Class of ’94 | One day in the winter of 2010, Norman Golightly W’94 found himself in the passenger seat of a 1982 Toyota Corolla, barreling down a muddy road in a village outside Nairobi, desperately searching for a cow.

As raindrops pummeled the windshield, he was struck by the thought that less than one year before, he’d been producing a $150 million Hollywood movie. Now he was hunting down a barn animal as though his life depended on it.

As he held on to the dashboard for dear life he thought: “Damn. Life is pretty amazing.”

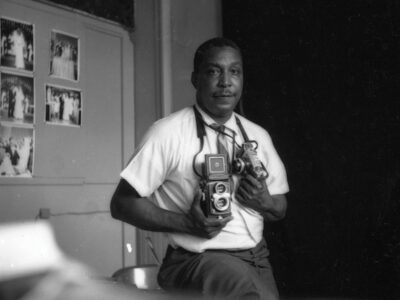

Golightly was, for more than a decade, Nicolas Cage’s producing partner in Cage’s Saturn Films. He produced more than a dozen films, including blockbusters like Ghost Rider and critically acclaimed movies like World Trade Center and Lord of War.

When the company folded for financial reasons in September 2009, Golightly found himself in the throes of an existential crisis.

“My whole life had been breakfast meetings, lunch meetings, dinner meetings, with meetings in between; 1,000 phone calls a day, 1,000 emails a day, and traveling the world to make films,” he recalls. “So when the phone stops ringing, no matter how mentally prepared you are for it, it’s pretty jarring. The silence was deafening.”

He decided to go halfway around the world to help some kids.

“I wanted to get my hands dirty in someone else’s problems,” says Golightly, now 39.

Through Amy Eldon, the wife of director Jon Turteltaub (The Sorcerer’s Apprentice), Golightly had heard about Cura, an orphanage 30 miles outside of Nairobi that’s home to 50 kids who’ve lost their parents to AIDS. Eldon, who was raised in Kenya and whose father helped found the orphanage, admits to being surprised by Golightly’s interest.

“I remember thinking Norm was this Hollywood guy—I figured he would last for five minutes,” she recalls. “I thought, ‘What is he gonna do with the kids, teach them script development?’”

Golightly, an avid amateur photographer, wanted to teach the children photography. So he started a Facebook page called Kenya Spare a Camera and gathered 25 used cameras from friends. A few weeks later he was on a plane to Africa.

“I definitely had a What have I done? moment on the plane over,” he says. After all, he’d been on the set of Sorcerer’s Apprentice just months before, sitting in a director’s chair with his name on the back.

But the minute he drove onto the Cura property, and 50 kids with huge smiles on their faces began jumping on him, on the car, and on each other, that thought fled faster than a gazelle.

“There was just a feeling of love and warmth and welcoming,” he says. “I knew I’d made the right decision.”

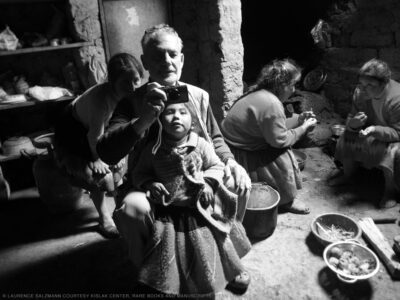

Soon Golightly was immersed in the orphans’ lives; taking them on long walks, reading to them, and teaching them how to use the cameras—which, for many, was the first time they’d seen their own appearance.

“Mirrors are not commonplace in this area, so the presence of cameras opened up a world of both identity and self-expression,” he says.

Golightly posted the photos the children took on his Kenya Spare a Camera page—the perfect marketing tool to interest friends back home in his work abroad.

On a tour of the premises one day, the house manager, Moses, showed him a barn and chicken coop. When Golightly asked why both were empty, he was told there was no money for animals. Through Kenya Spare a Camera, he began to raise funds. He bought 200 baby chicks from a nearby farm—a boost to both the menu and the income of the orphanage (they sell the extra eggs at market). Many of the kids had never eaten eggs before.

A week or so later, he told Moses he had raised $1,200 and was ready to start cow shopping. Moses was stupefied.

“Things don’t really work that way in Africa,” says Golightly. “Something like buying a cow could take six months.”

Which is how he found himself on a muddy back road, heading to a rural African village, overseeing the purchase of a dairy cow with the intensity he brought to 12 years of movie-making. He had seen 20 cows already, none of them right. He’d already told the kids they were getting a new cow. Moses was sure Golightly wouldn’t come through.

“I told him I wasn’t leaving until I had the cow,” Golightly says, and sure enough, the day before his departure, he found a pregnant dairy cow for the right price. The children christened the cow—despite its gender—Norman.

Amy Eldon’s father, Mike, says he was as surprised as his daughter by “Mr. Hollywood parachuting into rural Africa,” as he put it. But instead, he says, Norm “came with deep humility and a great desire to make a big and lasting difference. Which he certainly has.”

Last May, Golightly returned to the orphanage and raised over $20,000 through his new website (www.kenyaspareacamera.com)—enough to cover expenses for 23 children to stay at Cura for a year.

“After living with these children for a month now on two separate occasions, parting ways is painful for both sides,” he says. “If there’s a silver lining to that parting, the kids have gone from asking me ‘Will you come back?’ to ‘When will you come back?’”

His trips to Africa have given Golightly a different perspective. He doesn’t want to go back to making the kind of films he once did. He’s planning to start a film-production company dedicated to making socially relevant movies that will “educate people and empower them to effect change.”

“That’s what happens when you go to Africa,” says Turteltaub. “You get affected in a fulfilling way. It’s not what you see that’s awful that makes you change; it’s what you see that’s beautiful that makes you change. Norm’s become addicted to having a deeper life.”

—Stefanie Cohen C’97