One of landscape architecture’s most eloquent urbanists gets the documentary treatment.

“This film is Gina’s art,” observed Laurie Olin, standing amidst a crowd gathered at Weitzman School of Design’s Meyerson Hall for a premiere of Sitting Still, a new documentary from Gina M. Angelone. “It’s her editing and her vision that leaves you with this product, not some other one.”

As the film unfolded a few minutes later, though, it became clear that the star of the show was indeed Olin, the National Medal of Arts–winning landscape architect and School of Design emeritus professor whose noteworthy projects with OLIN, the firm he cofounded in 1976, include Battery Park City in New York, the Washington Monument grounds in Washington, DC, and Denver’s 16th Street pedestrian mall.

For the first third of the film, Olin’s voice is the only one we hear as he spins a lyrical tale of his boyhood arrival in Alaska upon his family’s relocation there. There were Eskimos, he says, and white-bearded prospectors brandishing gold nuggets. There were waffles! “It was so cool!” he grins. “It was a boy’s paradise.” This was 1946 and the eight-year-old grew fascinated by something else, too. “Look down the street, and there was nature,” he marvels. “There was no separation.”

As Olin speaks, images of his finely detailed drawings and delicate watercolors from that era flit across the screen. The frontier is what first compelled him to start keeping a sketchbook, he says, and he’s never stopped. “I’m so in love with the world and the pleasure it gives me, that I just keep trying to put it down.”

Based in Philadelphia, the award–winning Angelone was introduced to Olin in 2012 when the Cultural Landscape Foundation commissioned her to shoot a series of oral histories on pioneers of landscape architecture. “What came across immediately was Laurie’s brilliance and charisma,” she reflected a few days after the premiere. “Plus, he had such a fantastic memory, down to the most minute details. It all added up to evidence of his commitment to paying attention, which is one of the things we wanted to explore in the film.”

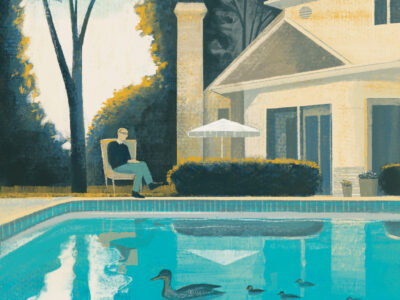

Her project would take nearly 10 years, derailed by fundraising challenges and the pandemic. Primarily shot in 2016, the documentary often positions Olin—wearing a black sweater, black pants, and a collared white shirt—behind a white desk in the middle of a soundstage with a gleaming white floor. A white cyclorama serves as a backdrop, suggestive of an art studio. As he muses on his early days and inspirations, Angelone intersperses B-roll shots of meaningful places in his life (including, briefly, some of his best-known projects), stock footage of crashing waves and hurricanes, archival and vintage photos, and, always, his drawings and paintings. “One of the joys of landscape architecture is to walk out onto a site and look at it and say, ‘Ah, I remember when I did that first little sketch and—there it is,’” he observes.

With the same elusive quality that suffuses Olin’s drawings of Rome’s Trevi Fountain or Central Park’s Belvedere Castle, the film alights on his professional trajectory here and there. The fuller portrait that emerges, though, is that of a keen observer, nature-lover, and devout urbanist. “That was a deliberate choice,” said Angelone. “I struggled with not going into his wonderful awards and the poetic way he talks about his projects. But that’s all out there—just Google it.” [“Mr. Olin’s Neighborhood,” Jan|Feb 2007.]

Eventually, a procession of stellar talking heads enters the picture. This gang includes starchitect Frank Gehry; architect Billie Tsien, who partnered with him on Philadelphia’s Barnes Foundation; Walter Hood, one of today’s preeminent landscape architects; and Penn’s David Brownlee, the Frances Shapiro-Weitzenhoffer Professor Emeritus of 19th Century European Art and a historian of modern architecture.

They come first to praise Olin (“The humanity of whoever Laurie Olin is inside comes out in those drawings,” says Gehry), then reappear in the final third of the film to expound, along with Olin himself, on a litany of urban and societal woes that include affordable housing, climate change, digital hegemony, gentrification, and sustainability. “They’re talking about all of the social concerns that have driven Laurie’s work through his career,” Angelone said. “I wanted to immerse the audience in the things he cares about.”

That a landscape architect would have thoughts on these problems probably won’t surprise many viewers. The real eye-opener here is the sheer volume and tremendous variety of Olin’s thousands of illustrations. They, more than anything, seem to speak to his personality, his life, and his legacy. “You learn more and you savor more if you move a little slower. And drawing really slows you down,” he says at one point. “There is a sense I get when I do a drawing that I was there, I was alive, there was that moment.”

—JoAnn Greco

For information about screenings, visit sittingstillmovie.com.