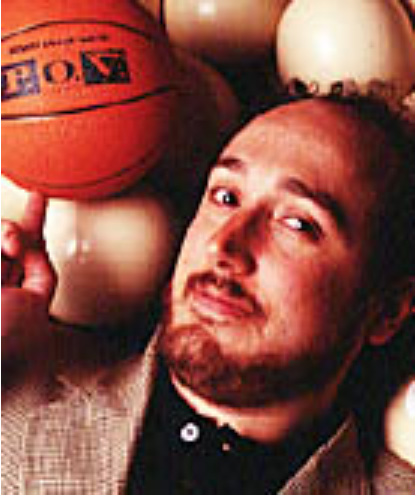

The letters P.O.V. were once synonymous with I.O.U. Today the fledgling men’s magazine, co-founded by a Penn alumnus working off his laptop, has multimillion-dollar backing, an office equipped with its own bar, and a new nightlife supplement called Egg.

By Susan Lonkevich

LARRY SMITH, ASC’91, hadn’t spoken to Randall Lane, C’90, since the two of them were keeping late nights at 34th Street and The Daily Pennsylvanian. Then one day three years ago he turned on his answering machine and heard a familiar voice saying, “Hey — I’m starting a magazine. You probably haven’t heard of it because it’s new … ”

The magazine that Lane was creating back in 1995 was P.O.V., and a lot of people have heard of it now. Named AdWeek‘s start-up of the year, the “guy’s survival guide” with the work-hard, play-hard philosophy currently draws a circulation of 260,000. Once assembled with “tape and bubblegum,” a stack of credit cards, and a host of IOUs to former Penn writers like Smith, P.O.V has since received a multimillion-dollar investment from Freedom Communications that has allowed it to be run “like a real magazine.”

Its creators are so confident now, in fact, that they’ve launched a new product this month, a nightlife supplement called Egg.

“My partner [P.O.V. publisher Drew Massey] and I both worked at Forbes,” recalls the 30-year-old Lane, “and neither of us saw a magazine out there for professional young guys like us. GQ and Esquire were skewing a little bit older and fancier, and then we had Details for guys in their twenties, which seemed to glorify not having a job and piercing your nipple. There was no magazine that spoke to us, so we figured we’d just do it.”

P.O.V., says Lane, “is a complete lifestyle magazine,” and it tackles such diverse subjects as on-line trading and tequila, ski resorts and startup companies, birth control and business suits. The average reader is a man in his late twenties with an income of $50,000, but some 20 to 30 percent of readers are women. (In fact, Lane and Massey had considered creating a magazine for young professionals of both sexes, but after consulting with experts, realized that they needed a focused audience and advertising base to be successful.) Good timing has been another ingredient in P.O.V.’s success, he believes. “I think 10 years ago this demographic might have been a little more consumerist. This is about living life to your fullest. It’s a real magazine. I think we’re living in a real decade. It’s not as much about what you have as it is about what you’re doing.”

These days, P.O.V.‘s not only selling copies, but earning some praise from the pros. “It’s fun, I think it’s smart. I think they’ve carved out their own niche,” says Eliot Kaplan, C’78, editor of Philadelphia magazine, another publication brimming with the bylines of Penn alumni. “They’ve got pretty good people on their cover, and it’s a nice-looking book. And as much as I like GQ and Details and Men’s Health, I think it’s an alternative to them. I also think it’s great that all these Penn guys are there doing it.”

OF THE 800 TO 900 new titles launched annually, half will sink within the first year, according to Samir Husni, an associate professor of journalism at the University of Mississippi who publishes a well-regarded annual guide to emerging magazines. “Only three out of 10 remain in business after four years.”

But Husni believes P.O.V. “is one of the success stories that we can talk about, especially since they were able to get Freedom Communications to put in the money ($15 million over five years in exchange for ownership of half of the publication). That is essential to keep any successful magazine surviving. So many other magazines started in a similar style, like Might and KGB and Tribe, and they were all aimed at the same market, but they did not have the money to stay in business. P.O.V. does not have that problem.” It also targets a much broader audience than those other men’s magazines did, Lane believes. “None of those had as much mass-marketing appeal.”

The fact that Lane was only 27 when he started P.O.V. is not so unusual, Husni says. Look at Time magazine, which recently turned 75. Henry Luce and Brit Hadden founded the news weekly just three years after graduating from Yale, and a spate of much newer magazines, including Icon, are also edited by twenty-somethings. “Age is not important anymore. We’re seeing more and more of these kids publishing. It’s the easiest mass medium to get into, and the cheapest of the printed mass media, if you don’t count the Web.”

If anything, Lane perceives his youth as an advantage. “When we first started the magazine, we saw a [now-defunct] publication called Your Future, which was put out by Money magazine and edited by a woman in her fifties for people in their twenties. Think about the name, Your Future. If we put out that magazine, it would be called Our Future. From the editor on down, they didn’t get it. When we put out P.O.V., it’s very easy for us, because we’re speaking to ourselves in some way. We’re speaking to our friends and to our peers.”

They found an appreciative audience. Tommy Leonardi, C’89, a photographer who coauthors P.O.V.‘s sex and relationships column, says, “When Randall came up with the idea for this magazine, the perception in the media was that people in their twenties were these unguided Generation-X slackers (a term that Lane hates). People loved to stereotype us that way, but my friends weren’t slackers and Randall’s friends weren’t slackers. He put together a magazine that was targeted at an audience he knew existed, but no one in the magazine industry seemed to recognize at the time.”

LIKE LEONARDI, MANY of the writers willing to crank out stories in the early days were Daily Pennsylvanianveterans — a fact that Lane, the DP‘s former managing editor, hasn’t forgotten. Today, three of the magazine’s full-time editors (Larry Smith, Ed Sussman, C’88, and Cheryl Della Pietra, C’91) and half a dozen of its regular contributors are Penn grads, most with DP ties.

Smith, a former 34th Street editor who held a series of writing and editing jobs on the West Coast before plunging full-time into P.O.V., recalls that Lane “gave me two days to write a story on how to buy the ultimate stereo for under $500.” He knocked it out, and about a month later, he received “some random check” and an I.O.U. for the remainder of the money he was due: (“We’re a little low right now …”) His patience paid off, and he’s now a senior editor, in charge of editing the “Leading Off” section of the magazine, the on-line version of P.O.V., and Egg.

“I’m a very loyal person,” says Lane. “These guys were with me when we were nothing. They took a chance on me, so now I think it’s only appropriate that we dance with the ones who brought [us] here.” Working under someone he went to school with, Smith says, has been “absolutely fun. Under different circumstances it certainly could be awful, but it’s not a big ego place. And he’s a buddy, so we go talk about stories over beers and music.”

The Boston headquarters of B.Y.O.B./Freedom Ventures, Inc., where Lane and the rest of the editorial and circulation staffs have worked up until now, are in a former fraternity house with its own foosball table. But they were expected to consolidate and join their colleagues on the sales and marketing staffs in New York by this month.

Those who toil in characterless cubicles may have dreamed of something like P.O.V.‘s club-like Manhattan office in the funkily fashionable neighborhood of Chelsea. After you pass the unassuming bakery storefront and ride a creaky elevator up to the ninth floor, you emerge into a closet-sized hallway papered with multiple images of Tyra Banks, arms swept across her breasts, and Matt Dillon, glowering over his goatee — promotional posters of past P.O.V. magazine covers. Press a buzzer and you’re let into a spacious office that instead resembles a place where you might want to pass a Friday evening. Perhaps it’s the cozy arrangement of overstuffed velvet couches and armchairs in shades like garnet red and burnt orange, the oak pool table, or the satellite TV poised over a bar stocked with Bombay Dry Gin — perfect for mixing martinis — and other libations. For alternative thirsts there are two locally-brewed ales on tap. Lane points to an empty space where bands sometimes perform. “The acoustics are good.” But though it may not appear to be an office in form, it is one in function. No one is sidling up to the bar this Monday morning, and actual work appears to be taking place behind the screens, where the desks of the sales and marketing staffs are concealed.

“It’s designed to create an environment that mirrors our magazine,” Lane says. “We use it as a marketing tool and we save money by not having to rent spaces every time we throw parties to entertain clients. We entertain the writers there as well. I always resented working at magazines where you would never be invited to any of the parties. It pays off, because people appreciate your doing things differently.”

The same philosophy that went into the unusual office design applies to the editorial product itself. “The key to doing a P.O.V. story,” says Lane, “is doing it in a way that has never been done before.”

IN FACT, HE SEEMS to have always had the knack for developing distinctive story ideas. One might be hard-pressed to find a Penn freshman who didn’t edit his or her high school newspaper, but Lane arrived on campus with a more unusual credential, a clip from The New York Times. He had written an article about waiting out all night for Bruce Springsteen concert tickets. Once on the staff of the DP, he earned the nickname “Scandal Randall” for uncovering hot stories, such as a cocaine bust at The Castle, formerly the home of Psi Upsilon fraternity, in 1987. “It was very heady,” recalls Lane, who might be described as a laidback adrenaline junkie. He became managing editor his junior year, and spent the summer afterward interning at the Wall Street Journal‘s Philadelphia bureau and covering federal courts for the Associated Press.

But an advanced non-fiction writing course with the late Nora Magid, a much revered Penn lecturer, exposed him to other possibilities as a writer. “I saw magazines as a very literary way to do what I wanted to do,” Lane says. He was torn between the thrill of big scoops and satisfaction of writing at “a more cerebral pace.”

After graduation Lane landed another internship, at the San Jose Mercury News. Eager to make an impression, he pitched the idea of trying to join a street gang to the editor of the paper’s Sunday magazine. “I would try to infiltrate the Crips or the Bloods.” As it turns out, neither gang was interested in having an Ivy League graduate tag along with them. “In retrospect it was kind of stupid, but when you’re 21 you’re like, ‘Oh, no problem.’ Oakland’s gangs were way too tough for me, so I went on to the San Jose gangs, which is like the Double A league and the ones in L.A. were like the Major Leagues.” Lane suspects that even these second-tier gang members took him to be an undercover cop, because rather than robbing liquor stores they spent most of their time swilling beer on a couch on somebody’s front lawn.

He did gather enough material, however, to turn in a compelling cover story on graffiti, which helped land him an offer for a full-time reporting job covering the school board. But Lane longed to write on a national scale and soon left for New York to become a freelance magazine writer. He was sharing a postage-stamp sized apartment with Mike Finkel, W’90, and still barely scraping together a living, even with the restaurant reviews that allowed him to eat out and assignments for magazines like Cosmopolitan.

Cashing in on his Journal internship, Lane eventually secured a job at Forbes as a reporter (“glorified fact checker”), and was soon gathering bylines again, covering the sports and entertainment industries and outing the secretly rich. By the time Forbes promoted him to Washington bureau chief, he was already moonlighting for P.O.V.. “I didn’t want to go to Washington because I had become comfortable in New York. But I was 27, and the guy I was replacing was 57. You don’t turn that down.”

In the meantime Lane’s supervisors had given him their blessing to publish his magazine on the side. Massey, who had worked on the business side of another Forbes publication, American Heritage, sold the ads, getting in return insertion orders, which are promises to pay after the ads’ publication. But the printer demanded cash, so they had to take those orders to a factoring company, a “legal loan shark,” says Lane, and procure a loan at 20 percent monthly interest to print the magazine.

That temporarily solved their printing problem, but Lane, who was using his laptop as his office, also needed writers — good ones. That’s where Penn alumni came in, from experienced scribes to those fresh out of school.”I did a lot of IOUs and ‘I’ll take you out for beers,’ and a lot pleading and ‘trust me’ and calling in favors,” Lane says. With no money to spare for promotional parties, they had to create a buzz through the editorial product itself. “So we came up with a story on the 10 jobs to get into and 10 jobs to dump for 1995.” The Associated Press picked up the article; then USA Today followed suit — exactly the publicity they were hoping for. Financial relief came later.

They printed three issues on their own over a period of several months — essentially whenever they had enough money — but both Lane and Massey knew they couldn’t keep the magazine going much longer without some institutional support. “Drew had put $50,000 on his credit cards,” Lane recalls. “I was into debt several thousand dollars. And I couldn’t work two jobs forever.” Lane left Forbes soon after Freedom committed to investing in P.O.V.

LANE IS ON THE PHONE from West Palm Beach, Fla. He is, by his own admission, one of the least proficient golfers ever to tee off, but now he’s gone and enrolled in golf school, willing to risk further humiliation for the prospect of another off-beat article for his magazine. “We tailor our stories to our reader,” he explains. “I’m a horrible golfer. So the angle is, ‘Let’s take the worst golfer and see if golf school can be the magic bullet.'” (For the record, Lane’s score actually got worse, but he improved his form. See P.O.V.‘s May issue). The magazine has spent the day behind the scenes at ESPN, uncovered the top 10 American cities in which to make it rich, and divulged how to be treated like a big shot at casinos. One previous cover story explored how to “beat the system,” with Kato Kaelin offering tips for finagling free rent.

Lane’s old roommate, Mike Finkel, gets to live out what might be many guys’ adventure fantasies — or nightmares — as P.O.V.’s outdoors editor: “I’ve written about anything from the world’s most dangerous bus ride in Bolivia to biking across the United States to the U.S.’s most dangerous job: I spent a couple of weeks on a crab fishing boat in the Bering Sea — in January. It was horrible, but it makes for good reading.” Next, for a change in temperature, Finkel plans to go undercover at a Florida nudists’ colony. “Randall’s wonderful about embracing my oddities. His philosophy is that anything we might be curious about, our readers would be curious about.”

If Kaplan, of Philadelphia, has a criticism of P.O.V., it’s that, “I think they could probably sink their teeth into a story every so often instead of it being smaller things on everything.” Lane says P.O.V. has published some in-depth articles, such as a piece examining whether Kurt Cobain was murdered and a story about cartoonist Ted Rall’s harrowing journey along the old Silk Road, but acknowledges that they’re more difficult to do with a modest budget. “Our bread-and-butter is service journalism, and we have to stay true to that. You can say GQ does great journalism, but they got there because they do such great fashion, and people pick it up because they want to see what clothes they should wear, what fork they should pick up, and how they should tie a bow tie. Once they’ve captured them from that, they can also throw in some great journalism. So we’ve got to do that with the young professional guy. We’ve got to give him the stuff he needs to know, and from there we can go to town.”

How does a younger Penn alumnus who hasn’t written for P.O.V. view the publication? “They’ve really got their moments, such as doing a story about how Prague is over as a hip city,” observes Ross Kerber, C’89, a DP veteran and friend of Lane’s who works as a staff writer in the Wall Street Journal‘s Boston bureau. “They’re always keeping their radar on and are forward looking.” His overall assessment: “It’s certainly the best written of the trashy men’s magazines. How do you define trashy? Trashy is any men’s publication that’s got fashion models strutting around in see-through nylon shirts.”

Lane takes the mixed compliment in stride but says, “We don’t want to be trashy. We want to be a very upscale magazine. The writing’s on a high level, and the advice is on a high level. It’s made to stimulate your brain.”

The gently-frayed seams on the velvet upholstery and the low-tech elevator at P.O.V.‘s office are subtle reminders that it’s still a young magazine with a ways to go. P.O.V. hasn’t turned a profit yet, and Lane predicts it will take until the end of 1999 to do so. “Five years is considered ridiculously fast” for a new magazine, he says. “Seven years is considered good. So we’re shooting for four.”

Husni agrees that “Magazines don’t make money overnight. It’s a long-term investment.” He said the fact that P.O.V. is coming out with new editorial products, like Egg, is a good sign for its survival. But if Smith’s attitude is any indication, the magazine won’t lose its edge even when it starts to turn a profit. “We’re young. We try to get out and push ourselves. I don’t want to go to 17th floor of some big awful corporate building. I guess it could happen one day. This is a pretty well-established, pretty successful magazine, but it’s mellow and there’s no reason for it not to be fun, for it to be stuffy. I don’t think that will change.”

After all, Lane points out, the magazine itself was founded on risk. “I had a good job that I loved, but how many chances do you get to start something that’s yours? When that opportunity presents itself and the window opens, you have to go through it.”