The Arthur Ross Gallery marks 40 years by returning to its founder’s favorite.

Dreams of flight have surfaced in European art at least since Leonardo da Vinci drew plans for a human flying machine around 1490, but few artists depicted them with the phantasmagorical ambiguity that haunts Francisco Goya’s Modo de volar. Created in the late 1810s but not published until 1864, long after the Spaniard’s death, the print envisions men in bird-like helmets beating bat-like wings against a blackened sky, borne in unrelated directions and glowing against the darkness like triumphant heroes—or moths drawn to a consuming flame.

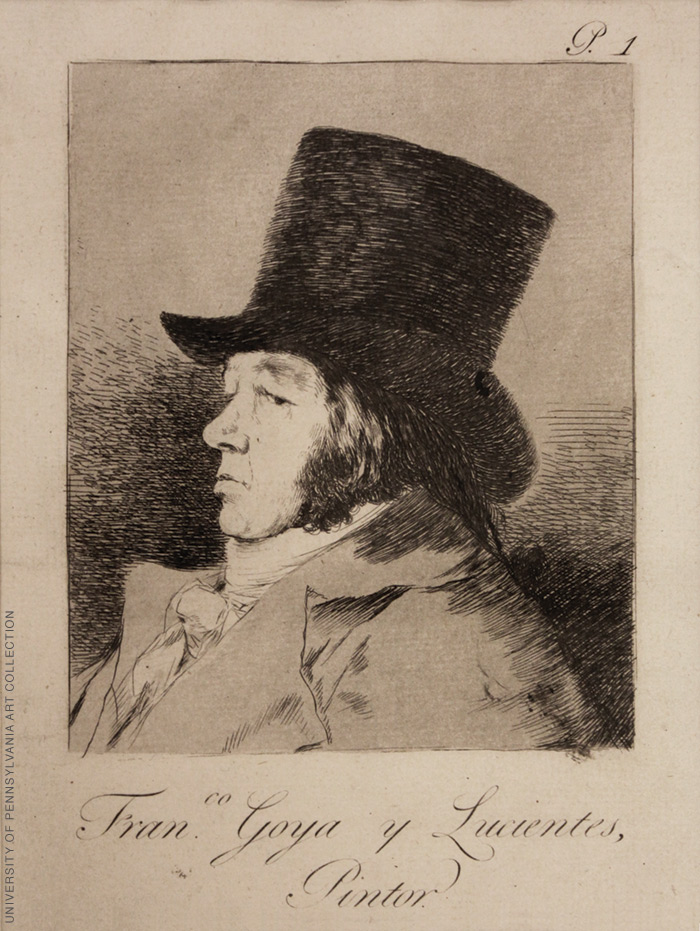

Modo de volar belongs to Goya’s celebrated Los disparates series, which was the first group of prints purchased by Arthur Ross W’31 Hon’92 when the philanthropist began collecting in his 70s. It appeared in the inaugural exhibition of the Arthur Ross Gallery in 1983, and is one of 38 prints on display there through January 7 in a 40th anniversary exhibition titled Goya: Prints from the Arthur Ross Collection.

The Arthur Ross Collection resides at Yale University, to which it was given with the stipulation that Penn’s Arthur Ross Gallery could request the prints on loan. Curators Lynn Marsden-Atlass and Emily Zimmerman chose prints from Goya’s Los disparates and Los desastres de la guerra, whose unflinching depictions of the Peninsular War of 1808–1814—focusing less on heroism than on brutality, famine, and political/clerical critique—may have special resonance against the current backdrop of state violence in places like Ukraine, Sudan, and Yemen. Goya’s “frank and uncensored” approach to the reality of war, noted Marsden-Atlass, distinguished him from his contemporaries.

In that series, as in Los disparates, Goya’s vivid visual language combined with a radical openness to interpretation that marked a turning point in Western art. The ambiguity of many of these images amplifies their intensity—ratcheting up their power to unsettle viewers accustomed to the present fashion for expository artist statements. Goya was a lasting favorite of Arthur Ross. “The universality of his art is evident in the fact that the etchings remain as intensive a visual and intellectual experience today as they were for the artist’s contemporaries,” the collector wrote in a statement accompanying a 2006 exhibition at the gallery. “Goya’s innovations open a stimulating and provocative journey that leads to modern art and beyond.”—TP