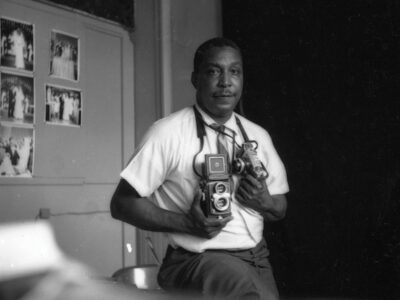

A husband-and-wife photography duo use their cameras to reveal the power of faces.

Imagine fleeing your country, with no time to pack. Your whole identity is tied up in a Ziploc bag. You board a rubber boat made for 20 people, crammed with twice that number of passengers, not knowing if your life vest is counterfeit. Will it keep you afloat should the boat capsize, or will it drag you down? Your journey is six hours under the scorching Mediterranean sun, and you haven’t eaten in days. There are children with what look like acid burns all over their bodies. A woman with a prosthetic leg. Two heavily pregnant women, traveling alone.

“What does it take for people to leave their home in those conditions to try to get somewhere?” asks Theresa Menders WG’94. “It must be pretty devastating to make those decisions.” Along with her husband, Daniel Farber Huang WG’94, she spent two weeks in 2017 and again in 2018 documenting the refugee camps at Souda and Vial on the island of Chios, Greece. They’ve taken and distributed over 2,000 portraits through the project they call the Power of Faces.

The United Nations calls the global refugee crisis “the greatest humanitarian crisis” since the end of World War II. More than 68.5 million people have been forced to flee their homes due to violence and persecution, a number roughly equivalent to the entire population of France. According to the UN Refugee Agency, the number of refugees and migrants in Greece alone stands at more than 75,000, including close to 15,000 on its islands.

They come to Europe from Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, South Sudan, Ethiopia, and other war-torn countries. They are looking for a better life for their families. “A lot of what we are trying to do is simply dispel fear about who or what a refugee is,” Huang says.

“[We want to show] people as a family, as individuals, as newlyweds,” adds Menders, explaining why they use brightly colored backdrops and intentionally crop out the camps.

“It’s really easy to take a picture of a person in a bad situation,” Huang says. “That’s pretty much what most refugee photos are.” But most viewers will dissociate from those kinds of scenes, he says, instead of connecting to the humanity in the subject’s eyes. “So we wanted to actually separate the environment from the individual.”

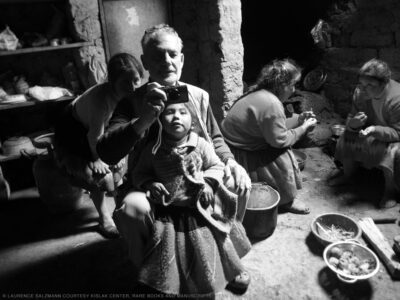

Huang and Menders gain access to the camps by partnering with NGOs, as a sort of volunteer marketing arm. In addition to documenting relief work, they set up a makeshift studio outside the group’s trailer and invite anyone to sit for a portrait.

They bring portable printers, photo paper, frames, and consent forms, along with their camera equipment. Sometimes they use generators; other times they can plug into the NGO’s electricity. “It’s a couple hundred pounds of stuff,” Huang says.

The fabric backdrops are chosen out of necessity, because they’re easy to fold. The flashy colors are intentional, though.

“When you put up a giant bright-orange backdrop, it’s going to draw attention,” Huang says. It also adds a sense of levity to a grim situation. Dozens of curious folks line up to see what’s going on. Women tidy their head scarves and put on make-up; children make the ‘peace’ sign; husbands kiss their wives. It is a fun and joyous, if arduous, process.

“They’re definitely hard, long, tough days,” says Huang, noting that they process several hundred prints per day. “But we go in knowing that they’re going to be.”

For a lot of people, the photos are validating. “It meant that somebody cared and that somebody in the outside world recognized that they were there, that they existed,” Menders explains. For others, the simple act of holding a family photo brings comfort. “In addition to losing all of their personal possessions, they also lost all of their family photos” when they fled their homelands, she says.

“And when that sank in, it was really powerful because suddenly there was a feeling of responsibility,” Menders continues.

Huang and Menders have taken their project to the TEDx stage twice; they presented on photojournalism at SXSW this year; they speak with high school groups and on college campuses; and they show their photos in various galleries, including pop-up exhibits with Amnesty International.

They are self-taught photographers who started formalizing their hobby after the September 11 attacks. Living in New York City at the time, they found that documenting recovery efforts was a way to understand the tragedy and “help us heal,” says Menders. Adds Huang, “Having a camera was, in a lot of ways, like having a security blanket.”

They took their photos of the recovery to various museums and historical societies, and “much to our surprise, a number of them actually asked if they could keep copies in their permanent collections,” Huang says. “It made us realize that a lot of what we had done had historical significance,” Menders says, “That was the beginning of thinking about how we could tell stories of other situations or other people through pictures.”

They started taking photos, with a focus on women’s and children’s issues and the alleviation of poverty, in the Republic of Vanuatu, Haiti, Colombia, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, India, China, and now Greece, where the Power of Faces project took root. The project continued in Tijuana, Mexico, where they traveled in December. In April, they made a trip to Bangladesh to take portraits at the Rohingya refugee camps.

“We’d like to do this full-time, but we both have day jobs,” says Menders, who now resides in Princeton, New Jersey, with Huang and their four children. She’s an IT director at a pharmaceutical company, and he’s the owner of a strategic advising firm.

“For the moment, we have a voice that we can use. And there are so many people we are meeting whose voices have been taken away from them,” Menders says. “There’s almost an obligation that we use our voices to raise awareness.” —NP