Street Vendor Project Director Sean Basinski can tell you all about the mouth-watering offerings available from New York’s food trucks and carts—and even more about the daily struggles faced by the immigrant men and women who operate them.

By Jordana Horn | Photography by Candace diCarlo

When Sean Basinski W’94 started college, like all good Lower Quad residents he frequented the Le Anh food truck. His regular order: pepper steak, $2.50.

Basinski hailed from Vienna, Virginia, where, he says, the culinary options were somewhat limited. “There was one Chinese place there, and that was pretty exciting—and one Mexican place which I didn’t like, because I was afraid of Mexican food,” he recalls. “I didn’t know what falafel was. [At Penn] there were all those trucks lined up, and I never really went to those places.”

But while Basinski may not have wandered far in his dining choices on campus, in crossing Spruce Street to get his pepper steak the freshman was taking the first steps toward a pretty much uncharted professional future—and one revolving around food trucks. After graduating from Penn he overcame his childhood fears sufficiently to operate a Mexican-food cart in midtown Manhattan for several months before starting law school at Georgetown University. But his main focus for much of the past decade has been on protecting the rights and interests of immigrants working to sell food and wares on the streets of New York as the lawyer and community activist at the head of the Street Vendor Project—efforts which led New York magazine to dub him “the Cesar Chavez of hot-dog stands.”

Basinski dismisses the Chavez parallel with a laugh. “That’s over the top,” he says. “If my story can capture people’s attention, that’s fine. My job is just to try to understand that, and to take their attention off of me and [focus it] onto the community of people that’s out there.”

Basinski started the Street Vendor Project (www.streetvendor.org) eight years ago. It teaches vendors about their legal rights and responsibilities, publishes reports to raise public awareness, and links vendors with small-business training and loans. The project has nearly 1,000 members—impressive, but only about a tenth of the 10,000 or so vendors selling everything from flowers to fruit to cartoons on New York’s streets.

“There’s an overarching issue of a lack of organization and representation, and that is what we’re trying to change,” Basinski says. “We have to be a lot stronger.”

Much of Basinski’s work involves creating more opportunities for vendors to get started, advocating to reduce fines and harassment, and cutting through bureaucratic obstacles that can crush these vulnerable, low-margin businesses.

The number of merchandise permits available in the city is very limited, Basinski says; his group lobbies for more, as well as for opening more streets to vendors. “It’s part of a political calculus,” he explains. “Over the years, businesses have been very effective in closing many—usually the best—streets to vending. We want to reopen those streets to create other areas where vendors can legally vend.”

Vendors who do manage to get permits to operate face a labyrinth of regulations: They cannot be within 10 feet of a crosswalk, for example, or 20 feet of a building entrance. They may not vend more than 18 inches away from the curb. Before 2006, the maximum penalty for infractions of any of these regulations was $250. Under Mayor Michael Bloomberg, the maximum was hiked up to $1000.

“One hundred dollars would be a great day’s work for most vendors,” Basinski notes with some heat. “This is obviously just a case of economic injustice that goes after the smallest of small businesses—and does so at a rate that is far more [as a percentage of revenues] than any big business would ever have to pay.” Similarly, it takes a month to replace a lost or stolen vendor license—a month’s wages lost due to bureaucracy, indifference, bigotry, or a combination thereof.

And the city can treat vendors this way with impunity, Basinski adds, if there is no one to speak up on their behalf. Most of the city’s vendors are Bangladeshi, Chinese, Senegalese, or Egyptian, he estimates—none of whom are equipped with either English as a first language or a sense of their rights under the law.

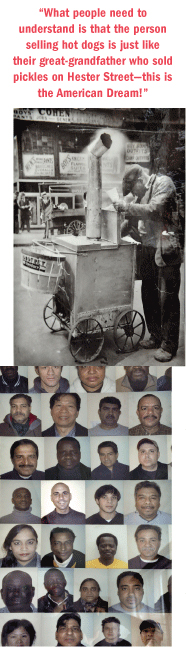

But such diversity does make for some lively exchanges. The group’s monthly meetings, Basinski says, are “a trip” as a result. “We’ve got all different languages going. It’s a little hectic sometimes, but it’s a beautiful representation of the immigrant experience,” he explains. “What people need to understand is that the person selling hot dogs is just like their great-grandfather who sold pickles on Hester Street—this is the American Dream!”

New York’s Tenement Museum takes in millions in annual donations, for example, Basinski adds, “but there’s a real life immigrant history! Now! And that should be valued as much. These are the people who are powering our city every day. It’s not just a matter of going to a museum. Look around you!”

On a Tuesday afternoon in January, Basinski weaves his way down the sidewalk outside his office near Wall Street. We are taking a lunch break from my shadowing him as he works in the Urban Justice Center (where the Street Vendor Project is one of several initiatives aiding poor and vulnerable populations in the city). This is the financial district, so Basinski is far from the only Wharton graduate in the vicinity. So far as I can tell, though, he is the only one being greeted with hugs and smiles from the Eritrean vendor selling goat curry; the Bangladeshi nut seller; or the Peruvian woman hawking gloves, hats, and scarves. Whatever their first languages or homelands, each of these immigrants conveys genuine affection and gratitude.

Basinski could easily have been one of the guys in the suits walking fast on the street, instead of the guy climbing up into the food truck to say hi to Kiflu and Nazim. His choice has roots in his own history. After he graduated from Penn in 1994, Basinski had a job offer to work for two years in a junk-bond analyst program. It didn’t take, and he left the day the two years were up.

He then proceeded to sate his twenty-something sense of wanderlust, traveling around Europe and northern and western Africa. He returned to New York to be with a woman he was dating, and with some time on his hands. He’d been accepted to Georgetown’s Law School for the following fall, but didn’t want to spend the time before school started—nine months and change—working for a law firm or an investment bank.

By now he was well past his earlier aversion to unfamiliar cuisine. While traveling in Africa, he had spent a lot of time eating street food. At some point, he recalls, he had been mulling over the idea that Californians often complained that there was “no good Mexican food in New York.” He’s not sure exactly when or why, but somewhere along the way he decided to use the months before law school to prove them wrong by opening his own Mexican food cart, changing his life in the process.

He found that getting a license to sell food wasn’t particularly difficult, even though he had had no prior experience. He negotiated with a vendor he met on the street to rent the vendor’s permit for a few months over the summer. Knowing nothing about food carts, he went to Chinatown and hired someone to build him a cart out of sheet metal. At night, he left the cart in a storage facility near his apartment.

Basinski found a good spot to vend on 52nd Street and Park Avenue, only a few blocks from his home at 59th and First. He admits that he “cut a lot of corners,” not knowing the ways of the business and having no guidance. He made the food in his apartment every morning—which, as it happens, is prohibited by the city’s health code—and pushed the cart to work.

“It got kind of lonely, and it was very physical,” Basinski says. “I live on the fourth floor of a walkup, so I’d pull the cart upstairs, run and grab the rice, run downstairs, run up and grab the chicken, run downstairs … It was too much. I remember scrubbing the pan in my bathtub on a summer night. It was hot, and I’d be in the street all day, then push this thing back at four in the afternoon and start cleaning and preparing for the next day.”

He learned that food service is “grueling—especially if you’re doing it all by yourself in your apartment.” The compensation fell a little short of investment banking, too. “The best day ever, I sold 81 burritos—that was far and away the best day,” Basinski says. “They were about five dollars each, so $400 was the best-case scenario. Half of that was costs! So on the best day, I’d make maybe $200.”

Basinski laughs when I press him on his earnings. “I tell people I didn’t really keep very good records, but I like to believe that after the summer I broke even on all my expenses, including making the cart and everything,” he says. “That’s probably an optimistic spin on things. Or maybe I broke even … if I considered that I didn’t pay myself a salary.”

It was still a collared job, even if not white collar: Basinski had polo shirts with a logo made to set him apart from the competition. “That was my whole shtick,” he laughs. “I was trying to brand it in a way that was different—capitalizing on the bad image that vendors had, and still do have, of these dirty, sweaty men selling dirty food from dirty carts.”

He found that, as a well-spoken and educated white man, his life was easier than that of his vending peers, immigrants from all over the world. “It would have been interesting to have seen how the police or the health department would have treated me: I would have asked for their names and badge numbers!”

The difference between his comparatively pleasant experience vending and those of the vendors around him was striking. “Vendors are treated like garbage all the time because they’re scared—they don’t understand the language very well, and they don’t have the capital to fight back the way you or I would,” Basinski says. “They don’t know that they shouldn’t accept that kind of treatment.”

Despite the disparity in their backgrounds, his fellow vendors immediately made him feel welcome. “You get change from each other, or you give each other food as a courtesy, or you watch other vendors’ carts when they have to go to the bathroom,” Basinski explains. “I just felt like I was accepted and embraced by the community.”

Working on the street gave him a window into a way of life he’d previously never even noticed, much less thought about. It also sparked what he characterizes as his “political awakening” when then-mayor Rudy Giuliani made a push to close down many streets to vendors.

“Someone handed me a flyer about it, and soon I was passing out flyers and marching down Broadway in support of street vendors,” Basinski recalls. “We stopped most of the street closings. That was when things were starting to change, and people were realizing Giuliani’s power was a function of him picking on little people.”

Basinski went on to Georgetown Law with the idea of working in the public sector. He was awarded a fellowship from Yale to do legal work on behalf of street vendors. Although it wasn’t a lot of money, it was a turning point, Basinski says. “When I got that [fellowship], I gained a lot of confidence: I could do this, and I could work with street vendors in some way. I thought, maybe I’d do it from my apartment—I didn’t know, but I felt sure that I could make it work. I didn’t care if I’d have to wait tables at night to do it—if at least one person thought it was a good idea, then other people would agree.”

By the summer of 2001, Basinski had graduated from Georgetown and was still in Washington, waiting to return to New York. As of September 11, he was waiting to hear about a grant application pending with the New York Foundation for his work. In a strange way, the tragic events of that day actually had a positive effect in terms of support for his work.

“It was clear that this was going to be a really big issue for street vendors—immigrants, Muslims, you name it,” Basinski says. “Even after the streets were opened up again in lower Manhattan and people were allowed to return, the vendors were being stopped at Canal Street and told that they couldn’t go back to work.” The New York Foundation sped up his grant, and the Urban Justice Center, headed by fellow Penn graduate Doug Lasdon W’77, offered to provide a home-base for his work.

Basinski took to the streets, walking around downtown and talking to vendors. While he did a lot of work with more conventional relief programs like the Red Cross and Safe Horizons, he found that vendors were not covered under their efforts: “There were programs for residents, but vendors don’t live down there, and programs for small businesses, but vendors didn’t count as small businesses because they didn’t have leases.”

Basinski and his work have become well enough known that he has begun to take his efforts beyond New York. He has recently traveled to Nicaragua and Los Angeles for conferences on street vending, for example, and he spent the first half of 2009 on a Fulbright fellowship to study street food and street vending in the economy of Lagos, Nigeria, walking the streets and talking to vendors just as he would on the streets of New York. Basinski prepared a report on his findings for the CLEEN Foundation, the Nigerian non-governmental organizations that hosted him, and presented them at a talk and panel discussion at the U.S. Consulate in Lagos in July before heading back to New York. (Basinski’s blog about his trip is available at seaninnigeria.blogspot.com).

He found similarities in the adversarial relationship between the police and vendors in New York and Lagos, with “a lot of the same trends and power dynamics” operating in both places—only more so in Lagos, where “government officials are engaging in crackdowns, arrests, and confiscations of goods on a massive scale,” he says.

“Lagos is a very special place for lots of reasons—how chaotic it is and how challenging it is, but how vibrant its informal economy is.” Basinski estimates the number of vendors—called hawkers and street traders—in Lagos as being in the hundreds of thousands.

“Even the greatest problems, no matter how great they are in New York, in Lagos, they are much, much worse,” Basinski says, citing the total apathy of the Nigerian government toward the rights of hawkers.

“It’s relatively easier to make a difference on an international scale when you’re doing social justice work, if only because there are so many more injustices—no one is doing the work at all,” he adds. “No one had even thought that these vendors were providing an important service as a critical part of the economy. When the pendulum has swung so far the other way, then you can bring it back a little bit.”

Upon his return to New York, Basinski threw himself into preparations for the Vendys—an annual competition that confers bragging rights to winning food vendors in several categories and, more practically, serves as the main publicity and fundraising vehicle for the Street Vendor Project’s shoestring operation. Basinski launched the event five years ago, and it has attracted lots of attention from both the media and the “foodie” community—even being described as the “Oscars of food for the real New York” by celebrity chef Mario Batali, according to The New York Times.

Held outside the Queens Museum of Art in Flushing Meadows (location of the 1939 and 1964 world’s fairs), this year’s event in late September attracted close to 1,000 people, who paid $80 in advance or $100 “at the door” ($150 for table service). Special donor packages featuring “lots of extras” were also available for between $200 and $1,000, plus an auction with prizes that included lunch with humorist and food-writer Calvin Trillin and cooking lessons from the editors of Saveur magazine.

The finalists for the Vendy Cup and other awards for best dessert and “rookie-of-the-year” parked their trucks under the famous World’s Fair Unisphere, offering patrons a smorgasbord of delights ranging from Elvis cupcakes (bacon and peanut butter!) to dumplings. Everyone was proud of their wares—and everyone desperately wanted the Street Vendor Project to get more press, more funding, and more success.

Fares Zeidaies, the self-styled “King of Falafel and Shawarma,” talked to me in between serving the never-ending line of customers. He’s spent seven years vending his wares at 30th Street and Broadway in Astoria, Queens, and he was clearly thrilled to be a Vendy finalist—no one’s smile was bigger. “Hey, I’m killing myself here, but I’m happy,” he said as he squirted tahini on someone’s platter. “This makes people appreciate food vendors. And when the city keeps pushing us around, we need all the help we can get.”

Doug Quint, proprietor of The Big Gay Ice Cream Truck, a top dessert contender, agreed. “These people need all the help they can get,” he said, gesturing to the carts around him. “They work 12-hour shifts, standing the whole time, for not much pay. They have the ability to work legally, but without the Street Vendor Project, they have none of the defenses that those of us who are native-born have.”

(For the record, the 2009 Vendy Cup was awarded to the Country Boys taco truck, which operates only on weekends at the soccer fields in Red Hook, Brooklyn; the Austrian-themed Schnitzel & Things took the newcomer award; and dessert honors went to Wafels & Dinges. The People’s Taste Award was won by Biryani Cart. Videos and lots of other information can be accessed from www.streetvendor.org/vendys.)

Basinski seems a bit ambivalent about the hoopla surrounding the Vendys, which this year included a segment on the CBS Early Show, in which “resident chef” Bobby Flay visited some of the finalists, sampling their wares; stories in the Times and the U.K.’s Guardian newspaper, The Huffington Post, and elsewhere; plus bite-by-bite-coverage in blogs like Midtown Lunch and Serious Eats. The increase in “foodie culture” has been helpful, but it’s only the beginning, he says, noting that he doesn’t want the Vendy Awards to eclipse everything else the Street Vendor Project is trying to accomplish.

“I think the community of people who really care about social justice in New York City is relatively small—that is, the people who really follow these things and care about the plight of struggling immigrants,” Basinski adds. “The community of people who follow food is huge and growing, and people are so tapped in that it’s definitely helped us to broaden our appeal: to take some of these people and educate them about the issues so that they can be our allies.

“Maybe they’re mostly interested in how the food tastes, and not the plight of the workers … but the plight of the worker can come with the flavor of the taco or whatever they’re interested in,” he says. “I know not everybody is going to care, but maybe some of them will—and hey, even if they only care about vendors because it’s going to affect their lunch or eating options … I guess that’s better than nothing.”

Jordana Horn C’95 L’99 is a frequent contributor to the Gazette.