In this excerpt from his new book, Metropolitan Philadelphia, the author describes “the closest thing I have known to a peaceable kingdom.”

By Steven Conn | Photography by Jacques-Jean Tiziou

Sidebar | Famous for Being First … and Much More

The utopian impulse that shaped so much of American life in the 18th and 19th centuries subsided to a large extent in the first half of the 20th. It emerged again in the late 1960s and early 1970s as young people—and some not so young—tried to reimagine how life might be lived in the wake of the tumults of that era.

As was the case in previous centuries, this new effloresence of utopianism was largely a rural phenomenon. Small groups of people established alternative communities on old farmsteads in New England, especially in Massachusetts and Vermont, in California, and in a host of places in between. In those communes, they experimented with back-to-the-land communitarianism and with self-sufficient, organic agriculture, and they explored the relationship between the natural and the spiritual in ways that reached back at least as far as Henry David Thoreau. Except for the experiment that called itself the Movement for a New Society.

Beginning in 1970 a group of roughly 25 to 30 Quakers, peace activists, and civil rights veterans including Richard K. Taylor and Bill Moyer, both of whom had worked with Martin Luther King Jr., began meeting in Philadelphia to discuss what might come next both for the movement and for themselves. The Movement for a New Society was the result of those meetings and it was launched in 1971.

As George Lakey, one of the founders of the MNS, explains it, the movement grew out of a sense that despite a rhetoric of progressive social change, most of the activity associated with the 1960s was still mired in ‘‘old thinking,’’ especially when it came to the dynamics of gender, class, and race. Likewise, the energy of the 1960s consumed people at a great rate, burning them out and often leaving them damaged in the process. A primary goal for the MNS, then, was to create a community that would organize itself and live collectively, and that would provide a context in which participants could be sustained and nurtured in their political work. As George put it, with an equal mix of pride and exasperation: ‘‘Steve, it was hard, it was hard.’’

And the people who came together to begin the MNS made a self-conscious and deliberate choice that their experiment would be urban. As George acknowledges, those who went ‘‘back to the land’’ in the late 1960s and early 1970s were in some sense retreating. Most of the really difficult social issues facing the nation, from race relations to economic inequality to declining public education, are urban problems. Many of the New Left utopians, however, had made the City their enemy, along with the Establishment and the System. In this, they were little different from the hundreds of thousands of white city dwellers around the nation who left the city for their own version of bucolic paradise in the suburbs, except that they did so for slightly different reasons and went ever farther away. Indeed, as the decade of the 1960s came to a close, roughly 200,000 white Philadelphians had moved out to the surrounding suburbs to escape crime and violence, falling real estate values, and new black neighbors they could not abide. Almost 300 years after William Penn began his revolutionary urban utopia, those who committed to the MNS committed to stay in the city.

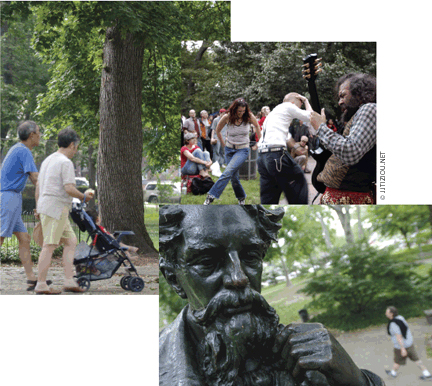

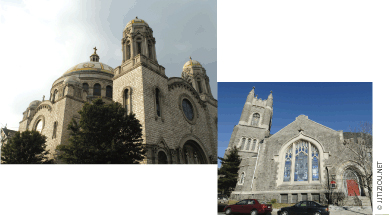

The Philadelphia neighborhood where they chose to plant their roots had become, by the early 1970s, no one’s idea of a peaceable kingdom. Located west of Penn’s campus and along Baltimore Avenue—the old colonial road—it had grown up in the late 19th century as a classic example of a ‘‘street car suburb.’’ Its large, elegant, late Victorian houses were home to prosperous Anglo-Protestants and Irish Catholics. The Catholics, in a show of their own ethno-religious pride, built the Church of St. Francis de Sales, a remarkable, vaguely Byzantine structure, whose bells still ring throughout the neighborhood and whose dome can be seen from points all over the city. Not to be outdone, the Methodists built the magnificent Calvary Church at 48th and Baltimore and topped their sanctuary with a breath-taking Tiffany glass dome. Residents of the neighborhood took their leisure at Clark Park, once the site of a Union hospital during the Civil War and now a leafy strolling park. And to underscore the bourgeois domesticity of it all, the neighbors erected a statue of Charles Dickens—the only one of him in the United States—with Little Nell at his feet in one corner of the park.

In the postwar years, that prosperity diminished somewhat. Many of the houses were subdivided into rental units and the population became more decidedly middle and working class. By the late 1960s, black residents began to move in from other surrounding neighborhoods. By 1971 the neighborhood seemed poised for the kind of collapse that had become so common in cities around the country. Crime became such a scourge that few people ventured out after dark, and many put bars up on their windows. Real estate agents went door to door goading white home owners to sell immediately—black people, after all, were moving in, and home values were only going to drop.

While the people who joined the MNS came with concerns about the big issues, the neighborhood itself became the first test case for their ideas. They began by addressing the problem of safety—organizing a system of block captains, neighborhood patrols, and neighborhood alerts. They helped calm the fears of at least some of those older residents who were poised to flee and persuaded many of them to stay. And they made sure that in all their efforts black and white residents worked together. The neighborhood stabilized. At a time when neighborhoods from the South Bronx to South Central Los Angeles descended into chaos largely because of racial tensions, the MNS created a model of how neighborhood transition did not have to mean neighborhood implosion.

The MNS was busy with other things as well, campaigns against the B-1 bomber and against nuclear power to name just two. But whatever the issue, as George explains, the 18 houses that collectively constituted the MNS Life Center served as the laboratory to try out new ideas about strategy, organizing, decision making, and so forth. ‘‘We were our own guinea pigs,’’ George remembers, and all these experiments were driven by the group’s maxim: ‘‘Most of what we need to know to be effective we have yet to learn.’’ The result was a profusion of creative ideas, some of which flopped, many of which were hugely successful. The 1970s and 1980s were, as George points out, disappointing times for Americans on the left. The promise of the 1960s proved, if not illusory, then at least a long way off. To sustain themselves, MNS members ‘‘set proximate goals for ourselves,’’ George explains, ‘‘so there was always some victory to celebrate.’’

The MNS hit the peak of its influence in the late 1970s, when roughly 300 people identified with it in cities such as Atlanta, Baltimore, Seattle, Toronto, and even in the tiny village of Yellow Springs, Ohio. Back in West Philadelphia, the MNS established New Society Publishers and a food co-op, which is still selling food on Baltimore Avenue.

The MNS was officially laid to rest in 1989, its remaining membership deciding that this particular experiment had run its course. There are still several group houses owned by the Life Center and they continue to provide a home and a haven for young people involved in community and political activism. George Lakey, too, still lives in the neighborhood and since 1992 he has run Training for Change. He travels around the world helping to build the capacity of activist groups to work for democratic change. He helped establish a network of activists in Russia in the tumultuous period after the Soviet Union collapsed and has been smuggled into Burma to train pro-democracy student groups there. The last time we spoke, George had just returned from Zimbabwe.

When I pointed out to him that he was merely exporting the utopian idealism of his West Philadelphia neighborhood around the world, he laughed and agreed. In 1982, a German television crew came to Philadelphia to mark the 300th anniversary of the founding of Philadelphia. German speakers, of course, constituted a major stream of migrants to Penn’s city; they came seeking religious freedom, and the television crew wanted to know what had become of the ‘‘holy experiment.’’ After talking with people at the Friends Center, they were sent to West Philadelphia. There, they were told, Penn’s dream was best being kept alive.

I should confess: this has been my neighborhood too, on and off for the last 15 years. It is a remarkably diverse, remarkably harmonious place. It still has a vibrant—indeed, sometimes exhausting—civic life, filled with community projects, political engagement, and festivals in Clark Park. It is where I have learned much of what I know about community and coexistence, about both the difficulties and the exhilarating possibilities of urban life. One of my neighbors (and my electrician, as it happens) has a bumper sticker that reads: ‘‘Heaven is a mixed neighborhood.’’ It may not be heaven, and it certainly is not immune to some of the city’s grinding problems, but it is still the closest thing I have known to a peaceable kingdom.

Reprinted with permission from Metropolitan Philadelphia: Living With the Presence of the Past by Steven Conn, copyright © 2006 by the Universityof Pennsylvania Press.

SIDEBAR

Famous for Being First … and Much More

Steven Conn’s roots in Philadelphia run deep. The son of Peter Conn, the Andrea Mitchell Professor of English, and Terry Conn, associate vice provost for University life, he grew up living in Hill House on Penn’s campus and then in nearby Narberth, Pennsylvania. But Conn Gr’94 says it wasn’t until after his undergraduate years at Yale University, when he returned to Philadelphia to earn his doctorate in history at Penn, that his relationship with the city truly developed on his own terms. “I studied it, walked around it, used it in my teaching, led tours of it, and participated in the community life of the West Philadelphia neighborhood I lived in,” he recalls. “I think it was during grad school that I started thinking about some of the things that wound up in this book.”

This book is Metropolitan Philadelphia: Living with the Presence of the Past, published in June by the University of Pennsylvania Press in its Metropolitan Portraits series. In an intimate, conversational style, Conn traces the city’s unique qualities, mixing personal anecdotes, arts and culture criticism, and consideration of broad economic forces to wrestle with the question of what it means to say, “I’m from Philadelphia.”

Conn’s other books include an anthology he coedited, Building the Nation: Americans Write About Their Architecture, Their Cities, and Their Landscape, also available from the Press, as well as Museums and American Intellectual Life, 1876-1926 and History’s Shadow: Native Americans and Historical Consciousness in the Nineteenth Century. In addition to his scholarly output, he also writes for The Philadelphia Inquirer, City Paper, and other newspapers.

Conn is associate professor of history and director of the public history program at Ohio State University, but he still maintains a home in West Philadelphia, where he planned to spend the summer. In between finishing up his spring semester work and getting ready to move, he answered a few questions about the book by e-mail.—J.P.

Why is the subtitle—“Living with the Presence of the Past”—especially true of Philadelphia?

I’m not sure I can answer “why,” but I do think Philadelphians live with their own ghosts more so than residents of any other metropolitan region. Certainly Henry James thought as much one hundred years ago when he toured the city. What I tried to explore in the book is the texture of the unique relationship between past and present that exists here.

We all grew up hearing about Ben Franklin and various Philadelphia “firsts.” Is that a mixed blessing?

I think to some extent it is. It reinforces the sense that Philadelphia’s best days are behind it, that it was all down hill after Ben died. I think that completely misunderstands the extraordinary history of this place in the 19th and 20th centuries, and it completely short-changes the region’s future.

There are also some firsts that are little known that you include—like a pre-Stonewall gay rights march at Independence Hall in 1965. Were there certain things like that you wanted to highlight?

I’m not sure I deliberately set out to highlight these lesser-known firsts but I was pleased as they began to accumulate in the book. I think what they underscore is that this town has a remarkable history of innovation—of all kinds—across its entire history. It doesn’t suffice to dismiss the region, as many residents and outsiders have, as conservative, stodgy, stagnant. It simply isn’t true and hasn’t really even been true, whether we’re talking about the birth of gay liberation here in the region in the 1950s, or the development of the first MRI machine at HUP.

Philadelphia seems to be in the midst of a renaissance. There are renovations and new condos and other new construction in and around Center City, lots of new restaurants and cultural centers. How do the city’s prospects look to you and what are some of the factors that will determine its future?

Historians have enough trouble dealing with the past—looking at the future is more than most of us can handle! But here goes: I think the region is positioned remarkably well to confront the 21st century, especially when we look at a knowledge economy, a bio-med economy, and an infrastructure which doesn’t have to be so dependent on oil. That’s the good news. Putting all the pieces together, however, will require a level of vision and leadership—political, civic, economic—which has not been in great supply around these parts over the years.

In fact, there are all kinds of innovators—and here we’re back to that topic—in the region: from people involved in wind-power generation, to pharmaceuticals, to small-scale urban agriculture. All kinds of exciting things going on.

But it is also the case that as the City goes, so goes the region. Plain and simple. And it is true that the City is really looking up in any number of ways right now. What this city needs to do—and all big cities are faced with this challenge—is attract and retain that broad middle class which has disappeared to the suburbs. This means fixing schools and neighborhoods and utilitarian services. Nothing as sexy as a new condo tower, but just as important for the future health of the city. Cities cannot survive as real and vital places if they are only home to the affluent and the poor. A Starbucks on every corner does not a healthy city make.