Mothballed for so long it was forgotten, a dark Courbet landscape returns to the light.

In 2016, soon after marking its 100th anniversary, the School of Dental Medicine set about sprucing up the building endowed by its founding benefactor, pioneering dentist and art collector Thomas W. Evans. Workers cleaning out the basement dumped a couple boxes on the desk of Liz Ketterlinus, Penn Dental’s vice dean of institutional advancement. The dusty contents included, among other errata, a couple hundred 19th-century French calling cards. Ketterlinus called Lynn Marsden-Atlass, who curates the University’s art collection and had recently helped mount an exhibition of Evans’s objets d’art at the Arthur Ross Gallery [“Arts,” Sep|Oct 2015]. Marsden-Atlass arrived within the hour.

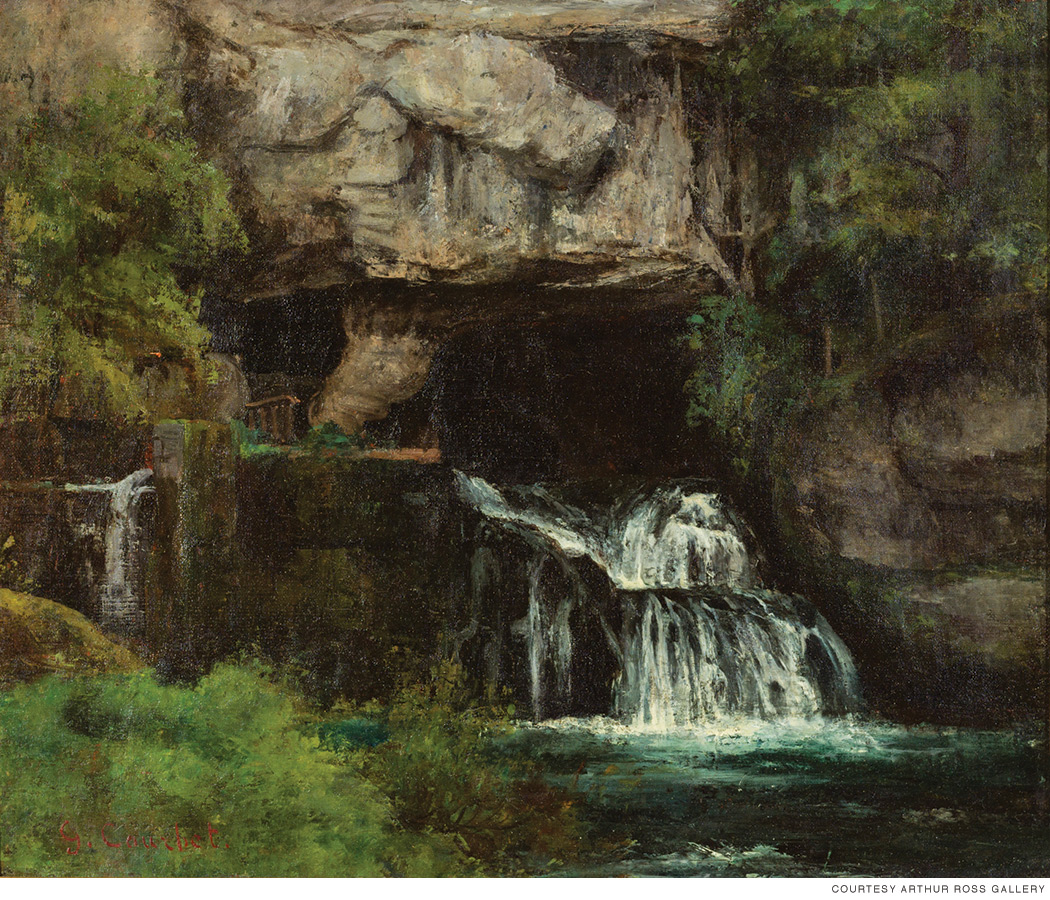

She sorted through the calling cards—mostly royalty and former clients of Evans, who had cultivated a relationship with French Emperor Napoleon III—and pulled out a small, unframed canvas that was virtually black with age. “I couldn’t figure out what the image was because the varnish was so darkened,” Marsden-Atlass recalls. “But in the lower left-hand corner you could make out three letters of a signature that I happened to recognize.” Marsden-Atlass had spent 10 years teaching 19th-century art in Paris, but this was still a bit of a mystery, so she sent the canvas to renowned conservator Barbara Ventresco. Once cleaned, the painting was still dark—but with the moody intent of its creator rather than decades of age and neglect. It revealed a waterfall spilling out of a murky cavity in a foreboding limestone wall, and it was signed G. Courbet.

That would be Gustave Courbet, who led the Realism movement in 19th-century French painting and is seen as something of a hinge between the salon-endorsed Historicism of the early 1800s and the Impressionists who followed in his plein air footsteps.

It took a few more years, but in 2022 a panel of experts representing the Institut Gustave Courbet in Ornans, France, formally authenticated the painting as an 1864 depiction of the source of the Lison River in eastern France, near the artist’s birthplace. The canvas was also listed in the final inventory of Evans’s Paris home upon the dentist’s 1897 death. It is now the centerpiece of an exhibition that runs at the Arthur Ross Gallery through May 28. At the Source: A Courbet Landscape Rediscovered offers a focused consideration of the artist’s later-life landscape work, which is often overshadowed by the forthrightly political and convention-busting figurative paintings of peasants and laborers that first won him recognition at the century’s midpoint.

The newly discovered painting shares the walls with three borrowed Courbet landscapes—including a larger-scale depiction of the Source of the Lison from a private Minnesota collection—plus a canvas by an unknown imitator of Courbet that’s one of two pieces on loan from the Philadelphia Museum of Art. A small assortment of postcards and books, including an 1825 tourist guide that outlines an itinerary for visiting the Lison’s waterfall and grotto, helps provide some social and economic context for the currents of thought that come together in the focal Courbet painting.

André Dombrowski, the Frances Shapiro-Weitzenhoffer Associate Professor of 19th Century European Art who co-curated the exhibition with Marsden-Atlass, calls it an “innovative landscape depiction” that “messes interestingly” with the traditional approach to the genre, whose sky-filled compositions typically drew viewers’ eyes into a distance whose bright boundlessness suggested a “potentially redemptive future.” The Source of the Lison exemplifies the way Courbet’s landscapes broke from tradition.

“They are really dark, quite remote,” Dombrowski says. “They tease our eyes not into the distance but into caves, and sources of water—and thereby both attract and trap the viewer, quite literally. It’s a landscape painting that wants to stick your nose more into the here and now of the immediate world, rather than any fictions of distance and destiny.”

The Lison’s source was “enmeshed” in a growing ambivalence about industrialization’s impact on picturesque natural settings, Dombrowski notes. Its tumbling water had been harnessed by a mill that hugged one riverbank—as shown by one of the exhibit’s postcards. Salt mining was also prominent in the area, which Courbet knew intimately from his youth. In the context of such industrial intrusions, Courbet’s “landscapes are often made out to be one of the sites in which an environmental consciousness develops in painting.”

Yet the painter’s commentary on such sites was oblique. He took care to leave the Lison’s mill outside of the frame, for instance—recording only a wooden railing that had been installed for the benefit of nature tourists.

“Courbet wants to construct a modern landscape that’s in tune with the overall pleasures that landscape painting provides,” Dombrowski explains. “Who wants an industrial site over there? He wants to sell and market these, so their tourist appeal needs to be front and center.” Instead, Dombrowski suggests that the painter “transposed” the unease into a “deeply claustrophobic” rendering of the site.

“He doesn’t create a comfortable entry into the landscape, but actually a rather haunting and dark and mysterious form of landscape representation, that I think he feels is a little bit closer to a modern, changing landscape that entirely refuses the industrial complexes within it,” the professor muses. “He’s not literally showing [the industrial aspect], he’s just making the landscape a bit more of a damaged, moodier, darker entity.”

Courbet’s technique, meanwhile, typified an “early modernist impulse” to deliberately emphasize “the relationship of the material world and the materials of painting,” says Dombrowski. Scenes rich in water, rocks, and moist undergrowth provided him with an opportunity to reflect these aspects via the “viscosity of the paint in which he renders them.” In subsequent decades, Impressionist painters would take further steps toward drawing attention explicitly to paint itself in their depictions of outdoor scenes.

Yet the curators hope viewers will encounter this rediscovered work (whose permanent campus home is still being determined) on its own terms. “There isn’t really a painting like it on campus, or in Philadelphia,” says Dombrowski. “It shows the ways 19th-century painting prefigured forms of environmental consciousness that we are today so focused on.”

In conjunction with the exhibit, Penn Press has published a richly illustrated catalogue featuring scholarly essays considering the painting from angles ranging from the site’s geology and industrial development, to its development as a tourist attraction, to Courbet’s landscape oeuvre and talent for self-promotion, to the “gilded life” of Thomas Evans.

The circumstances under which Evans acquired (or was given) this painting remain obscure. One hypothesis, says Marsden-Atlass, hinges on his acquaintance with Napoleon III’s wife Eugénie de Montijo, who was known to have purchased Courbet works through an intermediary. “Maybe he followed suit,” she speculates.

The Source of the Lison’s decades-long relegation to a box in the Evans Building’s basement is likewise open to multiple interpretations.

“I think it disappeared because it got tarnished and dirty and it probably needed some care for which probably there were no funds,” says Dombrowski. But the professor’s puckish side wonders if someone in Penn Dental’s past was just unsettled by the dank grotto itself: “I can’t help but think that an institution that fights tooth decay couldn’t quite handle the cavity it represents.” —TP