A rising design firm combines innovative ideas and social impact.

Clad in black and sporting slightly graying locks, architect Marc Kushner C’99 considers what it meant for him to grow up in a family of real estate developers. (To get that lineage out of the way: Marc’s father is Murray Kushner C’73 L’76, who built his own real estate empire after splitting from his brother, Charles Kushner—father of White House advisor Jared—in the early 2000s.) On one hand, he says, his upbringing instilled in him a love of buildings. On the other, the family “really didn’t think of architects as [being] on the same side. They were just another box to be checked off for a project.”

Kushner’s “black sheep” path was in part inspired at Penn by David Brownlee, the Frances Shapiro-Weitzenhoffer Professor of 19th Century European Art, who he says helped him understand the power of architecture. “He had a way of turning these inert objects into things that had stories to tell about the past and that could act as harbingers of what was coming next, socially,” Kushner recalls. “It was like candy. I just gobbled it up.”

Kushner was a political science major at Penn, but architecture got mixed in fairly early on. Following an internship at the Clinton White House during his sophomore year, he wrote a paper on the intention behind the design of the capital’s French Second Empire style Old Executive Office Building, and ended up creating a second individualized major focusing on “Vernacular Architecture as Cultural Artifact.” Having decided he might want to practice architecture after all, he went on to Harvard for his master’s degree.

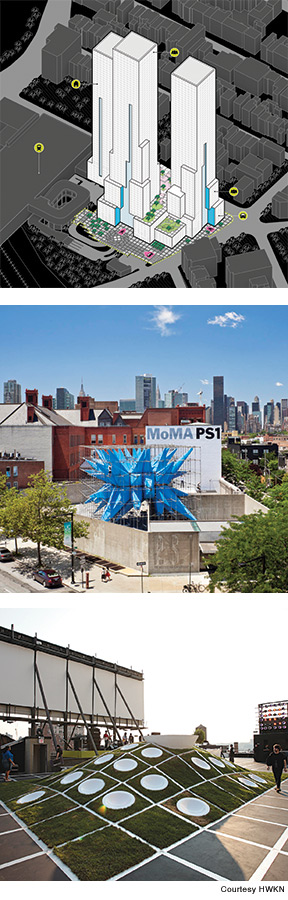

Today Kushner is the co-founder and co-principal, with Matthias Hollwich (a frequent lecturer at PennDesign), of Hollwich Kushner (HWKN), which employs 35 people. From the firm’s offices on the 14th floor of a classic 1960s curtain-wall building in lower Manhattan, Kushner has a view across the Hudson River to Jersey City, where the firm’s latest—and by far biggest—project is rising: Journal Squared, an amenities-rich, mixed-use development consisting of three evenly gridded skyscrapers offering 1,800 rental units, designed in collaboration with Handel Architects. The client is KRE, the firm helmed by his father—though they won the commission through an open competition.

Another major project under construction is 25 Kent, the first speculative office property to be built in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, in 50 years. And HWKN was also the lead designer on the renovation/reconfiguration of the University’s Pennovation Center flagship building [“Gazetteer,” May|Jun 2015], which opened in October 2016. In 2017, Fast Company lauded that design for “making adaptive reuse sexy” when it named HWKN one of the top 10 most innovative architecture firms.

Kushner and Hollwich were passing acquaintances when they decided to collaborate in a competition to design a theoretical skyscraper. They didn’t win, but “we saw we were simpatico about the process and the idea of using architecture to address social issues. And we liked each other,” says Kushner. “So we decided to start a firm, even though we knew nothing about running a business.”

They quickly scored a handful of small commissions and then landed their first major one: a branded pop-up event space for Mini, the British car maker. They created a grass-covered hill set in the middle of a Hell’s Kitchen rooftop, which for 10 days welcomed millennials who rode a rickety elevator to indulge in yoga classes and sustainability lectures while taking in the views.

The gig itself was perfect, allowing HWKN to do the kind of community-focused design the principals were interested in, backed by the financial leverage of a large corporation. The timing—the summer of 2008—was less ideal.

While the ensuing economic meltdown was a setback, the young firm pivoted in new directions. They launched Architizer, a web portal linking architects, their projects, and the manufacturers that bring those projects to life. According to Kushner, 85 of the field’s top firms are currently members of the network, and the site’s A+ awards—billed as architecture’s top awards program—draws about 4,000 entries annually. Architizer is key to HWKN’s agenda, Kushner says. “We believe that better information makes better buildings make better cities.”

The recession also fostered opportunities for HWKN’s continuing interest in conceptual work like 2017’s “New(er) York: An Obsessive-Compulsive Study of the City We Love,” which reimagines the Big Apple’s Art Deco landmarks as if they were designed with contemporary materials and methods. Kushner compares such efforts to Google’s company policy allowing employees to spend 20 percent of their time on side projects.

And those conceptual exercises can lead to real-world payoffs, as happened when HWKN was selected for the breakout Young Architects Program sponsored bythe Museum of Modern Art. “After years of entering competitions, when we finally won it was for something that actually mattered,” Kushner says with a laugh.

The victory gave HWKN the chance to exhibit in the outdoor space of PS1, MoMA’s outpost in Queens, for the summer of 2012. Their project, “Wendy,” was a spiky blue form that resembled the word-balloons reserved for POW! and BAM! in superhero comic books. Made of nylon fabric treated with a high-tech spray designed to attract carbon dioxide particles and purge them from the atmosphere, Wendy’s environmental impact was the equivalent of removing 200 cars from the roads each day.

“Through their construction and their operations, buildings are the world’s largest polluters,” Kushner points out. Wendy, on the other hand, was a fun-looking and approachable piece of architecture whose mission was to heal, not ruin, the environment.

The added visibility helped establish Kushner and HWKN as a major voice on where the field of architecture could be headed. In 2015, he published The Future of Architecture in 100 Buildings (Simon & Shuster/TED), and his companion TED talk, “Why the buildings of the future will be shaped by … you,” has close to 1.5 million YouTube views. Architecture Can! in which he and co-author Hollwich review the firm’s work from its first decade, 2008 to 2018, came out last October from Images Publishing Group.

“There’s a big push to have architects involved in civic life and to give the built environment a voice,” Kushner says, but he sees the possibility for an even broader social role for the field. “I haven’t really formalized it, but I think architecture could be used as a lens to understand the polarization we see in the current political climate,” he adds. “There’s something about the places where Americans spend their time, I think, that adds to these divisions—density versus sprawl, that kind of thing. If there is power in architecture like I believe there is, then maybe this is a way we could be using it.”

—JoAnn Greco