Stephen Fried says we have Fred Harvey to thank for retail chains, Western tourism, and our model of exemplary customer service. He also suggests that his just-published book about the man and the “railroad hospitality empire” he embodied represents a new nonfiction genre: history buffed.

By John Prendergast | Photography by Chris Crisman C’03

Excerpt | Appetite for America

“Absurdly different,” suggests Stephen Fried C’79, when my choice of adjective—“wildly”—does not seem sufficiently extreme to encompass the narrative territory covered in the five nonfiction books he’s published since cutting his journalistic teeth at 34th Street as a student. Like his award-winning articles for magazines including Philadelphia (where he was on staff for many years and served a stint as editor), Vanity Fair, GQ, Rolling Stone, and many others, Fried’s long-form works feature exhaustive research, meticulous reporting, and a vivid sense of detail—but that’s about all they have in common.

Thing of Beauty, which came out in 1993, told the tale—pieced together from hundreds of interviews—of the rapid rise and swift descent into drug addiction and death from AIDS of late-1970s “supermodel” Gia. It was followed by Bitter Pills, a dense, somewhat sprawling investigation of the pharmaceutical industry and in particular the little-discussed dangers of prescription drugs. The New Rabbi explored the various dramas surrounding a suburban Philadelphia synagogue’s choice of a successor to a longtime, much-beloved spiritual and community leader, while Husbandry was a collection of personal essays, mostly in the ruefully humorous vein, about marriage, originally written for Ladies’ Home Journal.

Fried’s latest book—Appetite for America: How Visionary Businessman Fred Harvey Built a Railroad Hospitality Empire That Civilized the Wild West, published in March—blazes two new trails, taking him out West and into the past. It has been well received, with a prepublication notice in Publishers Weekly that praised its epic sweep, “[f]rom the battle of the Little Bighorn to the Manhattan Project,” and positive reviews in The New York Times and Wall Street Journal, among others.

Fried himself calls Appetite for America his most ambitious piece of work yet, and even suggests he may emulate its method in the future. “The other books were hard, each in their own way. But they grew out of some natural skills that I already had from writing for magazines,” he says. “To do a book this big, this broad, to be able to learn enough to write knowledgeably about each part of history, but still not become a nerd and make it really boring, I felt I was putting myself through, like, nine college courses. And now that I’ve done that, I feel, ‘Oh, what’s the next book that I could write that’s like this, that would take me through another period of history and make it come alive the way this period in history did for me.’”

As the length of Fried’s subtitle suggests, the Fred Harvey story is not widely remembered. Old-movie fans may recall The Harvey Girls, the 1946 musical that starred Judy Garland and featured the Oscar-winning song, “On the Atchison, Topeka, and the Santa Fe,” but the Harvey legacy lives on most vividly these days at the Grand Canyon, where the company managed the El Tovar Hotel and associated attractions when the South Rim of the Canyon was first developed. That’s where Fried and his wife Diane Ayres, visiting the Southwest back in the 1990s, first encountered his future subject.

“Fred Harvey’s portrait hangs in the main lobby” of El Tovar—which remains, Fried says, “the classic, the one you want to stay at” among the lodgings around the Canyon. “And in the room you get a little pamphlet that tells you about Fred Harvey,” he adds. “I’m not used to basing a lot of my career decisions on pamphlets in hotel rooms, but it was intriguing.”

After learning more at nearby Painted Desert National Park, where he found Fred Harvey written in giant letters on the gift-shop building, Fried decided Harvey’s story would make for a good magazine article, but found no takers. Americana wasn’t selling in the 1990s, he says, and travel magazines—the logical market for such a piece—were focused on the international scene. But Harvey stuck in his head, and so did the surreal image of the great hotel perched at the edge of the immense canyon. “When you go to the Southwest, you start realizing that a lot of what’s there was created by the Santa Fe Railroad and run day-to-day by Fred Harvey,” he says. “Fred Harvey took care of everybody there.”

Something about the intersection of romance and moneymaking struck him as essentially American. A person’s first view of the Grand Canyon is famously awe-inspiring, Fried says. “They look at the canyon, and it’s amazing. And I had that same experience. But I also said, ‘How the hell did this hotel get here?’

“That very much sort of drove this [book], because, even though the Fred Harvey story begins way before the Grand Canyon and continues way after, it still is the best example of the audaciousness—to build a train to the Grand Canyon so that people can see this thing?—and at some level it’s so commercial.”

Lunching with his longtime editor at Bantam Books to discuss possible follow-ups to The New Rabbi, which had come out in 2002, Fried waxed enthusiastic about all things Fred Harvey—so much so that she instructed him to drop the other projects he was considering and put together a book proposal, promising “to make it worth my while,” he says.

“And so we very quickly tried to access everything that was out there, did a proposal,” he says. “And then I dove in and really started exploring the story, which was much bigger and more complicated and more of a family saga and more multi-generational than I realized.”

Over the next five years, Fried interviewed surviving family members; examined diaries, correspondence, notebooks, and other documents; made excursions to former Harvey House locations; collected various items of Fred Harvey ephemera; squinted over decades’ worth of local newspapers from Harvey-served towns on microfilm; and combed through shelvesfull of old books for passing references to the family and firm, assisted by a team of student interns.

“I employ 10 students as interns. They get credit through [Kelly] Writers House,” he explains. “There were times when we had 300, 400 books from Van Pelt and other books that we had brought in from libraries all over the country because we saw somewhere that there was, like, one line in them that seemed to suggest a story either about Fred Harvey or related to the story.”

When one set of interns graduated, they would cart the books back to Van Pelt, check them out to the next group, and cart them back to Fried’s home office. “You have to be able to deal with primary sources. And the Penn students who were involved in this—there were four shifts in all—got a really interesting education.”

One of the interns, Jason Schwartz C’07, wrote an award-winning thesis based on research conducted while working on the book, Fried recalls. “He was the one who got stuck reading all the newspapers from the early years of Fred Harvey that were not digitized,” he says. “And he ended up writing a great history thesis on frontier journalism, based on the most amazing editor in Leavenworth, [Kansas, where Fred Harvey was headquartered] who was this guy who carried guns and shot a number of people.”

Fried sees his book as within a budding genre of nonfiction, in which writers trained in magazine journalism are taking on historical subjects previously handled, if at all, by academics. He offers as further examples Erik Larsen’s The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair that Changed America, set at Chicago’s 1893 World’s Fair, and Laura Hillenbrand’s Seabiscuit: An American Legend, about the iconic 1930s racehorse.

“I think that what’s been happening in these more narratively written, more journalistically written, I think more dramatically written, history books is very much a product of what [the writers] were doing before these books,” he says. “A lot of what we do as long-form journalists is read things that are really boring, but are interesting to us, and then try to figure out how you could write them interestingly and still have them be as accurate as the boring versions. I think of that as a magazine-y view.”

Fried even has a name picked out for this new genre: “I’m trying to get people to call it ‘history buffed,’” he says—adding that no one thought fashionista, a word he coined while working on his supermodel biography, would take off, either. While plenty of professional historians might dispute Fried’s view of their prose style, he certainly tells a lively, fascinating story in Appetite for America that conveys both the sweep of history and the granular detail of daily life through some critical decades in the nation’s past. (See the excerpts following this article for a sampling.)

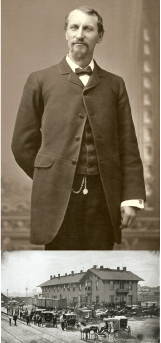

Fred Harvey the man immigrated to the United States from England in the 1850s and worked as a dishwasher and railroad agent, eventually coming to manage station lunchrooms and eating-houses. It was his peculiar genius to recognize that the catch-as-catch-can dining and lodging experience of train travelers (“[T]here was a reason the food was called ‘grub’ and the hotels ‘flea-bags,’” Fried writes) could instead become a model of comfort, efficiency, and quality with the right system—the Fred Harvey way.

Allying itself with the Santa Fe Railroad, the company managed hotels and restaurants—Harvey Houses—that offered both the finest of fine dining and more down-to-earth fare, with the best coffee anywhere for everyone.

“Fred Harvey was the first big customer-service business in this country, at a time when it was a totally manufacturing and railroad kind of world,” Fried says. “Any company that is grappling with these still-basic issues—they’re no different a hundred years later. Customer loyalty, quality control, employee loyalty, all these things that are required to make business work—the model, whether people know it or not, is Fred Harvey.”

In Fried’s telling, Harvey’s personality emerges as a compelling mixture of obsessive attention to detail and openness to innovation and continuous improvement, an attitude encapsulated in one of the many maxims he jotted down in the notebooks he carried on his travels: “Be cautious and bold.”

It was Fred’s son Ford, his successor as head of the company, who was responsible for creating Fred Harvey the brand when he made the fateful decision, after the older man’s death in 1901, of continuing to operate the company as if he remained at its helm. The firm name stayed the same—just plain Fred Harvey—and for many years thereafter routine correspondence continued to go out under the founder’s signature. (Fried tells a story about visiting a local museum, and having someone excitedly produce a letter “signed” by Harvey—in 1924; he himself purchased one of the rubber stamps used for signatures on eBay while working on the book.)

But if Ford was personally self-effacing, he was not at all shy about expanding the business, aggressively pursuing the venture at the Grand Canyon, which seemed risky at the time but would become the company’s biggest moneymaker as well as an enduring monument. That move led to Fred Harvey taking a leading role in promoting tourism to the West, and incidentally to helping preserve and grow respect for native culture.

“The fact that Frank Waters, who was an Indian historian, described the Fred Harvey system as ‘introducing America to Americans,’ which is a quote that you often see about Harvey, is really apt,” says Fried. “Obviously they were doing it for money. But they did have this messianic belief that, if you went and saw the Southwest and the Grand Canyon and the Indian pueblos, you would see America the way you were supposed to see it.”

Fried interprets this eager embrace of the West as a reaction to the strains of the Civil War. “Basically whatever people believed was wonderful about America was so compromised because of the Civil War that you needed a new way of organizing people’s love of America. And that’s why people became so fascinated with cowboys and Indians and with the West, because no one had fought over the West. And the Santa Fe and Fred Harvey did more [to promote that] than any other company.”

Ford Harvey also took the company beyond food service and into related retail businesses, including a chain of train-station bookstores. “If you go back and look at [Publishers Weekly] in the thirties, they’re all trying to figure out, ‘Well, how does Fred Harvey run these chain bookstores so well that they can sell the classics and the popular books of the day, and we have trouble with this?’” Fried says.

By the 1920s, Fred Harvey seemed poised to expand nationwide from its base in the Southwest, but the company fell on hard times as the century progressed. Personal tragedy played a role: Ford died suddenly in 1928 of the flu, and his son Freddie, a World War I hero and dashing aviator groomed to be the next Harvey to head the company, was killed in a horrific plane crash in 1936. The Great Depression, World War II (which turned the Harvey Houses into one big mess hall, eroding standards), and the decline of the railroads in the post-war era did the rest. By the time The Harvey Girls came out in 1946, the company was on its last legs, overtaken by fresher entrepreneurial spirits like Howard Johnson, Conrad Hilton, and others, though it would linger on until being sold in the 1960s. “[T]he mass marketing of American cuisine and Americana was left to other family businesses—and Fred Harvey’s America went on without Fred Harvey,” Fried writes.

Appetite for America is especially good at the nitty-gritty of growing and maintaining what even at its height was essentially a family business—an understanding Fried attributes in part to personal history. “I grew up in a family furniture business,” he says. “The fact that it turned out to be a family story was really great for me because that’s more what I do.”

As for the history part, the Fred Harvey story provided a unique prism through which to view the nation’s major events from the end of the Civil War to the dawning of the Atomic Age. “When you own the hotel and the restaurant, you see everything. You’re dealing with the bigwigs, and you’re also dealing with the person who wants to know why the bathroom stalls aren’t clean enough.

“And I figured, if I could document that, then you would have this thing where you were basically going back and forth between the waitress in Emporia, Kansas, and Teddy Roosevelt. So I looked for every little thing that I could find in clips, in archives, whatever, that would allow me to humanize the story. Because that’s real life.”

Though he’s pleased with the book and the response it’s getting, Fried isn’t actually sure about pursuing more history-themed books. “I’m at the phase right now, since people are liking this book, of thinking, ‘Okay, I’ll do that,’” he says. “But it is—everybody’s dead. And it is harder to write. It’s different to write a book when everybody’s dead. It’s lonely. And loneliness isn’t always that easy.”

A related issue with the “history-buffed” genre: Some may be on steroids, their narrative muscle bulked up with unwarranted speculation and fictional stagecraft. “I do look at some of these history-buffed books and then go back and look in the notes and ask, ‘Where did you get this? Did you just kind of fill in all the blanks, or did you have some of it?’” says Fried, who describes himself as “on the real nonfiction end of nonfiction.”

He suggests the question could be a good subject for one of the panels of alumni writers he regularly runs at Writers House over Homecoming Weekends. “To talk about the underpinnings of some of the set pieces in our books, to see how much reporting that we needed to take it the rest of the way,” he says. “Certainly, readers are happy that it’s very narrative. The question is, is it authoritative, also?”

More generally, Fried just seems to like the fact that he can tackle a range of subjects, even if a narrower focus might result in greater name recognition—the Stephen Fried brand. “If I only wrote about one thing, maybe more people would know exactly what it means to read a book of mine,” he speculates. On the other hand, “I always thought it was cool—and this comes from writing for magazines—the idea that somebody would go, ‘What is he learning about now? I like the way he writes. I like his take on things. I’ll go there with him.’ The nonfiction writers that I loved were the ones who did that.”

For now, Fried says, he’s working on two book proposals, one “for a book that is similar in format to this one, and one that isn’t. And we’ll see what happens.”

EXCERPT

From the wiving of the West to the depths of the Depression, the fate of the Fred Harvey company was intertwined with the nation’s history, as these scenes from Stephen Fried’s new book, Appetite for America, demonstrate.

—J.P.

“Those Roughnecks Learned Manners!”

One day Fred received a wire from his manager in Lamy, New Mexico, requesting help after a “gang of gamblers and confidence men” had taken over the town and robbed all the Santa Fe employees. Actually, the thugs were now ordering all their meals at the Santa Fe eating house and then refusing to pay. When the manager finally got up the nerve to tell the men he wouldn’t serve them anymore, they pulled their guns and told him to get out of town.

Fred arrived in Lamy on the next train, accompanied by his scariest-looking employee, a hulking cashier named John Stein. They were sitting in the restaurant the following morning when a dozen desperadoes entered, demanding to eat. When refused service, they asked for the manager.

Fred approached them. “What do you want with the manager?” he asked.

“We want to hang him,” they said.

“Well, I hope you won’t do that, because he’s a good manager and I need him to run the place. However … I don’t need him,” he said, turning his gaze to the massive Stein, “and you can hang him as often as you like. But as long as he’s alive, you pay for your food or you don’t stay.”

Big John Stein stared at the men, unblinking, until they tossed some money on a table and left. Then he and Fred had breakfast and waited for the eastbound train.

By this point, Fred was no longer surprised by the holdups; a certain number of Santa Fe trains and depots were always going to be robbed, it was just the cost of doing business. But what he could not abide were the continuing racial problems he saw at his new eating houses.

Western restaurants commonly hired black men as waiters and busboys. But many cowboys were former Confederate soldiers who had fled the South because they could not imagine living in peace among freed slaves. The cowboys’ prejudice against black workers was often more extreme than any tensions they had with Indians—whom they at least feared, and sometimes grudgingly respected.

The truth was that Fred Harvey’s black male waiters got little respect and often lived in fear. They had every reason to believe that, at any time, they might need to defend themselves against their own customers.

In the early spring of 1883, Fred received word of a drunken fight among the beleaguered all-black waitstaff at his eating house in Raton. The manager reportedly told Fred there had been a midnight brawl and “several darkies had been carved beyond all usefulness.” There was also a more elaborate version of the story circulating, in which the intoxicated waiters had not only fought each other with knives and guns but accidentally shot and killed a Mojave spectator. Tribal leaders were supposedly demanding the life of a waiter in return. When told the shooting was accidental, the Indians declared they “would be satisfied to shoot one of the Harvey waiters by accident.”

Fred jumped on the next train to Raton. He was traveling with young Tom Gable, a family friend from Leavenworth, Kansas, whom he had watched grow up. Fred had known Tom as smart and able from the time he started working in the Leavenworth post office as a teenager. Now 31, with a wife and a baby, Tom had let Fred know he had ambitions of finally leaving Leavenworth, and hoped there might be a place for him in the eating house business.

In Raton, Tom watched in fascination as “old Fred lit like a bomb,” instantly firing the manager and the waitstaff. As Tom would later recall it, Fred then turned to him and said he should become the new manager in Raton and move his young family there.

“I had no restaurant experience,” Tom said, “but one did not argue with Fred Harvey.”

The two of them talked about how the situation in Raton might be improved, and Tom insisted he would take the job only if Fred would let him try something completely different. He wanted to replace all the black male waiters with women—but not local women. He wanted to import young white single women from Kansas. He thought they would be easier to manage, less likely to “get likkered up and go on tears.”

It was a radical idea. Still, one of the things Fred relished most about management was acting on the brainstorms of his employees. He had always hired some female servers for less hostile locations—his houses for the Kansas Pacific had a few waitresses, and so did the original Santa Fe eating houses, starting with The Clifton Hotel in Florence. One of the original waitresses there had been Matilda Legere, a 16-year-old from Belgium, who never forgot the first thing Fred Harvey ever said to her: “Don’t throw the dishes so hard or you’ll break them.” In fact, as early as 1880, when Lakin, Kansas, was still the “far West” for the Santa Fe, there were young women on the waitstaff, including Fred’s niece, Florence.

Still, while female servers may have worked in Kansas, it was considered far too dangerous to have single women waiting on tables in forward positions in New Mexico. There were, according to the old joke, “no ladies west of Dodge City and no women west of Albuquerque.” But that was exactly why Tom Gable believed Fred should try it. He thought the move could have a positive, calming influence, first and foremost on the men working at the eating house and the train depot but also, perhaps, on the customers as well. The women could help alleviate racial tensions, and maybe even make the cowboys a little more gentlemanly.

They would also be a welcome addition to the community, because the West was desperate for women. Recent stories in the Omaha Bee and the Laramie Boomerang had bemoaned “The Scarcity of Women Out West,” citing data from the recently tallied U.S. census. Overall, there were one million more men than women in the United States. While the eastern states had “large excesses of females,” the farther west one traveled, the more the numbers painted a man’s world, and a lonely man’s world at that. Some of the western states had a two-to-one “surplus of males.”

Fred agreed to let Tom Gable try his idea. They sent cables back to Kansas—where Sally, Tom’s mother, Mary, and his wife, Clara, and Dave Benjamin and his wife, Julia, started reaching out to local single women who might agree to be trained by Fred Harvey for a good paying job.

“And that,” Gable later explained, “is how I brought civilization to New Mexico. Those waitresses were the first respectable women the cowboys and miners had ever seen—that is, outside of their own wives and mothers. Those roughnecks learned manners!”

The Ritz of the Divine Abyss

Building a new luxury hotel at the Grand Canyon, some 60 miles from a dependable source of fresh water, was, predictably, a nightmare. The new hotel finally had a name: El Tovar, after Don Pedro de Tovar, the Spanish conquistador who first told his boss, explorer Francisco Vásquez de Coronado, about this natural wonder, leading to its “discovery” by white men in 1540.

Construction on the building immediately fell way behind schedule, and Ford Harvey [Fred’s son, who ran the company following his death in 1901] was getting nervous. He was accustomed to delays—after all, he worked with the trains, so his life was all about delays and feeding people who were famished and cranky because of them. But the El Tovar delays were different. This was not another trackside hostelry in the middle of the desert or the prairie. This was the Ritz of the Divine Abyss, a monument to the new American pastime of “sightseeing” and a project whose progress the president of the United States, and the entire nation, were watching.

In the late fall of 1904, Ford went back to the Grand Canyon to oversee the end of construction at the South Rim. He slept in one of the rustic rooms at the old Bright Angel next door, which now looked like a run-down carriage house for his new hotel complex.

Regardless of the myriad delays and budget overruns, Ford was pleased with El Tovar. It was the ultimate Fred Harvey oasis, in every way honoring President Roosevelt’s plea not to deface the canyon. It was an intriguing combination of styles and materials, a cross between a log cabin castle and a Swiss chateau, its dark wood floors, walls, and ceilings decorated with an occasional Indian rug or moose head. The long, narrow building had 125 guest rooms, and a massive square-helmeted turret rose above its three-story center staircase—an architectural feature that served to hide the water tower inside the roof, which would be filled several times a week with water carried to the canyon by railroad car. But its architecture, ultimately, was less impressive and surprising than the simple fact of its location—it was hard to believe that a luxury hotel could be built so far from civilization, and so close to the edge of the Divine Abyss.

Just across the circular driveway from El Tovar was a similarly counterintuitive structure. It was a replica of an actual Indian building—a full-scale, brand-new, 800-year-old pueblo, authentic to the smallest detail, where the Indians who were hired to do art demonstrations and dances would actually live. Inspired by buildings in the nearby reservation city of Oraibi, it was called Hopi House.

The cost of the two new buildings—trumpeted in the promotional materials because it was higher than the price of the Union Pacific’s Yellowstone hotel—was $250,000 (the equivalent of $6.3 million today). Another $50,000 ($1.3 million) was invested in stables for the horses that guests would ride along the rim and the mules on which they would descend into the canyon. While the railroad owned the buildings, Fred Harvey was responsible for buying, training, and maintaining the livestock, as well as running the on-site farms where fruits and vegetables were grown for the restaurant.

But El Tovar and Hopi House, while extraordinary, were not the main selling points. The first Santa Fe ads, which started running across the country well before the opening, promised nothing less than the chance “to see how the world was made … deep down in the earth a mile and more you go, past strata of every known geologic age. And all glorified by a rainbow beauty of color.”

El Tovar made its debut on January 14,1905—a soft opening in the dead of winter when the canyon often got an abundance of snow, so there would be plenty of time to work out the kinks before the anticipated throngs of summer.

The large Fred Harvey staff immediately doubled the number of people living along the canyon. The influx of Harvey Girls was especially welcome. They represented more single women than had ever been seen in northern Arizona, and the tour guides and miners particularly enjoyed their regular Friday night socials, chaperoned by the large and formidable Miss Bogle, the housemother of the Harvey Girl dormitory. Miss Bogle always kept her eye on the Kolb brothers—Emery, Ellsworth, and Ernest—a randy trio who ran the local photography studio but were best known for their off-camera exploits with the ladies, which they referred to as “rimming,” their code word for finding a secluded place along the canyon edge to make out. When Ernest Kolb danced too wildly and too close to a Harvey Girl, Miss Bogle would simply walk over, lift him up, look him in the eye, and say, “Stop your jiggling, you hear?”

As the inaugural summer tourist season arrived, the first newspaper reviews were ecstatic. The Los Angeles Times called the hotel “magnificent”:

Reared upon the very brink of the dizzy gulf of the gorge, the view afforded the guests from its windows and balconies is something to live long uneffaced in the memory … To live in El Tovar is like enjoying the sensation of occupying a room in the top floor of a hotel more than 400 stories high, or in the pinnacle of seven Eiffel Towers piled one on top of the other, but fortunately without the inconvenience of having to send to China for a bell boy every time one rings for water.

“These People Are the Guests of Mr. Fred Harvey”

As the Depression deepened, the Harvey Houses became known as the softest touches in the West, the places where impoverished locals and drifters went in search of a free meal. It was company policy never to let anyone who couldn’t afford to pay leave hungry. Many begged for food at the back door and were pleasantly surprised to get sandwiches, fruit, bread, and coffee. Others came in through the front door.

Bob O’Sullivan, who later became a well-known travel writer, never forgot the hot, dusty fall afternoon in Albuquerque when he was a second grader and his family had to rely on the kindness of strangers in Harvey Girl uniforms. His mother was driving him and his 11-year-old sister—with all their belongings—to California, where they hoped to meet their father and make a new start. The O’Sullivans had arrived in Albuquerque expecting that $25—several weeks’ pay—had been wired to them at the Railway Express office. But when his mother walked out of the office in tears, Bob knew the money hadn’t arrived. As she pulled on her driving gloves, the children asked if they could still get something to eat.

She hesitated.

“Of course we can,” she said finally. “We have to, don’t we?”

She drove along the railroad tracks to the Alvarado and led her children into the dining room. There were few customers there, but lots of delicious aromas, and every surface was gleaming. When a smiling Harvey Girl approached them, her puffed sleeves and starched apron rustling, Bob’s mother pulled her aside and whispered something. The waitress walked to the kitchen and returned with a man wearing a suit, to whom his mother also whispered. Then they were led to a table, where Mrs. O’Sullivan began to order sandwiches for the kids and just a cup of coffee for herself—until the man in the suit interrupted her.

“Why don’t you let me order for you?” he said, and proceeded to tell the Harvey Girl to bring hot soup, then the beef stew, mashed potatoes, bread and butter, and coffee for the lady. He asked the children if they wanted milk or hot chocolate.

“Yes, sir,” they both said.

“Milk and hot chocolate for the children,” he continued, “and some of the cobbler all around. Does that sound all right?”

“Will that be all?’ the waitress asked.

“Oh,” the man said, “and these people are the guests of Mr. Fred Harvey.”

Bob saw his mother mouth the words “Thank you.”

The taste of that stew would stay with him his entire life. As would the memory of what happened when they finished eating. His mother pushed what few coins she had left toward the waitress, who pushed them back with a smile.

“Oh, no, ma’am. You’re Mr. Harvey’s guests,” she said, placing two bags in front of them. “And the manager said I was to wrap up what you didn’t eat, so you could take it along.”

“But we cleaned our plates,” young Bob blurted out. His sister sighed and looked at him as if he were the dumbest person in the world. Then the Harvey Girl started giggling, followed by his mother and then the kids.

In the car, Mrs. O’Sullivan opened the bags, and found them filled with more food than they had eaten for dinner.

“What’s in them?” Bob asked.

“Loaves and fishes,” she replied, shaking her head in amazement. “Loaves and fishes.”

EXCERPT: From the book, Appetite for America, by Stephen Fried. Copyright © 2010 by Stephen Marc Fried. Published by arrangement with Bantam Books, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc.