Penn’s 1959 football team returns to celebrate a title that still seems improbable 60 years later.

As members of the 1959 football team are being honored before the Penn–Dartmouth football game on October 4, a voice pipes up from the back of the Weiss Atrium, adjacent to Franklin Field.

“Barney’s still our captain!”

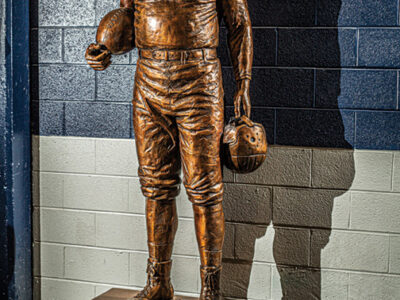

Sitting near the front of the room, Barney Berlinger Jr. ME’60 smiles. Even now, the US Marine Corps veteran and founder of a company that builds transmissions for electric vehicles might be best remembered for a couple of autumn months 60 years ago when he led Penn to its first-ever Ivy League football championship.

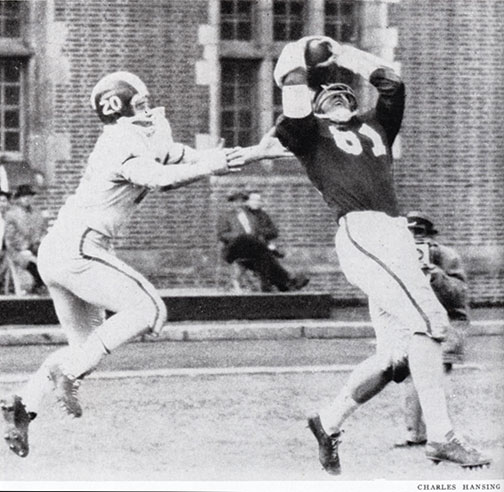

Actually, Berlinger might be best known for one play—a leaping 26-yard touchdown catch on fourth down (see the photo above) that gave the Quakers the lead in their Thanksgiving finale versus Cornell at Franklin Field, propelling them to a title that remains unique because of what came before it (lots of losing) and what came after (Penn’s head coach being fired just as the celebration subsided).

“He made a great catch,” says quarterback George Koval W’61, pointing to where Berlinger is standing and imagining they were back on the field together. “He was [so close] to being out of bounds, and he came down with one leg in.”

“George Koval lobs one to me, and by God’s grace, I catch the damn thing,” recalls Berlinger, who also made sure to credit Jack Hanlon W’60 for making another huge fourth-down grab to spark the comeback.

For Berlinger, it was an easy decision to come to Penn, where his father, Barney Berlinger Sr. W’31, was a track star. But he arrived at a difficult time for the football program, which was struggling in its transition to the Ivy League. After back-to-back 0–9 seasons in 1954 and 1955—coach Steve Sebo’s first two years in charge—the Quakers sputtered through three more losing campaigns in ’56, ’57, and ’58, the first three official seasons of Ivy League play.

Yet Berlinger was hopeful heading into his senior year in 1959, pointing out the skills of Hanlon and leading rusher Fred Doelling C’60 and adding that Sebo was “good at deploying players where they belong.” Koval was optimistic, too. “Coming out of [training camp in] Hershey, we just said, ‘Things are going to work out well,’” the quarterback recalls. “And everything just fell into place.”

The Quakers opened the season with three straight shutouts, including their first win over Princeton since 1952, before crushing Brown. They then met heavily favored Navy—the last remnant of the kind of national-caliber opposition they faced through the early part of the 1950s—and came away with an impressive 22–22 tie on a late field goal from Ed Shaw W’61. “After tying Navy,” Koval says, “we thought, Hey, we really have a shot at this thing.”

Berlinger recalls a “psychological letdown” as the Quakers lost their next game at Harvard. But they finished the season with wins over Yale, Columbia, and Cornell to secure what would be the program’s only championship for the next 23 years. One reason for the title drought, Koval believes, was the administration’s decision to let Sebo go—a decision that actually had been made before the season. According to Dan Rottenberg C’64, in his book Fight On, Pennsylvania: A Century of Red and Blue Football, Sebo was told his contract would not be renewed and that a three-year contract had been given to John Stiegman in September of 1959. But “Sebo’s impending departure and Stiegman’s contract was kept from the public,” Rottenberg writes, “so the University’s embarrassment was that much greater when Sebo produced a championship team in 1959 and the University announced, at the end of that season, that he had been fired. The sportswriters had a field day: Penn was so devoted to Ivy principles … that it renewed a coach’s contract only when he lost and fired its coach only when he won.”

The players marched to College Hall to demand answers from Penn President Gaylord P. Harnwell Hon’53, “trying to reverse the situation,” Berlinger recalls. “Of course, they couldn’t reverse the situation. The die had already been cast.” Adds Koval, “[Harnwell] being a nuclear physicist, I think we all walked away from there saying, What did he just tell us?”

Koval was named captain in 1960 but struggled in Stiegman’s new formation as the Quakers finished the first of five straight losing seasons under the new coach. “I think it may have set Penn back a few years,” Koval says. “When you fire a coach in the Ivy League for winning a championship, families and high school coaches start saying, ‘What are you doing?’”

Despite his senior-year disappointment, Koval remained at Penn for many years, working in the University’s financial aid office and then as the deputy vice president for university life. And he still loves to return to Franklin Field with his old teammates—who were recognized, on the field, during the second quarter of this year’s Penn–Dartmouth game—and think about the 1959 season in which students tore down the wooden goalposts and tossed them into the Schuylkill after every win. (Not all of the wood made it into the river, though—some alumni have told the Gazette they’ve kept pieces, with one donating his collection to the athletic department.)

“I’m amazed no one got killed,” Koval says. “The band would be marching under the goalposts and the students would snap it. People were hanging on them. … But when you’re in a drought for that long, every win becomes special.” —DZ