He’s now remembered, if at all, for a misguided “rest cure” that inspired an iconic piece of early feminist fiction, but in his day alumnus and longtime University trustee S. Weir Mitchell found fame in several fields—as a noted surgeon and physician, a leading medical researcher, and a best-selling author.

By Dennis Drabelle

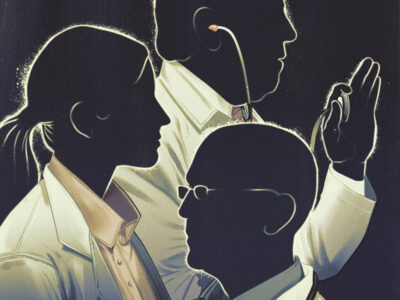

Portrait of S. Weir Mitchell (1829-1914) by John McClure Hamilton

(1853-1936). Oil on canvas, 1902. University of Pennsylvania Art Collection.

Nineteenth-century America played host to a renaissance of the Renaissance Man. In a rapidly expanding economy fueled by vast territorial acquisitions and dramatic technological breakthroughs, not only could a smart, ambitious white male become just about anything he wanted to, he could do it more than once. Take Frederick Law Olmsted, who designed Central Park, ran the US Sanitary Commission (a precursor to the Red Cross) during the Civil War, and afterward reshaped dozens of American cities as a landscape architect. Or Samuel F.B. Morse, who won fame as both a painter and the inventor of the telegraph.

Penn contributed its share of these polymaths to the nation. An 1853 graduate of the medical school, Isaac Israel Hayes, explored the Far North, directed a large hospital, and won election to the New York State Assembly [“Pointing the Way to the Pole,” Nov|Dec 2011]. Another physician, S. Weir Mitchell (1829-1914)—who attended Penn without graduating but later became a fixture at the University—was a giant of modern medicine, an accomplished scientist of wide-ranging interests, and a novelist mentioned in the same breath as Nathaniel Hawthorne. Time has not been kind to the imaginative doctor, however. His medicine has been superseded, his books have gone out of print, and he is in danger of being remembered mainly as a bogeyman to one of his patients. Yet his best novel is so good that it ought to rescue its author from oblivion.

S. Weir Mitchell—his first name was Silas, but he seems not to have used it—came from a clan of doctors, including his father, John Kearsley Mitchell, who practiced in Philadelphia and taught at Jefferson Medical College. The Philadelphia in which the boy grew up was so inchoate, he recalled, that “beyond Sixteenth Street no house broke the long road to the Schuylkill.” Closer to the Delaware, the American Revolution was still a living presence; the young Mitchell knew men who as boys had seen British General William Howe and his soldiers in the city streets.

On entering Penn at the age of 15 in 1844, Mitchell demonstrated his callowness by writing too much poetry and playing too many games of billiards instead of hitting the books. When his father fell ill, the boy took the opportunity to drop out, pitch in at home, and grow up some. In 1848 he resumed his education, not at Penn but at Jefferson, from which he received a medical degree in 1850. After a year of post-graduate study in Paris, he returned to Philadelphia, where he joined his father’s practice.

When the senior Dr. Mitchell died in 1858, the son took over. That same year he married Mary Middleton Elwyn, with whom he had two sons before her death from diphtheria in 1862. In 1874 he took a second wife, Mary Cadwalader, whose family connections gave him entree to Philadelphia’s aristocracy; a third child, a daughter, was born in 1876.

During the Civil War, Mitchell did his part as a contract surgeon (one who treated wounded men on an as-needed basis) at Turner’s Lane Hospital in Philadelphia. His work there provided material for his first two nonfiction books, both published in 1864: Gunshot Wounds and Other Injuries of Nerves and Reflex Paralysis.

From the outset of his career, Mitchell had considered himself as much a scientist as a sawbones. While continuing to write poetry, he spent a lot of his spare time peering into microscopes. He parlayed this work, along with the experiments he performed and the observations he recorded as a practicing physician, into well over a hundred published papers and books, on subjects including “the generation of uric acid,” the properties of snake venom, “Blood Crystals of the Sturgeon,” the physiology of the cerebellum, and the buttons of the mescal plant (after ingesting some of the latter, Mitchell dutifully noted their trippy effects). His achievements were recognized as early as 1853, when he was elected a member of the Academy of Natural Sciences. Ultimately, however, he concentrated on a single field, albeit a broad one: neurology and nervous disorders, about which he published both scholarly tomes and such popular treatments as Wear and Tear, or Hints for the Overworked.

Whatever the subject, Mitchell wrote about it with lucidity and grace, as witness this evocation of a phenomenon he observed as a Civil War surgeon: “Nearly every man who loses a limb carries about with him a constant or inconstant phantom of the missing member, a sensory ghost of that much of himself, and sometimes a most inconvenient presence, faintly felt at times, but ready to be called up to his perception by a blow, a touch, or a change of wind.”

Lost limbs figured prominently in Mitchell’s 1866 debut as a fiction writer, the whirlwind nature of which he recounted much later: “‘The Case of George Dedlow’ was not written with any intention that it should appear in print. I lent the manuscript to the Rev. Dr. Furness and forgot it. This gentleman sent it to the Rev. Edward Everett Hale. He, presuming, I fancy, that every one desired to appear in the ‘Atlantic,’ offered it to that journal. To my surprise, soon afterwards I received a proof and a check. The story was inserted as a leading article without my name.” How easily things could fall into place in the 19th century for one who knew the right people!

(Download a PDF of “The Case of George Dedlow”)

Not that the story was undeserving. Narrated in the first person by Dedlow, it’s the gripping tale of a Union Army doctor who gets wounded on multiple occasions. On display is the author’s ability to describe both the sensation of pain and the psychology of the one feeling it. After being shot in the right arm by Confederates, Dedlow experiences numbness, followed by “a strange burning, which was rather a relief to me. It increased as the sun rose and the day grew warm, until I felt as if the hand was caught and pinched in a red-hot vise.” Dedlow’s agony persists for six long weeks, until he is ready to welcome a procedure he had once abhorred—amputation. When he wakes up and notices his severed arm lying nearby, he reacts with equanimity. “There is the pain, and here am I. How queer!”

Alas, this will not be the poor fellow’s only amputation. After Dedlow sees more action and takes another bullet, Mitchell evokes with brilliant economy the experience of being anesthetized for battlefield surgery. “A steward put a towel over my mouth, and I smelled the familiar odor of chloroform … In a moment the trees began to move around from left to right, faster and faster, then a universal grayness came before me—and I recall nothing further until I awoke to consciousness in a hospital-tent.”

Even with a supernatural twist at the end—with the aid of a medium, Dedlow makes contact with his amputated legs in the spirit world, and is briefly “reindividualized, so to speak,” walking across the room on invisible limbs before being left “resting feebly on my two stumps upon the floor” and fainting—the story was so convincing that some Atlanticreaders took up collections for Dedlow. (Read the story at our website, www.upenn.edu/gazette.)

In his first try at fiction, Mitchell had achieved something fresh: a realistic and informed depiction of a medical predicament. Almost two decades would go by before he wrote his first novel, however, and even then he wasn’t satisfying any great itch to make a mark. A friend recalled Mitchell telling an audience at Vassar College that he wrote novels “because having read all there were to be had, he desired more.” On another occasion, he dismissed his literary pursuits as unimportant compared to his medical work. He also kept the two endeavors separate, writing his novels during summer vacations in Maine.

And yet that first novel, In War Time (1884), can almost be considered an extension of the medical work. Its protagonist, Ezra Wendell, is a contract surgeon with the Union Army. He differs from his creator, however, in being a weakling whose medical carelessness causes the death of a friend. In a novel that could do with a tighter structure, the omniscient narrator makes a comment about Wendell’s sister which probably reflects the author’s own views. “Being a woman, and therefore automatically sacrificial, she could not estimate the immense proportion of energy she thrust, somehow, into his daily life.”

Mitchell was well into middle age when In War Time came out. His friend and fellow-novelist Owen Wister—whose The Virginian introduced many tropes of the Western genre but who grew up and was buried in Philadelphia—left a portrait of him at that stage of life. “As I was crossing Sixth Street at Chestnut, an approaching figure arrested my attention. He was about half a square away, opposite the door of Independence Hall. He was a lean man with a lean face, and seemed tall, vigorous, alert, and gray. His rough cap was gray, too, and gray the longish cape that hung from his shoulders; and distinction beaconed from his whole appearance.” A moment later, Wister realized who this prepossessing fellow was.

Oddly, neither of the caped physician’s alma maters—Penn and Jefferson—saw fit to hire him as an instructor. (Penn did make him a trustee of the University in 1875, a position he occupied for 35 years.) But on the strength of his practice, his writings, his bedside manner, and his connections, Mitchell was held in awe as perhaps only a famous doctor can be. After his death, the president of the National Academy of Sciences went so far as to call him “the foremost figure in American medicine.”

Mitchell’s reputation had even reached overseas. Once, while visiting Paris, he fell ill and consulted the great neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot. Charcot didn’t catch the patient’s name but ascertained that he was from Philadelphia. “You should consult Weir Mitchell,” the Frenchman advised. “He is the best man in America for your kind of trouble.”

Mitchell’s foremost contribution to the medicine of his time was the rest cure. This was much stricter than the amorphous R&R to which we might give that name today—and far removed from the socially interactive convalescence available at, say, the tuberculosis sanatorium of Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain. Prescribed almost exclusively for overwrought women, Mitchell’s method called for near-total indolence, with the patient keeping to her room, where she was waited on, given massages, and warned against doing much of anything for herself. Many women were willing to give this a try, not least because of Mitchell’s “personal charisma,” noted physician Diana Martin, in “The Rest Cure Revisited,” from the May 2007 American Journal of Psychiatry. “The quantity of mail he received from his adoring female patients attests to the fact that he was ‘electric with fascination.’”

At least one female patient, however, came to resent that electricity and what it put her through. In the spring of 1887, she agreed to place herself in Mitchell’s care, abiding by a regimen that she summarized as: “Live as domestic a life as possible. Have your child with you all the time … Lie down an hour after each meal. Have but two hours’ intellectual life a day. And never touch pen, brush or pencil as long as you live.” While following these rules, she recalled, she “came perilously close to losing my mind.”

Her name was Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Descended from a brainy New England family that counted Harriet Beecher Stowe among its stars, Gilman eventually distinguished herself as a feminist, a public intellectual, and the author of Women and Economics. How temperamentally ill-suited she was to extreme rest can be gauged by her astonishing performance two decades after her brush with Mitchell. Between November of 1909 and December of 1916, she wrote the entirety of her own monthly magazine, The Forerunner. At 32 pages per issue, the magazine’s seven-year run added up to the equivalent of 28 full-length books!

In hindsight, it’s not difficult to see what ailed Gilman in 1887. She was in an unhappy marriage and suffering from depression exacerbated by the roadblocks placed in the way of bright, industrious women like herself. What she undoubtedly needed was liberation, not confinement. At any rate, the memory of her medically sanctioned imprisonment rankled until 1892, when she struck back by writing what has become both a much-anthologized ghost story and a canonical text of the American feminist movement: “The Yellow Wallpaper.”

It takes the form of diary entries made by a woman whose husband and brother—both doctors—agree on what she should do to overcome a lingering case of nervousness: nothing. At their insistence, she is cooped up in a bedroom of the country estate the couple has rented for the summer—a chamber dominated by wallpaper of “a smoldering, unclean yellow.” As time wears on, she becomes obsessed with that wallpaper and the figure she sees creeping around behind its busy pattern, and far from improving, she gets steadily worse.

Before the story reaches its wrenching climax, the husband cites the originator of the rest cure by name, as a threat. “If I don’t pick up faster,” the patient notes, “he shall send me to Weir Mitchell in the fall.”

Weir Mitchell himself, meanwhile, was at the height of his multifarious powers: treating patients, doing science, advising Penn’s administrators, giving speeches, being a husband and father, and writing more novels. There were to be 13 in all, and toward the end of his long life they were republished in a handsome series of “Author’s Definitive Editions,” with embossed covers, gilt-edged pages, spacious margins, and tissue-protected illustrations by Howard Pyle, one of the era’s leading practitioners. (Merely to thumb through one of these volumes is to be struck by the sensory deprivation of reading an e-book.) William Dean Howells was a fan of Mitchell’s, and the critic Thomas Bailey Aldrich argued that there were two great American novels, Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter and Mitchell’s Hugh Wynne, Free Quaker (1896).

Hugh Wynne centers on the conflict between pious Quaker fathers and their restless sons in Revolutionary War-era Philadelphia. (Mitchell himself was raised Presbyterian.) While trying to decide whether to join the Continental Army in defiance of his father, a prosperous trader, the patriotic Hugh wanders down to the waterfront. Ships owned by the family firm, he notices, are outfitted with cannon and stocked with cutlasses and muskets. “I ventured … to ask my father if this were consistent with non-resistance,” Hugh reports. “He replied that pirates were like to wild beasts, and that I had better attend to my business; after which I said no more, having food for thought.” The young man ends up enlisting.

Like In War Time, Hugh Wynne hurtles from scene to scene without a great deal of focus. It was a best-seller just the same. Mitchell wrote several other historical romances, but his best fiction is about quotidian life in his own era. In Circumstance (1901), he came close to producing a novel of suspense in the manner of Victorian master Wilkie Collins, author of The Woman in White, The Moonstone, and many other books. It’s the story of a comely gold-digger, the well-named Mrs. Hunter, who infiltrates a rich Philadelphia family as a paid companion and tries to inveigle its vain, increasingly childish patriarch into changing his will to lavish money on her. In cruder hands, Mrs. Hunter might be a one-dimensional baddie, but Mitchell gives her a bracing light-heartedness. “She had a fondness for social adventure and a pleasure in small intrigue such as many men have in field sports.” Occasionally, however, the author succumbs to an unfortunate temptation: mounting a soapbox to make sure we know he condemns Mrs. Hunter and her machinations.

No such tendentiousness mars the unjustly neglected Constance Trescot (1905). Early on we learn that the title character, a young wife, is single-mindedly devoted to her husband, George. “Oh, I am a fine fool of love,” she tells him. “I am half jealous of the company you find in your pipe.” At the same time, having been brought up without religion, she has never embraced the Christian virtue of turning the other cheek.

Leaving their native New England in 1870, the newlyweds relocate to the Mississippi River town of St. Ann, Missouri, where George will practice law and manage real estate owned by his wife’s uncle. The locals, whose Confederate sympathies are still strong, don’t accept these Yankees readily. But Constance works hard at ingratiating herself, George persuades the uncle to tone down his obduracy toward squatters on his land, and the newcomers are settling in nicely when the erratic John Greyhurst, who has lost a lawsuit against George, shoots him dead on the street.

Now comes the meat of the novel, in which Constance sets out to avenge herself on Greyhurst, who has just enough of a conscience to be rattled by her mind-game tactics. At least some of the time, Greyhurst believes himself justified in having gunned down George Trescot; even so, Constance’s imaginative, inexorable pursuit leaves the killer shaken again and again. Perhaps owing to his medical training, Mitchell was able to depict these two and the novel’s other main characters with a clinical detachment that seems altogether modern; his sketches of the townspeople and their interactions with the Trescots are sure-handed; and he adroitly brings to life the court case that precedes the shooting. With nary a misstep in its almost 400 pages, Constance Trescotdeserves to be reissued, read for pleasure, and taught alongside such other works of revenge as Medea, Othello, and Wilkie Collins’s No Name.

Constance Trescot also militates against the temptation to write off its author as just one more 19th-century male chauvinist. His rest cure may have infantilized those who took it, but in prescribing it he drew on received wisdom, and he deserves a better fate than being a footnote to the career of Charlotte Perkins Gilman. No one who reads his finest novel can doubt that S. Weir Mitchell knew all about the power of a determined woman.

Dennis Drabelle G’66 L’69 is a contributing editor of the Washington Post Book World.