I don’t have a smartphone. I’m not on Facebook. But it took a longer journey to truly feel free from prying eyes.

By Jacob Gursky

I’d been sitting on my duffel bag in front of the gas station in Cantwell, Alaska, whose lonely gray post office serves about 200 residents, for a half an hour when a big black pickup truck pulled up. The window rolled down to reveal a rugged man with a bushy moustache and a grey plaid shirt that had seen better days.

“You Jacob?” he asked.

“Yeah.”

The door popped open. Mike Santos looked down at me, taking stock.

“You got any callouses on those hands?” he said.

“No, sir. But I’m ready to get some.”

He took a drag of his Kool cigarette and smiled as he said, slowly, “Touchdown.”

Hard work on honest terms was one thing that had drawn me to central Alaska to work for an Iditarod racer for the summer. But the real reason was that I’d become disenchanted with the virtual world’s encroachment on the real one, so I’d decided to try to escape the digital realm altogether.

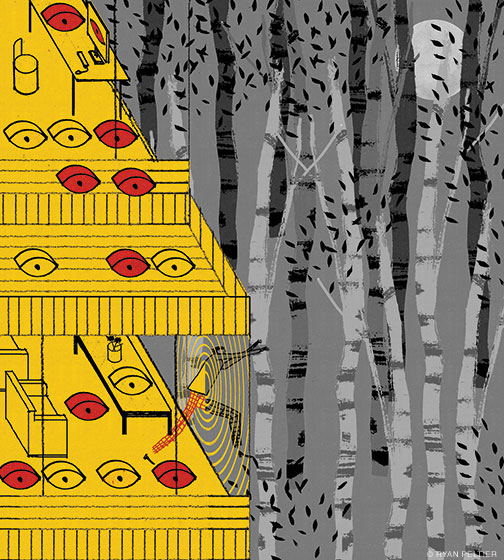

If you asked my friends, most of them would say I’d already done that at Penn. I don’t have a smartphone. I’m not on Facebook, or Twitter, or Instagram. I don’t use a GPS assistant. I like getting lost, and when I do leave home with my old-fashioned TracFone in my pocket, I often remove its battery for long stretches. I’ve been wary of government and corporate surveillance since I was in high school, but a turning point came for me while I audited a “Privacy and Law” course at Penn Law, where I had a chance to meet former National Security Agency Director Michael Hayden, who oversaw the warrantless surveillance program exposed by Edward Snowden. When I asked him about the scope of the government’s ability to pry into people’s lives, he replied, “If you give us the opportunity, we will take it as far as you will let us.”

I do use my student email account, but it rubs me the wrong way. A while back, I went on a date that had been a lot of fun. A week later, an email from my companion landed in my school account, which is hosted by Gmail. Gmail analyzes your messages to build psychographic profiles from which Google can extract value; it is arguably the most invasive surveillance tool ever invented. Before I read the email, I looked at the automated response suggestions at the end:

[Ok] [Sounds good] [That’s great, thanks!]

Then I read the message. My date was informing me that she’d been diagnosed with oral herpes. Now Google knew, and could serve me ads accordingly. That’s great, thanks!

And even if you manage to elude Google or Facebook or Amazon, there’s always a classmate to cheerfully conduct the data collection. Like the time I found myself circled up with 15 friends, drinking and playing “Never-Have-I-Ever.” If you’ve ever played it, you know the rules—the idea is to coax other people to reveal intimate secrets about themselves. But a few minutes in, one of my friends darted out of the room, and returned to place a strange object in the center of the table. While others murmured with delighted excitement, I asked her what it was.

“It’s a 360-degree camera” she said, “so I can remember all of my friends and this moment.”

I don’t think that I’ve ever felt more confused and out of place. My friends ultimately decided that hanging out with me was worth the inconvenience of my objection to all of our secrets being recorded for who knows what end. But it was obvious that I was the lone stickler ruining the thrill for everyone else, and my reaction was somehow considered extreme—as if I was a vegetarian who refused to even be in the presence of meat.

In other circles, sometimes my friends have parties where YouTube is projected on a big screen and everyone does their best to find embarrassing videos of each other, many of which were not posted by their subjects. This is the way we live now. Google catalogues our lives without our consent, sometimes as early as elementary school, indelibly and forever, and makes some of the juiciest bits available to anyone. Many of my peers respond by turning it into something fun. Maybe they’ve accepted this surveillance and exposure as inevitable, and have decided to make the best of it. Maybe they are wiser than I am. Maybe I’m holding onto something that died with the first iPhone, or that never existed at all. I honestly don’t know. I don’t know any other world but this one.

Abstaining from social media means that I am left out of a lot. One of the best things I started doing at Penn was to go out dancing. My social world blossomed. But I remember evenings in the Quad where everyone was dressed up to go out, following their phones like divining rods, and I was left behind feeling miserable that the price of entry was surrendering whatever semblance of privacy I still had, and vaguely cursed to be the only person bothered by it. And even when I made it to the venue, there seemed inevitably to come a point where someone would produce a phone and record the entire dance floor. So I’d end up on Instagram every week anyway, even without an account.

Older generations might have trouble imagining just how thoroughly college life has changed in this regard—or how definitively the old ways have been jettisoned. Penn, for instance, no longer offers landlines in the dormitories. “Only six or seven” people on the entire campus request them each year, I was told, so why bother. As an experiment, I went one semester without a cell phone. I learned that there was only one working pay phone on campus (up the street from the Fresh Grocer, which, incidentally, scans shoppers using automated facial-recognition technology). There was another one in Houston Hall, but it didn’t work. I mentioned this to a student canvassing for student government and she assured me it would be taken care of. A few weeks later, it was ripped from the wall.

In Alaska, I had no internet access and spent most my free time staring at mountains. It was lonely at times, but I wouldn’t exchange the experience for anything. My boss, Mike, had been mushing dogs since he was 18. Obsessed with polar explorers, he and his wife had moved to Cantwell and rebuilt one of the first Denali homesteads by hand. He chopped down trees on his property and built the tourist theater that is his livelihood. Together, with their five-year-old son, they’ve created a rich life for themselves.

When we had time off, we would put down the buckets of dog food and venture into the wild around Denali National Park. Often we’d go fly fishing, but occasionally we’d go just to be in nature. One day in particular stands out in my memory. I was sitting on a flat stone by the edge of a river, staring at rock that jutted out from the current.

I jumped—suddenly Mike was behind me.

“What are you thinking about?”

“I’m trying to imagine how that rock got there.”

“And?”

“I don’t know, maybe it rolled down the side of the hill? Or maybe a glacier put it there?”

Mike laughed at me; it was an embarrassingly scanty theory for the amount of time that I had sat there pondering. But, in that one, stupid moment, I had a revelation:

Wherever I have been in my life, I have almost never believed that I was truly alone. That I was not being watched. I always feel like I am performing—that there’s a camera pointed at me, or will be any second.

But, in that moment, by the river, something happened.

No one, I thought to myself, can take staring at a rock in a river away from you.

There were no 360-degree cameras. No algorithm was looking me up in a facial recognition database. There were no cell towers to triangulate my location. I experience all those things as tiny pieces of myself being removed and swept away to a server somewhere. People always tell me, “I have nothing to hide, so I have nothing to fear” from the constant harvest of their data. For me, it’s different; I feel a loss of autonomy at the point of collection, regardless of how my data is used. Here, there was no one and nothing studying me or analyzing me. Next to this river, I could just exist. It may sound melodramatic—and I think it would be if I was writing this 20 years ago. But I had to go all the way to Alaska to find that experience.

If anyone knows how to deal with feeling like they were born in the wrong century, it’s a dog musher. Later that day I asked Mike how he deals with it.

“Avoid people and drink lots of alcohol,” he said.

I grew quiet. He softened and spoke again, more seriously: “Find something you love and find a way to make a living doing it.”

I stopped to think about this man I’d grown to admire. For all his independence, even he was hardly beyond of the reach of modern life. His business depends on TripAdvisor reviews, and the tourists from whom he makes his living carry phone cameras all over the property. But by embracing it for four months of the year, he’s free to spend the other eight exploring the wilderness with his wife and son and dogs, enjoying some of the most beautiful and untouched land in the world.

I didn’t go to Alaska to stay. I don’t want to drop off the face of the grid and become a dog musher. But I do want to find a better balance between my digital life and my real one, and I hope that if Mike found one, I will find one too.

Jacob Gursky C’19 graduated in May.