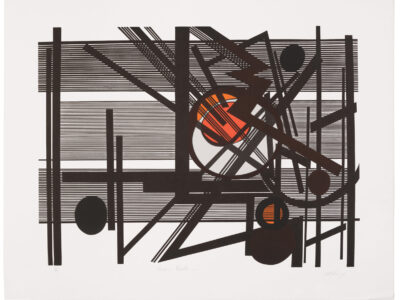

Paper cut with hand-printed color.

At the Arthur Ross Gallery, Barbara Earl Thomas presents Black bodies as transcendent eruptions of light.

“Bodies are like lamps: they are the thing that lights the way. The light of the world comes through the body.”

So declares Barbara Earl Thomas, a Seattle-based visual artist whose larger-than-life figurative cut-paper compositions are the star attraction of an Arthur Ross Gallery exhibition that opened in mid-February and runs through May 21—right after Alumni Weekend. It’s the third and final stop for The Illuminated Body, which was organized by the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk, Virginia, and curated by Chrysler’s Carolyn Swan Needell. The Penn iteration, supported by a grant from the Pew Center for Arts & Heritage, is augmented by programming including a multimedia music performance by Grammy-nominated cellist Seth Parker Woods (presented on April 11 in collaboration with Penn Live Arts), as well as a site-specific installation converting a portion of the gallery into an immersive “Transformation Room” inspired by the marginalia of illuminated religious manuscripts.

Born in 1948, Thomas has long made use of Biblical stories, history, folklore, music, and literature to explore and interrogate “the stories we tell as Americans about who we are.” She has often been drawn to dark themes, such as the racial dimensions of guilt, innocence, sin, and redemption. She described a recent 13-month solo exhibition at the Seattle Art Museum as an attempt to portray “the apocalypse we live in now and narrate how life goes on in midst of the chaos.” But The Illuminated Body is an ode to the creativity and resilience of heroes both public and personal.

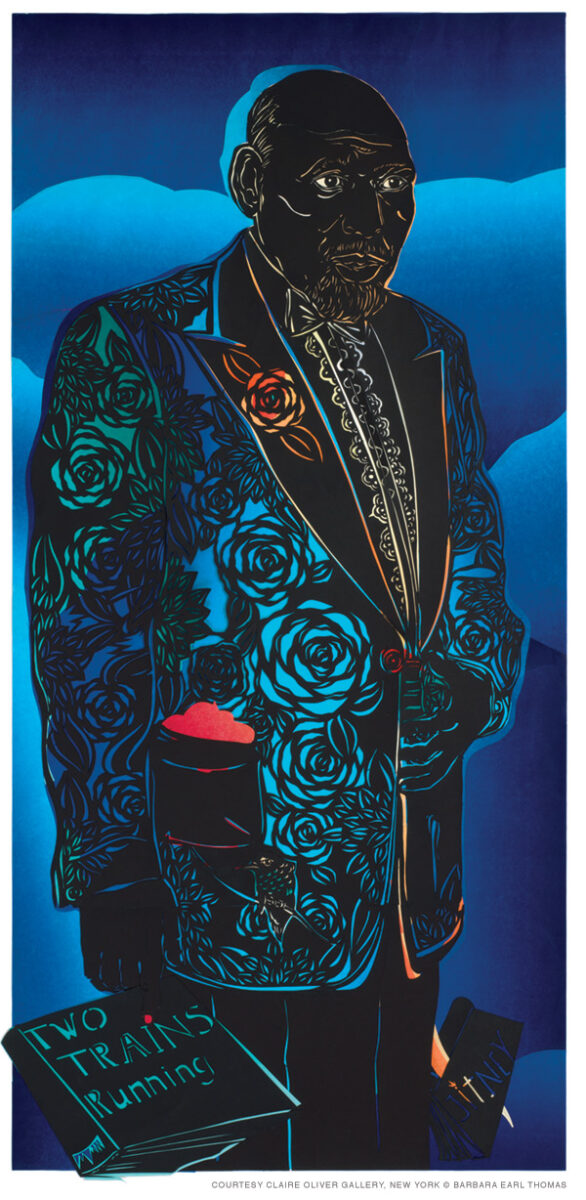

Paper cut with hand-printed color.

In layered paper assemblages up to four-and-half feet tall or wide, she depicts her Black subjects—artists, writers, musicians, and friends—as silhouettes of black construction paper intricately incised to reveal background layers of luminous color which form facial features and clothing details. Floral motifs abound, and her subjects are frequently graced by hummingbirds and tiny detonations of imaginary fire. The jewel-toned colors seem to pulse and glow, as though the works have been mounted on light boxes. But that’s an illusion fostered by hand-printed color gradients, observes Emily Zimmerman, the Arthur Ross Gallery’s interim director of exhibitions and programs. The effect resembles a sort of inverse of traditional stained glass (another medium Thomas is known for), in which skin is represented by ironwork while its boundaries and features appear in dazzling bursts of light.

In an accompanying exhibition catalog, Thomas likens the human body to “a sculptural form that carries its own light emitted in gestures, movements, sighs, and whispers that spill out into the cracks and fissures of the world.” She presents her portraits as “opportunities to move past the skin of our outlines and into the shared light that joins us.”

“Through this exhibition, I wanted to bring to life the idea that despite the challenges we face in modern day society, we find joy,” she said. “The media often portrays Black people as constantly plagued by calamity. The Illuminated Body shows the other side—where strength and hope live.”

The figurative works are complemented by smaller sand-blasted glass vessels and a towering and immersive “Transformation Room” whose walls Thomas fashioned from tall sheets of cut Tyvek. The artist also created new panels to overlay the gallery’s windows, tracing motifs suggestive of Ottoman architecture.

“I’m influenced by moments in history when weapons are exhausted and the cello player appears in the midst of a war-torn Bosnian landscape to play his instrument to no one in particular,” Thomas writes in the catalog, “sending out sound waves not unlike the voices of plague-worn Italians who took to balconies singing; not unlike freedom singers outside an Alabama jail; not unlike the songs of men bound together in a chain gang, syncopated to the metronome of cracking hard rock; not unlike the sequences of dialogue in an August Wilson play or a Charles Johnson novel that capture the meaning of a post-Jim Crow generation and narrate how we’ve arrived in this place and survived.”—TP