I have no idea if Dan Hoffman was a genius. But he was a hell of a teacher.

By Daniel Akst

Why Penn admitted me I’ll never know, for I was never a good student and had no obvious talents. When the day finally came, back in 1974, I took a subway from Brooklyn, a train from Manhattan, and then, at a discreet distance, followed a huge green duffel bag bobbing on the shoulder of a young man who looked like a student. Walking from 30th Street Station, we cut through Drexel—and had he gone no further I’d probably be an engineer today.

But he walked on, and so did I, until I found the Quad, to which I’d brought some clothes, far too little money, and only a single, all-too-burdensome gift. This wasn’t any particular ability, but rather a vocation, for I intended to be a writer. I still do. If any one person has been an enabler in this quixotic venture, it was a bushy-browed poet and Penn professor by the name of Daniel Hoffman, whose spirit has presided, no doubt uneasily, over my authorial life since.

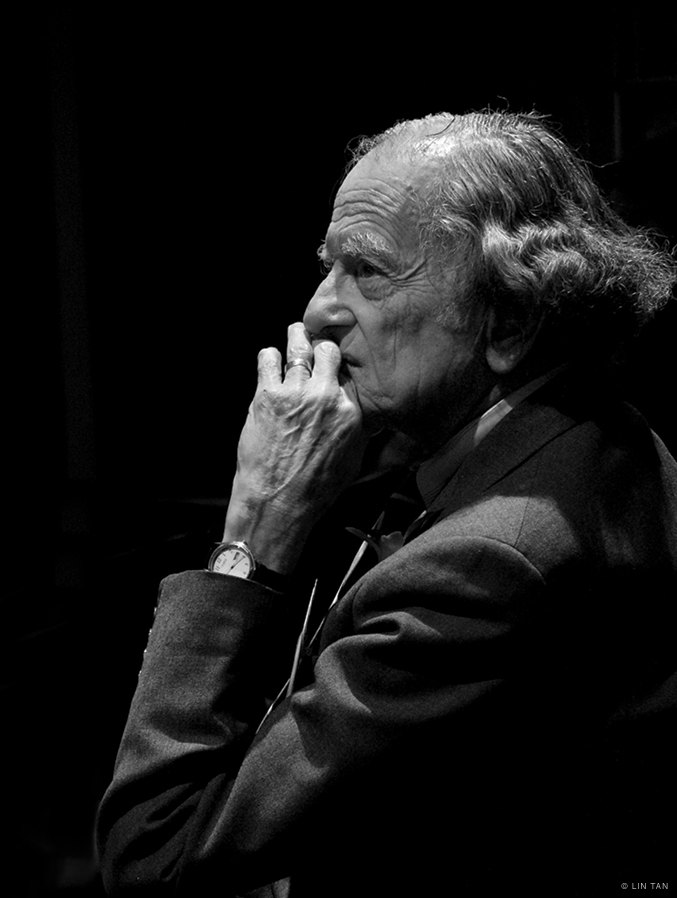

When my most recent book came out, I was disappointed that it was no longer possible to send him a copy. It’s been a decade now since an obituary in the New York Times pronounced him an old-fashioned man of letters whose versatility was so great that it undermined critical appreciation of his accomplishments. “He was as adept at free verse as he was with meter and rhyme,” his friend David Mason wrote in the Sewanee Review, “and he once said in an interview that ‘a poet, like a musician, should be in command of all of the possibilities of his instrument.’”

But surely more important than the 10th anniversary of his death, to admirers of the late Felix Schelling Professor of English Emeritus, is the centenary this year of his birth, and the lasting impact he has had. He was, in the words of poet Dana Gioia, “one of the finest American poet-critics of the post-war era.” He was a hell of a teacher as well.

I had a lot to learn before I would find that out. One of my earliest campus acquaintances was an Adams, and later a descendant of Ben Franklin became a housemate. The first girl I dated took me home to Rittenhouse Square and introduced me to her father and his elegant girlfriend, who seemed to be carrying on a brilliant impersonation of Katharine Hepburn. I thought I’d join the fun by doing Cary Grant, but some knowing voice stayed my jest. “Wait,” it whispered in my innermost ear, just like a modern poem, except in plain English. “Just wait.” And so I learned that night about the Main Line—and my own Philadelphia story had begun.

I had come to study literature and was soon ingesting towering piles of novels, intending someday to write piles of my own. But somehow, perhaps out of dyspepsia, I found myself captivated by poetry, where so much could be said in so few words. William Blake, I soon saw, was dead right about how you could “see a World in a Grain of Sand” and “Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand.”

It will be hard for today’s readers to imagine the cultural salience of poetry in the 1970s. A single edition of the Daily Pennsylvanian—on November 9, 1976—carried notices of upcoming appearances by John Ashbery, Adrienne Rich, and Dennis Brutus, all in a span of just three days. The Ashbery event in particular felt more like a visitation than a poetry reading. His book Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror, published the previous year, had won the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award, and the National Book Critics Circle Award.

Despite this seeming unanimity, he was hugely controversial for his idiosyncratic style, at once somehow vivid and opaque. He seemed to be inventing a form of poetry as he went along, a form impossibly obscure yet hopelessly enchanting, even if its roots—in Wallace Stevens, the French Symbolists, the visual arts, and our own commercial patter—were plainly visible. I was smitten.

Dan Hoffman wasn’t that kind of poet, thankfully. His passion for poetic tradition, his mastery of the craft, his critical labors, and his warm temperament blended to make him a superb teacher. I learned all this when he surprised me by admitting me to his graduate-level poetry writing seminar.

I entered this remarkable class as an anxious tyro. Among my fellow students, a doctoral candidate named Ed Hirsch Gr’79 went out of his way to solicit my worthless opinion and to share his own keen insights—kindnesses that I have recalled over the years as he’s become one of America’s leading poets and, today, president of the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. Susan Stewart Gr’78 CGS’03, another classmate, went on to poetry stardom too, and a career at Princeton. Hoffman acolytes from other classes who’ve achieved poetic glory, such as it is nowadays, include Carole Bernstein C’81, Geoffrey Brock G’90 Gr’96, Michael Jennings C’71, Marilyn Nelson G’70 [“Lady Marilyn’s Wing,” Sep|Oct 2008], Jay Rogoff C’75, J. Allyn Rosser G’88 Gr’91, and Gregory Djanikian C’71, former director of Penn’s creative writing program [“The Moment and the Poem,” Sep|Oct 2014].

Like poetry itself, Dan Hoffman was demanding yet inspiring. Stewart, in a Festschrift for his 90th birthday, said “he struck a perfect balance between pointed criticism and unfailing encouragement.” And his lessons would prove invaluable even though my literary destiny lay elsewhere. It was he who awakened me to the need to be concrete, to be alive to the sound of language, to respect the reader and economize accordingly, and perhaps most of all to be pragmatic—nay, ruthless!—about what works and what doesn’t.

An unflagging Penn partisan, Dan could be stern; knowing of my role at the DP, he let me have it privately when we published something he considered particularly dumb. But he seemed to take poetry more seriously than he took himself, and it wasn’t just his faint resemblance to Groucho Marx that gave such a strong impression of bridled wit. Despite his hawk-like gaze, he always seemed about to find something funny. And although this could be unsettling—one lived with the continual risk of provoking a barb—I nonetheless adored that in him, for I have never trusted anyone who lacked a sense of humor. At the very least, it’s a good sign in a poet; humor and poetry alike depend on metaphor, after all, which Aristotle in his Poetics called “a sign of genius, since a good metaphor implies an intuitive perception of the similarity in dissimilars.”

I have no idea if Dan was a genius; in my years since Penn, I drifted away from verse, unable to find much space in poetry between the baffling and the banal. But he certainly had a remarkable career. W. H. Auden chose Hoffman’s first collection, An Armada of Thirty Whales, for the Yale Series of Younger Poets, and Hoffman’s many subsequent books—of poetry, criticism, and memoir—included Brotherly Love, a book-length verse narrative about William Penn. In 1973 he became consultant in poetry to the Library of Congress, a job later renamed with the words “poet laureate.”

It’s been said that there are writers who teach and teachers who write, but in Hoffman typing and tutoring existed in blessed equilibrium. I recall Hirsch saying, as we waited for class to begin one day, that Dan “really knows what makes a poem tick,” a great line because reading a great poem can feel like holding a time bomb in your hands.

Bernstein recalls that as a student 40 years ago she thought poetic form was old hat, and Hoffman an intimidating figure. By the end of the semester things were different. “Because of the class,” she reports, “I’ve been writing formal poetry (in addition to free verse) ever since college. Several of my formal poems—including a sestina, one of the most difficult forms in English—made it into the flagship journal Poetry.”

Dan changed what mattered to me as well. During the years I spent in the shabby newsrooms that once produced America’s great newspapers, my old professor often visited, even if only in my imagination, where he goaded me to find a better word, to slash hokum and cant, or to rearrange shambling sentences lacking rhythm or energy. Nobody in those environs much cared about the way things sounded in the mind, but I did because he did.

One of the ways he instilled these sensitivities was by handing out a short poem in a foreign language along with a plain English translation. Our assignment was to render a suitably poetic English version, in the process encountering the tradeoffs between sound and meaning, feeling and fidelity. Bernstein recalls puckishly translating a line from Apollinaire which, in her version, seems a fitting last word on our old professor. “Let the night draw on, and the hours sound; / The days go by, and I stick around.”

Daniel Akst C’78 is the author of two novels and three non-fiction books. His work has also appeared in the Wall Street Journal, the New York Times and the Gazette, among others. He lives in New York’s Hudson Valley.

So good. Wish I could write like you.