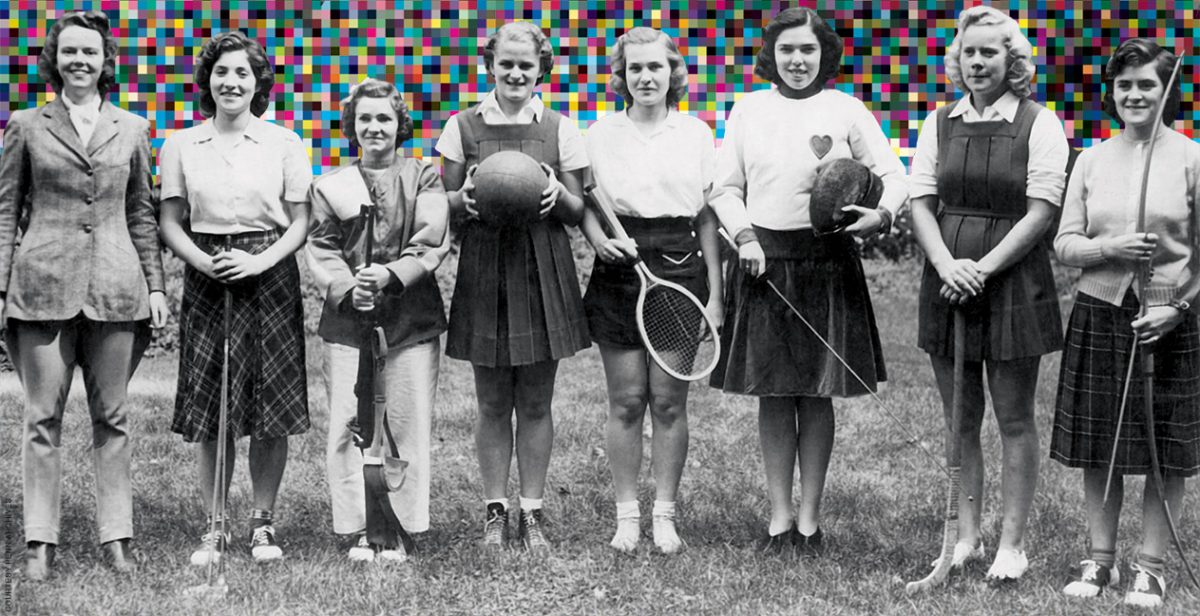

Photo courtesy Penn Archives

As the University celebrates 100 years of women’s sports, a handful of prominent former student-athletes recall their athletic triumphs and hurdles—and the paths they both followed and paved.

By Dave Zeitlin

Not long after the Penn men’s basketball team captured the 1920 national championship, members of the University’s newly formed women’s team were enjoying a different kind of hoops delight.

“The thrill of seeing our first printed basketball schedule still lingers—the sight of the Penn–Pitt game is not yet forgotten,” declares a page from the University’s 1922 women’s yearbook. “For who would imagine last year that we would be able to invite teams to come play us, as we did George Washington, Adelphi, and Pittsburgh? The first fine exaltation that we felt when we first saw those ‘Penn beat Pitt’ tags and knew they referred to us, still is with us.”

Few records exist from that 1921–22 season—the women’s basketball team’s first of intercollegiate competition—but the yearbook does boast of five victories, including its “big game” over the University of Pittsburgh. “Basketball is not all,” the yearbook continued. “Hiking, fencing, swimming—all our sports are flourishing.”

Photo courtesy Penn Archives

The groundwork for these achievements had been laid just one year earlier—and about 40 years after women began to earn degrees from the University—with the foundation of the Women’s Athletic Association. Led by physical education instructor Margaret Majer (who left Penn in 1924 to marry Olympic gold medalist John Kelly and whose future children would include Olympic rower Jack Kelly C’50 and the actress Grace Kelly), the association paved the way for the creation of several women’s teams and funding for new facilities.

A century later, the University’s Division of Recreation and Intercollegiate Athletics is honoring the 100th anniversary of the Women’s Athletic Association and the official start of women’s athletics at Penn. The celebration will include old photos, interviews, and video montages at pennathletics.com, as well as specially made patches on the uniforms of Penn’s 16 varsity women’s teams—some of which have risen to championship-level prominence.

But it hasn’t been an easy road to get there, and title aspirations haven’t always been possible. About five years after its founding, the Women’s Athletic Association shifted its focus from intercollegiate competition to intramural activity. And once it returned to intercollegiate play after about a decade, games were local and the stakes seemingly small. In the campus history series book University of Pennsylvania, a photo of the 1938 women’s basketball team accompanies a passage describing its season as four home games and two away games, including a quote from the 1939 women’s yearbook that explains “the inconvenience of out-of-town games was more than compensated by the graciousness of the opponent-hostesses who held teas for the Pennsylvania women after the game.”

Over the next few decades, women continued to fight for an athletic perch. Top athletes like Penn Athletics Hall of Famers Cynthia Johnson Crowley CW’52 (softball/basketball/badminton) and Penny Teaf Goulding CW’65 GEd’65 (field hockey/softball/basketball/lacrosse/badminton) played for multiple Penn teams, a stark contrast to the highly specialized nature of sports today.

It wasn’t until the 1970s—when Title IX of the federal Education Amendments of 1972 prohibited sex-based discrimination—that women’s sports began to more closely resemble the men’s game, with teams earning varsity status and joining Ivy League competition while records and statistics were maintained and preserved. But it took even longer for many women to be properly recognized for their athletic skills.

To paint a picture of some of these struggles and triumphs, we’ve spotlighted a handful of the University’s most prominent female athletes over the past half-century, spanning several different decades and sports, all of whom have pushed their programs forward—beginning with a “double All-American” who arrived on campus at a transformational time.

Olympic Ambitions

Photo courtesy Penn Archives

“The word may not yet have gone forth from Weightman Hall, but the Penn athlete who received the highest national recognition last year is a woman.”

So reads the opening paragraph of a feature story in the Gazette’s December 1972 issue titled “Meet Penn’s Double All-American.”

After describing some of Julie Staver CW’74 V’82’s feats in field hockey and lacrosse, the author Susie Adams CW’72 continues, with more than a hint of bemused bitterness: “Why are her achievements secret? Because, first of all, being a woman athlete at Penn is like being a teetotaler at a cocktail party; it’s unusual, gauche, but tolerable if kept quiet. It isn’t just that Penn alumni haven’t heard of Julie; unless they play on teams with her or sit beside her in a Russian lit course, even Penn students draw a blank when you mention the star in their midst.”

An All-American in field hockey (1973) and lacrosse (1973, 1974) who played on numerous US national field hockey and lacrosse teams throughout the 1970s and ’80s, Staver’s place in Penn Athletics lore is now secure. The Julie Staver Award, which Penn presents annually to the outstanding athlete who competes in both of her sports, has ensured that.

But Staver, now a veterinarian in Reading, Pennsylvania, doesn’t sugarcoat what her athletic experiences were like at the time. “I came to Penn when women’s athletics wasn’t very well supported,” she says. Whether that meant sharing uniforms, buying her own equipment, or playing games on Hill Field, “where sometimes you had to fight with the intramural guys to get off the field and out of the way,” it was a battle to simply get through a full (all-local, non-Ivy) schedule, let alone win games.

Of course, this wasn’t a problem exclusive to Penn. Growing up in rural central Pennsylvania, Staver played field hockey and basketball at Lower Dauphin High School because those were the only two sports offered for girls. It wasn’t until arriving at Penn—a school she chose because she wanted to be in a city—that she learned how to play lacrosse. “I kind of had a knack for it,” says Staver, who quickly got called in to play for the US national team.

Ivy League competition for field hockey and women’s lacrosse didn’t begin until 1979–80 (the first Ivy League championships in women’s sports were held before that, beginning with rowing in 1974) but Staver still detected changes from the time she arrived at Penn until she left. As a senior, she got the chance to take on future Ivy League rival Princeton for the first time, and to play games inside Franklin Field, which “was a big deal for us.” She also notes that “Title IX made a huge difference,” bringing better access to trainers, physical therapists, and full-time coaches. At Penn, Staver played under Ann Sage, a pioneering head coach at Penn who helped build both the field hockey and lacrosse programs, and then spent a couple of years as her assistant after graduation.

Staver also continued to play on the US national field hockey team after graduating (picking that over lacrosse because she couldn’t handle traveling for both) and even after starting at Penn’s School of Veterinary Medicine in 1978. She initially planned to hang up her cleats after the 1980 Summer Olympics, the first in which women’s field hockey was a sport. But after the US boycotted the Games, which she notes was “devastating for lots of people,” she decided to hang on for four more years, through her vet school graduation and the beginning of her career as a veterinarian.

Staver ended up serving as cocaptain of the US field hockey team at the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles, helping the Americans capture the bronze medal thanks to a unique ending. After finishing the round-robin tournament tied with Australia for third place in points and goal differential, the US team was called back out onto the field—from the stands, where the players had been wearing street clothes—to face Australia in a tie-breaking shootout, which the US won. “We thought we were out of it,” Staver says.

Staver isn’t the only Penn athlete to medal at the Olympics, which has a rich Olympic tradition for both men and women [“Penn in the Olympics,” Jul|Aug 2012]. One of her classmates, swimmer Elie Daniel CW’74, won gold, silver, and bronze at the 1968 Olympics before arriving at Penn—and then bronze in 1972. (A Gazette feature, from the May 1973 issue, paints a picture of another superstar athlete overlooked. “No school even approached me,” Daniel told the Gazette about her lack of recruitment. “I was a gold medal winner. Football players, they get wined and dined, and they’re a dime a dozen.”)

Even if there wasn’t always much fanfare, other women followed Daniel and Staver to the Olympics, including fencer Mary O’Neill C’86 and a slew of rowers from Anita DeFrantz L’77 to Susan Francia C’04 G’04 [“Gold, Again,” Sep|Oct 2012] to Regina Salmons C’18, who has been tapped to join Team USA this summer in Tokyo.

“There are always battles to be fought,” Staver says. “But it’s awesome to be a part of that history.”

Best of the Best

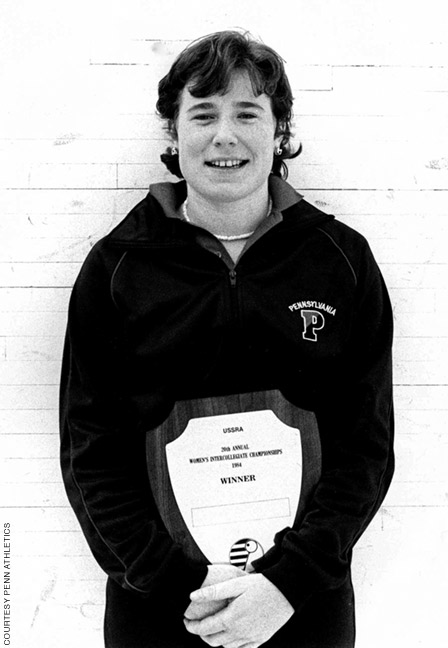

Photo courtesy Penn Athletics

Alicia McConnell C’85 enjoyed her own Olympic experiences, having worked as the director of training sites and community partnerships for the US Olympic Committee in Colorado. And she almost certainly would have reached the highest mountaintop as a competitor too … if only squash were an Olympic sport.

Nevertheless, McConnell is considered one of the greatest American squash players of all time, dominating the racket sport through the 1980s—before, during, and after her time at Penn.

“Around Weightman Hall, she has been called ‘the kind of player Penn gets once every 10 years,’ although Ann D. Wetzel, the women’s squash coach, considers it more like once in a lifetime,” reads a line from an old Gazette article, which also touted her ability to beat most men on the court, generally to their confusion. “Some guys think that it invalidates them as an athlete to have a woman better than they are,” McConnell told the Gazette while she was a Penn student. “But it doesn’t at all. They’re good the way they are, but I just happen to be better.”

Making her way in a man’s world was a theme for McConnell. Growing up in Brooklyn Heights, she recalls “going into the backdoors of men’s clubs” to play tennis and, when it rained, going inside to try out squash. “I just got hooked on squash,” McConnell recalls. “I could hit hundreds of balls in a row against the wall. Somehow my coaches convinced me that that was fun.” Crushing the ball, finding the right angles, wrong-footing her opponents—she loved it all.

A two-time national junior squash champion while in high school, McConnell decided to come to University City after playing in a tournament at Penn’s Ringe Courts, which, she notes, “had the best squash setup at the time.” Like Staver a decade earlier, McConnell also gravitated to lacrosse when she got to campus. Though she had never played the sport before, she not only made the Quakers’ varsity squad under Anne Sage but also rose to the US national team. She tried a little field hockey too, for a semester. “I just loved sports,” McConnell says. “If somebody gave me a chance to play, I was like, ‘OK. Why not?’”

But squash was her No. 1 sport, and she was No. 1 in squash. She won both the intercollegiate and national singles championships as a member of Penn’s varsity squash team, bringing home individual titles for the Quakers in 1982, 1983, and 1984. (Two other Penn women’s squash players would later wear the crown of national singles champion—Jessica DiMauro C’99 G’00 in 1996 and Reeham Salah EAS’19 in 2018.) McConnell would have gone for the clean sweep as a senior but lost her amateur status when she accepted prize money playing in squash tournaments in Europe after joining the US national lacrosse team on a UK tour. “We’re not talking a lot of money—maybe $500 here and there,” she says. But it helped pay her tuition, which she couldn’t otherwise afford. Even still, she needed a last-minute student loan to graduate on time. “It’s different today,” she says, bemoaning her struggles despite the attention she brought the University as the top squash player in the country. “I think female athletes now feel more empowered.”

Money continued to be an issue for McConnell after she graduated and went overseas, where there were more opportunities to find training partners and compete in tournaments. To make ends meet, she’d crash with friends, drive rather than fly when possible, and buy her own equipment. She rose to No. 14 in the world rankings, winning easily and often, but her travel expenses usually negated her earnings (about $18,000 in her best year, as she recalls). And without trainers and coaches to support her, the physical demands took a toll—so she quit the sport when she was still at the top of her game.

“Alicia McConnell used to dream of being the Billie Jean King of women’s squash and turning the sport into a multimillion-dollar enterprise,” opens an illuminating article written by Cindy Shmerler C’81 in the February 1, 1989, edition of the New York Times. “Now the seven-time national champion is quitting the game, disillusioned, disheartened, and, for the most part, broke.” The article ends with a quote from McConnell, who said: “It didn’t seem fair to me that here I was, number one, and still buying my own skirts. Over in Australia, everything is taken care of. … I feel used by squash. Through squash, I lost my whole identity.”

McConnell is more comfortable in her own skin these days. Long after struggling with her self-confidence at Penn while “becoming more aware of my sexuality,” and being “too afraid” to fully come out to all her teammates, she now lives in Dublin, Ireland, with her wife and their English bulldog and pug. She moved there about three years ago after wrapping up a 20-year run with the US Olympic Committee, which followed a stint in the 1990s teaching squash at the club where she first learned the game, the Heights Casino in Brooklyn.

She’s promoted squash everywhere she’s been, and while the sport is still not lucrative, she’s pleased to see American stars have a better chance at making a living at it than she did. She also likes—albeit with a pang of jealousy—that University City has become a hub for American squash with a new US center opening at Drexel and the Penn Squash Center recently undergoing $20 million renovations.

“It would’ve been fun to have a shot playing full time now,” admits McConnell, who serves on the Penn squash advisory board, heads Penn Alumni’s regional club in Ireland, and has mentored Penn athletes.

“But I just love seeing the growth of women’s sports,” she adds. “It’s a confidence booster for women to really appreciate what your body can do, what your mind can do. What’s most important is the friends you make, the life experiences you have, and the skills you learn through the sport. You don’t realize that when you’re playing—at least I didn’t.”

Never Stop Running (and Jumping)

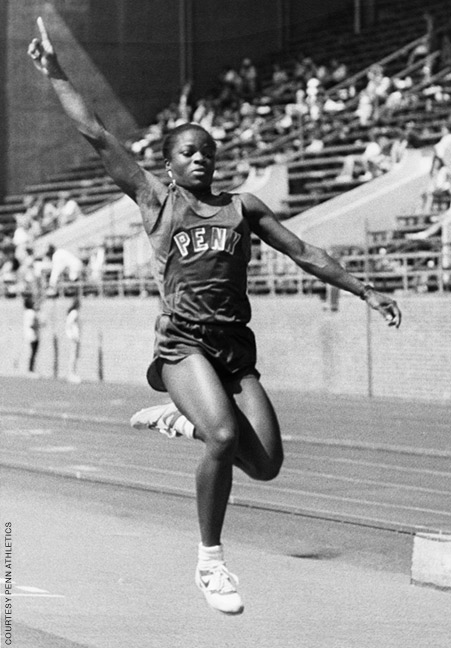

Photo courtesy Penn Athletics

Like Staver, McConnell, and other star athletes who came before her, Ruthlyn Greenfield-Webster Nu’92 had an opportunity to compete at the highest level after graduating. But hampered by a hamstring injury and ready to move on to a career in nursing, she turned down an invitation to jump at the 1992 US Olympic Trials for track and field.

“I decided I was done,” says Greenfield-Webster, who immediately began working as a nurse at NYU Langone, where she’s remained for the last 29 years. “I said to myself, I’ve done everything I can. I’m leaving on top of everything. Ivy champion. School record holder. Captain of my team. I’m good.”

A four-time Heptagonal Games champion in the triple jump who graduated with program records in that event for both indoor and outdoor track and field, Greenfield-Webster certainly left behind a strong legacy at her alma mater.

But, as it turned out, she wasn’t done.

About 15 years after graduating, she heard about Masters track and field for athletes over 35 years old. Intrigued, she started hopping, skipping, and jumping in her Yonkers, New York, backyard—and, from there, to Italy, Finland, France, Brazil, and other countries where the biggest Masters events were held.

Reinvigorated by an opportunity that wasn’t always available to women of a previous era, she added more medals to her collection, earning the trifecta she set out for as a national champion, regional champion, and world champion. But it didn’t come easy.

At the 2013 World Masters Athletic Championships in Brazil, she won gold in the women’s triple jump for her age group (40–44), despite competing with a meniscus tear in her right knee. At the 2019 North, Central America and Caribbean Region of World Masters Athletic Championships in Canada, she brought home triple jump gold in the next age bracket (45–49)—after sustaining a left foot plantar fasciitis injury that knocked her out of the 100-meter and 200-meter dash events, and other Team USA sprint relays.

“I’m crazy,” she laughs. “You would think it would make me stop, right? But, no. It really sort of motivates me more.” It’s gotten to the point, she says, where she actually gets worried when she’s not hurt. “I’m so used to competing with injuries that it doesn’t really faze me like it probably should—because I’ve been doing it since college.”

She credits her Penn coaches, Betty Costanza and Tony Tenisci, for helping her push through a hamstring injury to successfully defend her Heps/Ivy League triple jump title and develop her raw talent. Sometimes, that included tough love and a little bit of yelling, but “I love those two like they gave birth to me,” Greenfield-Webster says, noting they still support her in her Masters endeavors. “It’s a lifelong thing for me.”

She also has a lifelong connection to her alma mater, feeling a particular affinity for Franklin Field, where she’s competed at the Penn Relays from high school events to 40-and-older Masters relays. “I talk about Penn like you think I owned the place,” she says. She currently serves on the Penn track alumni board, conducts Penn Alumni interviews, and was named the 2018 Friar of the Year. A painting of her jumping adorns the lobby wall inside Penn Nursing’s Claire M. Fagin Hall, she says. “Can I tell you how amazing that feels to me?”

Greenfield-Webster is particularly proud of her nursing degree. When she first got to Penn, she recalls hearing that many nursing students drop out of the track program because it’s too time-consuming to balance both. “For me,” she says, “it was like, Challenge accepted.” She later learned that she was the first Penn track and field record holder to graduate from the nursing school.

But she wouldn’t be the last. Nia Akins Nu’20 GNu’20 recently graduated as one of the top runners in Penn history—and arguably one of the best women athletes the University has ever seen in 100 years. The school record holder in the 800 meters and the 1,500 meters and a two-time national runner-up in the 800, Akins helped bring the women’s track and field program to new heights with several overall team wins at the Heptagonal Championships and its first-ever distance medley relay championship at Penn Relays [“Penn Relays at 125,” Jul|Aug 2019]. And like Greenfield-Webster, Akins is Black. Last summer she wrote about race and an experience she had with racism for Runner’s World (which was later republished by Penn Nursing magazine). Now a professional runner, Akins has her sights set on the Olympics. “I absolutely adore Nia,” Greenfield-Webster says. “She has a special place in my heart.”

Getting the opportunity to see Akins—or any other Penn alum—in the Olympics would be quite the thrill for Greenfield-Webster, who has no plans to stop traveling the world to run and jump herself. COVID-19, of course, enforced a pause as she dealt with the far more serious implications of a once-in-a-century global pandemic. “For the first time in my career,” the New York nurse says, “this was something that actually scared me.” She also devoted extra time to supporting and comforting her two daughters, including one who missed her graduation, prom, and other teenage rites of passage as a 2020 Yonkers High School graduate.

But she managed to still train the entire time, and after turning 50 this year, is primed to dominate another age group (50–54). How long can she keep going from there? “The way these knees are acting up, I don’t know if I’m gonna make it to 90,” she says. “But I’m gonna try.”

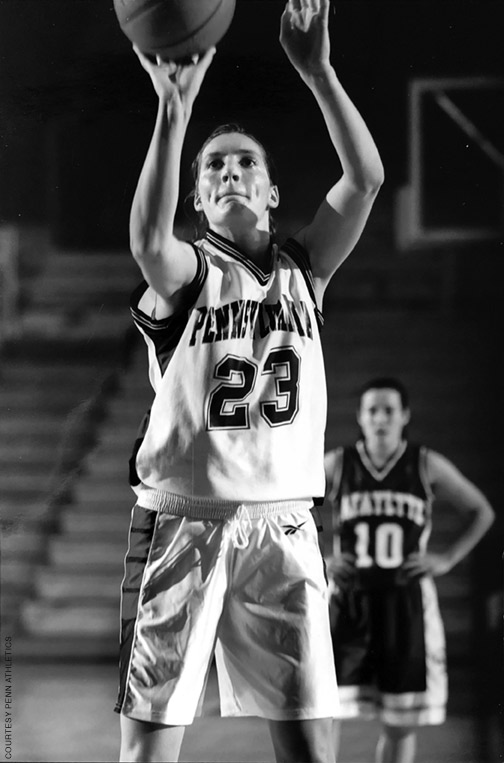

Palestra Lifer

Although basketball has the deepest roots of any of the Penn women’s athletic programs, it wasn’t until the turn of the millennium that it reached the next level.

And that was because of Diana Caramanico W’01 LPS’11.

The only men’s or women’s player in Penn basketball history to score more than 2,000 career points, she currently holds the Penn, Big 5, and Ivy League records for most career points with 2,415. She also holds Penn records for career rebounds (1,207), and steals (201), among other all-time marks, and was named the Ivy League Player of the Year three straight seasons.

And she capped it all off in 2001 by leading the Quakers to their first-ever Ivy championship and NCAA tournament berth, completing a stunning turnaround from when she arrived on campus with nine other freshmen recruits. Not surprisingly, the young and inexperienced team was picked to finish dead last in the Ivies. “But we had all come from winning programs,” Caramanico says. “No one told us we were supposed to lose.”

In her freshman year, the Quakers finished a respectable 13–13 overall and 8–6 in the Ivy League, good enough to come in fourth place. The next season, they finished third. As a junior in 1999–2000, Caramanico and the Quakers began to take off, winning 18 total games under the leadership of first-year head coach Kelly Greenberg, who had replaced Julie Soriero and implemented an up-tempo style that suited the 6-foot-2 Caramanico’s ability to run the floor.

Heading into her final season with a smaller group of classmates but still a strong class that included Erin Ladley C’01 (who would join Caramanico in the 1,000-point club), Penn had all the pieces to make a run. Caramanico remained confident even after the team lost five of its first six games. What followed was 21 straight victories, many of them memorable for different reasons.

The beginning of the streak included a win over Air Force that was played in an almost empty Palestra due to a snowstorm. About a week later, Caramanico scored 42 points against Albany, which remains a program single-game record. In a narrow come-from-behind win over Yale, Greenberg was ejected for arguing with the refs. In another nail-biter, Caramanico recalls former men’s basketball star Mike Jordan C’00 “herding hundreds of shrieking kids down under the basket to bother” a Dartmouth player shooting potentially game-winning free throws with no time left on the clock. She missed one, allowing Penn to run away with the win in overtime.

The Quakers ended up clinching the Ivy title with a few games left in the season but saw their long-awaited celebration curtailed because Harvard had “hid anything we could stand on to cut down the nets,” Caramanico recalls. They made up for it with a home win over rival Princeton to cap off a perfect Ivy season and roll into the NCAA tournament with an NCAA-best 21 game winning streak.

The Quakers flew to Lubbock, Texas, to take on Texas Tech in front of approximately 14,000 hostile fans—a long way from the “out-of-town” games around the Philadelphia area in the 1930s when tea was served afterwards. They lost, by a wide margin, 100–57, but the experience on the national stage was eye opening and formative for both Caramanico and the Penn program.

Caramanico went on to play professional basketball in France from 2001–2003, and actually played Texas Tech in an exhibition just a few months after the NCAA tournament. Even more surprising, Texas Tech fans who made the trip to France recognized her (despite the lack of any programs or rosters in the arena) and began a “Let’s Go Penn!” chant. “I almost started crying right there on the court,” says Caramanico, who was missing home at the time. “It was just what I needed.”

Almost 20 years since her basketball career ended, Caramanico is back home and “living the dream,” having built a life in Ardmore, Pennsylvania, with her husband Geoff Owens C’01, a former men’s basketball center she met in college, and their two athletic children, ages 12 and 9. And she’s far more recognizable at the Palestra, where she’s a regular visitor, than in any French gym. “That’s like my second home,” she says. “Our kids have known for years you don’t wear orange [Princeton colors] at the Palestra, and you try to avoid orange in general.”

She also believes her Penn education helped her navigate a few career changes, from playing basketball professionally and trying out for the WNBA … to working in international sales for AND1 … to starting a business on mental toughness training for athletes … to now teaching at her alma mater, Germantown Academy.

Penn, she notes, “set me up for success for the rest of my life.” Likewise, Caramanico helped set Penn women’s basketball up for success, elevating the standard so that Ivy titles became more regular and star players followed the legacy she carved. Three years after she graduated, one of her former teammates and fellow Penn Athletics Hall of Famer, Jewel Clark C’04, led the Quakers back to the NCAA tournament. More recently, Alyssa Baron C’14, Sydney Stipanovich C’17, Michelle Nwokedi C’18, Eleah Parker C’21, and Kayla Padilla W’23 have grabbed the torch and helped turn Penn into a perennial Ivy League powerhouse.

Yet the University’s marquee program, in many ways, is the same one that used to pluck players from other Penn teams even if they had never before played the sport … and now has legitimate national championship aspirations every year.

New Frontiers

Photo courtesy Penn Athletics

Perhaps the best way to chart the growth of women’s sports over the last 100 years is through lacrosse—and, more specifically, through Ali DeLuca (now Cloherty) C’10.

Like Caramanico a decade earlier, DeLuca joined a program that did not have a championship tradition. But by the time she left, Penn had not only ascended to the top of the Ivy League but advanced all the way to the national semifinals three times, including one trip to the national championship game.

“I wanted to be a part of the story,” DeLuca says. “And every woman on that team at the time felt the same way. We would always joke because in 2007 they kept referring to us as this Cinderella story. And we did not think of ourselves like that.”

DeLuca credits Karin Brower Corbett, the team’s head coach since 2000, for being “the foundation of that shift” and instilling in her players a mindset that “we were an elite team that deserved to be amongst what people considered the top teams in the country.” The Quakers hadn’t qualified for the NCAA tournament since 1984 or won the Ivy League since 1982 when they did both in 2007, soaring to a No. 2 ranking in the country before losing to Northwestern in the final four.

Penn got a measure of revenge against Northwestern—which won five straight national titles from 2005 to 2009—by upsetting the Wildcats during the 2008 regular season. But that ’08 campaign once again ended with a loss to Northwestern, this time in the national title game. So close to reaching the pinnacle of college sports, it would be the most difficult defeat of DeLuca’s career. “It’s still hard now to even take that loss,” she says, although a double overtime defeat to Northwestern in the 2009 semifinals, on a “totally lucky” goal, was almost as excruciating.

The Quakers fell one win short of four straight trips to the final four in 2010, but accomplished something perhaps even more remarkable by capping off its fourth straight sweep of the Ivy League—an achievement that would have been unimaginable in previous years and decades. “When I came here, the Princetons and Dartmouths were killing us,” Brower Corbett told the Gazette in 2007. “It was, ‘Can we hang with them for 20 minutes?’ These girls were not recruited by those programs, and they didn’t believe they could beat them.”

For Penn to move so swiftly from Ivy also-ran to Ivy powerhouse—and remain on that perch to this day with 11 league titles since 2007—is something DeLuca wears like a badge of honor. “When I talk to people who know Ivy League athletics, they’re stunned,” she says of her spotless 28-0 record against conference foes. “No one does that. It’s incredible.” Among the former Ivy athletes she talks to about it is her husband, former Brown football player Colin Cloherty. They live in Silver Spring, Maryland, with their two toddler sons who are usually holding a ball or a stick. (Her two sisters also went to Brown, where they played lacrosse. “Brown’s a great place but Penn’s obviously better,” she says.) She also likes to bring it up with her former teammates, many of whom she’s remained close with. She says she is consistently impressed by where they’ve gone in their careers since graduating. “We’re sort of used to winning,” says DeLuca, who works for National Geographic’s CreativeWorks. “Being super competitive and strong-willed translates professionally after you’re done with lacrosse.”

Just the same, some of DeLuca’s fondest lacrosse memories include dance parties in the locker room before games, and the entire team chanting “Giant Chicken” to get pumped up—and no one knowing exactly why. “To an outsider looking in,” she says, “it was probably like the weirdest and craziest thing.”

Several of DeLuca’s teammates earned major accolades at Penn, including All-American nods for goalkeeper Sarah Waxman C’08 (also a two-time National Goalkeeper of the Year and a recent Penn Athletics Hall of Fame inductee) and Melissa Lehman C’08 (who went on to keep winning titles as a longtime Penn assistant coach). But DeLuca—who still holds the program record for career goals with 148—became the first player in school history to be a finalist for the Tewaaraton Award, given annually to the best lacrosse player in the country.

She didn’t win it but believes a Penn women’s lacrosse player will hoist that trophy eventually. She’s equally confident in Brower Corbett’s ability to navigate the unique challenges of two straight lost pandemic seasons and lead the Quakers back to the final four—and beyond.

“There’s no doubt in my mind,” she says, “that we’ll win the national championship one day.”

From field hockey to track to soccer, softball, squash, and more, other Penn programs keep raising the bar too. And as they move into a new century, the dreams will remain tantalizing, the goals never greater—a 100-year climb from feeling like nobody was paying attention to trying to make sure nobody can look away.

As a holder of three pre-Title 9 letters in 1955, I wince when I

remember how it was. There was no travel beyond the fringes of Philadelphia. There was no trainer. No special perks. Not much practice time. No summer program. No fans.

And, yes, thanks to the pill and to Title 9 and to the very idea of gender equality, we continue to do better but it was an awfully long time coming, wasn’t it?