The Arthur Ross Gallery’s No Ocean Between Us exhibition explores Asian diasporas in Latin America.

You can rock your “locs” in Jamaica while reserving a different kind of dread for the details of your Chinese heritage. You can embrace the abundance of Peru while noting its conceptual distance from the spare visual language of your ancestral Japan. You can revel in the lush rainforests of Guyana but close your eyes and almost see the trail of sugary tears left behind by your Indian forebears.

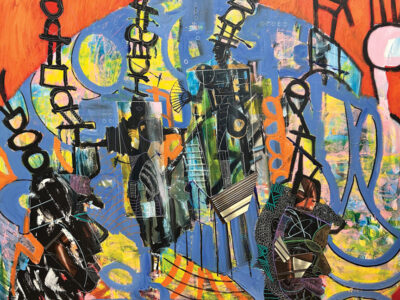

As these artistic dialogues—by Albert Chong, Eduardo Tokeshi, and Bernadette Persaud, respectively—and the others on display in No Ocean Between Us: Art of Asian Diasporas in Latin America & The Caribbean, 1945–Present (Arthur Ross Gallery through May 23) make clear, the past is always present. Culled from a larger touring exhibition, the show was organized by International Arts & Artists in collaboration with the Art Museum of the Americas in Washington, DC. It examines how Latin American artists connected to various Asian diasporas, whether as part of an original immigrant generation or as a descendant of one, have often glanced back while forging ahead.

While the migrations of Japanese to Brazil and Indonesians to the Dutch Caribbean island of Suriname are well known, this exhibition also considers migrations that are not as widely documented. These crossings of Chinese, Indian, Indonesian, and Japanese people to 10 countries (Argentina, Brazil, Cuba, Guyana, Jamaica, Mexico, Panama, Peru, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago)—result in a melting pot of imagery that smudges geographical and cultural boundaries.

“These migrations came in so many waves and involved so many different peoples,” observes Adriana Ospina, director of the Art Museum of the Americas and curator of the exhibition. “It’s surprising that the art that came out of them hasn’t been studied more.” The movements were catalyzed by the early 19th-century abolition of the trans-Atlantic African slave trade, which prompted colonial powers like Britain and the Netherlands to turn to Asia in search of indentured servants. The first of these low-wage workers ended up on the sugar, coffee, and cotton plantations of the Caribbean, Mexico, and South and Central America; later migrants labored in industries like mining and railroads.

The works—mainly paintings—are organized by cultural pairings (e.g. Japan-Brazil, China-Panama) with wall texts that detail the periods of immigration and the artists that emerged from that cross-pollination. “An important element of what we wanted to show was the historical context of the different influxes of workers that flowed into the different countries,” Ospina says. “What paths they took, under which conditions they came, what situations they found themselves in after they arrived. In some countries, they were persecuted, for example. In others, they had a hard time assimilating. Very often they returned to their country of origin. Others remained and settled down in their new homes.”

One of the families that stayed were the Mabes, who in 1934 traveled across the ocean in steerage from Japan with seven children so that the father could work as a contract laborer on a Brazil coffee plantation. By the time the eldest child, Manabu Mabe, was in his 30s, he had earned write-ups in Time magazine and been awarded the title of Best National Painter in Brazil. He is represented here at the Ross exhibition by Agonia (1963), a large, abstract composition of organic red and brown forms on a black background offset by a trailing line that echoes Japanese calligraphy.

oil on canvas.

Other works by the Brazilian issei (first-generation Japanese immigrants) on hand—all members of the influential Japanese Brazilian artists’ collective Grupo Seibi-Kai—are nearly monochromatic but more vividly tonal works. These include Blue and Black (1969) by Kazuo Wakabayashi, the exhibition’s opening work; Verde (1972) by Tikashi Fukushima, and a gestural canvas (Untitled, 1968) by Tomie Ohtake that features two washes of purple in brushwork that harkens to Zen Buddhist paintings.

The bulk of the artists on view, however, are offspring of immigrants. These later generations are often more confrontational about the past, looking not so much to bridge that yawning gap of an ocean between old and new but to come to an uneasy reconciliation. Suchitra Mattai G’01 GFA’03, for instance, has roots in the wave of Indian migrants who arrived in British Guyana more than a century ago to work as indentured servants. Her dynamic weaving El Dorado After All (2017) typifies her work’s exploration of women artisans and colonialism. Examining the textile heritages of India and Guyana, it interlaces the colors of their national flags with tropical blues to form an outline depicting a possible location of the mythical kingdom of gold.

Other artists are more direct in their commentary, incorporating text and stark imagery to get their points across. Bernadette Persaud is another Guyanese artist descended from Indian plantation workers. Her brilliantly hued diptych Wales Sugar Estate—Latitudes of Grief (2016–2017) depicts a verdant terrain on one side and a dark turbulent sea on the other. A timeline marking significant dates (1948’s violent crackdown on striking sugarcane workers; 1964’s riots) is dotted with skulls and phrases like “Day is a burning whip” and “I taste the bitter world.” Albert Chong, the son of Chinese Jamaican merchants, also inscribes language (including Chinese pictograms) in the copper frame of his photo assemblage My Jamaican Passport (1990). “I was given as a sacrifice to build a black man’s hell and a white man’s paradise,”one sentence declares. The image itself is of Chong’s passport resting under a coiled strand of puka shells and open to a page bearing his dreadlocked portrait.

Lima-born Eduardo Tokeshi offers an equally telling but gentler take on dueling national identities in Las casitas de fe (Altares) (2016). A juxtaposition of two wood dioramas, it pairs a crammed-to-the-rafters Peruvian retablo (a folkloric box that recreates religious or historic scenes) with an unadorned butsudan, a Buddhist altar found in Japanese households. The silent contrast between these houses of the holy—of the minimal and the maximal, of the orderly and the chaotic—speaks volumes about the two worlds that tug at Tokeshi.

The exhibition presents a diversity of ethnicities and styles, but the ultimate takeaway is in the distinctly different ways that each artist has reckoned with the past, exploring the legacies of family heritage and cultural complexity. Some chafe at the history behind their blended cultures, others celebrate it by merging these influences, and still others keep the two coolly compartmentalized—separate but equal in their hearts.

—JoAnn Greco