Amanda Shulman C’15 has earned national acclaim with Her Place Supper Club, where she’s also bending stubborn industry standards around life balance and labor compensation. It all began with a jolt to Penn’s off-campus social scene.

By Trey Popp | Photography by Michael Branscom

Amanda Shulman C’15 liked to drop the Facebook post right into the lull between lunch and afternoon classes, when she knew her undergraduate peers would be itching for an online distraction.

ATTENTION! It’s that time again. I’m hosting a four-course dinner this Friday at 8pm. $35 a head and BYOB. Good food and good company are guaranteed! Prepare to eat a lot and make new friends. Message me if interested—space is limited and vegetarians not welcome (SORRY!).

As her inbox started pinging, she’d turn off her phone. It was more fun to let the messages pile up and check them all at once. Besides, she had classes of her own. The political science major might have sweated through the previous night perfecting an almond and olive oil shortbread crust to carry a ganache-glossed chocolate mousse, but there was no escaping the syllabus.

Of course once the invitation was out in the wild, it was hard not to obsess over how to time her focaccia’s second rise, or whether to spice the squash ravioli with cinnamon. But the secret ingredient was the guest list itself. The ideal Amanda Shulman dinner party would feature a dozen people who knew each other little, if at all. With any luck, at least one of them would be a total stranger to the chef herself. “I love when that happens,” she wrote in an essay for the Gazette during her senior year [“Notes from the Undergrad,” Mar|Apr 2015].

She had emailed me, cold, to pitch that idea the previous November, introducing herself as a student of Rick Nichols. Nichols, who is perhaps now best known for the room named in his honor at Philadelphia’s Reading Terminal Market, spent the second half of his 33-year Philadelphia Inquirer career chronicling local food culture with a blend of depth, discernment, and contagious capacity for delight that won him the rarest reward in journalism: genuine affection. After retiring in 2011 he taught a food-writing seminar at Penn. Since I was moonlighting as Philadelphia magazine’s restaurant critic at the time, Rick would sometimes invite me to talk to his class. But we didn’t do it that particular semester, so Amanda contacted me without the nerve-settling benefit of a prior connection.

I helped her with her essay—but it didn’t need much help, so the editing process played out over email in the space of a few weeks. We never met in person. And regretfully, I never tried to wrangle an invitation to dinner.

Shulman graduated that spring. Three months later I wrote my final restaurant column. Nine years and roughly 300 reviews had brought me to my expiration date. Hungrier for live music or theater—and bereft of an expense account—I all but stopped eating out. The last thing I wanted to read was other people’s restaurant reviews, so I lost touch with the Philadelphia dining scene. Life chugged along just fine in the absence of lavender foam, cacio e pepe gelato, and the latest hot chef’s “play” on scrapple. And like Frederick the Field Mouse, I’d stored up enough memories of the soulful cooking I’d liked best to sustain my own efforts in the kitchen. Within four years I had achieved complete uselessness to friends seeking restaurant tips. Then the pandemic dropped a curtain over the whole shebang.

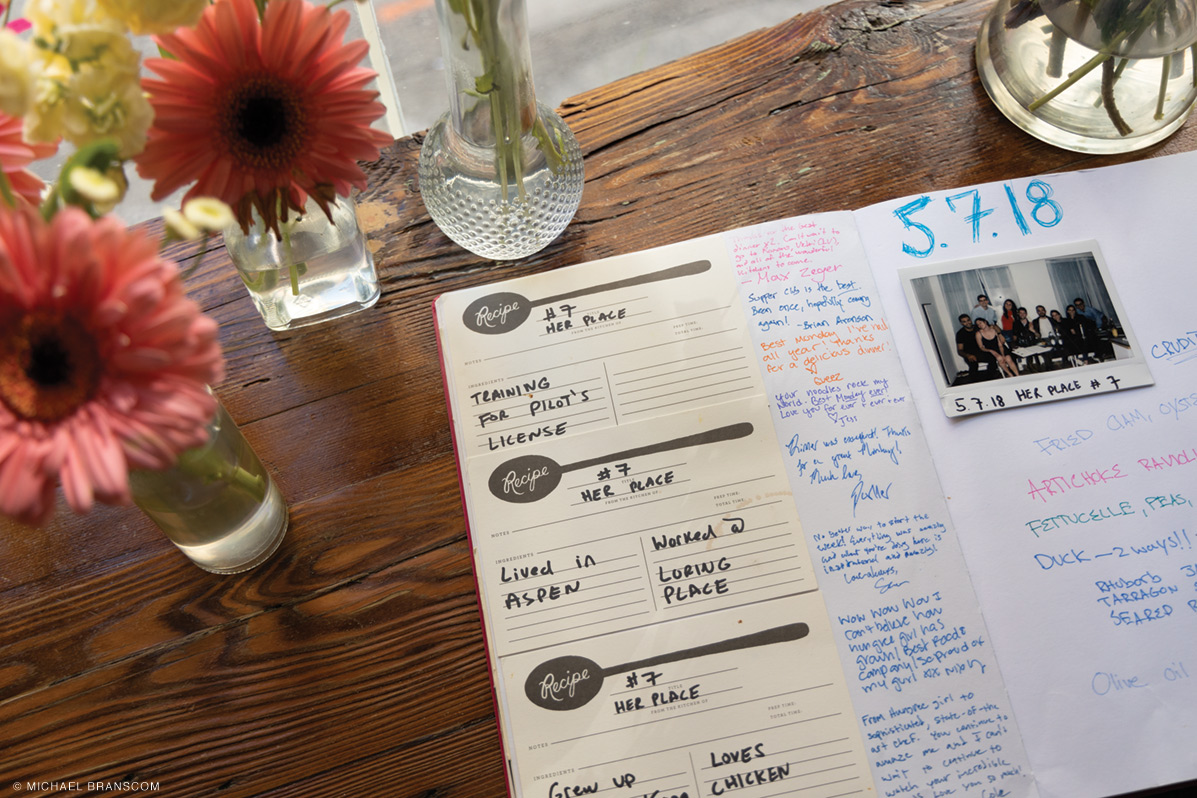

By the summer of 2023 I was the one casting around for recommendations, and people kept pointing me toward a spot called Her Place Supper Club. It had begun as a pop-up in a narrow Sansom Street storefront I’d known as a source of pizza by the slice. Seating 24 people for a fixed four-course menu that changed every two weeks, it had a dinner-party vibe and released prepaid online reservations every other Sunday that sold out in a blink. By the time I realized it was run by the same young woman who’d written that essay for me eight years before, the James Beard Foundation had named Amanda Shulman a national finalist for its Emerging Chef award.

Food and cooking were on Amanda’s brain from the moment she set foot on Penn’s campus. Both loomed large over her childhood in Greenwich, Connecticut, where she often helped her mother prepare family dinners and loved gathering around the table to celebrate Jewish holidays. By senior year of high school she was running a recipe blog. On September 4, 2011—two days before Convocation, in the thick of New Student Orientation—she posted an approachable stab at shellfish paella cooked in chicken broth.

Then her Tumblr went silent until Thanksgiving. Penn was great, but the problem with living on campus was that there was nowhere to cook. Over winter break she attacked her home kitchen with a vengeance—chicken cacciatore, chocolate golden layer cake, bucatini and meatballs, a “kinda sorta” Lyonnaise salad. Then, during second semester, she hit on a hack: older friends in off-campus apartments.

“That was the big thing freshman year,” recalled her friend Sara Adler C’15. “We would have these late-night gatherings where Amanda would cook—and kind of invite random people that we were out with. It always turned into a funny, random night: Amanda’s late-night food with people that you just met.”

For folks who happened to be in the right place at the right time, the spring semester was slicked in butter and slathered with cream. Whoopie pies. Banana Nutella bread pudding. Carrot cake cupcakes frosted with rum honey cream cheese. “Slutty Brownies.” Nicole Ripka C’15 remembered her first taste of a chocolate chip cookie on one of those nights. “I took a bite, and I was like—well, I don’t think you can quote a curse,” she told me. “But that cookie was the origin moment. Beyond delicious.”

The real turning point came sophomore year when Amanda moved into a house at 41st and Irving Streets. Her housemates barely cooked, so she had the run of the kitchen. She memorialized her first dinner—a collaboration with her friend Cole Stern W’15—soon after moving in. Gradually a format took root. What started out as casual group meals morphed into a deliberate “social experiment.” Amanda didn’t just want to cook for her housemates, or her sorority sisters, or any one club or group.

“It needed to have more depth,” she recollected while stacking fried eggplant slices and tomato butter into an eight-layer terrine one Friday afternoon at Her Place in July. “And on a campus of thousands of people, it just seemed exciting and fun and special to bring people from different walks of life, and all my different social circles, into one room, and have a shared experience.”

For Nicole Ripka, who lived with her, it was a 180-degree turn from the “standard school socializing” that governed undergraduate life. “I would come home to our house and there would be people I’d never seen before in our dining room,” she recalled. “What Amanda was doing was so different from anything else on campus. She was famous for these dinner parties. Everyone wanted to be around her—she created such an amazing and unique atmosphere for a college campus. This became like the hottest ticket in town.”

The meals seemed to scratch an itch, especially among upperclassmen chafing against the cliques that compressed their social horizons. “It’s really challenging to break out of a routine you’ve fallen into, or a scene you’ve fallen into,” Ripka reflected. “This was just a really organic, breakout moment. I think also that as we grew up in college, there was such a craving for this—people were evolving and wanted to spend time with different people. And this was a vehicle for that.”

If Amanda’s social mission outstripped her culinary ambitions at first, that changed after she returned from a semester in Rome during fall of her junior year. Meals veered away from steak, salad, and mac-and-cheese, toward productions like a menu featuring the four classic Roman pastas: alla gricia, carbonara, cacio e pepe, and amatriciana. The signal event came when she hoofed across town to Esposito’s Meats in the Italian Market and hauled back a 20-pound suckling pig. She’d never cooked one before and wanted practice breaking the whole animal down. There was just one problem: “I couldn’t keep it in my house,” she recalled, “because I lived with six women who would have freaked out if there was a whole pig in our fridge.”

So she stashed it in the basement fridge of the Theos fraternity house, crossing her fingers that a friend there would manage to shield it from hijinks. “I was so nervous they were going to do something weird during a party, and make a pledge eat it.” But the boys behaved themselves, and Amanda served 10 people five courses of pork, from high on the hog to low.

Plainly she was no longer the kind of chef content to pry open a can of chicken broth for a shellfish paella. You could count on her to make a proper fish fumet.

In 2014 Amanda won the Terry B. Heled Travel & Research Grant, an endowed fund at the Kelly Writers House that gave her $2,500 that she used to shadow a truffle hunter in Umbria, Italy, and learn regional techniques for preparing black truffles. “My truffle hunter was so hot,” she later told the Daily Pennsylvanian’s 34th Street magazine. “My dad had this fear that I was going to marry him. It was the running joke among my family that Amanda will never come back to visit because the truffle hunter doesn’t have a passport.”

But she did return, wrote a paper, and delivered a presentation at Kelly Writers House culminating in a demonstration of hand-cranked pasta that she cooked for everyone there.

She exuded a different sort of confidence now. As a freshman she’d branded her “Hungree Girl” blog with a winking sort of bravado. “All I want in life is to be on the Food Network and have my own show,” she declared, “so if ya like me, keep following because I’m gonna be big.” When 34th Street featured her in its Ego of the Week column in February of her senior year, her sense of humor was still playful but her ambitions had matured. Asked where she saw herself in 10 years, she replied, “I will have my own restaurant. I’m not sure where yet.” She then deftly took some air out of her own balloon by conjuring an improbably idyllic farm-to-table future complete with whimsical goat-milking. But her intentions were clear.

They’d been bolstered by her experience working in a pair of Center City kitchens, a development for which she credits Rick Nichols. For a profile-writing assignment he suggested that she interview Sal Vetri, the father of renowned Philadelphia chef Marc Vetri. Rick and Sal were friendly, so Rick set up a meeting at Amis, an overachieving Roman-style trattoria Marc had opened in 2010.

“The interview was supposed to be about his life,” Amanda recalled, “and I got there and he was like, ‘Okay, let’s cook family meal together for everybody.’” So Sal put her to work making the staff dinner. Three hours later, before walking out the door, she asked head chef Brad Spence if she could come back and work for free. Unpaid apprenticeships remain a fixture of the restaurant industry. Soon she was putting in one or two shifts a week from 2 p.m. until about 10 p.m.—plus two mornings a week at the Bakeshop on 20th, also “paid in knowledge,” from 7:30 a.m. until noon.

“Junior year was a little tough, second semester,” she allowed. “But senior year I was a part-time student. I finished early, so I got to use my time doing that.”

Senior year had a nervous edge, though, especially as on-campus recruiting ramped up toward graduation. People don’t come to Penn to cook for living. “In our house,” Nicole Ripka told me, “four of the girls went to work at Goldman Sachs. One of them went to BlackRock. … Amanda had a different path from everyone else that was around her. Which I think was really hard, probably. But that was just her. She felt this relentless calling to do something. And whatever she did—whatever it was, whatever she put her mind to—she just crushed it. She’s the hardest worker I know.”

She was also fixing to be the least paid. As Amanda surveyed the prospects that lay beyond Commencement, she didn’t kid herself. “I’m going to graduate with no job,” she thought, “because restaurants hire on a day-of-need basis. And I have to explain this to all my friends and everything. … It almost felt easier to get a job on Wall Street or go to business school—which is hilarious—because that’s what I was surrounded by. But I was—I am—so stubborn. And I was pretty committed at that point.”

She hoped to land a full-time position at Amis, but they didn’t need anybody. Her luck turned when an opening cropped up a few blocks away at Vetri Cucina, the titular chef’s flagship, which belongs on any shortlist of the best Italian restaurants in North America. She landed that gig, cooked for an actual paycheck for two years, and then hit the road. After returning to Italy for a four-month stage in Bergamo, where she worked in exchange for room and board, she pinged to New York, where she did stints at Momofuku Ko and Roman’s and revived her dinner parties in the off hours. Then she ponged back to Marc Vetri, who hired her to be the opening executive sous chef at his new location in Las Vegas. There she met some of the folks behind Joe Beef, a lauded French restaurant in Montreal that became her next stop.

Moving to Quebec proved hugely influential. It immersed Amanda in French technique, pushing her beyond her Italian comfort zone. And it allowed her to rejoin her boyfriend Alex Kemp, with whom she’d cooked at Momofuku Ko. She spent about a year in Montreal before pandemic restrictions pulverized fine dining. The couple moved to Philadelphia in September 2020.

The pandemic had also done a number on Philly’s food scene. Although city officials had lifted the suspension on indoor dining by the time Amanda returned, they were still restricting restaurants to 25 percent of their seating capacity while capping table sizes at four people from the same household. Some restaurateurs had supercharged their sales through a booming takeout trade, while others limped along hoping for normality to return. Amid that volatile mix of fear and opportunism, Amanda found herself shopping for restaurant space in a schizophrenic real-estate market. She’d lined up investors but lease deals kept falling through.

After about six months of frustration, she noticed that the old Slice Pizza storefront was shuttered. She approached building owner (and then-Philadelphia City Council member) Allan Domb with a proposal for a summertime carryout picnic-basket pop-up. “Give me a stove, a deep fryer, and three fridges,” she told him, “and I’ll pay you rent for two months.” Domb agreed. Then, the week before she was set to open, the city lifted all dining restrictions.

That changed everything. “Picnic baskets are expensive,” Amanda thought. “It’s going to be way easier to just cook dinner.” So she rolled the dice, sinking $15,000—“all of my savings”—into a supper club. Without financial backers, and blessed with the stakes-lowering lightness of a two-month lease, she could do everything her way. A few days before the first dinner service, she described Her Place to the Inquirer as a “not-restaurant.”

Two years later I finally got a chance to join the party, which has been hopping at least since Philadelphia magazine tapped Her Place as the city’s best new eatery in 2022. (The Gazette paid, but Amanda set aside an all-but-impossible Friday night reservation.) Flowers bloomed in the storefront window and circled the lips of mismatched porcelain plates—some gilded, others plain—that bore the ripe delights of late July. Boquerones on pesto-smeared challah toasts launched an opening medley that culminated in skewers of batter-fried skate cheeks and tangy zucchini escabeche served with a clam-mayo remoulade. Those savory bookends framed a sweet stone-fruit interlude that found plum segments showered with hazelnuts, draped with ruffled shavings of funky and nutty Tête de Moine cheese, and dressed with the previous summer’s nectarine jam. Tomatoes came out, both oven-blistered and fresh, while Amanda and her sous chefs began searing thick pork chops in cast iron skillets.

As a trio of servers uncorked bottles from a smartly curated, Eurocentric wine list—and struggled a bit to keep up with cocktail orders in the absence of a dedicated bartender—Amanda welcomed everyone and beckoned her guests to do the same. “Whether you’re here on a date or catching up with friends, introduce yourself to the people at the next table over,” she said. “It’s our one rule.”

The room fluttered with waving palms and clinking glasses before patrons naturally swiveled back to their twosomes and foursomes. Though Amanda has occasionally joined the tables into common rows, harkening back to the old parties in West Philly and New York, Her Place has the intimacy that’s built into any restaurant that books most guests by the pair. When she was hosting in her house, the guest list always loomed large. “You’re always nervous: Are these people going to get along? Is that person too extra? Are they going to vibe with this?” The dynamic is similar here, she told me—just less predictable. “The room has an energy every single night. And sometimes we’re like, ‘Oh, these people were not looking to go out—everyone wanted a quiet date night.’ And it’s just different.”

So a lot of Her Place’s conviviality comes from, well, Her. Amanda occasionally sallied out from the open kitchen to banter with a familiar face, but more often raised her voice from the prep counter, embracing the whole room. She enthused about the soft-shell crabs they’d snagged as an optional add-on, done up like Nashville hot chicken with what she half-deprecated as a cheat-code sauce: pickled ramp juice, browned butter, and Frank’s RedHot. She teased some new dishes that would roll out on Monday after we ate the last iteration of this menu that would ever be served. Then bowls of corn ravioli arrived at our place settings, under a scattering of button chanterelles that lent a woodsy depth to the purity and directness of the pasta filling.

That dish, along with the plum salad and a mille-feuille dessert whose featherweight pastry sheets held peaches three ways—fresh, poached in stone-fruit broth, and a puree of last summer’s preserves—exemplified what I liked best about Amanda’s cooking. Her flavors are layered but focused. They proceed from the season. Her technique calls attention to the food, not the other way around. There’s little of the postmodern masquerade or deconstructivism that typified tasting menus during my restaurant-critic days, when the visual dictates of Instagram seemed to prolong the whizbang trickery that was already sputtering out at El Bulli. Amanda’s plating is pretty in the way of an elevated family dinner, not a social media post reaching to go viral. Nothing at Her Place is designed to “provoke discomfort, conversation, and awareness,” as an owner of Chicago’s Alinea described a canapé shaped like the SARS-CoV-2 virus served outdoors at the height of the pandemic.

“I like fancy food. I like touchy food,” she told me. “I like making things complicated—but when you eat it, it doesn’t taste complicated.” She mused for a moment. “That’s how I would describe our food: fake simple. You eat it and it tastes simple. I don’t want you to eat something and wonder, ‘What’s going on here?’ No. I want you to taste something and go, ‘Wow, this corn ravioli really just tastes like corn!” She might add gelatin to the filling she pipes in, to approximate the gush of a Shanghai soup dumpling. But “people don’t need to know all the behind-the-scenes stuff,” she said. If the last couple decades have been a heyday of conspicuously clever, overexplained culinary confections, she’s shooting for “anti-fine dining.”

No restaurant can recapture the spirit of the Penn-era dinners that launched her on this path. “That moment in time will never be replicated,” she said. “Because it was so organic. There was just nothing to lose—it was $30 for people to come and eat. That’s what you’re spending on a pizza and a salad at Allegro anyways. So the stakes were low and it was so fun.”

The stakes are higher at a Rittenhouse address where dinner now starts at $90 a head (which, to be fair, counts as unusually accessible in the realm of chef-driven ateliers, albeit not the steal it was two years ago at $65). And the work leaves no place to hide. “It’s like a performance,” she conceded. “You’re on display, which is hard sometimes.” But she reckons that in the last two years there have been maybe seven nights where she didn’t want to play the part. That’s not a bad ratio. And the upside matters a lot more to her. “After cooking for 10 years in a basement or behind a door, it’s nice to be able to connect with who you’re feeding. Because it makes it much more enjoyable, and full circle, when you can talk to somebody about what you did all day.”

My favorite passage of the essay Amanda wrote for this magazine started with her reeking so badly of garlic that she could barely stand to inhale her own aroma. “I abandon the kitchen to jump in the shower,” she wrote. “I ditch the apron that’s been glued to my body for the past two days in exchange for my ‘I’m a hostess and I just threw this little gathering together!’ outfit.”

I don’t know how often I manage to pull off that trick when I cook for company. I’m sure my outfits could use improvement. But my mother was, and is, an absolute natural. It’s a lovely grace to savor in someone’s home. And rarer to find in a restaurant: unfussy excellence that doesn’t take itself too seriously, neither pretentious nor too precious, just genuine and warm.

One truth about fine dining is that it’s hard to smile every minute when everyone from the boss on down is being worked to the bone. Whether the kitchen is a stage or hidden from view, it’s a site of cuts and burns, stress and fumes, sweat and bruises and grease traps that need emptying, and scapegoats for servers who just got stiffed on a tip. Sometimes the resulting camaraderie wins out, and some nights it doesn’t. Amanda has tried to tilt the balance at Her Place by drawing what is probably the rarest line in the restaurant business: no weekend service.

“Opening Monday through Friday is amazing. It offers life consistency.” She’s at that age when all her friends are having weddings—and Amanda married Alex Kemp in August. “I don’t have to take time off to go. I can go to my siblings’ children’s birthday parties, and holidays,” she said. A set menu for a predictable headcount helps to balance the books. Saturday nights typically juice a restaurant’s bottom line with extra alcohol sales. “But between $500 more on a Saturday night and getting to have all Saturdays off, I’m very happy to miss out on that.” Ditto for Sunday brunch.

She also closes the restaurant altogether three weeks per year—and, in a further departure from standard industry practice, pays her 10-person staff a vacation stipend. “I’ve worked in places that are seemingly great,” she explained, “where you’re like, ‘Great, I get two weeks off!’ And then you have no money in your bank account at the end of vacation because you didn’t work that week, and it feels like a trick. So we do paid vacations. And we are significantly higher than the average line cook and sous chef salary.”

Her Place also covers 50 percent of employees’ health-insurance premiums. That’s another sore point in a sector where a 2019 survey found that fewer than a third of restaurants offer any kind of healthcare plan—though the tight post-pandemic labor market may be spurring more in that direction, to attract and retain staff. “That’s not enough,” Amanda says, “when I look at my friends in their corporate jobs, and the benefits they get.” But in the context of a regulatory and tax system that can almost seem custom-made to thwart small restaurants from offering health coverage, it’s a meaningful improvement on the status quo.

The chef essentially wants to make her chosen field more sustainable for the people who are drawn to it. “I want this to be something that’s not just a stop in people’s trajectory,” she told me, “but more like it could be a career.”

She’ll see soon enough. It so happened that right as I finally caught up to Amanda, she was in the midst of doubling down. Not long before they got married, she and Kemp opened another restaurant. My Loup, a French-Canadian bistro that seats more than 50 people, including 10 at a proper bar, lies a few blocks away from Her Place, on Walnut Street. It’s Alex’s “baby,” but Amanda darts back and forth between kitchens as a full partner and chef. The couple is following the same Monday-to-Friday schedule and staffing practices as Her Place, but with an a la carte menu and at twice the scale.

Only time will tell if they can sustain it, but My Loup could hardly have asked for a sweeter honeymoon. On the first Tuesday of September, the Inquirer published a rave by longtime restaurant critic Craig LaBan, who called it “the perfect reply for those who crave more access to Shulman’s delicious universe.” One week later, Food & Wine magazine followed the James Beard Foundation’s lead by tapping Amanda as one of its Best New Chefs. And the Tuesday after that, the New York Times named My Loup as one of the “50 restaurants that excite us most right now.”

Hopefully it won’t take me another eight years to lock down a table.

What a wonderful, heart warming article. I am very happy for this ambitious young chef, Amanda. Perhaps, next summer when my son graduates from UPenn, we might be able to get a seat at the table.