A three-year digitization and cataloging project made nearly 700 Islamic manuscripts freely available to scholars—and everyone else.

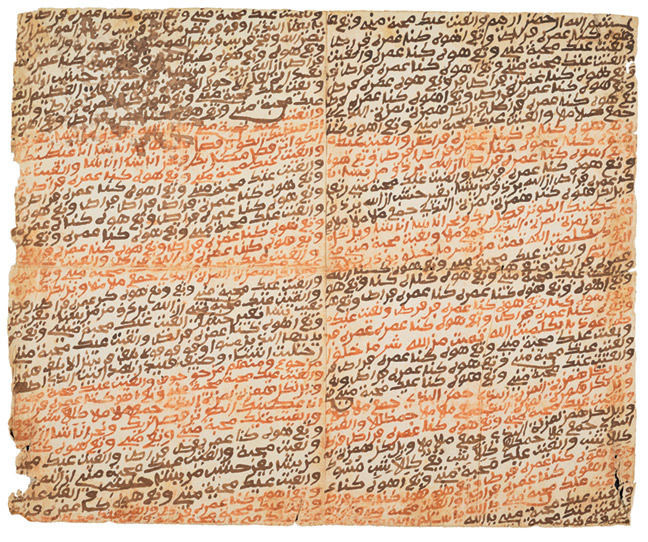

The talismanic charm dating from the mid-1700s—a single large leaf, designed to be folded, containing “repeated verses of the Qur’an in Arabic as well as bits of the West African Soninke language rendered into Arabic script”—was not the oldest item in the Manuscripts of the Muslim World project. Nor was it “the most brilliantly illustrated or textually significant” artifact in the collection, said Mitch Fraas, director of special collections and research services at the Penn Libraries. But it “really defines the power and promise of projects like this one [to] tell us something about the past.”

In a Zoom presentation celebrating the completion of the three-year digitization and cataloging effort, Fraas explained that the manuscript was created (or at least owned) by an enslaved Muslim in Haiti (or possibly Jamaica), and since 1785 had been part of the collection of the Library Company of Philadelphia. Its inclusion among the 684 bound volumes, single leaves, and scrolls dating from 1000 to 1900—including illuminated manuscripts; copies of the Qur’an and Hadith; works on mathematics and the sciences, history and philosophy, law and religion; and written in many different languages—exemplified the wide net cast in the effort, a collaboration among 10 Philadelphia institutions and Columbia University. “The goal was not just to digitize the most beautiful or the most well-known manuscripts,” Fraas explained, “but to reveal the entirety of our manuscript collections related to the Islamic world, writ large, to a global audience.”

Among the Philadelphia participants, Penn (including the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts; the Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies; and the Penn Museum) and the Free Library of Philadelphia were the main players, accounting for most of the materials scanned. Bryn Mawr and Haverford colleges also made their collections available at the start, and the Library Company, Philadelphia Museum of Art, American Philosophical Society, and Temple University joined in along the way. The New York connection came about because Penn and Columbia, contemplating similar proposals, decided to join forces rather than compete for $500,000 in grant funding from the Council on Library and Information Resources’ Digitizing Hidden Special Collections and Archives program.

Thanks to the project, some 216,000 pages totaling more than 10 terabytes worth of data are now accessible online for scholarly research, use in classes, and to the general public through the University’s OPENN portal, as well as the Internet Archive and individual participants’ websites. In Philadelphia, most of the digitization work was done by the Penn Libraries’ staff of camera technicians—who were among the handful of employees with permission to work on site during the pandemic.

But the grant also provided funding to develop detailed catalog information on the collections, which had been sorely lacking. “We had some typed notes done by students over the years, or visiting professors who had come to see an item, but nothing was searchable online,” said Fraas about Penn’s materials. “The only way you would know we had a lot of these manuscripts would have been by asking someone and them happening to remember.” (One of his PowerPoint slides showed a sample notation: Beige Shoe Box, Manuscript C.)

“A big part of this was the ability to hire someone, for the entire duration of the project, as a full-time expert Arabic and Persian cataloger.”

Cataloger Kelly Tuttle made about 500 entries personally, and enlisted graduate students and other volunteers to flesh out information. Volunteers also assisted with cataloging works in languages Tuttle didn’t know, which turned out to be “a substantial number, because we were being really universal in our scope,” Fraas said. “We had Coptic and Syriac and Avestan and Tamashek, which is a Berber language. She was able to connect to a network of basically international volunteer scholars, who were like, ‘Oh wow, you have a Berber manuscript? Sure, send me images. I’ll tell you about it.’”

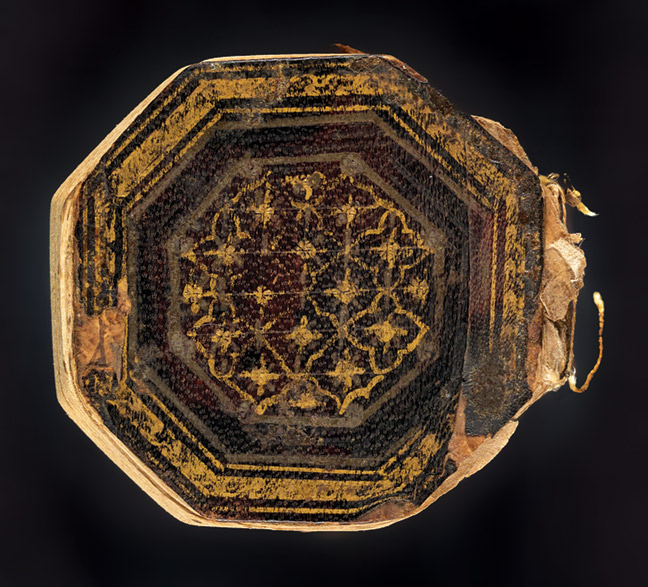

In her presentation, Tuttle also emphasized the project’s broad reach and touched on her experience running its Twitter account. “I’m fairly bad at guessing what would be interesting to folks other than knowing that, um, animals seem to be popular, as are interesting outfits, as are illuminations, especially if they’re fancy, and tweets about Qur’an manuscripts,” she said. Unusual sizes—though hard to communicate via digital image—also get attention. The single most liked tweet, she said, was for “a miniature amulet Qur’an at Haverford College.”

For his part, Fraas said he is drawn to “both the older scientific illustrated masterpieces as well as the mundane but really historically important stuff.” In the former category, he pointed to a “fabulously illustrated” medieval astronomical manuscript from southern Spain during the Islamic period, as well as a “Persian one that has great charts of the color spectrum.” Among the historically significant items were a “fatwa written in the 19th century from what’s now Algeria relating to the French occupation.” Another discovery was a fragment of a “semi-famous” copy of the Qur’an that had been divided up into 30 sections and by “total surprise” turned up in Penn’s holdings.

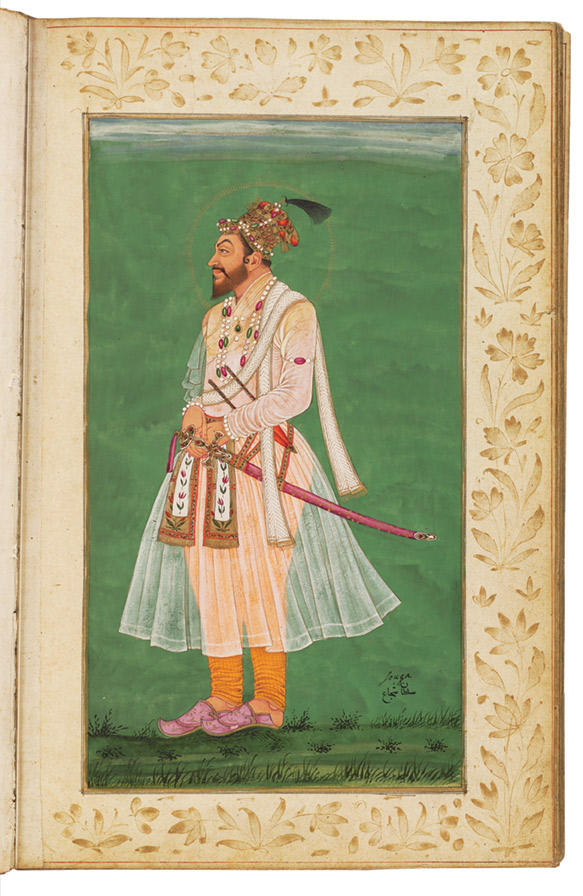

Even items that were adequately documented in the various collections, Fraas remarked, were not exactly accessible before now. For example, among Islamic art scholars, “It was relatively well known that the Free Library had an amazing collection”—but few had seen it. “This has really transformed that, because instead of just being able to say, ‘Oh yes, they have an amazing collection, which I think there’s a list of published somewhere,’ we can actually go and look at, like, an amazing Mughal album that I would never be able to see except maybe in an old art journal with one black and white photograph.”

Though the project is officially over, “I think we feel pretty strongly that if other Islamicate manuscripts turn up in Philadelphia we’re interested in adding them,” said Fraas. They’ve had a few inquiries and plan on “continuing that outreach to other institutions who might have one manuscript or two manuscripts.”

Over the next two years, the Free Library will be doing extensive public outreach to Philadelphia’s large Muslim community. The initial plan had been for coordinated exhibitions of manuscripts from the collection at the Free Library and Penn, but “COVID has sort of messed with our timelines,” he added. “The Free Library is definitely doing theirs. Whether we can do ours at the exact same time is sort of up in the air.”

While the primary users of the collection are likely to be scholars pursuing their own research, Fraas highlighted its value for classroom teaching. “The audience for these now is no longer just sort of hardcore scholars who know exactly what they are doing. We’ve really opened it up to undergrad classes, beginner grad classes,” he said. “And even in an Intro to Islam class at Penn, having the digitized images encourages physical use, because our faculty might say, ‘I had no idea you had this amuletic scroll. Can you bring it out?’” —JP