He didn’t find the Open Polar Sea he was looking for—and probably overestimated how far North he actually managed to get—but the Arctic discoveries of Isaac Israel Hayes M1853 helped set the course for later explorers. And that was just the first of his several careers.

By Dennis Drabelle

For a short time in the mid-19th century, a Penn Medical School diploma doubled as a credential for Arctic exploration. In 1853, Elisha Kent Kane M1842 led an expedition to Greenland and beyond on a search for a missing British explorer [“Explorer in a Hurry,” Mar|Apr 2008]. In 1860, Kane’s former medical officer, Isaac Israel Hayes M1853, mounted an Arctic expedition of his own, with the main goal of discovering the rumored ice-free sea that was supposed to ease the way straight to the North Pole.

Despite failing to find his man, Kane returned a hero, embellished his fame by writing a bestselling book about his exploits, and triggered a nationwide binge of mourning when he died of a heart ailment in 1857, at age 37. Though Hayes made less of a splash, he set the course for subsequent Arctic explorers. He went on to run a hospital during the Civil War, to earn a living by lecturing and writing, and to serve multiple terms as a member of the New York State Assembly.

Doctor, explorer, CEO, public speaker, author, legislator—Isaac Hayes excelled in a remarkable number of roles. He deserves to be better known.

Hayes was born in 1832 to a farming family in Chester County, Pennsylvania. After attending the local public school until age 13, he was sent to Westtown School, a Quaker boarding school of such austerity that its disapproval of frivolous literature extended even to Shakespeare. It was a good incubator of scientists, however. Another of its pupils was Edward Drinker Cope, who became a renowned paleontologist (and taught the subject at Penn). Even without the Bard, Westtown must have been to Hayes’s liking: upon graduating, he stayed there two more years as an assistant teacher of mathematics and civil engineering.

Hayes was leaning toward the study of law when his father talked him into medicine instead. The young man entered Penn’s Medical School in the fall of 1851. As a student he was ambitious, if not traditionally so. “I had a lot of intuitive feeling that my destiny would lead me to the North,” he recalled, “and under the influence of this feeling I set to work the harder and graduated a year earlier than I otherwise would have done.”

Toward the end of his abbreviated stay at Penn, Hayes wrote a letter to Kane, offering his services as medical officer on his imminent rescue mission to the Far North. (Kane’s own Arctic career had begun with a stint as ship’s doctor on an earlier voyage.) The interview went well—and the Penn connection couldn’t have hurt—but an offer was not immediately forthcoming. Hayes hedged his bet by opening a medical practice in Philadelphia and trying to latch on to John Charles Frémont’s planned expedition to the Rocky Mountains. The arrival of a brief note on May 26, 1853, saved Hayes from casting his lot with the inept Frémont: “Dr. Kane would like to see Dr. Hayes as soon as possible.” A whirlwind week later, Kane’s ship left New York harbor with the 21-year-old Hayes on board.

Up north, Hayes looked and learned, especially from adaptations by Eskimos (as the Inuit were then called) to their uncompromising environment. He also tended to patients, notably after the return of a party sent out to lay depots on Canada’s Ellesmere Island. Temperatures bottoming out at 75 degrees below zero had left the sojourners severely frostbitten; despite Hayes’s best efforts, three of them died. On a happier note, Hayes and another man made it to Ellesmere and back by sledge, filling in blank spots on the map.

Bent on exploring some more, Kane decreed that the expedition would spend a second winter in the Far North. Yet fuel and rations were running so low that he gave everyone a choice: stick with him or head south with a portion of the supplies to live on. To his dismay, eight men—a majority—elected to leave, Hayes among them. Their journey proved so harrowing that the famished secessionists were reduced to eating lichen scraped off rocks. In desperation, they turned around and retraced their steps, all the way back to the mother ship. Hayes was chosen to deliver the plea for mercy. “We have come here, destitute and exhausted,” he told Kane, “to claim your hospitality; we know that we have no right to your indulgence, but we feel that with you, we will find a welcome and a home.” They knew their man. Although hurt and resentful, Kane not only took the prodigals in but also surrendered his bunk to Hayes, who had to undergo the amputation of three frostbitten toes. The reconstituted group abandoned ship and made its arduous way back to Greenland on sledges and boats. In October of 1855, they finally reached New York, where they were welcomed as symbols of America’s coming-of-age: it was no longer a country to be explored, but one that engaged in exploring.

Hayes lectured about his just-concluded adventures at the Smithsonian Institution, the American Geographical Society, and lesser venues. Although the talks were well received, audiences found one aspect of them disappointing: the speaker himself. A reporter described him as “quite a young looking, slender, black haired, dark complexioned gentleman, rather under the medium size, [who] does not, at first sight, appear like one of those robust men whom we naturally picture to ourselves as the best fitted to encounter the rigors and hardships of polar navigation.” Ultimately, however, that slight specimen became, as Douglas W. Wamsley puts it in his invaluable 2009 biography, Polar Hayes, “the most prolific lecturer and writer on the Arctic in the nineteenth century.”

Kane’s death left Hayes eager to return to the North at the head of his own expedition; but with no support from the US government and little from the philanthropist who had bankrolled Kane, it took him three years to raise the roughly $30,000 he needed. (In the process, he alienated the only woman he ever loved, who told him he had could have her or the Arctic, but not both.) He furthered his cause by following up on Kane’s great book, Arctic Explorations, with one of his own, Arctic Boat Journey in the Autumn of 1854, about the Kane expeditionary schism. In June of 1860, the Hayes North Pole Expedition finally set sail. Its objectives were to increase scientific knowledge of the Arctic, reach the Open Polar Sea, and, conceivably, steer a course all the way to the North Pole.

In Greenland, Hayes supplemented his crew with Eskimos, including one who had taken part in the Kane expedition. The Eskimos were crack hunters, and Hayes depended on them to keep his 20-member party supplied with fresh meat. They performed well enough that no one fell victim to the condition that had plagued Kane’s party: scurvy.

Hayes’s plan was to cross Smith Sound from Greenland to Ellesmere Island via sledges pulled by dogs, with a boat strapped to one of the sledges for eventual launch into the Open Polar Sea. But the dogs kept dying, and the terrain—if that’s the right word for an immense jumble of ice slabs and hummocks—was so intractable that often the explorers had to climb, descend, zigzag, backtrack, and plod ahead all day long just to advance a mile or two. The thermometer recorded temperatures in the minus 60s, a zone where snow on the ground hardens, causing friction and hampering progress. Luckily one of the Eskimos knew how to cope with this condition: melt ice in your mouth and drool on the sledge’s runners, where the liquid formed a slick ice coating.

Even so, the trip proceeded at such a petty pace that Hayes was driven to distraction. The food supply dwindled, game became unavailable, and he finally had to admit that the best he could do was use clues from his surroundings to infer the existence of the Open Polar Sea. In a morose frame of mind—and with fingers that may have trembled in the profound cold—he took measurements with a sextant to estimate the latitude where he and his men had to turn around. The figure he wrote down, 81° 35’, brought him some solace: at least he’d attained a new farthest north—that is, a point closer to the Pole than any previously recorded.

Or had he? Almost everyone who has since looked into the matter believes that Hayes made a self-serving mistake, overestimating his forward progress by a good 100 miles. The main evidence comes from his own journals, where his descriptions of the landscape fail to jibe with the position he claimed to have reached. To the end of his life, however, he clung to his belief in that farthest north.

Much as Hayes yearned to go on, it was impossible—he and his men were too weak from hunger. They made a long, gloomy retreat, getting back to Greenland in the summer of 1861 only to be told that the United States had fallen apart. So preoccupied were most Americans with the Civil War that the expedition’s arrival in Boston a few weeks later went virtually unnoticed.

The Hayes Expedition may have failed on its own terms, but then they were impossible terms to begin with: there is no Open Polar Sea (although global warming may soon contradict that statement). Hayes managed his men well, collected some interesting fossils, and successfully introduced photography to Arctic travel. He also wrote evocatively about his experiences, including the isolation that clamps down on a person during the months-long Arctic night:

“Silence has ceased to be negative … I seem to hear and see and feel it. It stands forth as a frightful spectre, filling the mind with the overpowering consciousness of universal death … Its presence is unendurable. I plant my feet heavily in the snow to banish its awful presence—and the sound rolls through the night and drives away the phantom. I have seen no expression on the face of Nature so filled with terror as THE SILENCE OF THE ARCTIC NIGHT.”

And the expedition had legs, if you will. Not only did Hayes ignite the late-19th-century craze to discover the North Pole, but his methods influenced Robert Peary, among others. Peary took Hayes’s route northward—possibly all the way to the Pole in 1909, though this remains a matter of lively debate—and emulated Hayes by relying on Eskimo solutions to Arctic problems. (In a world that swore by a rigid hierarchy of races, Hayes’s willingness to learn from a “primitive” people had been exceptional.) The most important legacy of the Hayes Expedition, in short, was to point the way to others, who followed it with greater success.

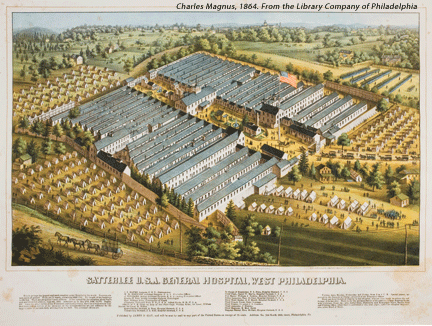

After that somber re-entry to civilization, Hayes gradually won recognition for his achievements. When he sought a position with the Union Army, President Lincoln himself took an interest in the matter. In 1862, Hayes was named director of Satterlee, a government hospital being built in West Philadelphia to treat wounded Union soldiers [“Penn Fights the Civil War,” Mar|Apr 2011].

There was no rulebook for managing federal hospitals, so Hayes had to improvise. The core of his staff was a group of Roman Catholic nuns, the Sisters of Charity, who proved to be reliable and industrious. By all accounts, Satterlee was a model institution that rose to the occasion when casualties arrived by the wagonload from such bloody battlefields as Second Bull Run and Gettysburg. Gettysburg posed a special challenge. In addition to thousands of Union soldiers, the hospital took in 175 wounded Confederate prisoners of war; when space inside the buildings ran out, the overflow had to be housed in tents pitched on the hospital grounds. With hardly a day off, Hayes stayed on the job until the war’s end. (Shortly afterward, the property was sold to a developer, who tore Satterlee down.)

Hayes now moved to New York, where he took care of a long-deferred task: writing an account of his Arctic expedition, The Open Polar Sea, which came out in 1867. Though he was honored by foreign geographical societies, at home the Civil War had all but erased his exploits from memory, and the book’s sales were middling.

Hayes hoped to return to the Arctic, where he might nail down his Open Polar Sea theory and even conquer the Pole itself. As a means to these ends, he proposed founding a colony of explorers, who would abide in the North for years on end, making forays until the ultimate prize was won. However, he settled for an advisory role on a pleasure cruise to Greenland in 1870. He relished reconnecting with friends from previous trips—Danish administrators of the island and Eskimos alike—and wrote a book about the excursion.

By now Hayes was nearing 40, making a modest living as a lecturer and author, and slipping into the role of Arctic éminence grise. When Congress asked his opinion about funding a polar expedition being assembled by an eccentric Cincinnati newspaper publisher named Charles Francis Hall, Hayes expressed grave reservations. Having run across Hall on several occasions, Hayes considered him a bumbler, especially compared with Hayes himself, who would have been glad to take charge of a federally sponsored expedition. Congress ignored Hayes’s warning, with dire results. Hall’s leadership was so erratic that up north a mutinous subordinate got rid of him by administering a fatal dose of arsenic. (The consensus at the time was that Hall had died of natural causes. Although Hayes publicly surmised the truth, he was not to be vindicated until a century later, when Hall’s body was exhumed and tests were performed.) Afterward, the expeditionary ship became separated from 19 of its crew members, left marooned on an ice floe, on which they drifted helplessly south for six terrifying months before being rescued.

One effect of the Hall fiasco was to dampen American enthusiasm for Arctic exploration. Asked by a newspaper reporter in 1875 whether he intended to lead another northern expedition, Hayes replied: “I cannot say that I really expect to, for I am not rich enough, and I have never found anybody willing to make the needed sacrifice. After the disastrous voyage of [Hall’s vessel], I hardly think the Government would aid another expedition.”

Later that year, Hayes reinvented himself as a politician when he ran on the Republican ticket for an open seat in the New York State Assembly. Winning handily, he soon became known for his efforts on behalf of society’s less fortunate members. In an exchange with a colleague who begrudged spending state money on insane asylums, Hayes made a cutting reply to a request for more information: “While I can give the gentleman … information, I cannot undertake to give him either heart or understanding.”

Meanwhile, a British Arctic expedition ended prematurely when most of the participants came down with scurvy because their leaders had ignored Hayes’s recipe for warding it off. At the same time, they called into question both his attainment of the farthest north record and the existence of the Open Polar Sea. Hayes defended himself in print, and the ensuing battle of words ended in a draw.

Assemblyman Hayes built a reputation as an anti-Tammany Hall Republican with an independent streak. Perhaps his most notable political effort was to push for construction of a railroad tunnel linking New Jersey with Manhattan under the Hudson River, a project that came to fruition a generation after his death.

Physicians tend to be autocratic, as do hospital administrators and leaders of expeditions. Hayes, of course, was all three. Re-elected several times (to one-year terms), he began to lose patience with the ponderousness of the legislative process. In exasperation, he berated witnesses at hearings and even snarled at his own colleagues (the irascibility may have been caused in part by the heart trouble that eventually killed him).

Six years after it started, his political career came to a sudden end. The streets of Manhattan had become so filthy that citizens rose up and formed an independent group to lobby for creation of a separate street-cleaning department that would report directly to the mayor. Hayes and other Republicans objected that the proposal would give too much power to the incumbent mayor, a Democrat. The New York Times sided with the reformers, and the dispute degenerated into scurrilous name-calling. The Times went so far as to suggest that Hayes’s opposition derived from a devious and ghoulish motive: he wanted poor people, who voted heavily Democratic, to die from diseases picked up on the putrid streets because Republicans would thereby gain an edge at the ballot box. Widely criticized as an obstructionist, in the fall of 1881 Hayes was pressured by his own party into not running again.

Late that same year, he died after a brief illness. When his relatives came up from Pennsylvania to settle his affairs, they discovered that he owed back rent on his apartment. They were able to retrieve his papers, but little else. It was a sad finale, but not an ignominious one. In an era of influence-peddling, bribery, and boodle, Hayes stayed clean. He parlayed his medical degree into, first, the Arctic adventures he craved and, then, into a vital non-belligerent contribution to the Civil War. He leapt from one important job to the next and performed at a high level in each. Not quite 50 when he died, Isaac Hayes packed a full lifetime of leadership into his relatively brief time on earth.

Dennis Drabelle G’66 L’69 is a contributing editor of The Washington Post Book World.