A half-century after the publication of his pathbreaking manifesto, Design With Nature, Ian McHarg’s work is more urgent, timely—and influential—than ever.

By JoAnn Greco

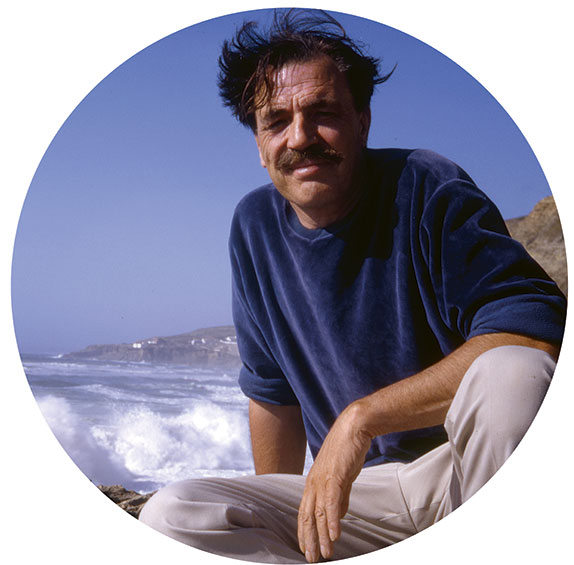

Fifty years ago, Ian L. McHarg was in the thick of planning for what would become the world’s first Earth Day the following spring. As chair of Penn’s Department of Landscape Architecture and Regional Planning, he had committed his faculty and students to participate in what had been conceived as a national teach-in. In his 1996 autobiography, A Quest for Life, McHarg recalled that his specific task was to identify and invite potential speakers for the Philadelphia event. Among those who answered the call were Ralph Nader, then best known for his 1965 exposé of the auto industry, Unsafe at Any Speed; US Senator Edmund Muskie; Nobel prize-winning biochemist George Wald; poet Allen Ginsberg; and the cast of the era’s iconic Broadway musical, Hair, which, in addition to “Age of Aquarius,” featured a song called “Air” that begins:

Welcome! Sulphur dioxide

Hello! Carbon monoxide

The air, the air

Is everywhere

Philadelphia’s Earth Day observance would turn out to be so popular that the event morphed into an entire week. Yet even among the illustrious guests he’d assembled, the rangy and mustachioed McHarg commanded center stage. On one day, standing in front of Independence Hall, he recited the Declaration of Independence; on the next—the actual Earth Day, April 22, 1970—he addressed 30,000 people packed onto Fairmount Park’s Belmont Plateau.

“Why must I,” he asked in his pronounced Scottish burr, “be the person who brings the bad news?”

The bad news was, of course, the newly recognized vulnerability of the Earth amid industrial pollution, urban sprawl, and natural degradation. McHarg would make a mission out of delivering that message, again and again. In 1969, he had served as a narrative voice of doom for the television documentary Multiply and Subdue the Earth, which premiered on Boston public television before gaining wider release in movie theaters. Outfitted in a trench coat and speaking from a neon-lit darkness—signs for gas stations and Donuts Please blazing behind him—McHarg practically spat out his thesis: “I wonder, when there are 100 million more of us by the year 2000, will our cities be sicker still, our landscape befouled? That’s likely to be so, mate, and the reason is simple. We are a man-centered society. We have never learned that we are a part of nature.” Going on to excoriate the “hotdog stands, the ticky tacky houses, the sterile core, the ravaged countryside,” he summed up: “This is the image of Anthropocentric man. He seeks not unity with nature but conquest—yet unity he finds when his arrogance and ignorance are still and he lies dead under the greensward.” Nearly three decades later in Quest for Life, he would poke fun at his starring role as “energetic, given to hyperbole and colorful language,” but noted that the film “remains remarkably topical. It seems that we have learned little.”

In the book’s preface, he described his own evolution from a landscape architect and city planner into an ecologist and activist: “My first concerns were local and small scale, next urban, then metropolitan, then for regions. Here, now at age seventy-five, it is the entire, improbable, unexpected planet that has become the central issue for me, and for you.” In the reports he produced for municipal and regional agencies, he regularly exhorted them to provide more open spaces in cities, to protect their natural lands, and to develop a considered response to natural disasters like hurricanes and floods—all now standard operating procedure in today’s planning world.

McHarg was busy with more than documentary narration and Earth Day planning in 1969. That’s also the year his seminal book, Design With Nature, was published. To mark its 50th anniversary, the Stuart Weitzman School of Design has launched the Ian L. McHarg Center for Urbanism and Ecology and over the summer mounted Design With Nature Now, a multi-faceted tribute that included a two-day symposium in June and three ongoing exhibits on campus.

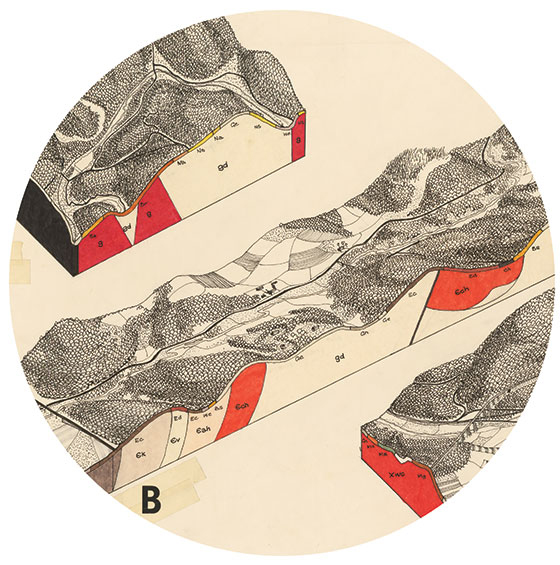

Design With Nature was a bestseller and cemented McHarg’s position as a public intellectual along the lines of Rachel Carson, whose Silent Spring (1962) had helped launch the environmental movement, and Jane Jacobs, who decried urban planning’s damage to neighborhoods in The Death and Life of American Cities (1961). By the late 1960s and into the ’70s, he was a regular on talk shows and the subject of profiles in magazines like Time, which lauded him as the “nation’s most visible apostle of using ecology for planning.” Yet he never became a household name in the way that, say, the architect Frank Lloyd Wright did. You can’t visit many of McHarg’s projects, since most weren’t realized. And his texts don’t make for easy reading. Design With Nature, for example, is laden with technical illustrations depicting the “layer cake” of water and land features that make up any natural site, and written in an erudite tone that melds the portentous with the courtly.

Within his own field, though, he was and remains a—perhaps the—central figure. “The things that Ian talked about 50 years ago are still fundamentally right and valid today,” observes Jose Alminana GLA’83, principal at Andropogon Associates, whose projects include Shoemaker Green outside the Palestra [“Gazetteer,” Nov|Dec 2012]. “And for those of us working in the field, his teachings have become second nature to the core of what we do. He gave an extraordinary gift to the profession by encouraging us to push boundaries and to insist on weaving nature into the built environment.”

McHarg arrived at Penn in 1954, charged with creating a new department of landscape architecture, and wound up creating one of the University’s most popular courses, “Man and Environment.” He is widely credited with establishing the leadership position in the field that Penn still holds. The department’s faculty and graduates—who now work at Philadelphia-area landscape architecture firms like OLIN and Andropogon, in regional planning offices like WRT, and at the zoo design firm CLR—have established the city as a prime locus for the discipline. Besides launching careers and sounding the alarm on environmental issues that are now so widely discussed as to seem overly familiar, McHarg’s design approach was also a forerunner of what became known as a geographic information system (GIS)—a visual layering, or mapping, technique (now computer-aided) that allows designers and scientists to combine and analyze complex data sets. “At the time, if I had gone to Harvard or Berkeley to study landscape, I would have been looking at stuff like exterior design and layouts, outdoor furniture, and plant selection,” says Dennis McGlade, GLA’69, a partner at OLIN, where his projects have included grounds for the National Gallery of Art in Washington and the J. Paul Getty Center in Los Angeles. “At Penn, McHarg was teaching us the underpinnings of topography and putting the site in its greater context.”

With the empirical method McHarg developed “you could examine the geology of a piece of land—and after analyzing the specifics of its soil, water, vegetation, slope, and micro-climate—at least in theory determine the right use for that land,” elaborates Richard Weller, the Meyerson Chair of Urbanism and professor and chair of landscape architecture, who is also co-executive director of the McHarg Center. “He believed that regions have their own internal logic—the Piedmont looks the way it does for a set of specific reasons, the prairie for another set—and that those forces provide you with clues as to how you develop and use the land in that place. To this day, his method is used in making basic planning decisions.

“Just about every contemporary landscape architect has to measure themself against McHarg, somewhere along the spectrum from profoundly rejecting his manifesto to devoting yourself to him.”

Early on, Weller was in the rejection camp. “I began by utterly loathing the guy,” he says. “For me, this wasn’t creativity or design: his maps were mechanistic, they meant nothing, they seemed utterly useless. I was much more interested in self-expression, in design. I’ve come full-circle and am doing much larger-scale work, so have come to appreciate the brilliance and elegance of the methods. The issues he addressed, too, have become more, not less, important. He had the technology, he had the polemics, and he had the personality.”

At its core, Design With Nature “is about saving our planet—not by controlling nature but by learning from it and adapting our civilization accordingly,” says Frederick Steiner GRP’77 G’86 Gr’86, dean of the School of Design and the McHarg Center’s other co-executive director. Steiner still remembers when he first encountered the book. He was making his own Earth Day preparations at the University of Cincinnati, where he was studying graphic design, and “went to buy some books on the environment,” he says. “I found Silent Spring, I came across something by [conservationist] Aldo Leopold, and I saw one with the word Design in the title, which immediately got my attention.”

Steiner, who already had his sights set on Penn for graduate school, also heard McHarg speak in Cincinnati at a conference of civil engineers. “He was hilarious,” he says. “He told them he had blown up bridges in World War II and he’d love to blow up everything they made. They gave him a standing ovation.” Once Steiner made it to Penn as a student, he and McHarg formed a lasting friendship, and Steiner would later help shape and edit A Quest for Life.

Growing up between the wars in Clydeside, in suburban Glasgow, McHarg experienced both a “beautiful and powerful landscape [and] a mean, ugly city,” he writes in the book. Nature meant freedom while the city offered only “repugnance,” “challenge,” and a “testament to man’s inhumanity to man.” He recalls a youth spent idling on long walks, nurturing a prize-winning talent for drawing, and indulging a propensity for gardening. At 16, frustrated with high school, he made an appointment to see a career counselor who “drew from me descriptions of the walking trips in which I engaged every summer, farther and farther from Clydeside into the lochs and mountains of western Scotland. Then he said, ‘Have you ever considered landscape architecture?’ I had never heard of it.”

The counselor put him in touch with a landscape architect. During the ensuing apprenticeship, McHarg learned about the “set pieces” of the business—“lawn, herbaceous border, rose garden, wildflower garden, tennis court, swimming pool”—and withdrew from high school to enroll in a few art and agriculture college courses. He was eventually allowed to design and execute some garden exhibits for the annual Highland Show, an agricultural competition along the lines of an American state fair. “My career was beginning to take form,” he writes. “But this career would be delayed. I had to embark on another—as a soldier.”

McHarg’s Presbyterian upbringing and exposure to prominent pacifists like Mahatma Gandhi initially left him conflicted about enlisting. The “barbarity of Mussolini’s son bombing Ethiopian natives, the insolent arrogance of Hitler, and the futility of appeasement” shifted his opinion. He became a paratrooper and eventually reached the rank of major. He also grew a “spare and unconvincing” mustache—more fully grown, it would become his trademark—and emerged from the war a considerably more worldly figure. “My travels could hardly have been improved had they been designed for my education,” he observes.

Upon his demobilization in 1946, he determined it was time to resume his training to become a landscape architect, and further determined he should receive it at Harvard, which in 1900 had established the world’s first program in the discipline. But it was a graduate curriculum and McHarg was in possession of neither a high school nor a college diploma. What he did possess, apparently in spades, was chutzpah. Remembering a motto he had learned as a soldier—“bullshit baffles brains”—he drafted a letter to the chairman of the department: “I propose to begin studies towards a Master in Landscape Architecture with effect from September 1946,” it read, according to his memoir. “Please make the necessary arrangements.” The response came: “Dear Major McHarg: We are so proud that you chose Harvard.”

His four years there would net him not only a wife (the multilingual, multitalented Pauline Crena de longh, a Dutch-born Radcliffe student) but a degree in … city planning. “The [landscape architecture] faculty was committed to the interwar tradition of gardens for the rich,” he writes. “[T]heir visions were small as were their scale; they were without distinction, an anomaly in a great university.” City planning, by contrast, offered him training in a “systematic view which allowed me to see artifacts as products of time, process, culture, and environment.”

The switch in focus would provide another stroke of good fortune for the young McHarg, introducing him to G. Holmes Perkins, then chair of the city planning department. Several years later, after he became dean of Penn’s School of Fine Arts, Perkins would recruit McHarg to teach city planning and to develop a new graduate program in landscape architecture at the University.

McHarg’s first order of business in that effort was to confront the challenge of the “low esteem of the [landscape architecture] profession, vis a vis architecture in the academic community, and in society at large,” he writes. “With the notable exception of Harvard and the University of California at Berkeley, landscape architecture was usually an undergraduate curriculum in land grant colleges. Moreover, these departments were often within schools of horticulture or agriculture, and waifs in these. Such departments did not attract the brightest students.” He also groused about Penn’s “modest” commitment and his starting salary of $5,000. “Such appointments are notorious. The rule is, up or out. I had three years.”

McHarg set to work by meeting the right people in the right places—like Laura Barnes, who, he observes in A Quest for Life, “actively disliked the paintings” assembled by her husband, Albert M1892, in their Merion, Pennsylvania, home, later to form the Barnes Foundation collection. “She recoiled from acres of Renoir and Rubens flesh,” he writes. “Her passion was trees. She had created an excellent private arboretum.”

Tall, handsome, and by many reports a charmer with the ladies, McHarg must have made a good impression. As they enjoyed afternoon tea in her garden, Mrs. Barnes declared that she would pay the tuition of eight students, along with a stipend for their daily expenses. “[T]his generous gift made possible the search for the superior candidates who held degrees in architecture,” McHarg recalls. “An advertisement was written and published in every architectural magazine in the world … The response was marvelous from Britain, Norway, Australia, Turkey, India, Sweden, the Netherlands, and elsewhere, but not a single American applied.” The reason, he posited, was because the international architectural press of the time acknowledged the significance and practice of landscape architecture; the American media did not.

As the years proceeded, the program came into its own and McHarg began emphasizing his burgeoning ecological leanings, both academically and professionally. In the late 1950s, he conducted a study for the Urban Renewal Administration (a precursor to HUD) called “Metropolitan Open Space from Natural Processes,” which identified waterways, forests, woodlands, and agricultural lands in the Philadelphia metropolitan region and recommended prohibitions or limitations on their development. In 1959, he initiated his signature course, “Man and Environment,” bringing in guest speakers such as anthropologist Margaret Mead and historian Lewis Mumford. The course also helped shape a TV talk show McHarg hosted on CBS in the early ’60s called The House We Live In, in which he interviewed intellectuals from a variety of fields.

In 1963, McHarg entered a professional partnership with Penn planning professor David A. Wallace. (The firm that emerged would be called WMRT, now WRT.) But right up until he was forced to retire as department chair after reaching the age of 65—per the university’s policy at the time—he vigorously promoted his department. Elliot Rhodeside GLA’69, a principal at Rhodeside & Harwell in Alexandria, Virginia, recalls a presentation McHarg made to his class of industrial design students at the Philadelphia College of Art. “He told us about landscape architecture and how he was creating a multidisciplinary approach to it at Penn. His final words to us were that he wanted biologists, soil experts, and people like us, artists and designers.” And once Rhodeside entered the Penn program, McHarg offered a “grander way of looking at the field,” he says. “He wanted us to take real pride in the profession we were choosing, to understand that it was a noble endeavor that went way beyond planting shrubs and trees.”

Other alumni who have gone on to successful careers in landscape architecture are also quick to acknowledge McHarg’s influence.

“I continue to take from him the audaciousness, that interest in big issues,” says James Corner GFA’86 GLA’86 [“The Transformer,” Nov|Dec 2012], principal of James Corner Field Operations, the designer (most famously) of New York’s High Line, and a former department chair himself.

“Ian was always concerned about the size of the sheet of paper that you were using to solve the problem,” adds OLIN’s McGlade with a chuckle. “He liked design but he was really interested in big ideas that investigated context and the natural and cultural dynamics. For me, that’s what the Penn experience was about—trying to approach projects with a really big piece of paper.”

McHarg wasn’t alone in providing heady company for design students. “You have to remember that in the late ’60s, there was all this fermentation of new ideas,” McGlade adds. “Edmund Bacon was teaching planning, Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown and Louis Kahn [were] teaching architecture—I mean, it was the Athens of the built environment.”

As he leaves the Annenberg Center after the opening lecture of Penn’s Design With Nature Now symposium in June, Peter Helmetag GLA’85, who had traveled from Vermont for the weekend of events, recalls McHarg the professor as “crusty, always with a cigarette hanging from his mouth. He could be harsh—but he was very charismatic.” Crossing College Green and approaching the plaza outside of Meyerson Hall, he gestures toward the much-maligned structure that houses Penn’s design school. “McHarg hated that place,” he says. “Every time he walked in, he’d give this sort of exaggerated sniff and say, ‘Hmmm, smells like an engineer designed it.’”

(At the time of the building’s construction in the late 1960s, McHarg was vocal in joining the School of Fine Arts students and faculty to protest the Brutalist-style building, which was perceived both as a grab of open space on campus and a snub of Kahn, who was passed over as architect.)

Along with Helmetag (and McGlade, Alminana, Corner, and Rhodeside), some 400 of McHarg’s former students, colleagues, and disciples came to campus from around the globe to celebrate Design With Nature. “The book became kind of a bible for the field,” says Weller. “It was the first book they gave students in every landscape architecture department in the world.”

Writing during a time when excitement over space exploration was at its zenith—the 1968 “Earthrise” photograph taken by the crew of Apollo 8 had enraptured millions—McHarg used the device of an astronaut who observes the Earth from above and wonders if man and his cities are a kind of planetary disease. (He credits the writer Loren Eiseley Gr’37, professor of anthropology and history of science at Penn, with first conceiving of the image.) Alas, “his persuasion helps no one,” McHarg declares. A second metaphorical figure who periodically shows up—the deluded naturalist whose “imagined Utopia cannot be found”—also isn’t much help. It’s the “ecological view [that] offers an invaluable insight,” McHarg concludes. “It shows the way for … realizing man’s design with nature.”

Design With Nature began as a self-published effort, with McHarg handling direct mail sales from his home. He sold a few thousand copies before an imprint from Doubleday expressed interest in taking it on. Eventually it sold hundreds of thousands of copies and was translated into Chinese, French, Italian, Spanish, and Japanese. In Quest, McHarg bragged that it “has been described as the most widely used text for architects and landscape architects,” then added, “I have observed no effects on the former.”

Canonical it may be, but the title has gone in and out of favor over the decades, Weller points out. “There was a reaction against it during the ’80s, for instance,” he says, “in the sense that you couldn’t use his method to do the small, more designed projects that we do in cities, where geometry and color and form play a larger role.”

In Transects: 100 Years of Landscape Architecture and Regional Planning at the School of Design at the Universit of Pennsylvania (2014), Weller and coauthor Meghan Talarowski trace how the chairs who followed McHarg have reflected various trends in the field. His immediate successor, Anne Whiston Spirn, sought to balance his scientific predilections and return design to its place at the table; she was followed by John Dixon Hunt, an English landscape historian who pushed the department toward a more theoretical and contextual direction. Corner further explored landscape’s role in urban environments, while under Weller’s tenure, the emphasis has shifted to urbanization and ecological threats on a global scale [“Gazetteer,” Sep|Oct 2017]. These characterizations are simplifications, of course, but throughout the decades, there’s no doubt, as Corner observes, “that while each chair gave each era a distinctive feel, it was Ian who laid the foundation for everything that came after. He’s always there.”

That’s the thinking behind the title exhibit of Design With Nature Now, exploring 25 ongoing or completed projects—in the US and places like Africa, China, Europe, and New Zealand—that take inspiration from McHarg’s teachings and extend his legacy in some fashion. One of the projects is Corner’s master plan to turn the world’s largest landfill, Freshkills, into a 2,200-acre park, which seems particularly emblematic of McHarg’s work. The idea isn’t unprecedented, but it’s never been realized on this scale, nor carried with it such an ambitious program to create a new and viable ecological site from scratch (rather than, say, an adventure playground or skate park).

Freshkills began as a “temporary” garbage dump that opened in 1948 on Staten Island, NY, and grew larger and larger until—hemmed in by residential neighborhoods and a shopping mall—it was finally shut down in 2001. Soon thereafter, Field Operations was brought in to design a regenerative project with a timeline of 30 years. Several small parcels have already opened along the site’s edges and the first interior phase, a 25-acre piece featuring paths, a native seed farm, picnic lawn and observation areas, is projected to open within the next year.

Ellen Neises GLA’02, who currently is executive director of PennPraxis and teaches in the landscape architecture program, served as project designer and manager for the project while at Field Operations. A former winner of the McHarg Prize for Excellence in Contemporary Ecological Design, she recalls the “sense of endless possibility” that she, Corner, and their team felt while climbing the now-capped mounds of household garbage and taking in the views of the Manhattan skyline. “You can look at what happened as a loss, sure, but you can also feel very hopeful about its resurgence,” she says. “It’s being developed into a gorgeous, high-performing wetlands; there’s already an emergence of new wildlife and plant life, there’s a sense of a beautiful life cycle that is being engineered into a recreational area of the kind that isn’t easily available to New Yorkers.”

Ultimately, McHarg was a voice who argued that landscape architecture deserved a much bigger stage. Freshkills, and the other projects selected for the exhibit, go beyond designing in consort with nature to literally using it as a tool. They are more than sustainable—they are regenerative. And that, no doubt, would make the testy Scotsman very happy.

JoAnn Greco is a frequent Gazette contributor.

One Planet, Three Exhibits

As part of Design With Nature Now, Penn Design has organized a trio of exhibits that examine McHarg’s legacy. All three are on view through September 15.

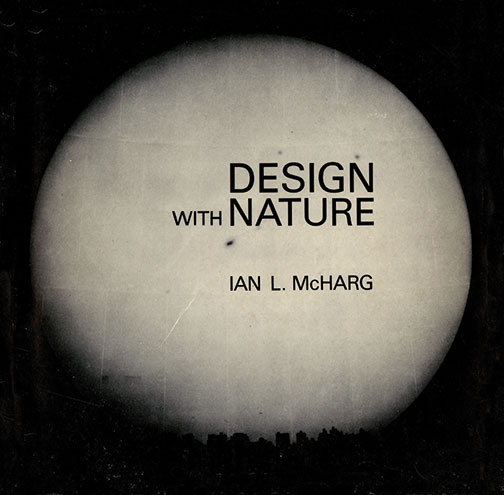

Ian McHarg: The House We Live In at Kroiz Gallery, Architectural Archives. Papers and artifacts—including the huge wall charts that resulted from Penn students’ studies of regions like the Delaware River Basin—from McHarg’s personal collection.

Laurel McSherry: A Book of Days at Arthur Ross Gallery. An affiliated faculty member at the McHarg Center, McSherry explores the nature of time and place through a series of maps, prints, photographs, drawings and video produced from her walks around Glasgow.

Design With Nature Now at Meyerson Galleries, Meyerson Hall. This global survey of 25 projects that are pushing the envelope of ecological design includes not only Freshkills Park, but a master plan for the Los Angeles River (OLIN and Frank Gehry Partners), GreenPlan Philadelphia (WRT, with inspiration from Whiston Spirn’s 1980s work in West Philadelphia), and the master plan for Qianhai Water City (Field Operations).

In addition to the two-day conference, which offered personal reminiscences and peeks at some of the 25 projects that make up the title exhibit, several tours and lectures are also forthcoming, as well as a book from Lincoln Institute of Land Policy that documents the exhibits and includes essays by some of the conference’s presenters, including James Corner, Laurie Olin, and Anne Whiston Spirn. —JG