The Penn Women’s Center celebrates five decades of providing advocacy, advising, refuge, counseling, company, and tea. From its origins in the struggle against campus sexual violence, the center has evolved to tackle a range of concerns, from wellness to combating racism. The latest debate: Is its name, meant to be welcoming, too restrictive or exclusionary at a time when gender itself is contested?

By Julia M. Klein | Illustration by Melinda Beck

Sidebar | Changing Names, Broadening Focus, Continuing Challenges

On a mild late-summer afternoon, soon after the semester’s start, a purple-and-white banner announcing an open house is attracting both the avid and the merely curious.

“I’m a woman. I like to be in spaces where other women support each other, and that’s obvious when you see the words ‘Women’s Center,’” says Leigh Monistere GrEd’28, a first-year student at the Graduate School of Education. The founder of a literacy nonprofit, she is among a stream of students investigating the Penn Women’s Center, housed in the former Theta Xi fraternity house at the corner of Locust Walk and 37th Street.

On the porch, visitors snag free T-shirts celebrating the center’s 50th anniversary and proclaiming, “Growth. Action. Solidarity.” Inside, they crowd around a table to iron decorative decals onto pouches with the center’s logo.

There’s free food, too: chocolate-covered pretzels in the living room, cheese and fruit in the eco-kitchen, with its energy-efficient appliances, cork floors, and cabinets of reclaimed wood. In the backyard garden students chat with Women’s Center staff over lavender lemonade and iced English breakfast tea. On the patio are chiseled quotes by women writers and other icons of feminism and civil rights. From Alice Walker, author of The Color Purple, comes this gentle observation: “In search of my mother’s garden, I found my own.”

Since 1973, the year of its founding, the Penn Women’s Center—which relocated in 1996 from Houston Hall—has been a refuge, gathering place, and resource center for the Penn community, including faculty and staff: women mostly, but also sexual minorities and the gender nonconforming, and sometimes their straight male allies.

“The Penn Women’s Center was also a home for young gay or LGBT students,” says Daren Wade C’88 SW’94, now associate director of career development at the University of Washington’s School of Public Health. “It was very much a place that I felt like I could be myself.”

Mika Rao C’96, who was president of the South Asia Society at Penn, says she relied on the Women’s Center to help a friend with financial problems stay in school. When members of the South Asia Society faced an incident of racial intimidation, “the first thought I had was, ‘Let’s call the Penn Women’s Center,’” says Rao, now managing director of williamsworks, a philanthropy consulting firm. “What I found was that the Women’s Center was just there to support women, period, and [help them] navigate a very large, complex university system.”

Born out of concerns about sexual violence, the center also has provided a locale for a meeting or hangout, a cup of tea, career advice, quiet study, or confidential counseling. Programming over the years has tackled the nuts-and-bolts feminist issues of sexual harassment, pay equity, and reproductive rights, but also wellness and carpentry skills. The center has been at the nexus of University-wide struggles to better the status of both women and minorities, helping to spawn a range of affinity and activist groups. It was intersectional and anti-racist long before the terms became buzzwords.

But much of its agenda wasn’t explicitly political. In recent years, new mothers—including the center’s current director, Elisa C. Foster—could avail themselves of a lactation center. A small crafts room provides yarn, fabric, and a sewing machine. Along with feminist classics, the library offers poetry by Anne Sexton, Jeffrey Eugenides’ novel Middlesex, and the stories of Gertrude Stein. A 2017 volume titled Crafting the Resistance: 35 Projects for Craftivists, Protestors, and Women Who Persist has helped inspire center programming, Foster says.

The Women’s Center’s conference room is temporarily overflowing with stacks of newspaper articles and other documents. In honor of the anniversary, Foster is assembling an archival display that will debut during Homecoming Weekend. Spring semester events will include a joint symposium with the Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies Program [see sidebar] and a May 18 celebration during Alumni Weekend.

The yearlong anniversary also will be an occasion for the Women’s Center to reevaluate its mission—and its name. “Nationally, at universities across the country, their Women’s Centers are changing their names to Gender Equity Centers,” says Foster. “We hear it from the students, we hear from the community that we serve, we hear it from the national trends.” A name change isn’t happening this year, but “it’s not off the table,” Foster says.

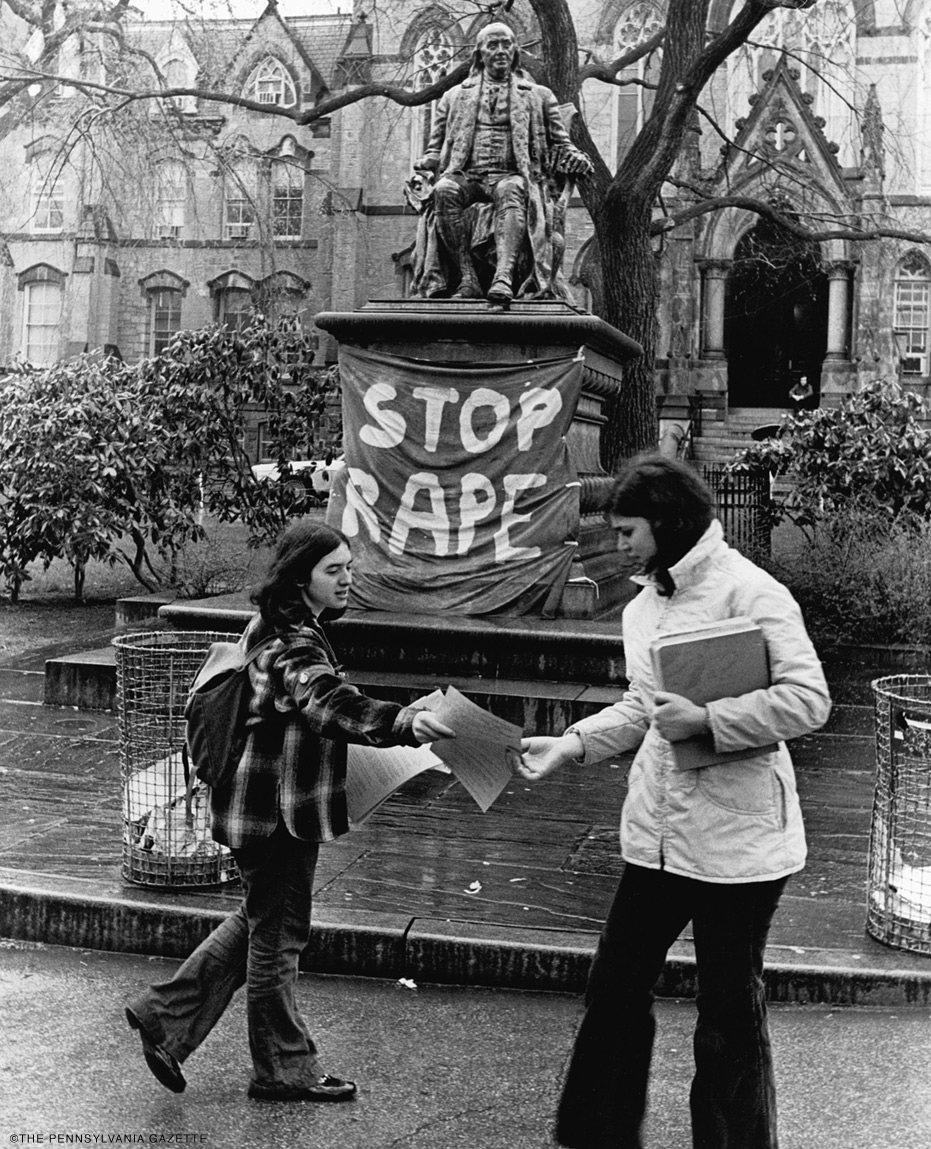

The second-wave feminism of the 1970s helped spawn women’s centers at universities and colleges nationwide. At Penn, the specific trigger was the gang rape of two nursing students at 34th and Chestnut Streets.

The assault upset and frightened Penn women. But the real flashpoint may have been the tone-deaf reaction of Penn’s director of public safety. In a meeting, he suggested that it would help if female students refrained from wearing provocative clothing. The response, from Rose M. Weber CW’75 L’96, now a civil-rights attorney in New York, seems mythic: “I can walk buck naked down Locust Walk, and it’s your job to protect me.” A campus visit shortly afterwards by the feminist author Robin Morgan was a further incitement to action, recalls Carol Tracy CGS’76 [“Safe Places,”Nov|Dec 2002].

Tracy, director of the Penn Women’s Center from 1977 to 1984, started her Penn career as a secretary and part-time night student. As president of Women for Equal Opportunity at the University of Pennsylvania (WEOUP), she was already, in her mid-20s, an experienced labor organizer and negotiator. So when Penn women decided to protest, she became one of the principal negotiators—along with Carroll Smith-Rosenberg, assistant professor of psychiatry and history and later a pioneering women’s studies scholar.

The April 1973 “Stop Rape” sit-in, as Tracy recounts it, was limited to women and civil in tone. She remembers the protestors sending a note to the dean of students, Alice F. Emerson, asking to reserve the auditorium in College Hall. “What’s this all about?” Emerson asked.

“And we said, ‘Sorry, we have a list of demands here, and we’re going to sit in until we get them.’ And then [the dean] said, ‘When you have a sit-in, you don’t reserve the room—you take it over.’ Smith-Rosenberg, in her inimitable style, replied, ‘As you know, women are overly socialized, so we did ask permission. But we are taking it over.’”

Most of the women’s demands seem modest in retrospect: better campus lighting, more emergency phones and security officers, expanded shuttle bus service and walking escorts, improved residential hall security, a female officer in the department of public safety to liaise with victims. Weber recalls her “personal favorite” as permission to bring dogs to class. “My dog Emma, whom I got at six weeks old that spring, had a complete college education as a result,” she says.

The biggest agenda items were a women’s center and a women’s studies program or department, the latter a project already under discussion at the time. After four days of negotiations Smith-Rosenberg told the Daily Pennsylvanian: “We got everything we wanted, plus more.”

In their 1973-74 annual report, the new Penn Women’s Center’s co-coordinators, Sharon Grossman and Emiko Tonooka, summarized a busy first year. In addition to referrals, counseling, and a focus on childcare, the center, then housed in Logan Hall (now Claudia Cohen Hall), offered workshops on carpentry as well as bicycle and auto maintenance and formed consciousness-raising groups. Not every initiative was a success. The report noted that a feminist organic garden cooperative “suffered … from the summer vacation schedules of women on campus and from the midnight skulker who keeps picking off the eggplants just before they’re ripe.”

The coordinators requested more support from the University and concluded with this feminist plaint and rallying cry: “Women at Penn have worked hard for the University and in return have gotten lower wages, less interesting work and fewer promotions than men. Women also usually have additional responsibilities at home and are made to feel guilty and inadequate if those responsibilities ever conflict with their jobs. These ills need to be rectified, and women, who for too long have been taught to accept second-class citizenship, need to be helped and encouraged to appreciate themselves and to demand that appreciation from others.”

Tracy, who earned a law degree from Temple University at night during her directorship, embodied that same activist spirit. “I felt it was my job to get fired, if necessary,” she says.

Despite the new security measures, sexual violence remained a problem on campus—in part because the call, so to speak, was coming from inside the house. A February 1983 incident following a raucous party at the Alpha Tau Omega fraternity became notorious. Tracy counseled the woman involved, who described a gang rape perpetrated by as many as eight men. When the story broke, it sparked a major Penn protest and made national news.

Tracy called out Penn President Sheldon Hackney Hon’93 for what she saw as an inadequate University response. The fraternity was sanctioned, but the young men—some of whom admitted to having sex with their inebriated schoolmate—were never charged. According to a Philadelphia Inquirer Sunday magazine article, they settled the matter privately with the University, agreeing to perform community service, complete readings, and participate in group discussions of their conduct.

Though no one tried to fire her, Tracy says she had expended her political capital on the issue. “You don’t criticize the [University] president in the Wall Street Journal and think you’re okay,” she says. She left the Women’s Center to practice law and, in 1990, became executive director of the Women’s Law Project in Philadelphia, a “dream job” she held until her retirement last year. Tracy continues to teach a Penn course, “Law and Social Policy on Sexuality and Reproduction.”

Elena DiLapi SW’77—known to all as “Ellie”—was the Women’s Center’s longest-serving director, at the helm from 1985 to 2006.

With a degree from New York’s Stony Brook University in Youth and Community Studies, she started out in youth advocacy. As director of the Women’s Health Concerns Committee, her focus turned to women’s rights. At Planned Parenthood she did sexuality training and worked on racial disparities in healthcare and “the intersection of race and gender” in post-secondary education counseling. She also taught at Penn’s School of Social Policy & Practice and practiced as a sex therapist. “I take great pride in being a social worker,” she says.

DiLapi’s tenure coincided with both an expansion of the legal understanding of sexual harassment and continuing concerns about sexual violence. One initiative she spearheaded was a 1988 national conference, Decisions and Directions: Ending Campus Violence. “The experts were the students, who were doing their own workshops,” DiLapi says. Around this time, a group called Students Together Against Acquaintance Rape (STAAR) formed to raise awareness of the problem.

Erica Strohl C’91, now a legal writing instructor at the Mitchell Hamline School of Law in St. Paul, Minnesota, was a member of the Penn Women’s Alliance, a peer health educator, and a STAAR cofounder. “As on all campuses, then and now, there were sexual assaults,” she says. “There were people that we knew that had been assaulted in fraternities and probably other places. At the time, it was not something that was talked about very much. We were on the leading edge of a groundswell. The more we talked about it, the more people came forward. We would always refer people to the Women’s Center as one place they could go.”

A history and women’s studies major, Strohl had first come to the Penn Women’s Center for a work-study job. “I was probably there every day, and it was constantly informing the work I was doing,” she says, “because I was in constant conversation with Ellie and Gloria [Gay SW’80 WMP’99, the center’s longtime associate director].”

DiLapi recounts a call she received from a US Senate Judiciary Committee staffer, who said: “The senators don’t understand this thing about date rape. Could you help us?” That was how Strohl and another Penn student came to testify before the committee, chaired by then Senator Joe Biden Hon’13. DiLapi suggests that Biden’s late son Joseph Robinette “Beau” Biden III C’91, a classmate of Strohl’s, might have helped inspire the call. The Violence Against Women Act, enacted in 1994, ultimately provided funds to address campus violence. “I believe that was a direct result of our students going and giving testimony,” DiLapi says.

The Women’s Center plunged into the political ferment of the time. “Some of our students organized six buses to Washington for one of the pro-choice marches—really activist stuff,” DiLapi says. She says she was keen “to make sure that we had an explicitly anti-racist Women’s Center.” On her watch, the center hosted as many as 20 affinity groups: for African American women and Latinas, Asians, the LGBTQ community, international students and scholars, and others.

DiLapi visualized the center as “a place where people can come and tell their stories, a safe space where women could just say, ‘This is my reality,’ whether it’s about struggling in school or waiting to get tenure or being harassed or not getting the attention of the faculty.”

Along with individual services, DiLapi says she knew “we needed to look at institutional structures because they influence the experience of each individual. If we understand the history of racism, oppressions, violence structurally embedded into our institution, that’s where we need to do the change. If you don’t find the problem at the right level, you’re never going to find the right solution.”

One longtime practical problem at Penn was the fraternity dominance of Locust Walk, with alcohol-fueled parties and what Strohl calls “bro culture.” The prospect of verbal and other harassment made it so unpleasant for women to traverse the Walk, DiLapi says, that they sometimes detoured into dimly lit, more dangerous parts of campus. Students responded to the issue with another sit-in.

As DiLapi recalls: “They went into Sheldon Hackney’s office and said, ‘The only safe place on campus is Sheldon Hackney’s office.’ And they sat in Sheldon Hackney’s office.’’ Hackney, as it happened, was away at the time. But Penn Provost Thomas Ehrlich was there, and the administration was listening.

In April 1990, Hackney appointed a committee to study the question of diversifying Locust Walk. DiLapi and Strohl were both members. A 1991 report, which Strohl and three others declined to sign, recommended only gradual and modest changes. “The committee’s vision of the Locust Walk of the future is a vision of inclusion, where the Walk is defined not by who is on it or who owns space,” the report said, “but rather by the manner in which the residents and functions of Locust Walk reflect the community of the University of Pennsylvania.”

It took five more years for the Women’s Center—badly in need of more room for its activities—to secure a prime spot on the Walk at the renovated Locust House, a space it now shares with the African-American Resource Center.

The Women’s Center was still at Houston Hall when Erme Maula Nu’97 made her first, fraught visit.

The child of Filipino immigrants, Maula grew up in South Carolina and was recruited to Penn’s nursing program. “Coming to Penn was a lot of culture shock on a lot of different levels,” she says. “I didn’t realize it was an Ivy League school till I got here. I didn’t fit in. I didn’t speak Tagalog, so I wasn’t Filipino enough. And I wasn’t white, so I wasn’t [considered] Southern.”

She felt “really lost a lot of the time freshman year, and I also came with a lot of trauma.” During high school, she had been the victim of a sexual assault. In her first year at Penn she barely escaped another by a classmate at Hill College House. By sophomore year she was “really struggling with what I realize now was PTSD,” as well as depression, academic frustrations, and exhaustion from holding down three jobs.

When she confided in a work-study supervisor, the woman told her: “Erme, you know you were raped.” She suggested that Maula find help at the Women’s Center. But when Maula walked into Houston Hall, she says, “nobody said hi to me, and I felt so out of place.” She left quickly and visited Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS), which offered her medication. In the end, she took a mid-semester leave of absence to get therapy closer to home.

When she returned to campus that fall, she had someone “literally walk me in” to the Women’s Center. The reception this time was much warmer. She remembers being told, “Here’s a safe space for you to be, you can come and do your work there, we have all these programs—and we have counseling.” She became a center regular, eventually winning Penn’s Alice Paul Award in recognition of her contributions to community and women’s health.

As a nursing graduate student at Penn, Maula continued her association with the Women’s Center, working on the 30th anniversary celebration. She never finished her doctorate, but today serves as a care coordination nurse for Philadelphia FIGHT Community Health Centers.

The Penn Women’s Center, Maula says, was “the one place I felt like people could hear me and see me and value me. I wasn’t necessarily out as a queer person when I started college. It wasn’t till I came back as a grad student that I really embraced that identity. The Women’s Center was really instrumental in creating that space.”

When Felicity “Litty” Paxton G’95 Gr’00 began a decade-long stint as director of the Women’s Center in 2008, “there were a couple of immediate priorities,” she says.

One involved hiring a staff member focused on violence prevention, someone who could build more collaborative relationships with the Penn Police and the Division of Public Safety’s Special Services. From those efforts, Paxton says, the Penn Violence Prevention program emerged.

“The other fairly explicit charge,” says Paxton, now associate dean for undergraduate studies at the Annenberg School for Communication, “was to open up the center to more users, to make it a place that more students would feel comfortable calling a second home. Penn can feel overwhelming. We wanted to make sure that the Women’s Center was a place that students who didn’t identify as flag-waving feminists, on the one hand, or as victims of some kind of explicit trauma or discrimination would still want to come hang out.”

It was Paxton who supervised the creation of the lactation room, garden, library, and kitchen. The center was still providing “options counseling” for survivors of sexual assault and others, but most counseling services were by then the province of CAPS (now part of Student Health and Counseling).

How badly does Penn still need a women’s center? The answer may depend on “what data points you follow,” Paxton suggests. “If you want to count women presidents at Penn, we are looking really good. If you want to count undergraduate numbers at Penn, we are looking great.”

But in the world outside the University, “we’ve seen some massive setbacks in women’s rights,” she says. The Supreme Court has overturned Roe v. Wade, “misogyny is alive and rising,” and women in government and business “are nowhere near parity,” she says. In sum, “there’s still a lot of work to do.”

But the nature of the Women’s Center, as well as its name, is up for debate. “The question moving forward is, what does it mean to be running a women’s center at a moment in history where many of our students are challenging the notion of a dual-sex world?” Paxton asks.

Sherisse Laud-Hammond SW’05 first used the Women’s Center when she was a graduate student living off campus in Cheltenham, outside Philadelphia. It was “a home away from home,” a place where she felt comfortable enough to take naps. When she became director in 2019, she smiled when she noticed others doing the same. “It was beautiful to see,” she says.

Laud-Hammond, now senior director of Penn Alumni Leadership and Inclusion, says she wanted the center to be “a safe and brave space for everyone,” not just people who identified as women. One focus under her leadership was wellness. Then the pandemic hit.

When the University shut down in March 2020, Laud-Hammond took the center’s programming virtual, often in concert with other Penn organizations, including the neighboring African-American Resource Center, the LGBT Center, and CAPS. Because the Women’s Center was known for its variety of loose-leaf teas, the center transitioned to “Tuesday Tea with PWC,” an online occasion to check in and experience community. Other programming included yoga and workshops on psychological and financial wellness. After the murder of George Floyd, the center and its partners offered “healing and solidarity circles” for Black staff and faculty.

“I hold multiple identities: I’m a woman, I’m Black, I’m a single mother raising a Black male child,” Laud-Hammond says. “This was a chance for me to be vulnerable. Now, after the pandemic, I feel like I can bring my full, authentic self to work. That’s one lesson I learned through some of the wellness workshops we had. That is what the Women’s Center did for many people throughout the pandemic: allowed people to show their vulnerability.”

“I had a lot of people lean on my shoulders. I leaned on a lot of other people’s shoulders. And I found a lot of those communities in the Women’s Center,” says Serena Martinez C’23, who identifies as nonbinary and uses they/them pronouns.

Martinez, a gender, sexuality, and women’s studies (GSWS) major at Penn, came out as nonbinary after an online fall 2020 class called Trans Method and was a board member of the Penn Association for Gender Equity, based at the Women’s Center. The group advocates for faculty training and gender-neutral bathrooms, among other causes. Martinez, who plans a career as a therapist specializing in gender and sexuality, wrote the manual for a new pre-orientation program, PennGenEq, for students interested in gender equity and social justice.

Martinez is also among those who favor changing the Women’s Center’s name. “We’re stuck in this weird place between history and the future,” Martinez says. “A lot of groups have been pushing for the name to be changed for a while.

“The most feasible option is Gender Center,” they continue. “It’s hard to take the center seriously when they say it’s for people of all genders when they’re called the Women’s Center. I’m not sure it really matters for cisgender men as much, but I know that trans people have felt excluded by that title in the past.”

Luke Godsey C’26, who identifies as “agender,” has heard similar sentiments from friends. But Godsey, who is bearded, masked, and enjoying the craft activity at the September open house, doesn’t feel the same. (Godsey, by the way, has no preferred pronouns. “Just call me Luke,” Godsey says.)

“I’ve been trying to tell people that the Women’s Center is for all genders,” says Godsey, who was introduced to the center by PennGenEq. The sophomore linguistics major now regularly studies, lunches, and procrastinates there. “At first, I was scared because of the name, but the second I got here everyone was super accepting,” Godsey says. “I actually like to stay here a lot and use the craft room upstairs because I like to quilt and crochet.”

Foster, the center’s associate director for six years before becoming director in January, presides over the controlled chaos of the open house with an easy charm. “It was quite a journey getting here,” she says. Raised in Willingboro, New Jersey, she holds undergraduate and graduate degrees from Villanova University. She has worked in communications, marketing, development, strategic planning, and mentoring women—all useful skills as she negotiates the conflicting needs and demands of the center and its constituencies.

Over time, says Foster, “there’s been a broadening of what it means to be a space that advocates for gender equity. There was a time when that meant cis-women. Now we’re being very intentional about making sure that we are supporting people of all gender identities. Trans and nonbinary members have their own unique challenges as people who experience marginalization. But we’re all in this fight together to counteract patriarchy.”

That includes male allies, Foster adds. “We want to make sure that men feel comfortable in this space as well,” she says. “It’s a very delicate balance.”

History may be on her side. “We have helped women and people of many identities through some of the most difficult times of their life,” says Laud-Hammond. “A university is not only for academics. It’s a place to grow in many ways. I am proud that the Women’s Center is still standing, and that it’s still creating that space.”

SIDEBAR

Changing Names, Broadening Focus, Continuing Challenges

Like the Women’s Center, the Penn Program in Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies is marking its 50th anniversary this academic year. GSWS will partner with its scholarly arm, the Center for Research in Feminist, Queer, and Transgender Studies, and the Penn Women’s Center to host a symposium from February 29 to March 2, 2024. The goal, according to its website, is “to celebrate 50 years of transformative scholarship and activism on Penn’s campus.”

According to Melissa E. Sanchez, director of both the GSWS program and the FQT Center, the anniversary discussion will also focus on the program’s continuing shortfalls in funding and structure. “For the last 50 years, we’ve been trying to become a department,” says Sanchez, the Donald T. Regan Professor of English and Comparative Literature.

GSWS offers both majors and minors. Required courses for the major include Gender & Society and Introduction to Queer Studies. An upgrade to departmental status would permit GSWS to hire its own faculty and develop more courses, as well as to compensate faculty for administrative work.

Sanchez calls the lack of departmental status “symptomatic of a more general institutional lack of support for the project,” but she does cite one encouraging development: “For the first time last year, the deans in Arts & Sciences allowed us to work with the advancement office seeking donors,” she says, “so we’re hoping that new relationship will allow us to generate more financial support, so we can grow.”

GSWS began as Women’s Studies, part of a nationwide trend. The first Women’s Studies department was established at San Diego State University in 1970.

“When I came [to Penn] in 2006,” says Sanchez, “we were still amidst something of a backlash against feminism and feminist studies. So, you would get a lot of students saying, [for instance,] ‘I’m not a feminist, but I just believe that women should have equal access to opening credit cards.’

“And that’s something that’s really changed,” she says. “I think people are very upfront about being feminists.” She credits recent social and political developments—including the MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements, the US Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe v. Wade, and “the right-wing attack on trans kids and trans adults”—for the evolution in attitudes. “A lot of that,” she says, “has made students who maybe 20 years ago felt more complacent realize how urgent rights for women and gender and sexual minorities continue to be.” Class enrollments have climbed as a result, Sanchez says.

In 2006, Women’s Studies was renamed Gender, Culture and Society. It adopted its current name four years later. “The renaming,” Sanchez says, “came out of decades of debate, not only at Penn, but within Women’s Studies more generally, about whether Women’s Studies was trans-exclusionary, queer-exclusionary, too focused on white middle-class women. There was a lot of debate about what the name would be.”

The FQT Center also has undergone a rebranding. It was established in 1984 as the Alice Paul Center for Research on Women, Gender and Sexuality, in honor of the Penn alumna and suffragist. Its executive board voted to rename it in 2021, in part to avoid what the website calls “a patriarchal elevation of the individual, charismatic leader over the many less celebrated persons working for change.” Paul’s problematic record on race also “seemed to be sending the wrong message on inclusivity,” Sanchez says. (An otherwise sympathetic account of Paul’s career [“The Serene Strategist,” May|Jun 2017], quotes a biographer’s view that her “failure to unreservedly welcome” Black participation in the 1913 suffrage march in Washington, DC “left a permanent stain on her reputation.”)

It’s a fair bet that as the field evolves, so, too, will the language defining it. “It’s entirely possible to me,” says Sanchez, “that by the time we’re celebrating the 100th anniversary [of GSWS] there will be another name, because of changes and conversations that we can’t possibly anticipate right now.” —JMK

Julia M. Klein is a frequent contributor to the Gazette.