Within the ancient ruins of a Maya settlement, an anthropological archeologist seeks deeper meaning.

Mummies. From an early age, Charles Golden Gr’02 felt their allure, beginning his adventure into the past when he was a little boy and his parents took him to Chicago’s Oriental Institute Museum.

“To see these things and realize Oh, my gosh, they’re real! was amazing,” he recalls. “The excitement and spookiness of mummies scared the heck out of me and made me interested. But that’s what I thought archaeology was.”

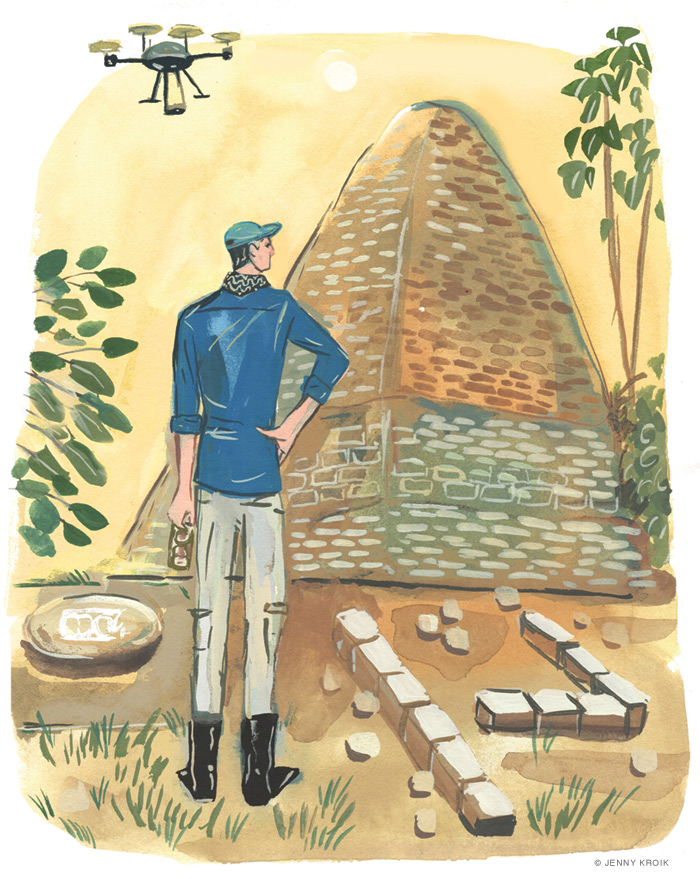

Turns out, there was a lot more. Now a professor of anthropology at Brandeis University, Golden has devoted the past 30 years to studying the Maya civilization, not Egyptian relics. He and his longtime research partner Andrew Scherer, a bioarcheologist at Brown University, have used drones and the laser-sensing technology Lidar—as well as old-fashioned shoe leather—to help discover dozens of previously undocumented sites and more than 5,000 structures in a 130-square-mile area in and near the Mexican state of Chiapas (which borders Guatemala).

As a young Penn graduate student, Golden got the opportunity in 1997 to do summer research in remote northwestern Guatemala at the Maya site Piedras Negras, where the late Penn professors and renowned archaeologists Linton Satterthwaite Gr’43 and J. Alden Mason led 1930s digs. “Here was this near mythical site that had this Penn connection,” Golden recalls. “It was so exciting to me. I volunteered, and I found myself on a boat going through the jungle in the middle of nowhere to Piedras Negras, and I thought, What the heck did I get myself into?”

At Penn, he worked with Penn Museum archivist Alessandro Pezzati C’94 CGS’01 to review Mason’s on-site notes and photos. During the excavations, he uncovered fun Penn connections. “We would sometimes find tools from the 1930s that had been lost and forgotten,” he recalls.

Since 2018, Golden’s research has focused on a jungle site in Chiapas that sprawls across 100 acres—the lost city of Sak Tz’i (which means “White Dog” in the ancient Mayan language). A 45-foot-tall pyramid where royals may have been buried dominates the terrain. Masses of snarled vines and mysterious lumpy earth mounds hide what were once grand plazas, temples, and reception halls.

Wedged between more powerful city-state kingdoms, Sak Tz’i thrived from 600 to 900 CE on the site of Lacanjá Tzeltal, which was first settled in 750 BCE. At its peak, no more than 1,000 people lived there, yet for hundreds of years it successfully navigated the political landscape, fighting wars and making alliances as rival kingdoms fought to expand their size and influence. Golden says two key questions drive his research: “How did these people maintain their independence? Why was this place important?”

Scott Hutson, an archaeologist at the University of Kentucky, hails Golden for assembling at Sak Tz’i specialists in the analysis of ancient pottery, seeds, soil, stone tools, art and text, and animal remains. “This is a model for how you work an ancient Mayan site,” Hutson says. “It’s something that’s really exciting about Charles’ scholarship. His long-term commitment to this region is paying off. He’s got perseverance.”

Being called the discoverer of Sak Tz’i makes Golden uneasy. Locals knew of its existence for years. A former Penn graduate student named Whittaker Schroder Gr’19 learned of it in 2014, and Golden’s excavations began only after years of negotiations with the landowner and approval from the National Institute of Anthropology and History.

“Discover is a convenient word,” he says. “We have formally documented Sak Tz’i and expanded the knowledge of its deeper history. The fact that the site is there is not what we’re discovering—it’s how people lived there. As an anthropologist, I want to understand them as people rather than as rocks, broken pottery, or stone tools. I want to understand how they lived their lives in deeply meaningful ways. What I’d like to know about the Maya is how did they deal with their everyday world in ways that are profoundly human?”

The Maya thrived for about 2,000 years. Without the use of metal tools or the wheel, they created one of the world’s first written languages, a robust agricultural system, and astronomical calculations of mind-boggling accuracy.

For reasons that remain murky, their civilization faded away around 900 CE. Scholars agree that a long-term drought afflicted present day southern Mexico and areas to the south, but Golden sees another force behind the Maya’s demise.

“It’s not drought that starves people,” he says. “It’s the inability of political actors to solve the problems caused by the drought. The political system couldn’t hold together. Something dramatic happened. Cities were abandoned. We don’t see mass burials or other evidence that they all died. Instead, people basically picked up and walked away.”

For him, the fate of the Maya is a cautionary tale. “The Maya never disappeared. Millions of people speak Maya languages today. They founded new cities that the Spanish promptly set about trying to destroy.

“One thing I take away from archaeology in general, not just the Maya, is a sobering message,” he says. “No civilization is eternal, and that’s an object lesson we should pay close attention to. On the other hand, archaeology is a story not of collapse and abandonment but one of transformation and persistence. It’s a story we can be hopeful about.”

Like modern Americans, the Maya used tobacco, drank alcohol (often to excess, as depicted in stone wall panels), and even took hallucinogenic drugs, which were administered via enemas.

They also loved sports. Today at Sak Tz’i, rubble and small loose stones litter what was a 350-foot-long, 15-foot-wide ball court with sloping sides. Teams vied for victory by passing a rubber ball using their shoulders and hips. “It was played for fun, sport, and gambling. We know from Spanish accounts people would gamble away their wealth on these games as we do today. But it was also a ritual act,” Golden says. “Players were ritually entering the underworld, getting in contact with deities, and reenacting mythological stories.”

Some aspects of Mayan life remain inscrutable. Their glyphs (or script) carved in stone refer to a ritual in which a man experiences his “first darkness.” Others depict a blood-letting ceremony: women pull thorny vines through holes in their tongues and men pierce their penises with stingray spines.

“When the Spanish arrived, they looked at the Maya and said, These people are crazy violent,” he says. “They have human sacrifices and do all these terrible things. Oh, and now we’re going to burn them at the stake in our Inquisition. The inability of the Spanish or us to see those commonalities, I think, is what we have to get past.”

—George Spencer