Dr.

William Bass III Gr’61 strode into his boss’s

office one day and informed him, “I need a place to put dead bodies.”

Under

different circumstances, this request might have prompted a phone call

to security. But Bass, then a young forensic anthropologist in charge

of a budding graduate program at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville,

had the law on his side. He needed to study the conditions under which

human flesh decomposes.

His

dean told him who to call and Bass soon found himself in charge of a former

trash-burning dump near the university’s hospital. Over the following

three decades, the Anthropological Research Facility he founded there

has served as a one-of-a-kind resource for law-enforcement agencies around

the country, as well as a training ground for many of the forensic anthropologists

practicing today. They call it ARF, but folks outside the fence simply

know it as “The Body Farm.”

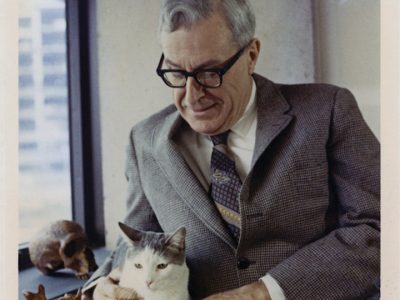

Bass,

now a professor emeritus, remains director of the university’s Forensic

Anthropology Center, which oversees this unusual outdoor lab. He is also

active as a consultant on criminal cases, helping to estimate time since

death and identify victims.

One

might expect someone who has spent a large part of his professional life

cultivating a property that sounds like it belongs in the Addams Family’s

backyard to possess a morbid disposition. But the 72-year-old scientist,

who discussed his profession over the telephone between sips of tea one

May afternoon, sounds downright jovial.

“It

was a need-to-know decision,” he says of his idea for the outdoor research

facility. “The first thing police ask you [in a case] is not who is that

individual, but how long have they been dead? Because the sooner you get

on the chase, the more likely you are to solve a crime.”

Bass

found that after working in Kansas to identify skull remains for police

that half the cases he was getting in more densely populated Tennessee

were maggot-covered bodies. “If you die in Tennessee, the possibility

of being found—or smelled is a better word—in the active-decay

stage is greater.” Bass soon realized that he needed a place to research—and

teach others—exactly how this process unfolds.

To

enter the three-acre “farm,” one goes through a chain-link fence topped

with razor wire (“to keep animals and curious humans out”) and then a

wooden modesty fence. The smell of decay “hangs in the air” during the

warm months and is immediately apparent when the gate is opened. Scattered

amid groupings of trees and shrubs which simulate the open woods of Tennessee

are anywhere from 20 to 40 corpses at one time in varying stages of putrefaction.

They may be half-buried, stowed in a car trunk or even submerged in water.

“You kind of name it, we try to reconstruct all the events that have occurred.”

FBI agents come down here each year for short courses, learning what to

look for when they excavate. They study the various kinds of insects that

feed on corpses, from blowflies to beetles, and the clues they can provide

about the time of death. Cadaver-dog trainers show up to study the psychological

effects on a dog when it encounters multiple dead bodies —as was the case

after the bombing of the Oklahoma City federal building.

The

skeletal remains are eventually cleaned, numbered and stored in boxes

at an indoor lab, labeled by age, gender and race, and are used as a research

tool for students. Bodies end up here because they haven’t been claimed

by a family member and are passed on through the medical-examiner system,

or they have been intentionally donated to science. More than 300 people

have willed their remains to the Body Farm, which was so nicknamed by

mystery writer Patricia Cornwell. She has consulted frequently with Bass

for the forensic details in her popular books.

Bass

first encountered anthropology in elective courses he took while majoring

in psychology at the University of Virginia. “I was hooked then, although

I didn’t realize it,” he recalls. He went on to get his master’s degree

at the University of Kentucky, switching majors to anthropology toward

the end of his first year. While in Kentucky, he had the opportunity to

identify a woman killed in a truck wreck and knew afterward that “That’s

what I wanted to do.” Bass came to Penn for his doctoral work and sought

a graduate assistantship under the late Dr. Wilton Krogaman, the famed

anthropologist who had been featured in Life magazine for his work

several years earlier. After graduation, he taught briefly at the University

of Nebraska, and then for 11 years at the University of Kansas —Lawrence,

before arriving at UT. By his estimate, Bass has trained 65 percent of

the practicing forensic scientists in the United States during his career.

“I

lost two wives to cancer,” Bass says. “So I don’t like mourning. I don’t

like death. I don’t like funerals. But a forensic case I never see as

mourning or death. It is a scientific experiment to see if I have enough

ability, enough knowledge, to look at that individual, see who that individual

is and determine what happened to them.”