The making and honing of an online literary magazine.

Not long ago, a friend gave Karen Rile C’80 an unusual literary gift: a hand-forged kitchen cleaver. So far, she hasn’t wielded it, though she does occasionally punctuate our email interview with words like Thwack! and Chop! Chop!

“We are not violent, cleaver-wielding people,” says Rile, who teaches fiction-writing at Penn. “Although I think it’s a beautiful object, I’m also afraid to use it. It looks really sharp, in both senses of the word.”

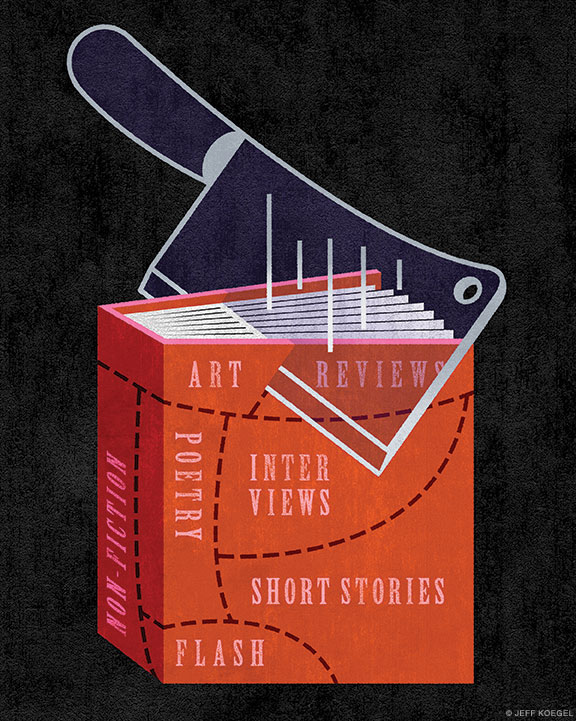

That formidable blade honors the online literary magazine that Rile and her oldest daughter, Lauren Rile Smith, created—with the help of quite a few others, some of them Penn-connected. But there’s more to the name than a keen edge.

“Cleave is a Janus word, also known as an auto-antonym: a word that means both itself and its opposite,” Rile explains. “To cleave means both to stick tight and to fall away. A cleaver is the most broad-edged and brutally efficient kitchen knife. Cleave also means to come together with strong attachment. So a cleaver is something that connects and also slices apart.”

Most writers and artists appreciate the name’s abstract concept, she says. But not all: “We do get a small but continual trickle of submissions from misguided horror writers who clearly have not looked at the magazine.”

Thwack!

Starting a literary magazine had been a topic of conversation between mother and daughter since the late 1990s.

“Lauren and I are both writers and we have a family background in graphic design and arts entrepreneurship, so a project like this seemed natural for us,” says Rile. “At first we wanted to start a magazine for and by children—we were going to call it Flea Circus—and we did a lot of preliminary research into what it would take to publish a magazine.” When Lauren was 14, and already publishing her poetry in literary magazines, she “decided that she wanted to create a lit-mag for adults instead”—to be called Cleaver. But though they both had confidence in their design and editorial talents, the realities of selling and distributing a print magazine were sufficiently daunting that they put it aside.

Fast-forward to late December 2012, when the two were sitting at the holiday table with the rest of their family. “In a fit of mutual brainstorming the idea came to us that we were ready to create an online magazine,” Rile recalls. Both had plenty of literary contacts to solicit for the first issues, and were confident that the magazine’s reputation “would solidify and we would be able to attract high-quality unsolicited submissions.” Both were also skilled at Web design.

“With an open source platform like WordPress, image-editing software, and an online submissions manager, we could make a magazine with a fairly low budget and distribute it far more effectively than we could ever dream of distributing a print journal. Of course we would call it Cleaver. I went straight to my computer and purchased the domain name cleavermagazine.com. (Thwack!)”

In February 2013 they launched a “.05 All-Flash Preview Issue,” which featured tiny poems, ultra-short essays, and flash fiction. The first full issue of Cleaver came out the following month, and they’ve held to a quarterly publishing schedule since; Volume 13 hit the e-streets this past March. They now have more than 3,500 non-paying subscribers who receive the issue by email, as well as many more non-subscribing visitors. A number of the magazine’s pieces have been recognized by The Pushcart Prize, The Best American Essays, and The Best Small Fictions.

Gazette senior editor Samuel Hughes recently spoke with Rile by email.

What are the pros and cons of an online magazine?

The most obvious drawback is that you don’t get a lovely perfect-bound object to hold in your hands while you read. But we were not going to publish a print magazine in the first place, so the objection is academic. We do have a feature that allows readers to click and create a printable PDF of any piece on the site.

The other drawback is that if our internet hosting company goes down for a few minutes, or hours, as has happened occasionally, then the site is dark and no one can access it, not even me. But these blackouts are rare and short-lived. I have multiple backups and excellent security software. I’m also fortunate in that our brilliant art editor, Raymond Rorke C’80, is an internet whiz, so if I run into any thorny problems, he can often help.

On the plus side, we never run out of inventory. We are reaching many more readers than we could have dreamed of with a print edition. Our audience is international; our reach is broad and deep. We are a better magazine, more diverse and more interesting, for these reasons.

How do you reach people who love to read but don’t always want to read fiction or poetry online?

For the purposes of discussion, let’s assume that readers consume print literary magazines in a linear way, cover-to-cover. Online magazine readers do this sometimes, particularly when they first discover the magazine, or immediately following a quarterly issue launch: using our analytics software, I am able to watch them land on the issue cover page, then work their way sequentially through each piece. But more often they land on a specific piece via a Google search, or an author’s website, or a social media post. After reading that piece, they graze through related pieces, perhaps in a specific genre. Or they may leave the site altogether. Some readers only look at the poetry; others are there to read book reviews, etc.

What did you want to not do? (i.e. what magazines really bug you?)

I suppose I am bugged by magazines that are poorly organized, badly edited eyesores. Who isn’t? And magazines—as opposed to blogs—that feature frequent literary content by their own editors. Neither Lauren nor I publish our own writing in Cleaver; a few of our literary editors have had their work featured here, but they came on as editors after publishing with us. (Criticism is a separate category.) For me, work on Cleaver is a completely different kind of creative outlet than my own writing. I think this is true for all of our editorial staff.

How has Cleaver ’s structure evolved?

Our visual aesthetic, which I would describe as quirky/elegant, seemed to come to us organically. But we spent a lot of time thinking about typefaces, color, logos, sidebar widgets, and whatnot. Over the past two years the look has “sharpened” a bit, but the structure and feel is essentially the same.

Our literary aesthetic is pretty eclectic: we prize work that is fresh and specifically detailed, but there are a wide range of styles within each genre.

We take pride in introducing emerging (and sometimes first-time) authors along with more established writers and artists. We also take pride in our gender balance—about 53 percent of our literary authors are women.

In May of 2013 we began publishing frequent reviews of books from small and independent presses, in part as a way to drive readers to the site in between the quarterly releases. Soon, the book-review section took on a life of its own. We currently have five book-review editors, including several Penn alums: Nathaniel Popkin C’91 GCP’95, Michelle Fost C’85, and Tahneer Oksman C’01. The review editors are very hands-on mentors for the young critics who write for us—some have gone on to publish reviews in major newspapers. One recent Penn grad (Jamie Fisher C’14, who also writes for the Gazette) was recruited by the New York Times Book Review based on her Cleaver reviews.

How has the reality differed from the dream?

The magazine has been much more successful and also much more work than we initially imagined. A few months after we started Cleaver, Lauren was hired full-time as the rare-materials assistant at Penn’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library, where she had worked part-time for a few years after graduating from Swarthmore College. This sudden change in her schedule—she is also the founder and director of Tangle Movement Arts, an aerial acrobatics theater company [“Arts,” Jan|Feb 2012]—forced her to cut back drastically on her involvement in Cleaver. While she remains the chief poetry editor in an advisory capacity, most of the poetry selection is now done by other editors, including Zoe Stoller C’18, a Penn sophomore, who is an absolute phenom.

You now have 29 people working for you. Do you need more?

We started with just the two of us, Lauren and me. I guess we did a good job because, as if by magic, wonderfully talented people volunteered to help. Many of them are Penn people. Our staff is large, but everyone does as much as she or he is able—some work only a few hours a month and may disappear for a while when their lives get busy. Others put in quite a lot more time, including some of our young interns. Last year we were lucky to have a Bassini Writing Apprentice funded by Kelly Writers House. Our interns write at least one book review and are involved in selecting and editing work for upcoming issues. I value their input tremendously. Cleaver is a shared project that relies on the generosity of writers, editors, proofreaders, and of course the readers who visit our site and sometimes even leave donations.

How have the quantity and quality of submissions evolved?

We’ve always enjoyed excellent submissions in the so-called slush pile. We have about an 8 percent acceptance rate for unsolicited submissions. The rate will probably drop as we receive more and more. We started out with very strong writers (mostly solicited at first), and therefore we have attracted good writers. Our poetry section is, I think, particularly strong.

How has Cleaver affected your life, literary and otherwise?

I’ve certainly developed an empathy for editors and changed some of my own submissions strategies. It’s also affected the sort of advice I give to young writers, in terms of how to approach literary magazine submissions. I do think that all writers should spend time on the acquisition and editing side of publishing. I’ve also met a lot of wonderful writers through Cleaver and established many new collaborative relationships—that’s priceless.