The Penn Museum’s new Eastern Mediterranean Gallery casts the cradle of Abrahamic religions and alphabetic innovation as a cosmopolitan sphere—not just a conflict-ridden one.

The new Eastern Mediterranean Gallery at the Penn Museum showcases visually arresting objects from the University’s 20th-century excavations: clay sarcophagi that marry Egyptian ritual and Canaanite craft, Roman-influenced limestone mortuary statues from Syria, marble column capitals sculpted for a Roman temple and repurposed two centuries later for a Byzantine church.

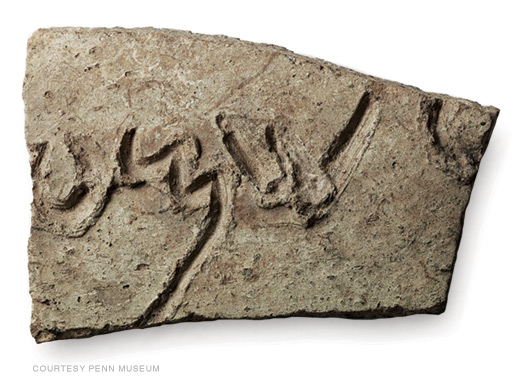

But some of the most interesting stories involve artifacts that might be easy to overlook. A tiny lead “curse tablet,” excavated at Beth Shean, Israel, and dating from 300–400 CE, is a case in point. The tablet was “a very common magical tool used by all faiths” and exemplifies the frequent blurring of religious boundaries, said Eric Hubbard, a PhD candidate in anthropology and one of the gallery’s four curators.

Created by a religious specialist for a woman in a financial dispute, the tablet calls upon an eclectic pantheon of gods—Egyptian and Babylonian deities, as well as biblical angels—to curse the woman’s antagonists. “You throw the whole kitchen sink at your problem,” Hubbard explained. “To activate the spell, you roll up the lead tablet, pierce it with a nail, and place it in a sacred or significant place.”

The melding of diverse influences is one of the key takeaways from the gallery, subtitled “Crossroads of Cultures.” It debuted in November with more than 400 artifacts from the area now encompassing Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, the Palestinian territories, and Cyprus. They date from the Middle Bronze Age (2000–1600 BCE) to about 1800 CE, and draw on excavations at Beth Shean, Gibeon (Israel), Tell es-Sa’idiyeh (Jordan), Baq’ah Valley (Jordan), and Kourion (Cyprus).

This area has too often been identified solely with conflict, remarked Christopher Woods, the museum’s Williams Director, at a November 17 press preview. “Our gallery reaches beyond these stereotypes to uncover a much more complex historical narrative,” he said, depicting the region as a cosmopolitan “crossroads of ideas” and “crucible of innovation.”

In an era of massive empires, “this is an area that’s never really in charge,” said lead curator Lauren Ristvet, the Dyson Associate Curator of the museum’s Near East Section and associate professor of anthropology. “When it’s autonomous, it’s never the major player in the world. And yet, despite that, it’s an area that’s had an enormous impact on much of the rest of the world,” especially in terms of religion—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam all originated here—and the spread of literacy.

Ceramics, glass, gold jewelry, mosaics, clay figurines, stelae, coins, and cylinder seals are among the objects on view. One exhibit touches on Penn excavations undertaken from 1921 through the 1980s. The gallery also includes touchable replicas, sophisticated digital interactives, a partial reconstruction of a 14th-century BCE ship that wrecked off the Turkish coast, and a button whose push summons the aroma of frankincense. A replica of a 12th-century BCE Egyptian garrison portal at Beth Shean is studded with limestone fragments that may have come from the local commander’s residence.

The organization of the 2,000-square-foot gallery—the latest achievement in the museum’s ongoing modernization of its galleries and public spaces—is primarily thematic. Situated between the museum’s Rome Gallery and its Ancient Egypt exhibition, it has two entrances and is divided into three sections.

“Power and Conflict” details the rise and fall of various imperial powers—including the Egyptian, Assyrian, Babylonian, Persian, Greek, Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman Empires—that ruled the region. “Creativity and Change” highlights religious continuities and transformations, and describes the origins and diffusion of the alphabet. The gallery’s central section, “Coexistence and Connection,” emphasizes trade, migration, and the interpenetration of the region’s cultures.

“Religion and power and politics are closely intertwined and are never really separate,” said Hubbard. “We tried to focus on what archaeologists do best, which is reconstruct patterns and behaviors. We really focused on generally shared traditions over time and space.”

There are some surprisingly human touches, moments when the distant past seems achingly familiar. A scribal text from about 1200 BCE evokes the universal emotions of warriors stranded far from home. “I am dwelling in Damnationville,” an Egyptian soldier says, according to the text. “I spend the day … eyeing the road [from Egypt] with longing.”

Nestled within the reconstructed ship is an assortment of items that weren’t from the wreck itself but might have been carried in the cargo hold of a similar ship. Co-curator Joanna S. Smith, a consulting scholar in the museum’s Mediterranean Section, pointed out stirrup-handled jars—a shape developed in Greece but found throughout the region, sometimes imported and sometimes copied by local craftsmen. One jar from Israel was manufactured a century after that form went out of style, she said.

Co-curator Virginia Herrmann, a consulting curator at the museum, confessed partiality to a set of “exquisite little ivory plaques” used to decorate royal thrones or beds. “When you first look at them,” she said, “they look so Egyptian” on account of motifs such as a sphinx with a falcon head and the god Horus sitting on a lotus. “But these are actually made in the Phoenician style,” she said, and were excavated in northern Iraq, from the palaces of the Neo-Assyrian emperors who had plundered them. Symbols of royalty, the plaques represent “supernatural protection of fertility and life and divine authority,” Herrmann explained.

“They really capture that idea of movement of people, of goods, through trade and imperialism that this region is so known for,” she added.

The new gallery replaces one that had focused on Canaan and ancient Israel. “We were trying to showcase the collection in a modern way, trying to make it multisensory, really bring the past to life,” said Jessica Bicknell, the museum’s director of exhibitions. “We’re also trying to people the galleries [by] telling stories of individuals. We’re incorporating new technologies. We’re trying to expand the age of our audiences.” Another aim was to be “really clear about the colonial powers that were influencing early archaeology versus how we would do it today.”

Ristvet explained that the goal was to establish that the ancient Eastern Mediterranean sphere “was not just a space of conflict but this really interesting creative space,” with a history of cultural coexistence. “This is an area of the world that a lot of people feel connected to,” she said. “But we thought we might make the familiar a little strange.”

—Julia M. Klein