A rare exhibition of artifacts from Uzbekistan at the Arthur Ross Gallery offers a tantalizing glimpse of the cultures along the Silk Road. So did a symposium at the University Museum.

By Samuel Hughes | Photography by Candace diCarlo

Sidebar: Treasures on View: The Genesis of an Exhibition

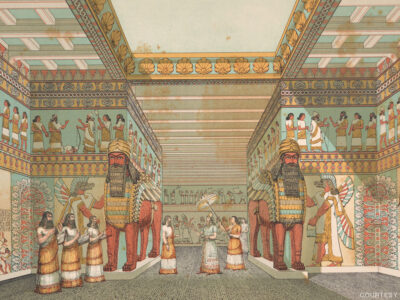

It stretched nearly 5,000 miles across some of the most inhospitable deserts and steppes of Asia. Yet in many areas it was not really a road at all but a series of desert oases, which served as stepping stones and way stations for the ancient traders of Assyria and Bactria and other forgotten civilizations. Along it, caravans of camels bore the riches of the East—first lapis lazuli and tin, then porcelain and, of course, silk—and in the process helped cross-pollinate emerging cultures. But while the route’s origins go back more than 4,000 years to the Bronze Age, it was only in 1877, long after its heyday, that German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen—the Red Baron’s uncle—gave it the “Silk Road” moniker. The name stuck, and resonates still.

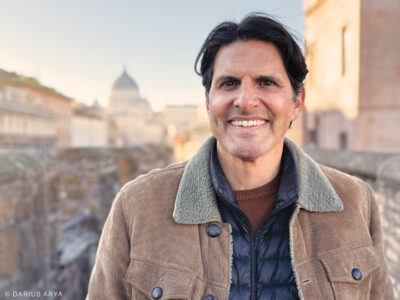

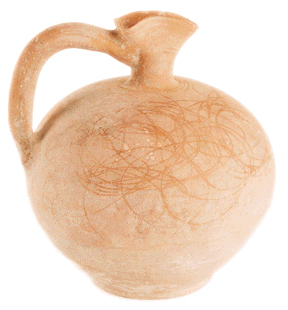

Some exotic remnants of that route can be seen in these pages and in “Treasures of Uzbekistan: The Great Silk Road,” a rare exhibition of artifacts that opened at the Arthur Ross Gallery in November and runs through Feb. 13. The exhibition is the product of a frenetic year’s assemblage by Dr. Fredrik Hiebert —the Robert H. Dyson Assistant Curator of the University Museum’s Near East Section and assistant professor of archaeology—and by Dr. Dilys Winegrad, director and curator of the Arthur Ross Gallery. (For more on that, see page 27.) In the view of Hiebert, who was given a special decree from the president of Uzbekistan to borrow from every museum and institute in that nation, the exhibition represents “our first step in building a cultural bridge between Uzbekistan and the United States.”

Hiebert’s passion for ancient trading routes and patterns has led him to digs in Uzkekistan and neighboring Turkmenistan, as well as to the Black Sea [“Gazetteer,” July/Aug] and its environs. He also organized a scholarly symposium titled “Unraveling the Silk Road” that was held at the University Museum a few days after the exhibition’s opening.

One of the symposium’s scholars, Dr. Victor Mair, professor of Chinese literature, suggested that the route could just as easily have been called the Jade Road or the Bronze Road or even the Wool Road, since all of those commodities were, for many centuries, transported along it. But in the view of Dr. Brian Spooner, professor of anthropology and curator of the Near East Section of the University Museum, the name was not just a matter of “inventiveness” or the “particular orientation of one geographer.” Rather, he said, it has to do both with the nature of silk itself and the “way we classify the world.”

“There just aren’t many other things that link the east of Asia with the west of Asia so obviously and directly” as silk, said Spooner. While the other materials mentioned may have been found along the same route, “they’re not commodities that started at one end of what we understand to be the Silk Route and moved all the way to the other.” Given the difficulties of transportation, only “relatively light and relatively expensive” things were likely to be transported regularly. “Silk was obviously such a commodity.”

The physical environment has always been “a very big player” in the formation of the Silk Road, said Hiebert, while Dr. Renata Holod, curator of Islamic Art in the University Museum’s Near East Section, put it another way: “In a sense, geography is destiny.”

Spooner pointed out that there was a continuous route “from very early on” that stretched from the “interior of China to the west of Asia, to the Mediterranean.” The location of it “shouldn’t really surprise us,” he added, “because if you look at the relief map of Asia, any sort of long-distance movement is likely to be channeled along exactly that route. And there are obviously other places where it could branch off to connect it with major seats of human history on either side.”

It was approximately 2,000 years ago, he explained, during the Han Dynasty in China, that silk became the major commodity on the route that would bear its name. Buddhism was then spreading out of India, and Christianity would soon spread west from the Middle East to Europe.

“It’s in that period when silk begins to become historically important, because it gets out of China and becomes a commodity that is gradually known as far as the Mediterranean,” said Spooner. “It is one in a long line of commodities coming out of the East into the Roman Empire—when people got used to the idea that exotic, very interesting things that one should pay a lot of money for come from the East.”

After the seventh century A.D., the route’s desert oases began to reflect the influence of Islam, and by the medieval Islamic era some of them had evolved into such great cities as Samarkand (built upon the ruins of ancient Afrasiab), which Hiebert described as a “center for law, religion and the arts.” During the 18th and 19th centuries, he noted in a recent article for Expedition magazine, “power shifted to the oasis lords—the khans of central Asia, renowned for their wealth.” And in the 19th century, as Spooner pointed out, “the Russian Empire moved south, and was to draw its boundaries at those oases.”

While the great caravansaries of old are a distant memory, Hiebert suggested that there may soon be a “new era” for the Silk Road, thanks to the discovery of vast oil and natural-gas deposits in central Asia. “When that oil is finally able to make it out of those countries,” he said, “we are going to see a reorientation of our concept of what is Asian commerce, and we will see that this area—which used to be known for silks and porcelain, and before that for lapis and carnelian and tin—will once again become the crossroad of Asia.”

SIDEBAR

Treasures on View: The Genesis of an Exhibition

By Dilys Pegler Winegrad

On Nov. 8, “Treasures of Uzbekistan: The Great Silk Road” opened at the Arthur Ross Gallery in the presence of a distinguished delegation from Tashkent. Guest-curated by Dr. Fredrik Hiebert, the Robert H. Dyson Jr. Assistant Professor of Anthropology, the show includes more than 300 rare objects in a range of media from over four millennia of Uzbek history and culture.

The first such exhibition organized in the United States came about as a result of an edict promulgated by President Islam Karimov of Uzbekistan. This Ukaz gave Professor Hiebert, whose archaeological investigations in Uzbekistan date from graduate work at Harvard, a free hand to select material.

The first of many challenges—and the least intractable in a scenario that often combined extreme suspense with high comedy—was finding a place for the exhibition. Museum schedules are normally in place months and years in advance, but the Arthur Ross Gallery’s repertoire includes efforts to accommodate brilliant proposals from Penn’s gifted faculty in its mission. Major tinkering with a schedule fully subscribed through the end of the 2000-2001 academic year became necessary. Besides being at too-short notice and too fraught with hazard, however, the idea was irresistible.

Subsequent problems ranged from how many Philadelphia venues might be possible—we ended up with just one—to the diversity of objects from five museums in Samarkand and Tashkent, none of whose directors or curators ultimately traveled to the United States for the opening. On a whirlwind visit to all the loaning institutions on his way back from excavations at Black Sea sites in August, curator Hiebert set aside approved objects for packing and shipping to Philadelphia. Yet in mid-September, when I was finally able to travel to make last-minute arrangements, I encountered little regard for the Uzbek phrase ohirgi mudatt: deadline. As e-mails flew at ungodly hours between hotsam@ online.ru (Hotel Samarkand) and Hiebert@SAS, it became evident that if objects were to arrive in time for installation, it would be through the intervention and persistence of Ambassador Sodyq Safaev and his staff in Washington. The entire undertaking succeeded only, in Fred Hiebert’s estimation, through adam gar chalik—the helpfulness of friends.

The evening of Nov. 8, before the crowd moved across the street for a performance of top dancers and musicians from Uzbekistan in the Harrison Auditorium, the ambassador and guests were welcomed by University Provost Robert Barchi. Taking time out from the exhibition, they sampled plates piled high with plov (pilaf) prepared by chefs imported for the occasion. Professor Hiebert’s unerring eye for detail alone ensured that some food would remain for the tired performers.