Benedicte Grima Santry spent years in the remote reaches of Afghanistan and Pakistan. What she learned—and now teaches—is invaluable, especially in the wake of 9/11.

By Beebe Bahrami

Benedicte Grima Santry Gr’89 sat in the back seat of a jeep in southeastern Afghanistan, wrapped in a floor-length, Iranian-style black chador. As she, her driver, and a paramedic bounced their way across the vast, desolate plain, always on the lookout for a blast of overhead gunfire, the driver suddenly whispered over his shoulder: “Saudis! Tighten your veil!” Grima Santry quickly stuffed all wisps of her dark hair under her veil and tightened her grip on the opaque fabric under her chin. The adrenaline surged.

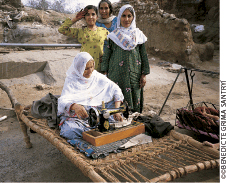

It was the holy month of Ramadan and the year was 1990. The three were working for Freedom Medicine inspecting rural medical clinics in the Logar and Wardak provinces south and east of Kabul. By then Grima Santry, a language and culture expert, had already been working for more than a decade among the tribal Pashtun peoples in whose territory they were traveling. Her fluency in Pashto and Farsi was a vital asset as she checked on the access of rural women and children to medical assistance, since outside men could not touch this issue. And because the clinics were often either run by men or located in male-oriented sections of a town, many women would rather risk their health than go to a clinic for treatment. Grima Santry’s findings would help local and foreign medical personnel give better care to the entire population.

It was a turbulent time in Afghanistan. The Soviets were pulling out after a decade of occupation, and the drive was extremely dangerous. Grima Santry and her companions had to cross empty stretches of plains in silence, often forming caravans with other cars: safety in numbers.

As the Soviets were withdrawing, Saudis were coming to help their fellow Muslims. Afghanistan and Pakistan are governed more by tradition and custom than anything else—including Islam, which is shaped by these cultural customs and traditions more than it shapes them. Visiting Gulf Arabs who had been unsuccessful at pushing their ultra-conservative Wahhabi interpretations of Islam back home found a receptive audience in the Pashtun-dominated territories of Afghanistan and Pakistan. In that fierce and isolationist region—where age-old patriarchal conservatism, a strict code of honor, and the Pashtun concept of hospitality hold sway—a new strain of Islamism took root.

As a result, Saudis were stationed at many of the checkpoints. At all of them, the three were asked: What are you doing? What’s your mission? Where are you going? For whom are you working? Throughout it all, Grima Santry would just sit there and not say a word; the driver and paramedic would speak for her.

At one particular checkpoint, the Saudi in charge nodded toward Grima Santry and asked if she was Engreeza, a term that once meant “English” but over the years had also come to more generically mean “foreigner.” The driver nodded yes, thinking of the generic meaning of the word. Wrong answer: the guard started yelling, Engreeza, Engreeza! Two days earlier the BBC had aired a report that had angered the Pashtuns. The guard confused the two meanings and thought Grima Santry was British.

The three were taken to the Saudi guard’s commander for more than two hours of interrogation. Who are you? Where did you go? Why do you speak Pashto? Where did you learn it? What are you doing here? Who are you talking to? Finally, the guards were convinced she was not a threat.

Asked if she ever felt threatened as a woman, Grima Santry calmly shakes her head. Her worry was because she was a foreigner.

Grima Santry is a rare American woman who has lived among Pashtuns for a long period of time. She has learned their way of life, made close friends, and excelled in their difficult language. Perhaps her most impressive feat is that, as a woman, she gained intimate knowledge of a people notorious for their isolation—and for severely restricting the movement and knowledge of their own women.

She first visited the region at the age of 18 in 1976, and later returned for what turned out to be more than a decade of living, studying, and working among Pashtuns, from 1978 to 1990. Hers is a 12-year tale of a woman traveling and living alone—or, sometimes, with her infant daughter—in the rugged reaches of Afghanistan and northwestern Pakistan. Such a feat is rare even among Pashtuns. For a Westerner, it is virtually unheard of.

It also requires complete fluency in Pashto. (In the scholarly world of Middle Eastern and Asian languages, there’s a common sentiment: Turkish, hard at first, then easy; Persian, easy at first, then hard. Pashto? Hard at first, then hard.) This Indo-Iranian language pulls in vocabulary from Urdu and Panjabi for Pakistani Pashtuns, whereas Pashtuns in Afghanistan sprinkle their language with vocabulary from Dari and Farsi, the Persian dialects of Afghanistan and Iran. When Grima Santry was first studying Pashto, it was such an obscure language for most Westerners that she had to resort to using a Russian-Pashto dictionary as her closest reference to a Western language. Studying Pashto already required reference to other dictionaries—Persian, Arabic, and Urdu—in order to locate etymologically linked words used in Pashto but not found in a Pashto dictionary.

Yet Pashto is one of the major languages of Afghanistan and the major regional language of Pakistan’s North West Frontier Province (NWFP), and the 17 million who do speak it comprise one of the main ethnic groups in both those countries. Among the Pashtuns are the Taliban and others who have given hospitality and protection to Osama Bin Laden and al-Qaeda members in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

In 1991, after two graduate students (Robert Nichols G’93 Gr’97 and Anne Carlin G’93) had requested to study Pashto, Grima Santry began teaching a class—made up of Nichols and Carlin. Though both went on to make significant contributions—Carlin with the World Bank in Washington and assisting refugees in Peshawar with the United Nations; Nichols as an associate professor of history at Stockton College in New Jersey who has published books and articles on South Asia—the program was dropped in 1993 because of the low enrollment. “The languages I studied were so obscure,” Grima Santry says now, “that I never thought there would be an interest in them.”

Then came 9/11. Penn’s Department of South Asia Studies contacted Grima Santry and asked her to return and teach Pashto. She now teaches three levels—beginning, intermediate, and advanced—to Penn students as well as to students from other institutions. Her courses expose her students to both the classical and modern written Pashto through classical poetry, historical texts, modern short stories, and folklore. She also prepares her students to understand the vast array of spoken Pashto, which has several dialects largely influenced by geography. For this, she uses materials recorded from her fieldwork, representing a variety of dialect regions.

Today Penn is one of only three institutions in the United States that offers Pashto studies (the other two are Indiana University and the Monterey Defense Language Institute). Grima Santry is among the world’s few experts on the culture, language, and history of the southwestern Asian region where Pashto is spoken. At the same time, the U.S. government desperately needs language and cultural experts to go to that part of the world.

“American foreign policy is handicapped by shortages of knowledge of foreign languages and cultures,” explains Dr. Brendan O’Leary, the Lauder Professor of Political Science and director of Penn’s Solomon Asch Center for Ethnopolitical Conflict. “The U.S. military plainly finds humanitarian intervention and peace-keeping more difficult because of the dearth of language education among its key personnel. Some would argue this absence disables their core-functions: war-making and counter-insurgency capacity.”

Dr. Whitney Azoy, senior research fellow at the American Institute of Afghanistan Studies in Kabul, agrees: “It’s a great pity—and a greater shame—that no U.S.-born American government officials have such command of this language, currently the most vital in our on-the-ground confrontation with militant Islam, and of others equally obscure.” Our national failing on that score “stands in stark contrast to 19th-century British colonial officials, who spent entire careers in one area of the Empire,” she adds, noting that because American diplomats continually relocate and often deal either with each other or with local elites who speak fluent English, they have to rely on translators with questionable loyalties and skills. “Witness the December 2001 debacle at Tora Bora: American troops in dubious alliance with local Pashto-speaking militias. How much got lost—or willfully distorted—in translation?”

Given Grima Santry’s “legendary” mastery of Pashto, Azoy suggests, “maybe Osama would not have escaped” had she been on hand.

While Grima Santry is modest about her proficiency in the language, those who have worked with her are often astounded. Birch Miles, a classmate of hers in William Hanaway’s 1979 Persian class and later a colleague in 1986-87 when both were in Pakistan, has vivid memories of Grima Santry’s linguistic capabilities.

“I would meet her in the morning to go out into the bazaar in Peshawar, that Dodge City at the east end of the Khyber Pass,” says Miles, who worked as a director and Persian-language interpreter at a medical clinic for Afghan refugees north of Peshawar, while Grima Santry was doing her fieldwork. “She would start out in the Peshawari dialect of Pashto, but if she detected a regional accent, she would change to that. Once, two merchants were so amazed at her ability that they turned to me and exclaimed, ‘She speaks Pashto better than we do!’ Then, in the afternoon, I’d pass by a refugee-aid agency that had a piano, and I could hear her singing Rossini and Mozart from over the walls.”

Thirty years ago, when her elderly aunt asked her to be her companion on a trip through Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, and Uzbekistan, Grima Santry seized the opportunity like a lifeline. Having grown up in a Foreign Service family, she was used to living and traveling around the world. Her American father was born in New York and shortly thereafter moved to France, where he grew up fluent in French. His ancestral family had come from the island of Gozo, Malta, the family name deriving from the Maltese Grimaldi. Grima Santry’s mother is from Versailles, France.

Until high school in Connecticut, Grima Santry grew up around the world in vastly different cultures: Algeria, the Philippines, Madagascar, and Switzerland. “If we were in a French-speaking country, we’d have to speak English in the house. And vice versa. In the U.S.A., we had to speak French at home. My parents maintained a completely bilingual atmosphere wherever we lived.”

By the time she was 18, she longed to immerse herself in the different cultures and languages that had defined her upbringing. Her aunt’s offer seemed heaven-sent.

Yet that trip also taunted her. As she helped her aging aunt get around on the tour she’d booked them on, Grima Santry yearned for the freedom to sit in the cafés and talk to the locals. Back in the States, she threw herself into gaining the skills that would allow her to go back on her own terms. She took up Persian studies at Bard College, where she was in her final year as a French comparative-literature and creative-writing major. After Bard, she went to Paris for two years of Farsi (Persian), Pashto, Urdu, and Arabic at the Institut des Langues Orientales.

In the summer of 1978, Grima Santry drove her Citroën “mini” from Paris, across Europe and into Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. She had two companions when she left Paris: The first she dropped off in the Turkish city of Konya; the other in Tehran. From there, she was on her own as she pushed eastward into more tribal, traditional, and remote territories.

Her first stop was Yazd in central Iran. It was to be an exploratory journey, to get a feel for the area from Iran to Pakistan. She stayed with an acquaintance in the Ministry of Culture who gave her tips on driving through the area: what speed to traverse certain tough roads, how to maximize the cool hours of the day, what archaeological ruins to seek out. He counseled her to wear a long black chador rather than the light pastel-colored ones popular in Iran at the time, and was so concerned about Grima Santry traveling to Mashad alone that he organized a caravan to get her there.

“I went to Mashad because I learned in Iran that they were now issuing visas to enter Afghanistan,” Grima Santry recalls. “This had not been the case when I had left Paris.” She then drove from Mashad to Herat, Kandahar, and on to Kabul.

Visas to Afghanistan in 1978 were only good for three weeks, so when that ran out Grima Santry went further east into Pakistan and Swat territory—both to renew her Afghan visa in Peshawar as well as to continue exploring the cultural landscapes that had captivated her—and the eastern stretches of Iran. Upon returning to Afghanistan, Grima Santry headed north, through Bamian, Baghlan, and Taloqan, near the Tajik border, openly using her tape recorder and notebook to document the everyday life of the people and to collect narratives.

It was a dangerous time to be in Afghanistan, which was falling more and more under Soviet influence. The local officials thought she was a spy.

“They arrested me and held me under ‘hotel arrest’ for three days until they transferred me to Kabul, where I was to be under house arrest for another 11 days,” recalls Grima Santry, whose car was at a campground across the street from the Ministry. “In Kabul, I convinced the officials to let me sleep in my car and spend the days at the Ministry of the Interior, where they could keep an eye on me. It was all very civil, but I was angry because I knew my arrest was because of the Soviets; it wasn’t the Afghans who were doing this to me. It was late November, 1978, and Soviet tanks were rolling through Kabul.”

For two weeks, a routine developed as the local officials decided what to do with this recalcitrant folklorist. Every morning, guards arrived at Grima Santry’s car to escort her across the street, where she would sit with four women who worked there, chatting, signing papers, filling out forms. At closing hours, she’d be escorted back to her car. The U.S. embassy did not intervene, though it did send someone every day to check on her welfare and to call her parents.

Finally, at the end of the two weeks, the Afghan officials gave her an ultimatum: Go, get out of here. She was having car problems and managed to convince them to give her 24 hours to get it fixed.

“The semester was beginning in Paris and I knew I would be late for classes, which began in November,” she recalls. “I returned via Iran, avoiding Tehran because I had heard there was unrest in the capital [foreshadowing the start of the Iranian Revolution]. I went along the side roads in the north, near the Caspian Sea. When I reached the border with Turkey, I didn’t want to cross alone, having been warned about that as a solo woman. So I waited with my car where Kurds guarded the border.”

The Kurdish tribesmen were very protective of her and would not let her cross the border with just anyone. At night, when a good crossing opportunity had not arrived, the men would take her to their homes to sleep with their womenfolk. It took three days before a trustworthy Swiss trucker the Kurds knew passed through; he let Grima Santry drive her car into the back of his freight truck and ride with him in the cab. They drove to Zürich together, and from there she rushed back to Paris in her Citröen to begin classes, which had started two weeks before.

The events of that summer had instilled a passion for the region in Grima Santry. By the end of her two years in Paris at the Institut des Langues Orientales, she had earned four language-certification degrees, one each in Persian, Pashto, Urdu, and Arabic.

While the French language system had a more intensive and holistic approach to teaching languages, there was nothing in France that compared to the doctoral studies in folklore at Penn, where there is a focus on oral narratives rather than just classical texts. In 1979 Grima Santry enrolled in Penn’s folklore department, and 10 years later—after making several extended stays in the NWFP and one trip into Afghanistan —she received her Ph.D.

Studying Pashto oral and folk literature, Grima Santry began formulating her own research interest: how Pashtun women express emotions, especially in such a controlling, segregated society. All previous scholarship on the Pashtuns dealt only with men’s experience. Both her books—The Performance of Emotion Among Paxtun Women and Secrets from the Field—are intimate accounts of Pashtun society and especially of women’s stories and experience. Where The Performance of Emotion is an academic study, Secrets is intended for a general readership and offers a first-hand account of life among the Pashtuns.

One of the key concepts for anyone living and working among Pashtuns is pashtunwali. In Secrets, Grima Santry elaborates: “Pashtunwali is language, culture, and law bound into a tight recipe for life and self-pride. It is the root belief that drives Pashtuns in everyday actions and decisions. Although Muslim, Pashtuns experience the clash between pashtunwali and Islam on a number of issues. Pashto takes precedence in these instances, although they do not consider themselves any less Muslim for it.”

Pashtunwali is at the core of the Pashtuns’ way of life—specifying and controlling men’s and women’s honor and shame, behavior and hopes—and it reveals the workings of one of the world’s most socially conservative people. While pashtunwali might seem rigid and unchanging, its very strength has given the Pashtuns a means to survive in their rugged physical and social terrain.

It also offers control in extreme circumstances, in a land where violent upheaval is the norm. After a decade of precarious power in Kabul, for example, the Soviet-backed government collapsed, and the resulting power vacuum left Afghanistan open to competing warlords, whose popularity was greatly enhanced by their resistance to the foreign occupiers. In 1996, the Pashtun Taliban gained the upper hand, promising order in exchange for adherence to a more conservative cultural code based in pashtunwali.

But even among Pashtuns, the Saudis who had come to live among them seemed more religiously conservative. They encouraged some of the same stringent behavior as Pashtuns, and provided immediate support, and voice, for the Pashtun Taliban, which took an existing law and felt empowered to impose it on the rest of the country. Yet even though the Pashtuns comprise the largest group (42 percent) in Afghanistan (which also hosts Tajiks, Hazaras, Uzbeks, Aimaks, Turkmen, Baluch, and smaller numbers of other groups), they are not a majority. Support for their policies was less than rock-solid.

Still, what drew Grima Santry to this rugged, difficult region was always the people, especially their “conversations, attitudes, and openness.”

“It was also about the impression that they were so different [from my culture] and I felt very comfortable there,” she adds. “I was also always piqued by something that I felt was being withheld; that also made being there very intriguing.”

Of course, she is much stronger than she lets on. When preparing for her role as Mimi in a production of La Bohème, she lifted weights to strengthen her ability to belt out her final, dying aria while lying on her back. And when traveling alone in the NWFP she positioned—and used—a sharp knife hidden under her veil, ready to jab at any inappropriately groping hands on buses and in crowds. And yet, she says: “I also felt protected. I never felt threatened or unsafe. I felt there was always someone there to help me get what needed to be done. And while my status shifted the more proficient I became at reading the culture, it was my effort to read it in the first place, to understand, that gave me respect, that invited people to help me.”

It was this shifting status, from novice to expert, that defined her many years among Pashtuns. “Early on, when I was just learning, I could arrive at a place and sit with the men. It was okay. But later, as I was known and knew the cultural rules better, sitting with the men became taboo. As soon as I arrived at a home, I had to go right to where the women were gathered.”

Asked if it was difficult to be a woman in the NWFP, Grima Santry shrugs and tells a story about an Iranian man she had met who had arrived in Peshawar on a Fulbright scholarship to study at the university: “He was excluded from family life; he had no social life; and he was always on trial as a Muslim man. After a few months, he left.”

As a female outsider, Grima Santra was less of a threat; she would not endanger a family’s honor the way an outsider male could. And yet as an outsider, and a culturally aware one at that, she was often sought out by both men and women, who would tell her their worries. This was especially poignant for a folklorist who was there to understand women’s emotional lives, a theme she says was practically dictated to her.

Grima Santry’s original impetus was to study the popular storytelling genres of the time, ones she had been exposed to through chapbooks and cassettes. But as she inquired into popular oral tales, people directed her to their women kin.

“The more I asked about [storytelling], the more people said, ‘Oh, go see my grandmother. Go see my mother. Go sit with them, they know all about it,’” she relates. “So I became more sensitive to what was important in their world, and that was visits—that was what life centered around. And visits were centered around emotions.”

It was not acceptable for a woman to complain about her husband. What was acceptable to talk about was personal loss. And storytelling was the best way to express loss. It was a part of a woman’s catharsis, to tell a complete tale, one where she is the protagonist; to offer a beginning, middle, and end; and have it as a vehicle for other women to comment and sigh over.

It’s a balmy, Indian Summer day in suburban Philadelphia. A nearby fire department sounds its siren as Grima Santry sits near the vegetable garden she and her family have planted in their backyard, talking about the possibilities of a life in Kabul.

Given the scarcity of specialists in Pashto and Urdu and Arabic and Persian, it’s not surprising to learn that private consulting companies that recruit for the government have approached Grima Santry with lucrative offers to work out of Kabul. She has seriously considered them, but to relocate her family has tough issues attached. First and foremost is safety. Then there is the matter of schools for her children and the question of what her husband would do.

Her son, the younger of her two children, was quite excited by the prospect. “When he learned that the Afghan diet is mostly grilled meats and not many vegetables,” she recalls, “he said, ‘Oh, that’s great!’ He was thrilled.” But even he was only interested in going for a summer, not a school year. Her daughter, older and on the edge of a promising athletic career as a runner and swimmer, was concerned enough to write her mother a letter detailing her misgivings.

Were she by herself, Grima Santry would go. After all, “I probably shouldn’t have gone into Afghanistan in 1990.”

But in the end, safety issues and the potential for disrupting the whole family outweighed the amazing international experience and professional satisfaction such a position could offer. Though she hopes one day to return and see how the people are and how things have changed, for now, Grima Santry’s passion is channeled into conveying the linguistic and cultural issues to the next generation, ones so desperately needed by anyone venturing into the far-reaching issues concerning Afghanistan.

“My interest now is limited to keeping the Pashto program vibrant, encouraging students to apply their language and culture skills to broadening research or diplomatic ties,” she says. “As our administration pours increasing funds into learning critical languages, it’s equally important to increase the understanding of cultures, and to encourage more researchers to get involved.

“Afghanistan is currently slipping quietly back into chaos, which is what allowed the Taliban to surface in the first place,” she adds. “Why the chaos, and who emerges at such times? That answer lies in the currently existing situation of people in their everyday lives. And hence the value in understanding those lives.”

Beebe Bahrami Gr’95 is a freelance writer and cultural anthropologist who writes for the Gazette, Archaeology magazine, Expedition magazine, and other publications.