It isn’t easy for Dr. Dilys Winegrad Gr’70 to single out the exhibitions she is most proud of during her 25-year tenure as director and curator of the Arthur Ross Gallery, which came to an end last month when she retired. Having been present at the creation, and having headed the gallery since it opened its doors in February 1983, she’s proud of quite a lot of those shows—and with good reason.

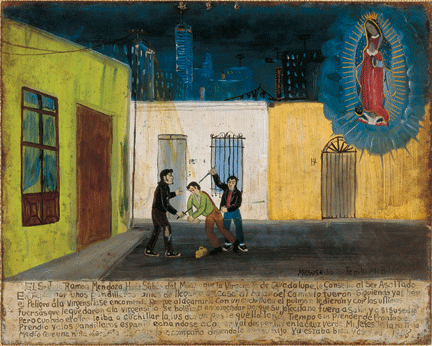

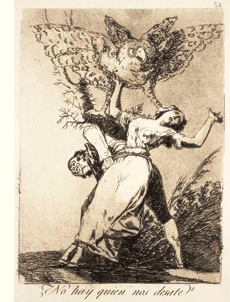

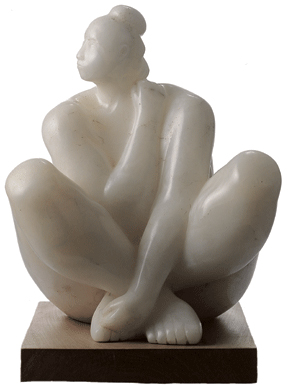

To name just a few: The triumphant “Treasures of Uzbekistan” [“Silk Across the Sands,” Jan|Feb 2000], certainly the “most crazy,” in terms of the mad scrambling needed to pull it off on very short notice, but arguably one of the best and most unique exhibitions ever to grace such a modestly funded gallery. The French Impressionist show (“City Into Country”), which took 10 years of persuasion to pry certain gems from the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The first Henry Moore exhibition ever mounted in Philadelphia. Not to mention some of the remarkable shows featuring works from the private collection of the late Arthur Ross W’31 Hon’92 himself, including the exhibition of Goya’s Caprichos that he loaned twice to the University: first in 1981, when the works were displayed in Van Pelt Library’s Rosenwald Gallery, and again in 2006, when a similar sampling of the first-edition prints [“Arts,” Nov|Dec 2006] were displayed in the gallery whose renovation Ross had funded.

Ross died this past September, five months after longtime supporter Kitty Carlisle Hart passed away. The combination of their deaths and Winegrad’s retirement brings the first chapter of the gallery to a close; as the Gazette went to press there had been no announcement of her successor, though the search is under way.

“I think the next step for the gallery is very hopeful,” said Winegrad. “Arthur Ross was really not at all happy—not to say aghast—at the idea that I, at my tender age, would be thinking of retirement, since he was hardly retired himself. But I assured him, and the University president assured him, that there would be a full search and that they would replace me with somebody at least as good as me —and a good deal younger.”

Furthermore, Ross’s recent gifts to the gallery have made it possible “not just to leave the thing solvent but to leave it in good shape,” she notes, “with some fabulous shows that we’ve been able to do because we’ve had a little extra.” She cites “Treasured Pages: Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts from the Free Library of Philadelphia,” which ends January 6, as an example of an exhibition that “couldn’t have happened before” because of the costs.

Keeping Ross “involved to the end has been wonderful,” she said, “and it gives us, I hope, a good basis for the future.”

Running a limited-budget gallery tucked into an obscure space off the Fisher Fine Arts Library (originally constructed to house the Shakespeare collection of Howard Horace Furness) requires a number of talents, not the least of which is nimbleness. A collector might have a unique collection of work that he or she is keen on displaying. A faculty member might have a connection with a foreign museum eager to display its holdings. The ICA or the Penn Museum might be contemplating an exhibition that inspires a complementary show on campus. And, of course, Winegrad herself has come up with some ideas that not only involve terrific art but also give students and even members of the nearby community a chance to be involved, such as “Leaving a Mark: The Art of the Print in 19th-Century France” [“Arts,” Mar|Apr 2002] and “Master Drawings (1800-1914) from the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford” [“Arts,” May|June 2004].

Though the gallery didn’t open until the tenure of former President Sheldon Hackney Hon’93, the groundwork was laid when Winegrad was working as a special assistant to the late President Martin Meyerson Hon’70, who believed that Penn needed a broad-based University gallery.

“Martin had always felt that the fourth dimension, after whatever the other three are, was the arts,” Winegrad recalls. From the beginning, the gallery’s mission “was that this should be an educational tool” for the entire University community, and Ross supported it with the understanding that it was “not to be associated with any one subject matter or school or department.” A significant part of her job was to intuit what exhibitions would inspire him to support them.

It all boils down to what Winegrad calls “the art of the possible.”

“I think perhaps if I have strengths for this particular position, it’s an almost intuitive [ability] to see things falling in place in a certain order, where we are eclectic,” she says. “Different media, different audiences: all of the people, some of the time.”

—S.H.