed starting in 1921, when a new rule required the team with the ball to freeze before the start of each play; as a result, Heisman had to rebuild the offense he’d been perfecting for years. By the end of his second year at Penn, he was preparing for the end. In a letter to an old friend, Heisman wrote, “One hates to give up, and I must not quit so long as they actually want me, for it is still my university and I must be loyal whether everybody else is or not.” He left Penn after three years with a 16–10–2 record—hardly a disgrace, but a falloff from his lofty standards. (At Georgia Tech his record had been a scintillating 102–29–7.)

The co-authors of Heisman believe that their subject’s tenure at Penn delivered a belated payoff. “Two years after Heisman left his alma mater, former Penn player Louis Young guided the Quakers to a 9-1 record and a national championship in 1924,” they write. “Clearly, Young benefited from the foundations Heisman had laid before him.”

In 1922, Heisman had published his Principles of Football. As its wonkish title suggests, the book was written for coaches and players, not ordinary fans. But it makes for lively reading, with a prose style ranging from the terse and zippy—“Don’t fumble [the ball]; you might better have died when you were a little boy”—to the metaphorically elegant. For a halfback end run, the blocking fullback is urged to take out the defensive end “by leaving his feet and hitting [the end] at or about the knees, endeavoring to cut the legs out from under his opponent as a skillfully wielded scythe would fetch down ripe grain.”

Heisman the pedagogue did not forget the fans, however. His writing on football also appeared in newspapers and magazines, and he is credited with originating the football scoreboard showing downs and yardage to help them follow the game’s progress.

After leaving Penn, Heisman coached briefly at Washington & Jefferson College in Washington, Pennsylvania, near Pittsburgh, posting a 6–1–1 record for the 1923 season. He moved on to Rice University in Houston from 1924-1927, where he guided a mediocre talent pool to four years of mediocre records, before retiring from coaching. On November 24, 1927, Heisman gave his players a Knute Rockne-like pep talk before what he’d decided would be his finale. “Never before have I asked you to play for me, but only for your college. But if I have ever done anything for which you incline to think you owe me a little, I will appreciate it if you will square the debt today by putting forth the best effort of your lives.” The Owls responded with a 19-12 victory over Baylor.

Heisman moved to New York City, where he kept writing about football, pursued his business interests, and pushed for the award that bears his name. In late September of 1936, he came down with pneumonia. Nine days later, he was dead at the age of 66.

Overtime

Heisman might have been pleased by something that happened this past January. Clemson—a team coached a century earlier by a man who thought too much of football to let it be monopolized by giants—completed its successful run for the national championship without the services of its star 350 pound defensive tackle, who was on suspension.

Dennis Drabelle G’66 L’69 coached a grade-school football team from 1960 to 1964.

This article is the first confirmation I’ve seen of my theory that my family’s name “Heisman” was originally spelled with two “S’s” in Europe, which requires the “S” sound, which we all use in pronouncing our name. So, when the “Ellis Island” change was made to the American spelling with one “S”, others later who did not know the pronunciation assumed by that spelling that it was the one “S” European “Z” sound, hence the mispronunciation with the “z” sound so common these days when listening to the Trophy talk. My paternal great-grandfather, Aaron Heisman, was first cousin to football coach John Heisman (who had no children, to my knowledge).