New leadership—plus the pandemic and protests—are fueling change at the venerable Penn Press.

The year 2020 was always going to be a time of transition for the 130-year-old University of Pennsylvania Press. It was just last September that a new director—Mary Francis, who formerly held leadership roles at the University of Michigan and University of California presses—succeeded Eric Halpern, who’d held the job since 1995 [“Pressing On,” March 1998]. Then, at the end of January, the appointment of a new editor in chief, Walter Biggins, was announced.

Biggins, who most recently was executive editor at the University of Georgia Press, arrived in Philadelphia two days before the coronavirus-prompted lockdown in March. He has yet to enter the press’s distinctive mid-Victorian building at 3905 Spruce Street as an employee, though he did see it when he interviewed back in December. And except for the people he met then, he’s been getting to know the editors and other staff from the confines of Zoom, BlueJeans, and Microsoft Teams.

But Francis and Biggins are forging ahead with their plans for the press amidst the changes wrought by the novel coronavirus within scholarly publishing—from upending traditional work routines to accelerating shifts toward delivering content digitally and amplifying calls for making more of it available at low or no cost, known as Open Access. They are also assessing prospects for industry changes coming out of the wave of protests sparked by the death of George Floyd and other Black victims of police violence that began in late May. That movement has highlighted the Penn Press’s established strengths in publishing books related to the struggle for racial justice, which Biggins hopes to build upon.

“I’m the kind of person who is very attracted to dynamic environments, and I knew that just my arrival would create some dynamism,” Francis said of joining the press, where Halpern had left his stamp on every aspect of operations. Add in the impact of recent events, and “without me having obviously planned any of this, people will probably look back at my first year at Penn, and [say], ‘Oh wow, a lot of things changed.’”

As director, Francis is responsible for the overall management of the press, which includes a journals division as well as the books program and publishes about 140 volumes annually in the social sciences and humanities. She also serves as the main point of contact with the University administration.

Biggins leads the acquisitions department, overseeing the press’s slate of new books and crafting its overall creative vision. He’ll also continue to acquire books himself in fields including cultural studies, the intellectual and political history of the Americas, the Atlantic World, and postcolonial studies.

Getting used to that “bifurcated” framework has been challenging while working remotely, he said on a video call in mid-June. “Learning the social environment of the Penn Press—how people operate, and who does well with what—has been a learning curve that I wasn’t expecting, because obviously we didn’t have COVID-19 when all of this was being formulated. But we’re in it now.”

Francis described the editor in chief as playing an almost symbolic role in shaping a press’s intellectual identity. Biggins stood out as a candidate because of the way he “hit the highest-level mark” when it came to his ideas about that and about “what’s important for scholarly publishing to be focusing on now,” she said.

As an editor, Biggins has mostly concentrated on “books about the Americas,” he said. At Georgia, he frequently found himself in competition with Penn Press editors for the same books, “so I knew Penn’s list very deeply in that regard.”

He also was attracted to the press’s “engagement with the rest of the world, with Europe, with ancient and early modern cultures,” as well as the opportunity to engage more broadly and deeply with Philadelphia as a subject—something he suggested the press hasn’t taken as much advantage of as it could.

According to Biggins, the pandemic has “amplified” scholarly publishing’s more or less perpetual state of crisis. Brick-and-mortar bookstores, online sites like Amazon, and scholarly and regional libraries are all taking fewer books. “So we’re having to think creatively about ways to publish that are dynamic and still get into people’s hands,” he said. All current and future press books will be available in electronic editions, and they’ve been working to convert as much as possible of the back list as well.

“But we’re also just thinking about new modes of publishing,” he added. Making content available to as many readers as possible “often freely, is something that is really appealing to a lot of scholars—and really difficult for publishers to figure out how to pay for,” he said. “So we’re thinking about those challenges on top of just the regular COVID-19 concerns.”

The flood of research on the coronavirus that has been disseminated ahead of peer review in online forums has highlighted larger questions over accessibility, Francis said. The pandemic “has put a lot of social pressure” on the existing system, in which major scholarly commercial publishers “get very large fees for their subscriptions,” she added. “It has given a platform and more of a megaphone for the people who are out there saying, ‘Why is this not costing less, why are people making so much money on this, when your taxes went to the National Science Foundation to pay for those grants’” to do that research?

Francis, who was heavily involved in Open Access initiatives at Michigan’s and California’s presses, believes that scholarly publishers need to be involved in those discussions, though she admits that the Penn Press “has done no Open Access at all.” That could change in the future, though the question of how to cover necessary expenses remains critical to resolve. “I do think it’s important, but it’s not like a switch that you turn on or off.”

In addition to issues arising from the pandemic, Francis suggested that the ongoing “national dialogue” on “America’s original sin” could lead the publishing industry to “take a look in the mirror” in terms of its own economic, gender, and racial biases.

Publishing is populated mostly by people who are white and relatively privileged economically, she said. “It’s a very hard industry to make it in if you come from a working-class background. It’s also very, very feminized at the entry level but largely male at the leadership level. So, this has been a real moment of self-reflection.”

As a woman replacing a longtime male leader, Francis considers herself a representative of positive change, which she has continued with hires like Biggins, who is Black, and others. “That’s been a real gift, even as it’s happened during a time of struggle,” she said.

Some of the press’s existing strengths speak directly to the current moment, Biggins said. Penn is best known for books in early American history and early modern studies, and also has “a very strong list” in human rights studies, but includes offerings in a wide variety of other disciplines as well—perhaps too many, he suggested.

“We [have] published in so many areas that it’s hard for someone coming to our press cold—looking at our catalog and looking at the website—to know ‘What is Penn’s identity, what is it that they consider themselves really good at?’” He said he wants to strike the right balance between “expanding what people think of as the press but also in some ways contracting the actual things that we acquire.”

Francis pointed to alliances with the McNeil Center for Early American Studies and the Institute for Urban Research, which she hopes to grow, and other potential partners in areas such as human rights. “It’s a way of thinking about expanding, but it’s also about taking your strengths and making them more concentrated.”

Many of the social issues raised by this summer’s protests have been studied and debated in books published by Penn and others, Biggins noted. “A phrase like ‘Defund the Police,’ for instance, which has become very popular—in scholarly circles and within university presses this is not a new idea. These sorts of carceral studies and things like that have been present not only at this press but at a lot of presses that publish on humanities,” he said. “What’s been really galvanizing is to see how the work that’s been produced by university presses is becoming mainstream.”

This is something that the Penn Press has always been good at, he said, “and that I want us to highlight and to think about more and get out into the world more—so in terms of acquisitions and editorial vision, that will continue to be a big part of what we do,” Biggins said. “I think that’s true not just of this press but of any number of presses that do any kind of work on race, any type of work on discrimination, and any type of work on public policy—and we do all three.”

“You hate to feel that you are ready to jump into such a terrible situation, but we were ready,” added Francis.

“Particularly in the books program that Walter is the leader of, we do have contributions to make—not just the books we’ll publish in the future … but also the stuff that we already have ready to go to help people get through this remarkable and challenging, but I think hopeful, moment in the national dialogue,” she said. —JP

Anti-Racism Reading List

Penn Press provided this selection of books relevant to the current movement for racial and economic justice and against police brutality. All can be found at www.upenn.edu/pennpress.

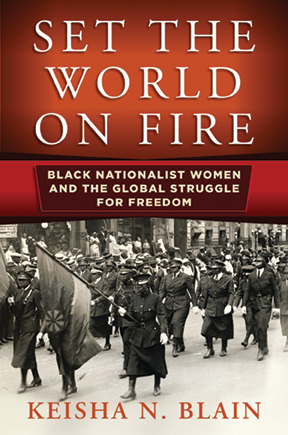

SET THE WORLD ON FIRE: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom by Keisha N. Blain

Highlights the Black nationalist women who fought for national and transnational Black liberation from the early to mid-20th century.

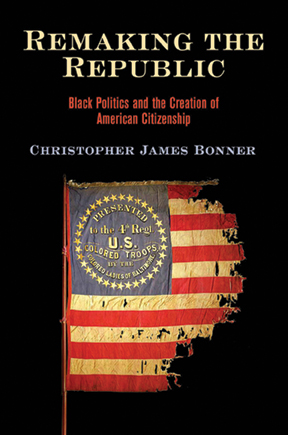

REMAKING THE REPUBLIC: Black Politics and the Creation of American Citizenship by Christopher James Bonner

Examining newspapers, conventions, public protest meetings, and fugitive slave rescues, the author reveals a spirited debate among African Americans in the 19th century, the stakes of which could determine their place in US society and shape the terms of citizenship for all Americans.

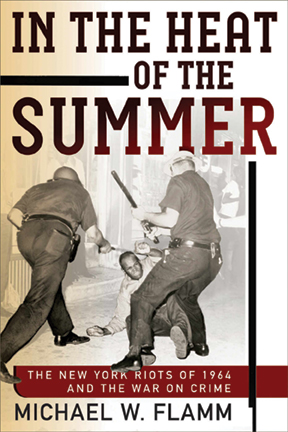

IN THE HEAT OF THE SUMMER: The New York Riots of 1964 and the War on Crime by Michael W. Flamm

In Central Harlem, the symbolic and historic heart of Black America, the violent unrest of July 1964—the first “long, hot summer” of the ’60s—highlighted a new dynamic in the nation’s racial politics.

FORCE AND FREEDOM: Black Abolitionists and the Politics of Violence by Kellie Carter Jackson

In the first historical analysis exclusively focused on the tactical use of violence among antebellum Black activists, the author argues that abolitionist leaders created the conditions that necessitated the Civil War.

POLICE POWER AND RACE RIOTS: Urban Unrest in Paris and New York by Cathy Lisa Schneider

The book looks at the relationship between racialized police violence and urban upheaval in impoverished neighborhoods of New York and greater Paris.