Loren Eiseley was associated with no great discoveries in his field of anthropology, “awkwardly shy” and “not very comfortable with students” in the classroom, a disaster as Penn’s provost—and a writer of unmatched brilliance on the natural world and the human condition.

By Dennis Drabelle | Photos courtesy Penn Archives

In his autobiography, A Quest for Life, Ian McHarg reports having lunched with Loren Eiseley G’35 Gr’37 once or twice a year during their overlapping time on the Penn faculty—from the late 1950s to the late ’70s. They must have made quite a contrast: on one side of the table, McHarg, the ebullient, Scottish-born landscape architect and stalwart of the 20th-century environmental movement [“A Man and His Environment,” Sep|Oct 2019]; on the other side, Eiseley, the reserved Nebraskan who taught anthropology but thought of himself as an evolutionist and resented his fellow scientists’ disdain for those who, like him, wrote primarily for the lay reader. Too bad we don’t have bootleg tapes of the back-and-forth between two eminences with so much to talk about.

Eiseley not only wrote an autobiography of his own, All the Strange Hours: The Excavation of a Life (1975); he also revealed himself in his scintillating essays, which the Library of America has collected and published as a two-volume set. They depict a human sponge who could soak up literary material almost anywhere and anyhow: while hopping freights in the American West, marveling at the impressions left on stone by ancient rainfall, watching pigeons in downtown Manhattan, or coexisting with mice in Wynnewood, the Main Line suburb where he lived while teaching at Penn.

A rather different Eiseley emerges from reminiscences by his friends and colleagues: a case of arrested development who was never fully comfortable in the roles that a college professor is supposed to play. He took part in many expeditions, but you won’t find his name attached to any great discoveries made in the field. On the other hand, few other practitioners of anthropology and its kinfolk archaeology and paleontology have used them so effectively to comment on the human condition—and occasionally the universe’s condition.

Born in 1907, Eiseley came from German stock on his father’s side, Anglo-Saxon on his mother’s. For the growing boy, it was often either Shakespeare or silence. His father, Clyde, had committed long passages of the Bard’s plays to memory and enjoyed reciting them to the younger of his two sons (the other son, from a previous marriage, was only a fleeting presence in young Loren’s life). But Clyde worked long hours in a succession of low-paying jobs, including store clerk and traveling salesman, leaving Loren in the hands of his mother, Daisy, who was losing both her hearing and her mind.

Left on his own, Eiseley became an avid reader and a wanderer through his hometown of Lincoln. Surprisingly for a future scientist, he had no head for math but excelled in his English courses. As early as the eighth grade, he knew where he was going. “I have selected Nature Writing for my vocation,” he wrote in a theme, “because at this time of my life it appeals to me more than any other subject.”

As a high school senior, Eiseley handed in such a polished story about a dog in Alaska that he was accused of plagiarism. His teacher, who had watched the tale develop from scratch, stood up for him; the vindicated writer entered the story in a contest held by the Atlantic Monthly, which gave it an honorable mention. He had meanwhile blossomed into a strapping youth with an infectious smile, enough athleticism to captain the football team, enough popularity to be elected president of the senior class. For all his local prominence, though, Eiseley remained, in the words of his biographer Gale E. Christianson, “awkwardly shy.”

After his graduation in 1925, Eiseley and three buddies set off for California in a jalopy that kept breaking down, leaving them to carry on by hopping freights. In the fall of that year, Eiseley enrolled in the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. For his freshman English course, he wrote another precocious paper, which drew another charge of plagiarism. He beat the rap again, only to flunk out as a sophomore because he had a hard time learning foreign languages.

Readmitted in 1927, Eiseley mismanaged the rest of his undergraduate career. Instead of formally dropping a course that wasn’t to his liking, he would just block it out of his mind. There were more hiatuses, but he had two pillars to lean on: creative writing—by the time he finally graduated from Nebraska in 1933 with a BA in anthropology and English, he had published some poems in the literary magazine Prairie Schooner—and his seven-years-older girlfriend, Mabel Langdon, described by a friend as “his mother, his sister, his cousin, his friend; she was his stay.”

As a junior member of a paleontological expedition that summer, Eiseley unearthed a fossil in the badlands of northwestern Nebraska that he looked back on as, in Christianson’s words, “his single most memorable discovery”: the skull of a saber-toothed cat that was probably killed in combat with another of its kind. Thanks in part to an endorsement by a Penn professor he’d encountered in the West, Eiseley overcame his ragged college transcript; Penn accepted him as a grad student in anthropology starting in September of 1933.

He found a much-needed mentor in the eccentric Frank Speck, the subject of a vivid word-portrait in a New Yorker article published last year. Writing about the fate of the Penobscot language, Alice Gregory identified Speck as “an anthropologist specializing in the Algonquian and Iroquoian peoples. … Speck kept office hours in a book-lined neo-Gothic chapel filled with living snakes and lizards, and was known to shoot arrows from a crossbow into the door.” A medical student working in Speck’s office, Gregory continued, “memorized Penobscot vocabulary while keeping an eye on a white fox, which hid behind a leaking radiator.” Eiseley himself came to have such an affinity with foxes that Christianson titled his biography Fox at the Wood’s Edge.

Though delighted with Penn’s formidable anthropology department, Eiseley missed Langdon and groused about Philadelphia’s scarcity of diversions for someone as cash strapped as himself. Sizing up the newcomer as “kind of boyish for his age,” Speck came to the rescue by taking him to such exotic (to a Cornhusker) sites as South Street—then the cultural center and business district for the city’s Black residents—and the New Jersey Pine Barrens.

A second-year fellowship helped, but Eiseley was still just getting by and hard-put to acquire the reading knowledge of German expected of a PhD candidate in the sciences. He figured that the MA he received in February of 1935 would be the end of the line.

He retreated to Lincoln, took part in the excavation of ancient Native American burial sites, studied German with a tutor, and worked on the Nebraska volume of the WPA series of state guidebooks. His supervising editor remembered him as “a case of prolonged adolescence [who] seemed actually fearful of making his own way in the world.” He also suffered from bouts of depression.

Penn coaxed Eiseley back with another fellowship, and in 1937 he scored one triumph after another. His tale of freight-hopping, “The Mop to K.C.,” won the equivalent of an honorable mention in the Best Short Stories of 1936; he passed his German exam; and he received his doctorate. Reminiscing about this stage of his life in All the Strange Hours, Eiseley gave a sense of how wide-ranging an anthropological education can be: “I knew a great deal of ethnological lore from the Jesuit Relations of the seventeenth century, about divination through the use of oracle bones. I knew also about the distribution of rabbit-skin blankets in pre-Columbia America and the four-day fire rites for the departing dead. And mammoths gone ten thousand years, I knew them, too.”

More pithily in the title essay of his collection The Unexpected Universe, Eiseley explained what a practicing archaeologist does. “He finds, if imprinted on clay, both our grocery bills and the hymns to our gods.”

After Eiseley landed his first teaching job in the sociology department of the University of Kansas, he and Langdon got married. In 1940, he obtained a post-doctoral fellowship from Columbia University and the Museum of Natural History; the couple made ends meet in New York by combining his stipend with her earnings as a part-time typist for Rex Stout, author of the Nero Wolfe mysteries. A friend got them invited to a cocktail party where Orson Welles and his girlfriend (and later wife) Rita Hayworth were the main attraction but recalled that Loren and Mabel “didn’t mingle; they just sat there together.” Also that year, Eiseley signed a contract to write a book to be called “They Hunted the Mammoth: The Story of Ice Age Man”; but World War II intervened, and the project was cancelled. A combination of poor eyesight and a shortage of college teachers exempted him from war service, and he began supplementing his scholarly articles with pieces for the more accessible Scientific American.

A move to Oberlin College and summers of teaching at Columbia and Penn bear witness that, shy though he might be, Eiseley knew how to work the levers of academic advancement. His efforts culminated in 1947 with a dual appointment at Penn: professor of anthropology and chairman of the department. One of his trademark characteristics had stayed with him, however: a new friend, the novelist Wright Morris, took to calling him “Schmerzie,” short for Weltschmerz, or world-weariness.

An anthropology student who assisted Eiseley as a grader of papers later described him as “not a good teacher but a wonderful lecturer. His lectures were very, very effective—the style you find in his essays. … Now, when I say that he was not a good teacher, I think Loren was always very uncomfortable with students.” The wonderful lecturer was soon earning extra money by holding forth outside the classroom. On YouTube you can hear him regale the audience at an unspecified branch of the Young Women’s Hebrew Association in 1968. His voice is pleasant and confident, and if he pauses frequently to search for the right word, he nearly always finds it.

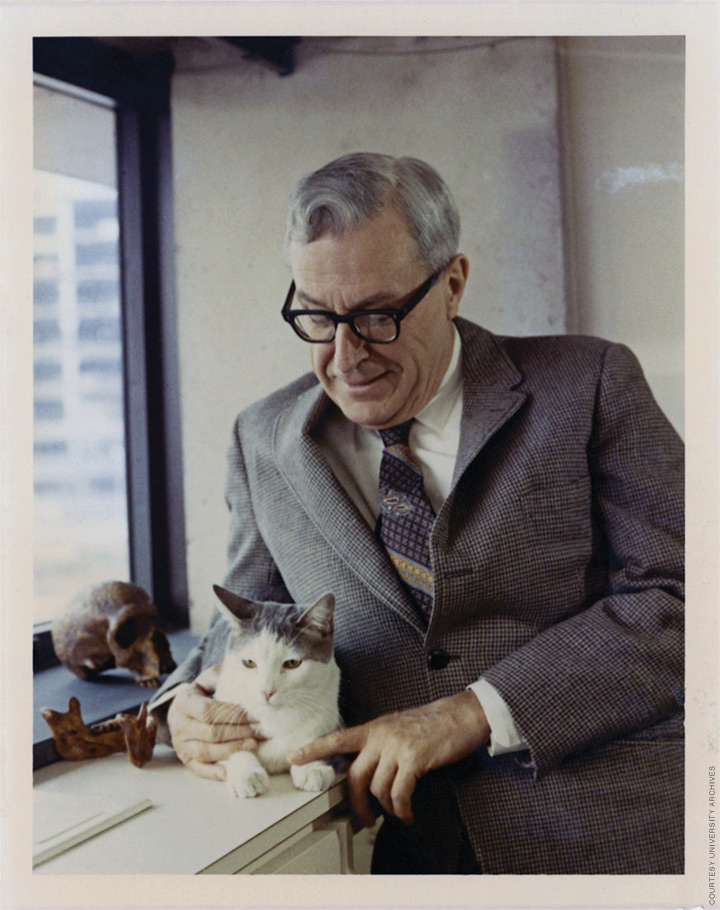

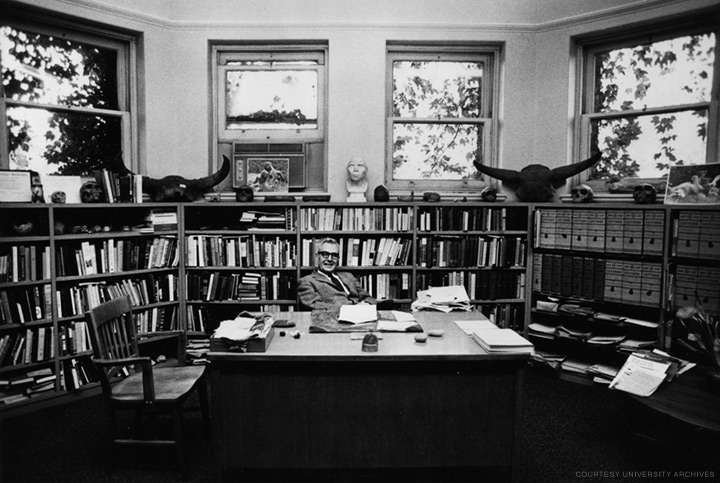

While Eiseley talks, the YouTube listener can inspect a photograph of him in his Penn office, which is cluttered with books and decorated with pertinent artifacts (above). Atop a bookcase behind him, for example, sits a bust mentioned by Kenneth Heuer, editor of The Lost Notebooks of Loren Eiseley. Whenever Froelich Rainey, longtime director of Penn’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, joined Eiseley for lunch in that office, “the two scholars would laughingly but affectionately toast the prehistoric men present [including] Australopithecus africanus, ‘the missing link,’ represented by a plaster statue.”

Eiseley was no more at ease with his peers than he was with students, as the Penn hierarchy discovered in the late 1950s after making him provost—the University’s chief academic officer. In a 1984 interview, Robert E. Spiller C1917 G1920 Gr’24 Hon’67, principal editor of the landmark Literary History of the United States [“The Work of a Generation” Sep|Oct 2013], remembered an occasion when Eiseley ran a faculty meeting. Seated at the head of a long conference table, he looked “like God Almighty but helpless as a child. The meeting got nowhere; he couldn’t point up the issues; he couldn’t pull it together; he couldn’t direct the people there.” Going around Eiseley’s back to deal with his vice provosts—historian Roy F. Nichols and English professor Sculley Bradley C1919 G1921 Gr’25—became standard operating procedure. After a year and a half in the job, Eiseley stepped down.

Ultimately, however, Spiller threw up his hands and called his illustrious colleague “a first-rate Loren Eiseley and I’ll let it go at that.” University president Gaylord P. Harnwell Hon’53 seemed to have reached the same conclusion: as consolation for the lost provostship, Harnwell created ex nihilo the position of university professor in the life sciences and gave it to Eiseley, who for all his quirks and shortcomings was now a living Quaker treasure.

The first collection of Eiseley’s essays, The Immense Journey, had appeared in 1957. A major selling point was a piece called “The Judgment of the Birds,” originally published in The American Scholar, the magazine of Phi Beta Kappa. “Judgment” flits from pigeons in Manhattan to the Badlands, where Eiseley once watched smaller birds rebuke a raven for making off with a nestling. At length, however, the protestors got over their outrage and moved on, sonically speaking. “There, in that clearing,” Eiseley wrote, “the crystal note of a song sparrow lifted hesitantly in the hush. And finally, after painful fluttering, another took the song, and then another, the song passing from one bird to another, doubtfully at first, as though some evil thing were being slowly forgotten. … They sang because life is sweet and sunlight beautiful. They sang under the brooding shadow of the raven. In simple truth they had forgotten the raven, for they were the singers of life, and not of death.”

The American Scholar’s then editor, Hiram Haydn, reported that “Judgment” drew “a veritable waterfall of praise.” Haydn doubled as editor in chief of Random House, and that’s where Eiseley’s collection found a home. In my opinion, however, the piece that follows “Judgment” in The Immense Journey is even better. “The Bird and Machine” takes Eiseley back to his salad days in the West, when he worked for an outfit charged with capturing birds for zoos. In a remote, uninhabited cabin, he found a mating pair of sparrowhawks and managed to bag the male. What happened when Eiseley had second thoughts about his mission should be left for the reader to discover on their own—let’s just say that the episode ends with rapturous caroling by the birds and their chronicler. With those two avian essays and a later batrachian one, “Big Eyes and Small Eyes,” in which Eiseley skips along with a platoon of skipping toads, he demonstrated that, given the right circumstances, his dour temperament could give way to rousing joy.

The Immense Journey overcame a slow start to sell briskly and win favor with New York Times book critic Orville Prescott: “It would be possible to read [the essays] for their content alone and to be quite satisfied with Mr. Eiseley’s ability to instruct. But it would be a dull clod indeed who would do so and the experience would be almost … like reading Shelley for information about skylarks.”

The book’s success proved replicable. Eiseley was to publish four more essay collections in his lifetime: The Firmament of Time (1960), The Unexpected Universe (1969), The Invisible Pyramid (1970), and The Night Country (1971); a sixth, The Star Thrower, came out in 1978, a year after his death from cancer at age 70. His next book after Journey, however, was a full-length examination of a single topic: Darwin’s Century: Evolution and the Men Who Discovered It (1958). Advancing the thesis that “great acts of synthesis are not performed in a vacuum,” the book dwells on such all-but-forgotten precursors to Darwin as the Scottish journalist Robert Chambers (1802–1871). Thanks to Chambers’s 1844 book, Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, Eiseley writes, “the world of fashion discovered evolution,” though not how the process worked (by natural selection, which was left for Darwin to pin down). With an eye for the telling detail, Eiseley traces Chambers’s interest in variation within a species to a personal oddity: “Both he and his brother William had been born full hexadactyls, that is, with six digits on both hands and feet.” Although Darwin’s Century won the Phi Beta Kappa science prize, it is not included in the Library of America set, which gathers essays only.

Evolution was more to Eiseley than just an explanation of how species develop. He also thought deeply about the process’s implications for humans’ image of themselves. His essay “Little Men and Flying Saucers,” originally published in Harper’s magazine during the 1950s UFO craze and reprinted in The Immense Journey, shows him at the height of his speculative powers.

He first makes the point that with the theory of evolution Darwin “engineered what was to be one of the most dreadful blows that the human ego has ever sustained: the demonstration of man’s physical relationship to the world of the lower animals.” Eiseley goes on to consider “an aspect of Darwin’s discoveries which has never penetrated to the mind of the general public. It is the fact that once undirected variation and natural selection are introduced as the mechanism controlling the development of plants and animals, the evolution of every world in space becomes a series of unique historical events. The precise accidental duplication of a complex form of life is extremely unlikely to occur in even the same environment, let alone in the different background and atmosphere of a far-off world.”

Eiseley then elaborates on his phrase “extremely unlikely to occur.” He acknowledges that, somewhere in the rest of the universe, “There may be wisdom; there may be power; somewhere across space great instruments, handled by strange, manipulative organs, may stare vainly at our floating cloud wrack, their owners yearning as we yearn. Nevertheless, in the nature of life and in the principles of evolution we have had our answer. Of men elsewhere and beyond, there will be none forever.” Among Eiseley’s friends, incidentally, was the science fiction master Ray Bradbury, who started things off by writing him a fan letter. “A reaction such as yours,” Eiseley replied, “tempts me to steal a little more time for some arm chair wondering about the universe.”

By the time of his death, Eiseley had hosted the TV series Animal Secrets on NBC, been elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters, and won a Guggenheim fellowship and the John Burroughs medal. For an epitaph, we can hardly do better than quote from his own homage, in his essay “Strangeness in the Proportion,” to the subspecies to which he belonged.

“Even though they were not discoverers in the objective sense, one feels at times that the great nature essayists had more individual perception than their scientific contemporaries. Theirs was a different contribution. They opened the minds of men by the sheer power of their thought. The world of nature, once seen through the eye of genius, is never seen in quite the same manner afterward. A dimension has been added, something that lies beyond the careful analyses of professional biology.”

Dennis Drabelle G’66 L’69 is the author, most recently, of The Power of Scenery: Frederik Law Olmsted and the Origin of National Parks.