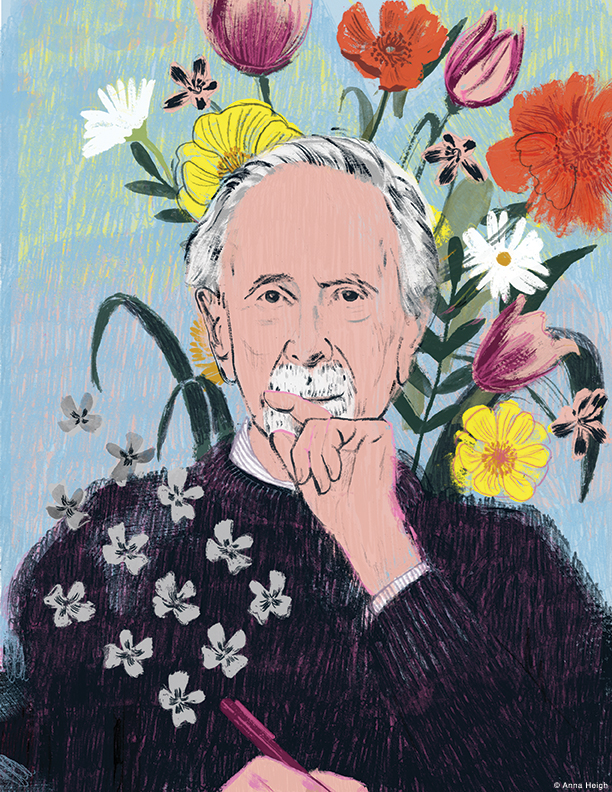

In the year of his centenary, a look back at the music and thought of American composer and Penn faculty member George Rochberg G’49, who first embraced 12-tone music and serialism and later rejected avant-garde styles as a form of “self-extinction.”

BY DENNIS DRABELLE | Illustration by Anna Heigh

A high point in the life of George Rochberg G’49 came in the spring of 1961, when he and his wife were in New York to hear the Cleveland Orchestra, conducted by George Szell, play his Second Symphony in Carnegie Hall. After the performance, the Rochbergs went somewhere for a bite to eat. “As we were being shown to a table,” the composer recalled in his posthumous memoir, Five Lines, Four Spaces: The World of My Music [“Arts,” Sept|Oct 2009], “we were greeted by a chorus of men’s voices giving forth in lusty unison—and all the right pitches, too—the opening three clipped phrases of my Second Symphony! I couldn’t believe my ears.” Making up the impromptu chorus, he realized, were Cleveland Orchestra members who had chosen the same restaurant for their post-concert meal.

Rochberg, who died in 2005, would have turned 100 in July of this year. A Penn faculty member for almost a quarter-century, he had been hired to treat an ailing music department that was, in his words, “desperately in need of radical surgery if it was to survive at all.” After operating successfully, he stepped down as departmental chair but stayed on to teach. By his own admission, his academic career was a matter of necessity—composing symphonies, concertos, and string quartets is hardly a lucrative pursuit. Yet for someone who thought and wrote trenchantly about the state of classical music and his own rebellion against the reigning orthodoxy, academe wasn’t a bad fit. Rochberg liked to philosophize but also hankered for the kind of acclaim he got from those charming Clevelanders.

The son of Ukrainian Jewish immigrants, Rochberg was born in Paterson, New Jersey, and raised in Passaic. He helped put himself through Montclair State Teachers College (now Montclair State University) by playing piano in jazz bands, an experience that nurtured his flair for improvisation. He fell in love with a fellow student, Gene Rosenfeld, whom he married in 1941. By then he was studying music at the Mannes School in New York, where Szell was one of his teachers. Later Rochberg studied at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia.

He was drafted into the Army during World War II. Serving as an infantry officer, he was wounded in battle and won a Purple Heart. Back in the States, he enrolled at Penn, earning a master’s degree in 1949. In 1950 he won a Fulbright fellowship, which enabled him to spend a year at the American Academy in Rome. Returning home, he made his living as an editor for the Philadelphia music publisher Theodore Presser, until Penn beckoned in 1960. Among Rochberg’s early compositions was the orchestral work Night Music, for which he won the Gershwin Prize in 1952. In 1957, he spent six months in Mexico on a Guggenheim fellowship.

Under its longtime conductor Eugene Ormandy, the Philadelphia Orchestra premiered Rochberg’s First Symphony in 1958. In Five Lines, Four Spaces (the source, unless otherwise indicated, for all quotations in this article), Rochberg summed up Ormandy as “a man of great ego given to famous fits of temper.” One such fit occurred during rehearsals—when Rochberg declined the maestro’s request to give the First Symphony a more emphatic ending, Ormandy snapped, “Far be it from me, a mere conductor, to tell a composer how he should write his music”—but on the whole the collaboration went well. The Philadelphians took the piece to Carnegie Hall, where it won over the audience and critics.

The American musical milieu in which Rochberg was making a name for himself owed much to an iconoclastic Austrian, Arnold Schoenberg. Early in the 20th century, Schoenberg had turned against tonality—the toolkit of major and minor keys that shaped the melodies, harmonies, and variations thereon in Western music from the 18th century on—for being inbred. Other composers had chafed against the constraints of tonality too. But where they contented themselves with introducing dissonance as the spirit moved them—Richard Strauss in his opera Elektra, for example, or Igor Stravinsky in his ballet score The Rite of Spring—Schoenberg made a clean break with tradition.

In the grip of a “militant ascetism,” as Alex Ross calls it in his book The Rest Is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century, Schoenberg declared the 12 pitches in an octave to be a row. After selecting a pitch in the row as his starting point, the composer following Schoenberg’s new rules was expected to use the remaining 11 pitches in order before sounding the first one again.

The system was less rigid than it might seem. You could navigate the row backward or work with only a part of it or even abandon it temporarily to gain an effect, but it was supposed to remain your organizing principle. The widespread adoption of Schoenberg’s innovation—along with a cousin known as serialism, which systematically regulated such elements as the length and loudness of notes—was partly the result of his musical brilliance. Schoenberg also had the good luck to attract Alban Berg and Anton Webern as disciples. As Ross observes, what originated as a personal style “became a movement when two equally gifted composers jumped in behind [Schoenberg].” Eventually, Stravinsky jumped in, too.

The United States proved especially receptive to the revolutionary European import, perhaps because classical music was so slow to mature here. A robust tradition of American painting sprang early from the brushes of George Caleb Bingham, Frederic Church, and James McNeill Whistler, among others. And 19th-century American literature was awash in talent and originality—think Emerson and Thoreau, Hawthorne and Melville, Whitman and Dickinson, and the one and only Mark Twain. American music, however, lagged behind. The set of 19th-century American classical composers who don’t sound like pale imitations of their European counterparts may consist of a single name: Louis Moreau Gottschalk.

Whatever the reason, Americans embraced this innovation from the heartland of classical music, especially after its principal architect, Schoenberg, emigrated to the States in 1934. Two decades later, Rochberg joined the ranks during his Roman sojourn—a decision he described as “cast[ing] my lot with the extremes of expressionism, with heightened, intensely personalized modernist projections of angst and forebodings of terror.” He also cited his “passion for making variations [which] took on renewed energy and enlarged scope with the manifold possibilities I saw inherent in the principles of the row.”

Rochberg composed numerous 12-tone pieces and won honors for several of them, but after a while he found the method confining, almost hobbling. “Where melodic thinking in tonal music was capable of producing long, extended lines,” he complained, “twelve-tone musical thought had the opposite tendency, toward brief statements.” Ultimately, he projected his dissatisfaction onto the whole Schoenbergian tribe: “I had found that twentieth-century American and European composers of the serialist persuasion sounded much more like each other than did eighteenth- and nineteenth-century tonal composers, who differed widely from each other in temperament, emotional temperature, and, above all, in capacity for melodic/harmonic invention.” To Rochberg’s ears, then, the inbreeding complained of by Schoenberg had resurfaced in the 12-tone row.

In his private life, meanwhile, Rochberg was grief-stricken. He and his wife had two children: a son, Paul, and a daughter, Francesca. Paul, a promising poet, was diagnosed with a brain tumor at age 17. In 1964, after four years of pain and suffering, he died; afterward, Rochberg said, he knew that his music had to change.

He declared his independence with his third string quartet (1972), a work of unabashed tonality. In the ensuing “tempest,” Rochberg was called “traitor,” and his quartet was dismissed as “retrogressive” and a “copout.” A notable dissent, however, was filed by New York Times critic Donal Henahan. “The appeal of the work,” Henahan wrote, “lies … in its unfailing formal rigor and old-fashioned musicality. Mr. Rochberg’s quartet is—how did we used to put it?—beautiful.”

Rochberg did more than revamp his own composing style, however. The philosopher in him stirred, taking aim at what he saw as a stultifying orthodoxy. Several of the essays collected in his book The Aesthetics of Survival: A Composer’s View of Twentieth-Century Music (revised and expanded edition, 2004) develop that theme.

In “Reflections on Schoenberg,” Rochberg noted a fear expressed by his fellow American Elliott Carter: “that his music cannot be remembered.” Rochberg transferred this caveat to 12-tone music, which in his opinion virtually defies memory.

In “The Aesthetics of Survival,” he went deeper, arguing that the human central nervous system balks when presented with musical notes joined in ways perceptible to the composer alone. He invoked the central nervous system because listeners respond to music not just mentally but also physically—by moving in rhythm or humming snatches from a piece after the performance has ended. It follows that a composer might do well to put his body into his craft—a near-impossibility, Rochberg believed, for those caught in the coils of a 12-tone or serialist regimen.

He saved his harshest criticism for aleatory music, in which what reaches the listener’s ear is a matter of chance. So, for example, the German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen instructed the pianist to decide as she went along in what order to play the movements of his new piano piece. The American John Cage composed a work whose every performance is governed by tosses of the I Ching. And Cage’s Imaginary Landscape No. 4 calls for 24 “performers” to “play” 12 radios, each tuned to a different station. Such works, Rochberg contended in his essay “The Avant-Garde and the Aesthetics of Survival,” condemn themselves to “self-extinction.”

Rochberg sloughed over the ludic aspect of aleatory music—isn’t Cage’s Imaginary Landscape No. 4 a provocative stunt that, like Marcel Duchamp’s urinal or Andy Warhol’s Brillo boxes, confronts us with the aesthetics of shock? At times, too, Rochberg could sound like a crank. In a 1988 essay called “News of the Culture or News of the Universe?” he linked arms with crabby old men everywhere to bemoan a world going to pot. Worse, he coined the ugly term “cultural AIDS” as a shorthand for Americans’ alleged “loss of psychic and intellectual immunity to Bad Art.” At its best, however, Rochberg’s indictment of 20th-century culture was pithily eloquent. “There is no greater provincialism,” he wrote in “The Avant-Garde and the Aesthetics of Survival,” “than that special form of sophistication and arrogance which denies the past.”

As for himself, from the mid-1960s on, Rochberg made eclectic music, mixing tonality and atonality and honoring his forebears by quoting from their works. His Third Symphony, subtitled “A Passion According to the Twentieth Century,” contains echoes of Heinrich Schütz, Bach, Beethoven, Mahler, and Charles Ives. And the third movement of Rochberg’s Sixth String Quartet is a set of variations on Pachelbel’s Canon.

Rochberg’s relationship with the prickly Ormandy became more fraught in the fall of 1961, when the Philadelphia Orchestra performed Night Music. In Rochberg’s telling, most of the time Ormandy displayed “genuine warmth and friendship,” perhaps out of respect for what the Rochbergs were going through with their son. But when Rochberg suggested that Ormandy program his Second Symphony—the one George Szell had done so well with in Carnegie Hall—Ormandy snapped, “Let the other George do it!”

They clashed again in 1969, after the maestro sat for a pre-season interview with the Philadelphia Inquirer’s music critic. “What am I to do?” Ormandy wailed. “Last year I consciously tried to play more new music, and you should read the letters I received. Audiences did not like the new works. In New York, after we played some of the programs, we had letters threatening to cancel and many which did cancel their subscriptions. This year we are doing less [new music], and the box office tells me we are doing much better in New York and here.” Ormandy also complained that new music was “so difficult to prepare.”

Rochberg took it upon himself to reply in a letter published in the Inquirer. “It is sad and depressing,” he wrote, “that Mr. Ormandy expresses such a lack of faith in the possibilities that anything worthwhile is being produced by composers either in this city or in any other American city. I cannot agree with him—obviously.” On reading that (and there was much more), Ormandy fell into what Rochberg called “an absolutely ulcerous rage … To all intents and purposes my public riposte … brought to an end my professional relationship with Ormandy for almost a decade—from 1969 to 1978.”

Ormandy may have been too quick to speak his unfiltered mind, but it’s hard to see what Rochberg hoped to gain by popping off like that, especially since he had done his own share of inveighing against new music. Perhaps it was the philosopher in him, the professor inhabiting the same body as the composer, who couldn’t let Ormandy’s apparent pandering to the box office go unchallenged.

In 1978 their feud reached its climax. Rochberg wrote a violin concerto for Isaac Stern, whose renown was such that Ormandy agreed to program the piece with Stern as soloist. As usual, Rochberg noted, Ormandy “proved to be the perfect concerto partner,” and after the final performance the composer tried to patch things up backstage. “I began to speak [to Ormandy] in an unbroken stream of words riding on the flush of good feeling, but quick as lightning, when I called him by his first name, ‘Gene,’ that single syllable, that unguarded familiarity on my part brought on a sudden and violent change in the man … he flew into a paroxysm of rage … his face purpled with overpowering anger … ‘how dare you call me by my first name … only my friends can call me “Gene” … you attacked me in public … in the newspaper … unforgivable.’” Ormandy’s tirade left Rochberg so shaken that he had to make his excuses and leave. Four years later, the maestro retired. He and Rochberg never reconciled.

The violin concerto has a curious history, by the way. Stern made it a personal showpiece, performing it a total of 47 times. Nonetheless he urged Rochberg to cut 14 minutes’ worth of its music. The composer reluctantly complied but was delighted when, years later, conductor Christopher Lyndon-Gee recorded the original version with soloist Peter Sheppard Skaerved and the Saarbrücken Radio Symphony Orchestra.

Ormandy aside, Rochberg was treated well by eminent conductors. Szell’s exhilarating rendition of the Second Symphony speaks for itself in a live performance available on YouTube. Georg Solti commissioned Rochberg’s Fifth Symphony and premiered it with the Chicago Symphony; the work, which was nominated for the 1986 Pulitzer Prize in music, is available on CD in a performance by the Saarbrücken RSO, again under Lyndon-Gee. And Rochberg credits Lorin Maazel with showing grace under pressure during a 1989 overseas tour with the Pittsburgh Symphony, on which Rochberg accompanied them. When bad news reached Maazel in Moscow—he’d missed out on a post he dearly wanted, the musical directorship of the Berlin Philharmonic—he rallied to lead the Pittsburghers in a knockout rendition of Rochberg’s Sixth (and last) Symphony. (The Sixth can be heard on YouTube in a fine live performance by the St. Louis Symphony, conducted by Raymond Leppard.)

The musicians who most endeared themselves to Rochberg, however, were the Concord Quartet, for whom he wrote four of his seven string quartets, including no. 3, the one marking his defection from the 12-tone camp. Rochberg loved the quartet’s “rambunctious” playing, and they loved him back. What the composer cherished as “a decade and a half of musical adventures together … often enough a kind of musical high-wire act” came to an end when the Concorders broke up in 1987. (The group’s interpretations of quartets nos. 3–6 are available on a two-CD set.)

When you listen to Rochberg’s music— at least the sizable fraction of it available on CD or YouTube—it’s hard not to notice an affinity between him and the stark modernism he sometimes decried. He wrote that his early Night Music embodies his characteristic “dark radiance.” He regarded his post-12-tone Fifth Symphony as an example of “hard romanticism,” as opposed to the “soft romanticism” of 19th-century music. Toward the end of Five Lines, Four Spaces, Rochberg speaks of having been shadowed by a sense that “our time, our Western civilization, has long since reached its limit and, with the giant blows of both world wars and world upheavals that accompanied and followed from them, began the Great Unraveling.”

And yet there is the Sixth Symphony, perhaps the most accessible and joyful opus Rochberg ever composed, especially its third and last section, which makes use of three distinct marches. One of them could serve as entrance music for a team of circus acrobats, and another recycles a Sousa-like number Rochberg had written for a regimental band in 1943. The symphony ends with a frenzy of timpani and one of those it’s-over-oh-wait-it’s-actually-not codas favored by Tchaikovsky. Hearing the Sixth can make you wish that Rochberg had indulged his appetite for body-conscious music by composing the music for a ballet.

In terms of audience response, the Pittsburgh Symphony’s Moscow performance of the Sixth may have been the apotheosis of Rochberg’s career. “[Maazel] fully grasped the play and brilliance of the three marches,” the composer recalled, “and—best of all—his sense of tempo was flawless. He raised the coda … to an unbearable pitch of emotional tension—and broke off. The audience rose to its feet in a unison furioso of responsive, noisy enthusiasm, the like of which could only warm the heart and memory of any composer.”

Passages like that can fuel a suspicion that George Rochberg’s dark radiance coexisted with a softly romantic heart.

Dennis Drabelle G’66 L’69 is the author, most recently, of The Great American Railroad War.

Wonderful article about a GREAT composer! It was an honor to premiere several of George’s works, a couple of them written just for me. His time will come – he was just ahead of it, as were many other great composers.