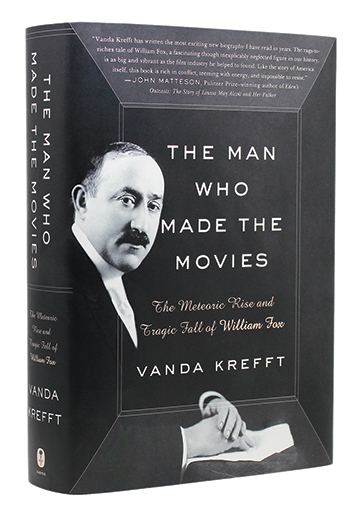

The Man Who Made the Movies:

The Meteoric Rise and Tragic Fall of William Fox

By Vanda Krefft C’76 ASC’01

Harper, 2017, $40.

A new biography traces the life and career of pioneering movie mogul William Fox—a Horatio Alger tale that ended in disgrace.

BY NOAH ISENBERG

Hollywood history, like most history, has often been written from the standpoint of the victors. There’s no shortage of triumphant tales of studio moguls, their ingenious directors and glamorous stars, not to mention the award-winning pictures they made. But the story that former entertainment industry journalist Vanda Krefft tells in her deeply engrossing, scrupulously researched doorstop of a biography, The Man Who Made the Movies: The Meteoric Rise and Tragic Fall of William Fox , isn’t just another heroic yarn spun by the mythmakers of Tinseltown. Rather, it’s an unusually revealing window onto the movie industry during the earliest decades of its existence and a fine-grained portrait, pockmarks and all, of one of the flawed men who created it.

Born in 1879 into a German-speaking Orthodox Jewish family in a small Hungarian village miles northeast of Budapest, William Fox (né Wilhelm Fuchs) was brought to America when he was less than a year old. His family resettled on New York’s Lower East Side, in one of the many impoverished tenements crammed to the roof with newly arrived European immigrants, where his father, Michael, struggled to make ends meet. At the age of 10, William dropped out of school to compensate for the inadequacies of his father, whom he never forgave, working in New York’s garment industry, the so-called “shmatte business,” at D. Cohen and Sons. Three years later, in order to attend his own Bar Mitzvah—his mother had given her son the Hebrew name “Melech,” or king, hoping one day he might pursue a respectable profession—he had to feign illness to get a day off work.

It wasn’t long before the ambitious, young émigré was turning his sights, and his earnings, toward the acquisition of penny arcades and nickelodeons, eventually forging an alliance with a shady Tammany Hall politician named “Big Tim” Sullivan to buy up movie houses (throughout the 1910s he opened theaters in Brooklyn, Manhattan, New Jersey, and New England). “To get where he was going,” writes Krefft just a few chapters in, “he needed to believe in America.” The character arc of Fox’s life story hews for long stretches of his professional life to a kind of Horatio Alger rags-to-riches narrative. “The American is a pusher,” Krefft quotes the essayist and critic H. L. Mencken as saying. “His eyes are ever fixed upon some round of the ladder that is just beyond his reach, and all his secret ambition, all his extraordinary energies, group themselves about the yearning to grasp it.”

Like many of his counterparts among the leading Hollywood moguls—Louis B. Mayer, Samuel Goldwyn, Jack Warner, and Harry Cohn—Fox’s professional achievements were indeed prodigious: He waged an unrelenting campaign to acquire movie theaters at home and abroad, successfully busting up the monopoly on exhibition once held by Thomas Edison in the process; helped launch the career of Theda Bara, one of the earliest screen sirens ( Cleopatra, 1917); contracted the great German director F. W. Murnau, who made his spectacularly acclaimed American debut Sunrise (1927) for Fox; won five out of 12 awards, more than any other studio, at the inaugural Academy Awards ceremony in 1929; and, at different points, employed such A-list directors as John Ford (The Iron Horse, 1924), Frank Borzage (Seventh Heaven, 1927), and Howard Hawks (A Girl in Every Port, 1928). He also made great strides in the arena of film technology, pioneering the sound-on-film (Movietone) format over Warner Bros.’ less effective sound-on-disc (Vitaphone) system, and introducing an early 70 mm widescreen process, decades ahead of its time, called Grandeur.

Unlike the other moguls, however, Fox, who preferred to conduct business from New York and generally avoided spending long periods of time in the glow of Hollywood, wasn’t a skirt chaser or a serial philanderer. (He hated his father for many reasons, but Michael Fox’s infidelities were near the top of the list; when Fox père passed away, in a scene that Krefft recounts at the beginning and once more near the end of her book, his son is said to have spat on his coffin, muttering, “You son of a bitch.”) Fox was forever loyal to his wife Eva, whom he married at the age of 20, in 1899, and stayed married to her until his death in 1952. In most other respects, however, Fox was a loner, operating outside the establishment, maintaining as much control as possible, who was “steeped in the nineteenth-century romantic myth of rugged individualism,” as Krefft aptly notes.

Yet, by the summer of 1929, the professional standing of Mr. Fox was no longer so fantastic. At this point, the story of victory takes on the dark pall alluded to in Krefft’s evocative subtitle. After acquiring a controlling share of Loew’s Incorporated earlier that same year (“This was to be the greatest stepping stone of my career,” he insisted), Fox was poised to become the most powerful mogul in the business. But then fate, or some other force, tripped him up. First came a near-fatal car crash on Long Island, in July 1929, which left his chauffeur dead (while Fox was recovering in the hospital for weeks, the one name kept from the visitors’ list was his father’s). And then in October came the stock market crash, which sent him into a financial tailspin from which he’d never recover.

Fox concocted a specious case for bankruptcy, so flimsy that when it looked all but certain to fail in court, he attempted to bribe the judge. Caught and tried for his actions, Fox was forced to serve an abbreviated sentence in Lewisburg federal penitentiary, in Pennsylvania, in 1942. Half a decade later President Harry Truman granted Fox an official pardon, but as Krefft rightly suggests, “nothing could erase the stain on his character.” When he died at the age of 73, in May 1952, from protracted complications after a stroke, his reputation was beyond repair. Thanks to Krefft’s extremely detail-rich, even-handed biography, he may, now, no longer be forgotten.