A yearlong series of exhibitions and programs draws attention to the iconic poet’s later years.

Walt Whitman (1819–92) towers over the canon of American poetry, his innovative free verse, romantic connection to Nature, and vision of radical democracy inspiring generations of acolytes. Hart Crane, Allen Ginsberg, and W. S. Merwin paid homage to him in their verse. Bram Stoker, who befriended him, may have modeled the hirsute antihero of his 1897 Gothic novel Dracula on the aging poet. A suspension bridge connecting Philadelphia and Camden, New Jersey, attests to Whitman’s enduring local impact, even though the naming process itself provoked controversy.

Whitman at 200: Art and Democracy, a yearlong regional project pegged to the poet’s May 31 bicentennial birthday, celebrates his continuing importance. Organized by the University of Pennsylvania Libraries with support from the Pew Center for Arts & Heritage, it features four artistic commissions and a variety of exhibitions, performances, poetry readings, and other programs. On the birthday itself, major events were planned at Philadelphia City Hall—with rocker Patti Smith and her daughter, Jesse Paris Smith—and at the Walt Whitman House in Camden.

The celebration “was meant to be multidimensional,” says project director Lynne Farrington, a senior curator at the Penn Libraries’ Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts. Aligning Whitman with contemporary preoccupations, it has touched on the poet’s concern with democracy “in light of the current political situation,” the connections between art and democracy, and Whitman’s status as “a gay hero,” she says.

Like the narrator of “Song of Myself,” Whitman at 200 contains multitudes: its more than 50 partners include the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Free Library of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Academy of Vocal Arts, and William Way LGBT Community Center.

One of Penn’s own events was an academic symposium, Whitman at 200: Looking Back, Looking Forward, which drew experts from around the country to the Van Pelt-Dietrich Library on March 29–30 for talks and a pop-up show of Whitman manuscripts, letters, early editions, photographs, and other rarities from the University’s collection.

Through August 23, the library’s Kamin Gallery is hosting another exhibition, Whitman Vignettes: Camden and Philadelphia, focusing on the poet’s later years and his ties to those two cities. Farrington, the exhibition curator, observes in her introductory label that scholars have become increasingly interested in Whitman’s late works, “influenced by disability and old age and reflecting Whitman’s changing views of American society and his place in it.”

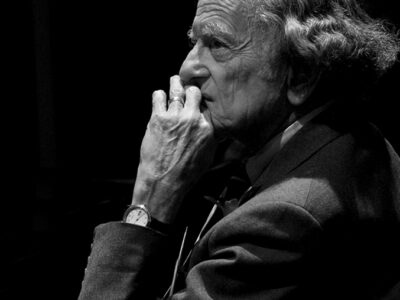

The symposium bore that out. In his keynote address, “Whitman Getting Old,” Ed Folsom, a professor of English at the University of Iowa, argued that—in terms of his continuing impact—he was not. “It seems that each year brings new discoveries,” Folsom said. “But there’s been a gradual … shift in our view of Whitman and his work, as if we’ve been searching for the Whitman who can address and respond to a growing cultural despair instead of the Whitman who spurs on an endless optimism.”

Folsom—who edits the Walt Whitman Quarterly Review, codirects the online Walt Whitman Archive, and edits the Whitman Series at the University of Iowa Press—suggested that the post-Civil War poetry expressed “in excruciating detail the feeling of being trapped in a failing body that confronts, rather than merges with, death.”

Michael Warner, a professor of English and American studies at Yale University, touched on similar themes in his talk, “Dying in Public: On Late Whitman,” calling the late verse a “poetry of infirmity.”In “Whitman’s Aesthetics of Paralysis,” Don James McLaughlin, assistant professor of 19th-century American literature at the University of Tulsa, discussed the impact of Whitman’s crippling strokes on his poetic practice, finding “an erotic dimension” and “a determination to embrace and even flaunt his paralysis.”

Other speakers addressed Whitman’s involvement with the printing process and its impact on his work. In “Printers of the Kosmos: Reimaging How Leaves of Grass Came to Be,” Matt Cohen, professor of English at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, explained how Whitman’s most famous collection changed from edition to edition through Whitman’s own edits and additions, as well as printing errors and subsequent critical misreading.

Some talks sought to put the texts in context. Meredith McGill, associate professor of English at Rutgers University–New Brunswick, connected Whitman to newspaper poetry of the 1840s. And, in “Whitman’s Poe,” Edward Whitley, associate professor of English at Lehigh University, situated the poet within the Bohemian culture of his era, while also pointing out references to Poe in his work.

In both the Vignettes exhibition and the symposium, “we wanted to look at later Whitman because he doesn’t always get enough critical attention,” Farrington says. “He’s using that period as a way of consolidating himself for posterity’s purposes, for his legacy.”

The exhibition showcases an expurgated English edition of Leaves of Grass; Whitman’s calling card, hair, and pencil; a list of attendees at a 1891 birthday party at his Mickle Street house in Camden; and Delaware River Port Authority documents related to the 1955 naming of the Walt Whitman Bridge. The opposition, apparently organized by the Catholic diocese of Camden, spawned mimeographed form letters objecting that the poet was “not great enough,” “boasted of his immoralities,” and “held Christianity in contempt.”

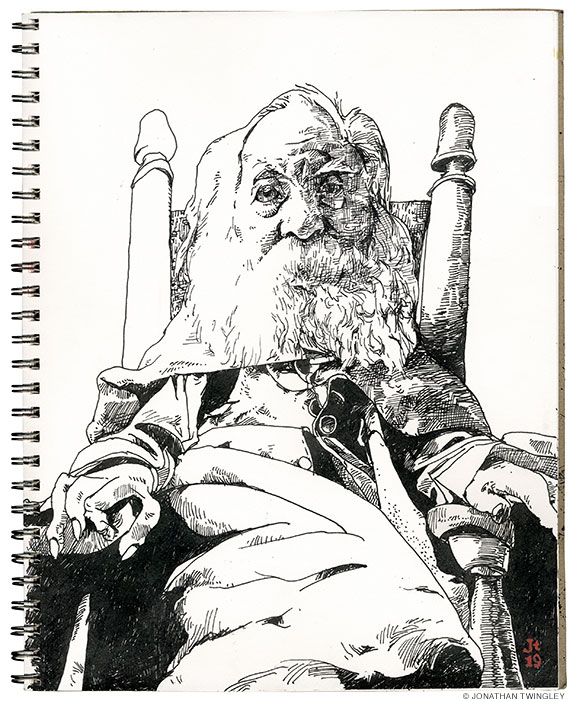

One highlight of the show is an 1887 portrait of the elderly Whitman by Herbert Harlakenden Gilchrist, whose widowed mother, Anne Burrows Gilchrist, imagined herself in love with Whitman before ever meeting him. The exhibition features correspondence between the poet and his admirer, who lived in England. “She fell in love with his poetry. She feels like Whitman is her soulmate,” Farrington says.

Despite the poet’s cautions that he was not to be confused with his verse, Gilchrist came to Philadelphia to live for a period of about 20 months, in 1876–78, Farrington says. Whitman was a frequent visitor. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the romance didn’t work out, but the two remained close friends, corresponding until her death in 1885. “It’s a complicated relationship,” Farrington says.

—Julia M. Klein