“Human survival and the survival of life on earth depend upon adapting ourselves and our landscapes—cities, buildings, gardens, roadways, rivers, fields, forests—in new, life-sustaining ways,” warns Dr. Anne Whiston Spirn GLA’74.

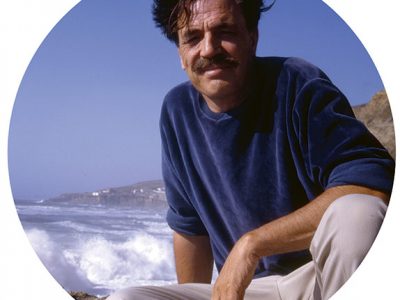

Spirn, the former chair of the Graduate School of Fine Arts’ department of landscape architecture and regional planning—and now a professor of landscape architecture and planning at MIT—was named winner of the 2001 International Cosmos Prize for her work promoting the harmonious coexistence of nature and humankind. She is the first woman and the first designer/planner to be awarded this honor.

Spirn is the author of The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design, which looks at the consequences of cities’ failures to adapt to the natural environment, as well as success stories, and The Language of Landscape.

For more than 15 years Spirn has used West Philadelphia as her main laboratory (www.upenn.edu/wplp), working since the mid-1990s with students, teachers, and community members in the Mill Creek neighborhood. The floodplain of Mill Creek is now buried in a sewer and Spirn has taught several courses to investigate how vacant lots in the neighborhood might be redesigned to detain stormwater, provide local open space, and stem problems of flooding and subsidence.

But her work goes beyond these issues to include larger themes of community development and neighborhood deterioration, public education and employment prospects. “I looked for ways to knit together those concerns,” Spirn says.

“I discovered that people had a hard time understanding that cities are part of nature. [Local] teachers would take kids and bus them out to Andorra Nature Center. What they were seeing there were many of same plants growing outside the school. It’s nature when they see it out there, but not nature when they see it a block from the school. To me it was tragic. Also, these kids were depressed about the condition of their neighborhood and thought it was their fault. The kids I was working with, eighth graders, started talking about how relieved they were to learn about things like red-lining and how that impacted the ability of people to get loans for mortgages or home improvements or business expansion. Their response wasn’t anger to learn about this. It was relief [to know] it wasn’t their fault.”

Spirn and Penn students worked with nearby Sulzberger Middle School to develop a curriculum around the theme of the watershed and the local community. Students learned to “read” the landscape of their neighborhood, using their own eyes and imaginations as well as primary documents, including old maps, photographs, and tax records. They planned a miniature golf course dedicated to the past, present, and future of Mill Creek and designed a water garden and outdoor classroom on a vacant lot next to the school.

Though she now lives in Boston, Spirn is still working with the Mill Creek neighborhood, where “I have so many close friends,” and is teaching a class at MIT this spring in which half her students collaborate with Sulzberger students by computer to tell their own stories about the neighborhood.

Spirn is also busy finishing her latest book, tentatively titled Telling Landscape. It features essays and color photographs from all over the world of “wild landscapes, ordinary vernacular landscapes, and what I would call ‘high-design landscapes.’” The book uses photography as a form of research, as well as an art form, to understand landscape and “see the ways natural processes intersect with cultural processes.” Her next project will be a series of three books about her work with the Mill Creek Watershed.