The University of Pennsylvania press has a new home, a new director, and some new goals and projects. It also has a checkered past — and a changing world of publishing to contend with.

By Samuel Hughes

The whine of circular saws the quiet of the old mansion at the corner of 42nd and Pine Streets in West Philadelphia. It’s a strangely impressive edifice that once housed the American College of Physicians and now suggests the marriage of convenience between a French chateau and a mental institute. In the north wing, marble fireplaces and oak panelling conjure up images of Eakins-era surgeons discussing neuralgia over afternoon Madeira. The newer south wing is an anonymous warren of Penn-affiliated offices with flourescent lights and drop ceilings.

A couple of months ago, the University of Pennsylvania Press made the Great Leap Forward from its temporary quarters in the south wing to its venerable new quarters in the north. For Eric Halpern, who took over as the Press’s director two and a half years ago after 12 years at Johns Hopkins University Press — where he rose from senior acquisitions editor to editor-in-chief — the move means more than just classier office space and a permanent address. In a small, symbolic way, he hopes it will send a message that the Press intends to increase its presence in the competitive world of university presses — a world in which the Press has not, on the whole, been a major player.

“The physical setting of a press is very important for its public image,” Halpern acknowledges, a few days after moving into his elegant new office. “That’s why presses hunt out unusual space. When the Penn Press was at Blockley Hall, I think any author coming to that setting would feel that the Press was in sort of second-class status. So this move couldn’t have come at a better time. And I certainly intend for the setting to be matched by the rest of the publishing program — in short order.”

He’s got his work cut out for him. Founded in 1890, the Press does have some impressive titles in its catalogue — a century ago, for example, it published W.E.B. DuBois’s landmark The Philadelphia Negro, while Aaron Beck’s Depression and several of the Press’s medieval- studies books are minor classics. (For some other distinguished titles, see the sidebar at left.) But in its long and often precarious existence, the Press has only produced about 2,100 books, and even now, in a growth period, it is turning out about 75 a year. While that output puts it in the top third of university presses, it is fairly small potatoes compared to the more than 300 books published each year at Princeton, the 250 or so at the University of Chicago, the 220 from Yale, the 175 from Cornell, and the 2,500 from Oxford and Cambridge combined. Size isn’t everything, of course, but it does often have a bearing on quality. And it’s fair to say that the Press has never taken on anything close to the stature of the University itself.

Halpern himself, though bullish on its potential, describes it as a “very small press that has had little in the way of major institutional ambitions at a very major university with very major institutional ambitions.” Later, he amends that slightly: “The Press has always been very good and respectable but very small and very — well, tweedy comes to mind. Certainly nothing of the intellectual or cultural force that a press like Chicago’s or Harvard’s or Princeton’s is at their institutions.”

He is working to change that, within the limits of plausibility. Since the average gestational period for the Press’s books is two to three years — some take a decade to go from gleam in the eye to publication — it will be several more years before his impact can really be gauged. While his retooling efforts have led to some nice media attention and a quiet air of optimism around the Press, most observers agree that it still has a ways to go.

“It’s possible to be a great university and have a modest little press,” says Dr. Edward Peters, the Henry Charles Lea professor of history. “But if you’re Penn, and you’re in a certain league with other universities, I guess there’s an ideal minimum, and that minimum is a little ahead of where we are now. And I suspect that the maximum is going to be the result of a lot of other factors, including the University’s interest [in the Press] and its self-image.” Peters is responsible for the Press’s single most important line of books: its medieval-studies series, which is among the most distinguished of its kind in the country. But, he notes: “It’s a very big tail wagging a very small dog.”

Given the University’s early neglect of the Press, its budgetary constrictions, and the current publishing climate, it won’t be easy to genetically engineer a bigger dog, so to speak. It will have to grow organically, one cell at a time.

“WE’RE trying to pursue our scholarly ends by increasingly commercial means,” Halpern is saying in his pleasantly dry manner over lunch at the Faculty Club. “That is, trying to act like commercial publishers, packaging our books and couching them in a way that will make them seem less formidable and more friendly.”

Thirty years ago, such words might have been viewed as heresy. Today, in a publishing climate of evolutionary belt-tightening, they pretty much reflect the prevailing orthodoxy. As a recent article in The Nation noted, quite a few university presses “have picked up intelligent, general-interest books that trade publishers have ruthlessly jettisoned from their lists,” while other university presses “survive by publishing mainly regional books.”

“You remember the flap over Harper-Collins cancelling a hundred [book] contracts?” asks Halpern. “Well, some people have raised that as the specter of the future — that with the conglomeration of publishing that’s going on, the larger publishers are always going to raise the financial barrier for books. Which means that at some point, important books are not going to be published, because they won’t meet the financial requirements of those presses. So that’s where I think university presses can play a very important role. They can’t pay big advances, but they can guarantee an author some longevity on the list and the kind of prominence on a smaller press’s list that a large publisher couldn’t guarantee.”

John Ackerman, director of Cornell University Press, says it is “the mission of university presses to bring scholarship to a more general audience.” But that isn’t always easily accomplished, he acknowledges. “Since the sixties, scholars have been largely writing for a very professional audience. And they often can’t write. There’s a sort of coin of the realm in each discipline. People learn to talk in that coin, and they often are completely surprised when somebody outside the discipline says: ‘What in the hell are you talking about?’”

Halpern believes that the blurring of boundaries between commercial and scholarly presses can be a healthy thing. “It forces us to improve the books we acquire editorially,” he points out. “Even the scholarly books we acquire, we want to reach as broad an audience as possible. Since we do want to focus on certain fields, the general-interest books in those fields will support the more scholarly or narrower books in those same fields. And it’s usually the more experienced academic authors who begin to write real books as opposed to research papers.”

There is a good deal more to Halpern’s game plan than just tapping into the “mid-list” end of the commercial-publishing market. His first goal is to “enlarge and refine” the editorial program.

“We’re really too small,” he explains. “We need a larger editorial staff; we need to produce more books. Right now we’re so reliant on the sales of — or vulnerable to the lack of sales of — particular books. We need to achieve certain economies of scale, especially in marketing and promotion. We need to be able to spread our risks over a larger range of titles each season — and to do that, we simply need to hire more editorial staff.”

Overall, he’d like to see the Press publishing about 120 books a year, and he notes that the average print run of the Press is around 1,100 copies. “I’m not interested purely in numbers,” he says, “but I am interested in the shape and segmentation of the program. I don’t want to be publishing 98 percent of our books in the softer humanities and social sciences. I want professional and scientific books as well — and a significant percentage of them.” The biomedical sciences, starting with veterinary sciences, are at the top of his list, and he intends to hire an acquiring editor in that realm by this summer. He has his eye on the mother lode of editorial riches at the Wharton School, and within the next few years hopes to hire a history editor to concentrate on American history and books on the Philadelphia area. “This is a region obviously rich in history,” he explains, “and the Penn Press has never taken advantage of that. We’d like to.”

Being a realist, Halpern knows that the Press is never going to be one of the giants of the industry. “It’s a little late in the day for us to grow in the way Chicago or Princeton or Harvard has, since most of their growth took place in the years when there was plentiful funding for university presses and university libraries. But still, given the wealth of opportunities at the University, we should be able to grow significantly and improve significantly.”

To understand why the 108-year-old Press is not a major player in the publishing world, one needs to look at its history as a “fragile offspring” of the University, in the words of Martin Meyerson, Penn’s president from 1970 through 1981 and chairman of the Press’s board of trustees until a few months ago. “Its ups and downs were rather astonishing,” Meyerson adds.

Peters recalls that when he first got involved with the Press back in 1969, its then-director, the late Fred Wieck, told him bluntly: “The University has done every goddamn thing possible to kill it.” The first week of Meyerson’s presidency, Penn’s financial planners — then facing something akin to bankruptcy — advised pulling the plug on the Press altogether as a way of saving money. Meyerson refused, though he was forced to slash its budget. In the late seventies, it was again threatened with closure. “There was again that sentiment, ‘Let’s close the Press,'” recalls Meyerson, “but it was not going to happen on my watch.” He helped reorganize it so that it was a semi-autonomous organization with its own trustees — albeit one still dependent upon University largesse.

In recent years the Press has had steady, if hardly lavish, funding from the University. “When I was there, the support was quite consistent,” recalls Tom Rotell, whose 12-year tenure as director ended in 1994 when he accepted the directorship of the better-endowed University of Texas Press. “It was not the kind of support that the prominent university presses have received,” he adds, “but it was enough to make the Press a decent university press — but not a great one.”

Under Rotell, the Penn Press doubled its output, maintaining the quality of its flagship series in medieval studies; it also continued to be well respected for its folklore and anth- ropology series and a few other small scholarly niches. But of the dozen different areas that the Press publishes in, says Rotell, it has a “leadership role in maybe three.”

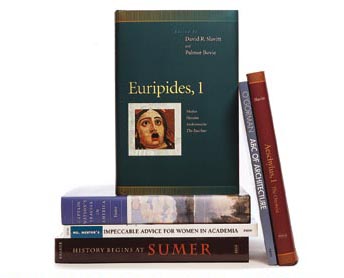

In Halpern’s view, “we need to be viewed as a kind of classy mid-size press,” which is why his second goal is to “enhance the prestige of the imprint and the visibility of the Press.” That translates into “acquiring better books in addition to more books, and doing everything that publishers do a little better.” Early signs have been encouraging. The new Penn Greek Drama Series has been getting terrific press, for example, while James F. O’Gorman’s ABC of Architecture has garnered rave reviews and sold 10,000 copies in its first 10 weeks, putting it on track to be the Press’s all-time best-seller. (Upcoming projects to watch for include the Penn Studies in Landscape Architecture Series, edited by Dr. John Dixon Hunt, chairman of the Department of Landscape Architecture and Regional Planning, and CD-ROM editions of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, edited by Dr. Stuart Curran, professor of English, and James Joyce’s Ulysses.)

Cornell’s Ackerman says that outside of money, the most important thing for a university press to have is “synergy among the acquiring editors.” You can’t have a good press, he adds, “unless you’ve got good editors who are able to work together to develop an editorial program that makes sense both in intellectual terms and in commercial terms. Everything else kind of follows from that.”

Knowledgable observers give the Penn Press high marks for its acquiring editors. “The Press has had a terrific staff over the years,” says Peters. But there are only three acquiring editors now, which is why Halpern has found himself devoting a good deal of time to acquiring new books. (He’s been overseeing the Penn Greek Drama Series, a field in which he’s quite at home, having earned his master’s degree from Stanford in classical languages, a bachelor’s degree from Oxford in ancient history and philosophy, and another bachelor’s degree from the University of California at Santa Cruz in classical studies.)

It appears that all the Press’s departments are now functioning more as a team, with encouraging results. “We’ve become a lot better at promoting ourselves, promoting our image,” says Dr. Jerome Singerman, the humanities editor at the Press. “Our catalogue and ads are a lot more sophisticated than they were some years ago.”

“It’s very important for [all departments of] the Press to be publishing the same book,” says Halpern. “Before I came here, that decision-making really was a kind of non-collaborative process: the acquiring editors brought in books, but there was no input from any of the other departments in how we would publish it. So the editors thought they were publishing one book; the manuscript-editing department thought it was publishing another; same thing was true for design and production and marketing. Now we have decision-making meetings at which we’re all present and discuss what the Press wants in each case.”

Halpern also wants to ratchet up the involvement — financially and intellectually — of the Press’s board of trustees, and he has been revamping its faculty editorial board. “We want to make it a kind of blue-ribbon faculty panel, with the most prestigious faculty members represented,” he says. “It’s important to send a signal to the rest of the faculty that this is an important enterprise and that the most important members of the faculty are involved.”

This is no small undertaking. As Dr. Paul Korshin, professor of English and a former member of the editorial board, puts it: “The faculty at Penn has, for the most part, made publishing arrangements elsewhere.” The Press, he adds, “is not in a position to be aggressive” when it comes to recruiting new authors and books.

Korshin is among those who believe that the University — which has “always been chary of committing resources,” he says — needs to ratchet up its investment if the Press is to grow in both stature and size. In his view, it should get about $1 million a year in financial support from Penn, roughly five times what it is getting now.

Neither Dr. Stanley Chodorow, Penn’s provost through this past December, nor Dr. Michael Wachter, the interim provost, would comment on the Press or its financial needs. But the provost’s office has picked up the tab for the Press’s rent at 4200 Pine Street, so in effect, the Press did get a significant increase in its subvention.

“I really have no complaints about the University’s operating support,” says Halpern. “I knew coming in that it wasn’t going to be increased dramatically. The central administration is trying to cut about $25 million out of its budget. At many presses the operating support is going down. At this press it’s been lower than the norm for many years, so at least it won’t go any lower. But we do need to grow, and to do the kind of job that everyone wants, we need to get some source of revenue apart from sales income.”

Halpern’s main fundraising strategy is to build an endowment of $5 million. That would be more than 10 times the Press’s current endowment, and according to Halpern it would “make a really substantial” difference.

“Because we pay 80 percent of our bills through sales income, we can leverage that endowment pretty significantly,” he explains. “It will allow us to do things that we simply can’t do now — for instance, pay translators to translate books from other languages — and to take on some more ambitious, complex, heavily illustrated publication projects that would stretch our financial resources.” The Press has also been actively seeking grants for individual projects, snagging a major grant from the Getty Foundation and another from the Graham Foundation for its Penn Studies in Landscape Architecture series.

John Ryden, director of Yale University Press, says there is “no magic formula” for funding a university press, and indeed there are some presses that have flourished without any subvention at all. Cornell University Press grew substantially in the 1980s and is now one of the bigger and more successful presses in the country, despite receiving no money from Cornell University. While it makes a modest surplus by distributing books for other presses and through various fundraising procedures, on the whole, it pays its bills through sales of its books.

Can a press play in a league with the big guys, to use Tom Rotell’s phrase, without a big subvention?

“It’s hard,” Ackerman says candidly. “Very hard. But there are things that one can sometimes offer that the big guys can’t. More attention to individual titles, for example, and greater speed and more attention to editing. Sometimes having a press that’s more flexible is more important to an author than a big advance.

“Size shouldn’t be a criterion of excellence,” he concludes. “We could go around endlessly on what the right critical mass is, and if somebody has an answer to that, I’d love to hire them as a consultant.”

Yale’s John Ryden acknowledges that the bigger presses have “the economies of scale and the kind of support that long and deep backlists can provide. And it can take half a century to build them that way.” In a field where any book selling upwards of 10,000 copies is considered a best-seller — the Penn Press has about a dozen of those — only a handful of university presses are large enough to have the backlists and other resources to operate effectively without direct support from their universities.

But, Ryden adds: “The ‘big boys’ have no monopoly on quality, or any better ability to judge what scholarship will be of enduring significance. This is an art, not a science. And year in and year out, the small presses as well as the big presses do what we’re here to do — and what nobody else can or would do — and that’s publish scholarship in all its forms and do our best to keep it in print.”

In the final analysis, he says, “it is the list that defines the publisher. We are what we publish. Everything else is a means to that end.”