A new show at the ICA uses text, photographs, and film to probe memory and the construction of identity.

In order to understand me, a complicity of the reader will be necessary.

—Jean Genet, The Thief’s Journal.

On a kitchen table in the ICA’s main second-floor gallery, flanked by two chairs, lies a copy of Burn the Diaries. Open the book of journal-entry-like essays and photographs, created by Moyra Davey for her exhibition of the same name. It begins with a discussion of blankness: of Jean Genet’s efforts to construct the story of his life, and his focus on the textures and hues of the blank paper on which he would write.

“The murkiness and ambiguities of a life take on weight and authority by virtue of the published document,” Davey writes. “Perhaps this is what Genet meant when he said there is more truth in the whiteness surrounding all those black characters than in the meticulously transcribed words themselves.”

The presence of Genet, the literary outsider who died in 1986, is almost palpable in Burn the Diaries. Passages from his interviews and books, including his 1948 The Thief’s Journal, prompt Davey to examine her own motives.

But, she stresses, it’s not necessary to read Genet in order to appreciate the exhibition, which also includes a 30-minute film and a series of photographs, many presented in the form of mailers addressed to galleries and friends. A Toronto-born, New York-based artist who probes in several media, she was alternately fascinated and repelled by Genet’s piercing observations and his propensity for “throwing disgusting things in your face” (as she put it in an interview with ICA chief curator Ingrid Schaffner during the show’s opening). Hooked by his interviews, she didn’t always finish his works of fiction.

The title of the book and exhibition refers to the dueling urges that animate a diarist. One is “the compulsion to scribble, the delusion that we can hold on to time,” Davey notes. “The inversion of this neurosis is the anxiety of being read, the fear of wounding, and, just as strong, the dread of being unmasked.”

Some of Davey’s entries ruminate over relationships, including her long, sometimes-competitive friendship with the late artist and writer Susan Kealey:

We shared books and dolls, before one day without a word she began having sex and was no longer a child, and not much of a friend. I was left in the dust, until the moment she said she hoped I would sleep with her boyfriend because he was so gentle, so caring, etc. I did, and I told her about it (a hasty, joyless affair at a drunken party) and she told me to fuck off.

Later:

Susan made a bonfire of all her diaries after B. broke up with her when she was only fourteen or fifteen; two years before she died, she shredded all her papers.

For all the text, Burn the Diaries is highly visual, and rooted in everyday reality. Creases slice across the photographs-as-mailers, which are affixed to the walls by pushpins. Bright rectangles of tape—green, fuchsia, tomato-red—add splashes of eye-caffeine that suggest punk-rock album covers. (Davey’s memories of Kealey include their shared love of Roxy Music’s first LP, Bryan Ferry’s record jackets with photos of statuesque women with “impossibly broad shoulders and narrow, cut waists”—and David Bowie’s “Jean Genie,” said to have been inspired by Genet.)

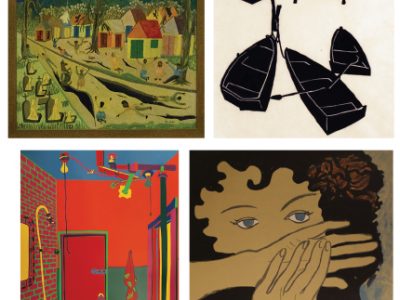

The images themselves range from cigarette butts on an urban window ledge, to a cracked porcelain relief of a jowly nun set in lichen-flecked stone, to some strikingly human-faced dogs, to a Wyoming landscape of hills and gullies, speckled with horses and an abandoned pickup truck. Scattered throughout are postmarked letters and envelopes and books, feasts of lushly textured paper, a young woman reading Genet’s Oeuvres Completes on the subway.

In the final entry of her essay, Davey writes:

When the 1 train goes elevated at 125th Street, sunlight from the east lights up an open book. For a brief moment, it is nearly impossible to look directly at the page; its surface is made blindingly white and radiant, all characters are blown out, erased.

Davey’s 30-minute film, The Saints, also has a dreamlike quality to it, heightened by images of snow falling on trees. (At her request, a comfortable couch has been provided for viewers.) Artists, friends, and family members discuss a passage from The Thief’s Journal in which Genet describes the increasing hysteria of a soldier searching for money he had hidden—which Genet himself stole—and reenact the scene in various forms around Davey’s apartment.

Alison Strayer, a writer friend of Davey’s who penned the second essay in Burn the Diaries, admits that she was “baffled, even irritated, by the pivotal role of Jean Genet” in the book. But, she adds, “I can see that, in a sense, he chose you.”

Burn the Diaries, the book, was published for the exhibition, which opened at the Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien (Vienna) this past February and in September at the ICA, where it runs through December 28. Schaffner, who organized the Philadelphia exhibition, contributed an essay to the catalogue.

“Like all writing, diaries consume time, energy, calories, turning life into nourishment for others,” she writes. “Close the book, set it back down on the table, where it turns into a small Surrealist object, a trompe l’oeil stack of books and papers with a plate smashed between the pages. A slim volume, for sure, but make a meal of it.”

—S.H.