A movie producer and Class of ’68 alumnus recalls the cinematic passions of his senior year—and offers some advice on rekindling the romance for today’s audiences.

BY ROBERT CORT | Illustration by Jonathan Bartlett

My crush on movies began on a damp November night in 1956. Dressed in my first suit—itchy and gray—I sat in the backseat of our Oldsmobile as my parents crossed the Brooklyn Bridge into Manhattan. At Mama Leone’s I tasted Parmesan cheese for the first time. Then we walked a few blocks to the only theater in the world playing the widescreen epic comedy-adventure, Around the World in 80 Days.

I was already a regular at Saturday matinees, more for the popcorn fights than the ‘B’ westerns. But my life changed when we arrived in Times Square. The Rivoli Theater had eight marble arches above the marquee; 2,000 seats in the orchestra, mezzanine and balcony; a domed ceiling 10 stories high, and a huge curved screen. I felt dwarfed by my surroundings and infinitely important at the same time.

Around the World was a grand spectacle that ultimately claimed the Academy Award for Best Picture. Beyond its exotic locales, it was my first experience of characters attempting the impossible. When David Niven as Phineas Fogg realized that crossing the International Date Line had returned him to London on Day 80, the communal exuberance was thrilling.

A year later my brother took me to another palace, the Capitol Theater, for The Bridge on the River Kwai. World War II had ended only 12 years earlier, but it was already a war that had happened to other people. Then David Lean’s movie slammed me in the gut. At 11 I began to comprehend what war’s madness does to men, and what individual heroism means. Kwai remains my favorite movie of all time.

In 1958 Gigi completed the trifecta. Leslie Caron played teenage Gigi. I stole her poster. But what struck me most was Louis Jourdan as Gaston realizing how much he loved Gigi and pursuing her through Paris singing, “Gigi, what miracle has made you the way you are?” Before that scene, what I’d observed about men and women in love was my parents’ marriage, and that didn’t seem something to pine for.

Three Best Pictures, three years in a row: the thrill of daring men in the wide, wide, Todd-AO world; the horrors that could overwhelm it; the promise it held of exquisite feelings. Though the films others embraced might differ, millions of boomers had also fallen for the movie-going experience.

Planning for my 50th reunion this past May [“Alumni Weekend,” this issue] focused me on the deep disparity in film between my senior year and now. To the Class of ’68, “Want to see a movie?” was as popular a question as, “Want to get a drink?” We’d stand in lines around the block to see the latest releases. Those lines were badges of honor, bonding us, increasing our anticipation. The next day we’d discuss and dissect. Film’s mystique was potent and its future promising. So much so that I cast off a career and life in the East, moved to Hollywood, and became a producer.

Today admissions to movie theaters are stagnant, the core audience is indifferent, and movie studios are consolidating. In Hollywood, film has lost its standing atop the entertainment pyramid. Movies no longer set the cultural conversation. Worst of all, my wife and I can’t find a film we want to see on the weekend.

For me, this downshift isn’t, to paraphrase The Godfather, just business—it’s personal.

FADE IN:

Our story begins in the fall of 1967 when we returned for senior year. Rage and anxiety sparked—ignited by the Vietnam War. As the death toll mounted, boomers increasingly saw the war as immoral. When I realized I might have to risk my life to fight in it, I joined the active opposition. The urgent civil rights movement, burgeoning feminism, and mind-bending drugs magnified the uproar. Virulent protests played to the soundtrack of insurgent rock music.

Divides cross-hatched the nation: a generation gap in which we couldn’t trust anyone over 30 and they considered us radical hippies; between middle class youth scheming a way out of military service and working-class kids marching into it; between young women embracing careers and their moms who saw raising families as the purpose of their lives; between rebels on the barricades and the law-and-order faithful. Whoever you were, you saw danger in the road ahead.

Rather than run for the hills (or Canada) we first-wave boomers took this uncertainty as a challenge and decided to re-make the world in our image. It was time for revolution. The transformative movies that arrived in the fall of 1967 and into 1968 certified our feelings. Fueled their fire. Drove them to new heights.

On the first day of classes, must-see word-of-mouth was already spreading about two movies—Bonnie and Clyde and In the Heat of the Night—that promised to break the mold of 1960s films. Even the best of that lot, from Doctor Zhivago to The Sound of Music, reflected the gestalt and style of a 1950s America disappearing in the rear-view mirror. Hollywood had lost its way.

I saw the Steiger-Poitier film and felt a hot surge I’d been missing. The murder of civil rights workers in Mississippi in 1964 had made the South hostile ground. My gut tightened for Poitier’s brilliant detective, Virgil Tibbs, when he’s co-opted to help Rod Steiger’s arrogant-ignorant sheriff solve a murder in a redneck town. Steiger was every adult who waved the flag for the war and ridiculed my long hair. But these men’s edgy alliance suggested hope, however slim, of a way forward. Certainly not a pat ending, but an unexpectedly satisfying one.

Such equivocal curtains would mark the best of film during the next tumultuous 12 months. It was as if movies were saying, “Look, no bullshit—you’re in a fight to the finish. So what if the fight wasn’t of your making. You can’t give up until the system changes. We’re outlaws. So, fuck it.” I found the message terrifying, but sitting in that audience, I knew I had company. Just like a crack army unit, we were fighting as much for our brothers and sisters as for our ideas.

Bonnie and Clyde aimed at our groin—an explosive, brash, sexy backseat ride. Stars Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway were a young, hot, hopelessly blind couple daring to take down the heart of institutional America—its banks. The movie appalled establishment critics like 62-year-old Bosley Crowther in The New York Times: “A cheap piece of bald-faced slapstick comedy that treats the hideous depredations of that sleazy, moronic pair as though they were as full of fun and frolic as the jazz-age cutups.” And thrilled younger ones like 25-year-old Roger Ebert: “A milestone in the history of American movies, a work of truth and brilliance.” Pravda denounced it; Norway banned it; everyone in the theater the night I saw it cheered—even when our brother and sister died in a riddle of Tommy-gun fire. We were indeed outlaws.

Cool Hand Luke arrived after fall midterms. The opening scene of Paul Newman decapitating parking meters announced: “Stick it to the man.” His confrontations with Strother Martin’s warden and George Kennedy’s king of the convicts marked him as the ultimate rebel. With escape after escape, beating after beating, hard-boiled egg after hard-boiled egg, Luke captured us.

Two diametrically opposite films—both groundbreaking—arrived just after Thanksgiving. In Cold Blood, based on Truman Capote’s best-selling book, created the genre of true crime drama, chronicling the grisly murders of a Kansas family. The film revealed the two itinerant criminals as senseless, brutal, and remorseless. It was a reminder that the savage images from Vietnam had a domestic counterpart.

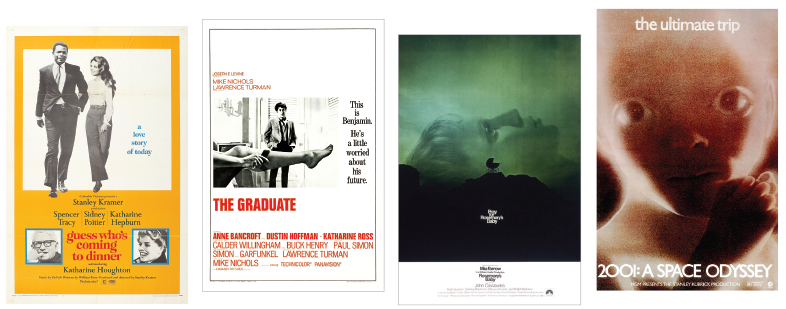

In contrast, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner gave us Sidney Poitier marrying the daughter of Spencer Tracy and Katherine Hepburn—over the old man’s objections. Again, the establishment fell—it was what America wanted to believe could be happily ever after. I borrowed from it in making Save the Last Dance 30 years later. The two remain the top box office successes among interracial love stories.

Our Christmas present was perhaps the finest serio-comedic movie of all time, The Graduate. Benjamin Braddock was us. We felt his alienation from the corrupt adult world. When he’s seduced by Mrs. Robinson, he’s able to shake off her octopus grip and crash even the sanctity of the church to recruit her daughter Elaine to an unknown future, but one that belonged to them. Again, the movie delivered an infamously ambiguous ending, but one that sent us into the night in a state of euphoria.

It didn’t last. In February Lyndon Johnson dropped the guillotine when he ended graduate school deferments. We all became potential canon-fodder. What should have been a glorious “senior slump” became a rush to find a way out. I even tried joining the Coast Guard, until I learned it required a long swim in icy waters. Parents, friends, and advisors pitched in. But most of us paid a price.

Rosemary’s Baby arrived during my rat-in-the-maze spring. It was a portrait of paranoia. Except Mia Farrow’s Rosemary wasn’t just imagining, she saw the evil in Ruth Gordon’s grotesque neighbor, Ralph Bellamy’s obstetrician, and her desperate actor-husband. The film’s foreboding pays off with the awful certainty of no way out.

As do the final frames of 2001: A Space Odyssey, which premiered on April 2, 1968. Director Stanley Kubrick broke from any previous Buck Rogers version of space. When Hal the computer takes control, we’re hit with the morbid impotence that would permeate a society rocked by the assassinations of Dr. King two days later and Bobby Kennedy that June.

As 2001 foreshadowed the eventual popularity of space-based science-fiction, Planet of the Apes (release date March 27) did the same for dystopian visions of earth after the apocalypse. When Charlton Heston saw the toppled head of the Statue of Liberty, even a pseudo-sophisticate like me gasped.

These remarkable movies released during our final two semesters at Penn garnered 50 Academy Award nominations. They represent a creative achievement that the movie business hadn’t seen since 1939, whenGone with the Wind competed with The Wizard of Oz,Wuthering Heights, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Ninotchka, and Stagecoach. Despite differences in genre and subject, they were proudly subversive. Characters saw the darkening shadows; they boldly challenged the power structure, confronting rather than escaping conflicts. Our heroes and anti-heroes didn’t always win—they were often bludgeoned and bloody—but they were alive with the fight.

The transition to movies aimed at the boomer generation was messy, not discrete. Camelot and Dr. Doolittle were also released in our senior year. But the executives in Hollywood quickly realized how profoundly we’d changed the movie marketplace.

Television—still with only three major channels—had a huge nightly audience for the likes of The Andy Griffith Show, Gomer Pyle, USMC , Gunsmoke, and Family Affair. Nobody I knew bothered to watch. Film was our medium. Our cohort would dominate society with our dreams and demands. And we’d turn the movie business back into the bonanza it had been in the Golden Age of the 1930s and 1940s.

CUT TO:

The present. My female classmates have reached professional heights that seemed out of reach at graduation. Gays, rarely out of the closet in 1968, can now marry. A white country has grown diverse. The knowledge we were once required to go forth and seek now resides at our fingertips. Conversely, the once comfortable middle class is no longer. It’s still dangerous to be a black man. And baby boomers, who thought they’d remain forever young, face their delusion getting out of bed in the morning.

But a profound similarity to my senior year is that we’re a sharply divided society. Those partisan rifts are different but equally deep: between the 1 percent and the 99; between city-dwellers with their eyes on the prize and disrespected Americans in moribund towns; between immigrants and nationalists. Everyone’s hurling blame at someone else. We have a president as paranoid as Richard Nixon. Distrust of institutions now extends beyond government to business, law, religion, medicine, and sports. The Cold War is long over, but Russia continues as a malevolent foe. Today’s college seniors don’t fear a military draft, but they’re anxious as hell about their futures.

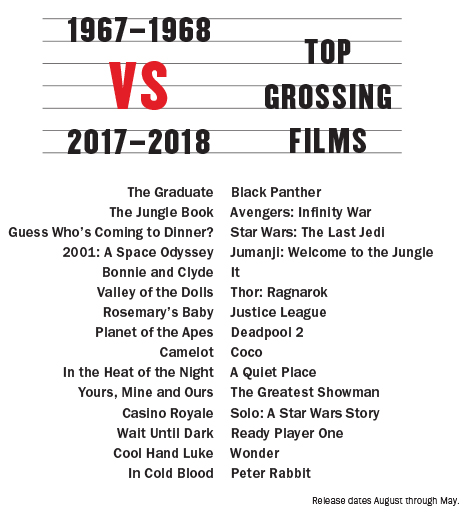

As a producer, this landscape suggests an abundance of movie ideas. But when I go to make them, I often encounter no takers. To demonstrate, I created a chart (above) that compares the 15 top-grossing films released between August and May of my senior year and that of the Class of 2018.

It’s stunning today to see that the provocative films from 50 years ago were not only artistic triumphs; they also achieved vast commercial success. All of them were top box office hits. Examining, inhabiting, and personifying the fractured world in the late 1960s captured the audience.

But the top hits this past year feel like they’re from another world—literally. Rather than confront reality, Hollywood has adopted a new approach: ignore it. Studio movies now live in fantasy. Eighty percent of this year’s hits are grand scale comic book, fantasy, science fiction, and animation. Compare that to 20 percent in ’67–’68. This pattern is intensifying. Of the top box office hits for the last 10 years, 70 percent are fantasy-based, compared to roughly 10 percent from the 1950s to the 1980s. Fantasy is the sandbox in which studios want to play. Some of these films, like Black Panther, embody complex themes and are additions to cinema’s pantheon. But most are as disposable as diapers.

Originality was once prized in Hollywood; now it’s a dirty word. More than half of the top 15 this past year are sequels and reboots. Only Casino Royale and Jungle Book in ’67–’68 fit that bill. Pre-sold titles are preferred to fresh ideas. That’s because current production costs dwarf the inflation-adjusted budgets from 50 years ago. And today’s marketing costs can run 50 times what they were in the 1960s. Sequels and remakes, I’m regularly reminded, are favored because they already have “brand awareness.” This is not a term I ever heard applied to movies in my senior year. Or even during my first decades as a producer. Movies, it seems, have become just another commodity, marketing is now the godhead of the film business.

So when producers like me aspire to make the likes of In the Heat of the Night and The Graduate—confronting intricacies of people and relationships—what we hear from studio executives is: “Dramas won’t work overseas. Foreign moviegoers want big and simple; they want explosions; they want American movies that aren’t really about America.” That’s also critical to the studios because 72 percent of their revenue flows from the international market. It’s a complete flip from the last century, when studios earned 75 percent from the domestic market. Hollywood used to export its movies; now it makes movies for export.

I counter that the movies I’m proposing cost so much less, we don’t need as much from foreign markets to have a hit. Their answer is that such movies won’t even work domestically. There’s just too much competition for our entertainment time: 500 channels of television, instant streaming, double the number of professional sports franchises from 50 years ago, video games, and the internet with all its infinite distractions.

When my conversation with the studio ends (or now rarely begins), I seek independent financing. This is a process akin to door-to-door sales in a cold weather climate. The equity is tough to raise, so by default the scope of the stories producers can tell is limited. But even in success, one faces another hurdle. Such films are generally released through small distribution companies with meager marketing budgets. Even the best rarely earn as much in total as a big studio film does on its opening Friday night. Most simply wind up on indecipherable video-on-demand (VOD) menus. The dramas, comedies, and thrillers that cut to our core and roused us are a near extinct species.

If the strategy adopted by the studios only frustrated boomers like me, it might be understandable, albeit disappointing. But despite being targeted by Hollywood, our children and grandchildren have never developed a passion for film. Among 18- to 24-year-olds, admissions have declined 17 percent since 2012. Movies are casual hookups—as if the youth know deep down that most of the extravaganzas are fun but won’t last a lifetime in their memories. It remains an open question whether millennials and the “iGen” cohort behind them have an appetite for challenging films. Tastes of audiences change, as was proven in the seismic shift in my senior year. It’s possible that edgy films, in the mode of the memorable movies of ’67–’68, would discomfort rather than galvanize. That today’s self-protective younger audience would prefer to turn their heads. And that they get a bigger charge out of virtual reality than a century-old technology.

We don’t have an answer because so few movies as good and commercial as Bonnie and Clyde and Cool Hand Luke get made. That’s my prescription for saving our relationship to film. Rekindle the romance by encouraging talented filmmakers to make movies about the real world, instead of seducing them with millions to make Fantasy #5. Support those movies with aggressive marketing. This requires a commitment by the studios. My bet is that if they make it, the movies will resonate with the audiences that determine the future of film. Like embracing clean energy, rebuilding Hollywood’s legacy is not only the right thing to do, it will prove the profitable one as well.

The best evidence for this is the boom in television, where everyone from teens to boomers now go for their emotional fix. Some of what used to be those classic movie experiences can still be enjoyed on cable. But even television is increasingly infused with fantasy and remakes. And the medium has become so atomized that each of the hundreds of programs garner tiny, niche audiences. It’s a rare show like Game of Thrones that unites a broad swath of America around a single viewing experience.

Movies can accomplish that because they are a unique form of storytelling. I love their elegant completeness in two hours. It stands in contrast to the buy-in required with television series that continue season after season. When seen and savored in the dark in a communal setting, films possess vast power to convey truth and emotion. When they capture the public imagination, they are still what we talk about the next day and for weeks to come. They can affect us, thrill us, inspire us, unite us, and alter our perceptions of our society in a way that no other medium can.

Which is why, despite the slings and arrows, I’m still producing.

Robert Cort C’68 G’70 WG’74 has produced dozens of films since the 1980s that have grossed in excess of $3 billion. His latest, On the Basis of Sex, about Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s landmark first case as a lawyer, is scheduled for release on November 9, 2018.

Can anyone remember the name of the professor and course that was taught in the early-mid 70s that I think was titled “Social History Through Movies” where the first semester focused on silent films and the 2nd talkies. We watched a movie at 4:00 virtually every day. I was a TA my junior year. If anyone has any information and a syllabus they could email me I would be grateful.

Maurice Pogoda C ’77

Thank you for a well-written, passionate look at the past, present and future of producing movies, and how you keep fighting to make movies that matter, and at least break even. Although I agree with your take on the current state of cinema, I remind myself that the shimmering, groundbreaking “Moonlight” can win the Oscar and last year’s list of best films from the American Film Institute and the Academy Award nominees give us hope. And it that doesn’t do it, then we still might have a few good films left in us, now that the trifecta of plutocracy, oligarchy and fascism threatens to strangle our democracy, and high school kids are marching in the streets, not to protest a war but to protest being shot or killed from the bullets of their own citizens.

During my undergraduate years at Penn from ‘66 to ‘70 what resonated most was the line, “Want to see a movie?”, which reflected our cultural and counter-cultural sentiments. I also want to pay tribute to three more forces in and around the University that drove my love for movies. First, thanks to the student film society, where we could catch a classic or foreign film, expanding our vision of what this art was could be, be it Casablanca or Bergman’s Smiles of a Summer night. Second, when on-campus films weren’t enough, I would take the subway to the suburbs to the Band Box, Philly’s only repertory movie theater. Third, between classes, I would make a weekly pilgrimage to the Annenburg Center Library where I read the latest issues of Film Comment and Cahiers de Cinema. But most important was the long-form review in the New Republic from America’s most brilliant and provocative film critic Pauline Kael. If I were teaching the next generation of filmmakers, after presenting an old film, be it good-bad, success-failure, or in between, I would make them discuss her review, then let the discussion rip about what really matters in making movies.

P.S. After seeing the wonderful RBG in a packed movie theater, my wife and I are looking forward to your superbly casted film. Talk about inspiring the next generation of women, including my granddaughters.

If you went to Penn in the ’60’s, you must remember the Spruce Theatre at 60th & Spruce., one of the in Philly to show foreign films.