After 40 years, a Johnny Appleseed of jazz signs off.

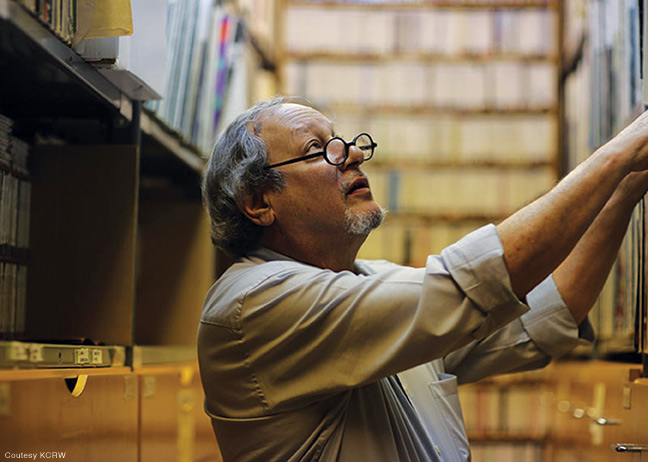

His colleagues call jazz DJ Bo Leibowitz C’67 the “last of a breed,” a “station treasure,” a “man with a mission.”

“His taste is uncompromising and he knows an incredible amount about the music,” says retired KCRW music director Tom Schnabel, who first put Leibowitz on the air in 1979.

Ever since then, Leibowitz spiced up the airwaves of the Santa Monica, California, public radio station with a show called Strictly Jazz —a smart and mellow jam session that celebrated the greatest jazz talents and tunes of the 20th century, while also tapping into contemporary composers/improvisors he cites as “keepers of the flame.”

The Indiana-born Leibowitz feels a kinship with “one of our state’s folk heroes—Johnny Appleseed. You’ve got to keep seeding the fields, spreading the joy,” he says.

Until suddenly, you can’t. In March, after 40 years, Leibowitz reluctantly signed off and hung up his headphones for the last time—with not even an on-air goodbye. “I’ve been having health problems and it has affected my on-air performance,” he says. “Better to go out swinging.”

Leibowitz’s four-decade run at the station was “unprecedented,” says the station’s executive producer for music programming, Arianna Morgenstern. “He’s done it out of a place of love. I don’t know anyone else who’s so dedicated. … Bo is irreplaceable.”

When Leibowitz first took to the airwaves, KCRW was “this little low-watt station with a 10-mile reach, playing classical all day, jazz all night, and I was on in prime time,” he recalls. Now with a much stronger signal and online presence, KCRW is one of the nation’s leading tastemaker stations for contemporary music. The downside? His sophisticated sonic soiree was relegated to a “wee small hours of the morning” time slot on Saturdays from 3 a.m. to 6 a.m. PST.

“But thanks to the internet, you could listen to it as an on-demand podcast all week long,” Morgenstern points out. And the livestream at kcrw.com was agreeably timed for early rising listeners on the East Coast (where this writer seldom missed a broadcast) and in Europe, where friends of Leibowitz’s British-born wife Rosemary could tell their smart speakers to “play KCRW–Santa Monica” and enjoy his musical buffet over brunch.

Even late in the game, Leibowitz treated each show as a special event. If an artist he admires was having a significant birthday, he would celebrate it with a tribute. Should a noteworthy player or composer pass on, he or she might get a better send-off on the radio than at the funeral. “It’s terrible to say, but when someone dies, it’s really energizing to me,” he confesses. A number of those tribute shows are archived and available for online listening.

Leibowitz was introduced to jazz by his father, Irving, a newspaper writer and editor. He had “an Earl Wilson-style daily politics and culture column at the Indianapolis Times,” Leibowitz says, citing the nationally syndicated columnist who chronicled the entertainment scene in the postwar years. “Dad grew up in the swing era, lived down the street from [drummer] Buddy Rich in Brooklyn, then got into the news business without going to college. Back in those days, they sent records to the paper and he scooped up the jazz titles, which I first got into when I was 15. Guys like Charlie Parker, Miles Davis and Art Blakey.”

Leibowitz “took to the music like a duck to water,” he recalls. “Everything snowballs. You hear somebody soloing on a record that’s good, you go seek out more of his stuff.” He taught himself piano after hearing composer Henry Mancini’s score for the private-eye TV show Peter Gunn, “banging out the theme in the basement, driving my mother crazy.” And he quickly developed a fascination with the history of jazz—“how everything evolved from New Orleans, spread up to Chicago and Kansas City, and eventually to New York, after they closed down the whorehouses in Storyville and the musicians migrated north.”

Leibowitz arrived at Penn in 1963. He was known as Alan then—but so were lots of others, “nine just in TEP, my fraternity”—so after an initial period as “Leibo,” he became known as “Bo.” (He did publish a guide to recordings under the name Alan Leibowitz, though.)

After four years, he left Penn with a new name—but without a diploma, owing to “several incompletes hanging,” he says. “I wasn’t much for going to classes.” He spent most of his time “reading, listening to music, and going to the movies,” he adds. “In the era of the Beatles, jazz albums had fallen out of favor, so I could scoop them up for cheap at campus shops. I checked out the jazz clubs—Pep’s and the Showboat. And there were a couple bargain movie houses on Market Street, frequented by homeless people, that played art movies by Buñuel, Renoir. Went there a lot.”

His one A—in “a creative writing class taught by Emily Wallace”—did somewhat point toward his future. “I wrote a silent movie script, scored to an 11-minute recording of ‘You Are My Sunshine’ sung in a compelling, dirge-like fashion by Sheila Jordan with the George Russell Sextet.”

He split the next 14 years after Penn evenly between New York and Boston. One job in New York was at FM Guide, “a radio equivalent of TV Guide,” where he wrote about jazz and scored front row seats to shows by the likes of Thelonious Monk and Bill Evans. “They really made me a piano-jazz lovin’ guy,” he says. “I even named my son Evan.” In Boston he co-ran BoJo’s, a record shop on Harvard Square, and got his first gigs as a DJ. “I did shows on WBUR, guested a couple times on WGBH, and took over a show on the MIT radio station WTBS—before they sold the call letters to Ted Turner—and found out I was pretty good at it.”

On a trip west he dropped one of his airchecks on Tom Schnabel, who was a “friend of a friend,” and was hired immediately. At the time KCRW was a “10-person operation in the basement studio of a junior high school across the street from Santa Monica College, which held the station’s license,” he says. The station had no money to pay him—“and wouldn’t until seven or eight years ago,” he adds—so Leibowitz also held a longtime day gig as a court reporter, “mostly transcribing matters before the US Securities and Exchange Commission.”

Today, KCRW is a massive undertaking with three simultaneous content streams and more than 100 employees, plus volunteers, housed in a brand new 30,000-square-foot operations center. While most everybody else pulls content from a computerized, digitized base of music for their shows, Leibowitz stuck with the station’s huge collection of vinyl records and CDs, supplemented by treasures he brought in from home.

It was not easy getting up for work at 1:30 in the morning, Leibowitz says, and the recent embarrassment of sleeping through an alarm and missing half his shift—“probably from the meds I’m on”—was a factor that drove him to resign. But “hopefully it will carry on,” he says. “People who say ‘jazz is dead’ just aren’t listening. It will never die. It just needs exposure.”

—Jonathan Takiff C’68

Ed. note: Alan “Bo” Leibowitz C’67 passed away on June 3, 2019.