Thanks to a newly digitized Penn Libraries research portal, singer and civil rights icon Marian Anderson “will be reintroduced to her city and the world.”

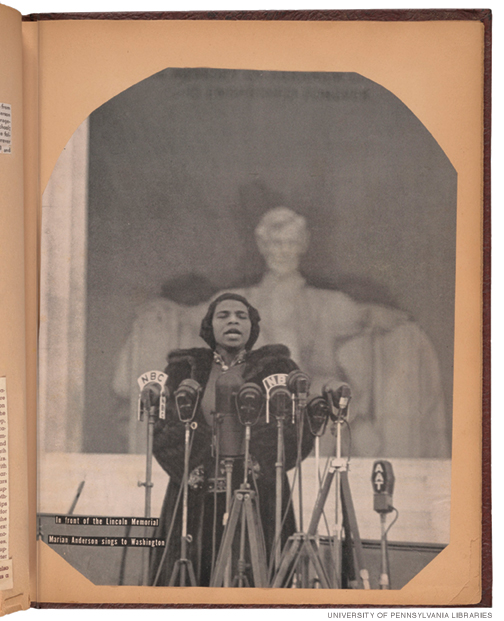

On Easter Sunday 1939, Marian Anderson Hon’58 descended the steps of the Lincoln Memorial and walked right into history. But there’s a lot more to the story of the Black Philadelphia-born classical singer who so triumphantly delivered a concert that day in front of a crowd of 75,000, after being denied an opportunity to perform at a venue owned by the Daughters of the American Revolution.

And now, those interested in further exploring her groundbreaking five-decade career—from the minutiae of her daily life to her interactions with music luminaries and world leaders—can dig deeper than ever, thanks to the recent digitalization of thousands of items from her collection at the Penn Libraries’ Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts. Available through the new Discovering Marian Anderson research portal, the effort was funded by a $110,000 grant from the Council on Library and Information Resources.

Anderson made her first gift of materials to Penn in 1977, at the encouragement of her nephew, conductor James De Preist W’58 ASC’61 Hon’76. Over the years, more donations followed and Penn now holds a vast quantity of ephemera and recordings. Up until now, researchers—including filmmakers working on the 2019 documentary Once in a Hundred Years: The Life and Legacy of Marian Anderson, and on an upcoming American Masters production on PBS—have had to sift through the piles of music manuscripts and concert programs, boxes of tapes, and reams of scrapbooks and notebooks in person.

The 2,500 or so digitized items represent about a tenth of the entire collection, but there’s plenty to dig into. The notebooks alone contain scribbled shopping lists, jotted expenses, reminders of people to call, drafts of speeches, and playlist rosters. “Combined with the concert programs, these materials provide ‘day in the life’ peeks at a traveling musician on the road, in hotels, on trains,” says David McKnight, director of the Rare Book and Manuscript Library. “Scholars can knit all of this together in interesting ways. For one thing, we’re hoping to create an interactive map of her performances. Or maybe someone will do content analysis to determine which songs she performed most.”

The general public thinks of Anderson (1897–1993) as an opera singer, but when she began her career, “opera wasn’t a viable option for Black singers,” says April James, reader services librarian at the Kislak Center. As she pages virtually through Anderson’s programs, she adds, “but she did sing operatic selections—I’m looking through one program from a 1935 concert in Russia and there are three Handel arias right there.”

An opera singer herself, as well as a specialist in women composers, James points out that Anderson was very receptive to submissions from contemporary female composers, such as Florence Price, who often rearranged traditional African American spirituals for the performer. “In some of the scores, you can see Price’s notes to Anderson, asking her if something would work for her voice,” James says. “You see the composer tailoring the song to the singer.”

Recordings of these works turn up in the digital archive, of course, but so do taped interviews such as a series of conversations with New York Times critic Howard Taubman, conducted as preparation for My Lord, What a Morning, the Anderson autobiography he ghostwrote.

“There are several unexpurgated interviews that are interesting for the enormous insight they provide into her Green Book-like experiences on tour,” McKnight says. “Although she was regarded as a very important, iconic figure in the civil rights movement, she rarely spoke publicly about these issues. She was a very politic woman.” Listening to the tapes, we hear the reporter gently press for more memories and more details. The singer at first demurs, distancing herself from the scene with repeated uses of the pronouns “one” and “we.” Gradually she opens up with several anecdotes, adding that she remains keenly aware that because of her status, she was often protected from the worst Jim Crow offenses. “Exceptions are made for one person and that one person knows that there are so many others who are just as good, just as fine a character, who are submitted because something about them hasn’t been shouted to the housetops.”

In a later interview—this time for the New York classical music station WQXR—she revisits another event that would define her career almost as much as the Lincoln Memorial performance: her debut at the Metropolitan Opera. Despite finding extraordinary success in Europe (where she’d sung the work of Finnish composer Jean Sibelius for him at his home and won the praise of Arturo Toscanini, who dubbed hers the “once in a hundred years” voice), she says her “greatest dream” remained to sing on the Met stage. It wasn’t until 1954 that she received an offer to do so. “My heart was beating so loudly that I didn’t know if I was going or coming,” she recalls of that moment. “I tried to answer as nonchalantly as the question had been put to me.”

The performance, in Verdi’s The Masked Ball, was her only operatic stage role and it came in 1955, relatively late in her career. But the distinction of breaking that particular color barrier was the beginning of a long succession of honors for the star, including singing at the presidential inaugurations of Eisenhower and Kennedy, an appointment as an alternate delegate to the UN General Assembly, and inclusion in the first group of artists to receive the Kennedy Center Honors, which debuted in 1978.

Anderson always preferred to “let her excellence be her activism,” James says. “That’s her true legacy. With so much of her collection now online, I hope she will be reintroduced to her city and the world.

“If she hadn’t paved the way, would it have even been achievable for Black opera stars like Leontyne Price, Kathleen Battle, and Jessye Norman to get to the Met stage? And would the spirituals have become part of the concert repertoire? All of this would have taken so much longer, and maybe not have happened at all.”

—JoAnn Greco

To explore the Discovering Marian Anderson portal, visit mariananderson.exhibits.library.upenn.edu.